5.2: Hinduism + Buddhism

- Page ID

- 67048

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Hinduism + Buddhism

Buddhism developed in reaction to the established religion in India at the time—Hinduism.

6th century B.C.E. - present

Hinduism and Buddhism, an introduction

Origins of Hinduism

Unlike Christianity or Buddhism, Hinduism did not develop from the teachings of a single founder. Moreover, it has diverse traditions, owing to its long history and continued development over the course of more than 3000 years. The term Hindu originally referred to those living on the other side of the Indus River, and by the thirteenth century it simply referred to those living in India. It was only in the eighteenth century that the term Hindu became specifically related to an Indic religion generally.

Hindus adhere to the principles of the Vedas, which are a body of Sanskritic texts that date as early as 1700 B.C.E. However, unlike the Christian or Islamic traditions, which have the Bible and the Koran, Hinduism does not adhere to a single text. The lack of a single text, among other things, also makes Hinduism a difficult religion to define.

Hinduism is neither monotheistic nor is it polytheistic. Hinduism’s emphasis on the universal spirit, or Brahman, allows for the existence of a pantheon of divinities while remaining devoted to a particular god. It is for this reason that some scholars have referred to Hinduism as a henotheistic religion (the belief in and worship of a single god while accepting the existence or possible existence of other deities). Hinduism can also be described as a religion that appreciates orthopraxy—or right praxis. Because doctrinal views vary so widely among Hindus, there is no norm based on orthodoxy or right belief. By contrast, ritualized acts are consistent among differing Hindu groups.

Hindu gods and worship of the gods

Within the Hindu pantheon are a number of gods, goddesses and deities; however, one entity is supreme, Brahman. Brahman is the Supreme Being; the One self-existent power; the Reality which is the source of all being and all knowing. Enlightenment for the Hindu is recognizing that all things are united.

Brahman is traditionally said to manifest on earth as the Trimutri: Brahma as the creator god; Vishnu, the preserver; and Shiva, the destroyer. Brahman manifests himself on earth in other gods so that he will be more knowable. With this said, for Hindus, reaching salvation is understanding that everything is in union. The different names and forms that a god can take is immaterial as they are essentially Brahman.

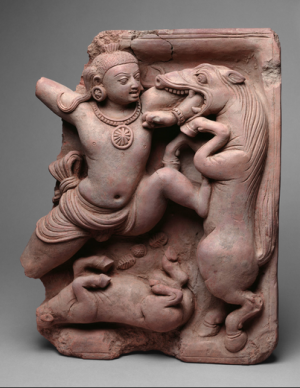

However, as human beings we crave the protection of many gods, in particular those gods with a very specific power. Beyond the Trimutri are numerous Hindu gods and goddesses: Ganesha, the elephant headed god and Durga, the female warrior. Each god has a specific power and role. Ganesha, for example, is the lord of beginnings and the remover of obstacles. It is for this reason that images of Ganesha are present in Hindu temples, regardless of who the temple is dedicated to. Durga, who is solicited for protection, is also equally sought by women for fertility.

These personal deities are called ishtadeva. Having an ishtadeva does not mean a worshipper forsakes other gods, but it does mean that they have a more personal relationship with their patron deity.

Hindu Worship

For Hindu worshipers, the concept of bhakti is important. Bhakti is the devotion, honor and love one has for god. The physical actions, which one takes to express one’s bhakti can be done in a number of ways such as through darshan and puja.

Darshan means auspicious sight. By making a pilgrimage to see a god at a temple or shrine, the practitioner is going there specifically to take darshan. It should be noted that for Hindus the image of a god is not just a symbol or a portrait of their god, but is in fact an embodiment of that god. While the god does not always reside in the image, he or she does, from time to time, descend to earth and takes the form of the image. Often these times coincide with special holidays or certain times of the day—especially when rituals in honor of the gods are taking place. It is during these times, when the god is present, that darshan is most effective. To worship the god, the practitioner must be seen by the god and in turn the practitioner must see the god.

The importance of sight and its reciprocation in worship is directly reflected in the production of Hindu images. Images of gods have large eyes, so that it is easier for them to see the practitioner and for the practitioner to make eye-contact with them. Moreover, there exists a strict set of parameters artisans must follow in order to create images of gods so that gods and goddesses will inhabit the body. Gods will not inhabit forms that they do not consider worthy of their stature. This set of rules is based on mathematical proportions and is called iconometry. Therefore, in order for an image to be successful it needs to have the appropriate iconography (forms and symbols) associated with the god and also have appropriate iconometry.

Beyond darshan, worship for a Hindu includes puja or offerings as a form of honoring. One can make puja by lustrating an image with ghee, milk or oils, or simply adorn an image with garlands of flowers.

The Hindu world

For Hindus, time and space are organized and conceived of as cyclical—where one era cycles into the next. In Hindu mythology there are cycles of cosmic ages from a golden age (kitri yuga) to the dark age (kali yuga). We are currently in a degenerate dark age. When it ends, in several millennia, the universe will be destroyed and Brahma will create it anew. Just as the universe and time is conceived as being cyclical so is the progress of the individual soul. For Hindus, the soul is bound to the samsaric wheel. Samsara is the continuous cycle of birth, death and rebirth.

In order to escape this cycle one must realize everything is one, everything is Brahman. In other words, one’s individual soul is the same as the universal soul. When this is accomplished it is called moksa and marks the end of the samsaric cycle of rebirth.

All of this is understood through Hindu Dharma. For the Hindus, Dharma explains why things are and why they should be—there must be order in everything including society. And this is where the idea of the caste system finds credence in Hinduism. One’s ranking in the social caste system is dependent on ones karma, translated from the Sanskrit to mean “act/ion.” For Hindus, karma originally began as a purely ritual act, which was the act of making sacrifice/offerings to the sacred fire/gods. For Hindus, it is the Brahmin, or the priestly class, who has access to the sacred fire, which directly corresponded to their social rank, which was at the top. Brahmins refers to an elite caste, which includes priests, scholars, teachers, etc.

Buddhism and the Buddha

The social caste system as described by Hindu Dharma was likely one of the biggest factors in the development of Buddhism. Buddhism developed in reaction to the established religion in India at the time—Hinduism (Brahminism). Buddhism, in contrast to Hinduism, has a single founder and while there is no singular text there are texts that outline the teachings of the Buddha as the great and exemplary teacher.

Buddhism was founded by one individual, Siddhartha Gautama, sometime in 6th or 5th century B.C.E. Prince Siddhartha Gautama’s biography has very much become a part of the foundation of the Buddhist teachings.

Prince Siddhartha Gautama lived a cloistered life of ease and abundance. At the age of 29 years he came across a sick man, an old man, a dead man and an ascetic. Siddhartha had never seen these unpleasant aspects of life before, and was profoundly moved and confused. He could no longer ignore the existence of suffering in the world and live his life of privilege, knowing that old age and death are our inevitable fate. It was at this time that he chose to depart from his sheltered life to become an ascetic and find the truth to the universe.

The middle way

He removed his jewels and rich robes forever, cut his hair and went into the forest and became an ascetic where he studied with a variety of sages and yogis, but he was unsatisfied with their teachings. He also practiced several types of self-mortification—most importantly starvation, because he wanted to concentrate exclusively on his spiritual advancements. These searches proved fruitless and he finally came to the realization that the Middle Path (avoiding extremes) was the path towards enlightenment. The middle path teaches adherents to avoid extremes. For Siddhartha that meant neither a life of luxury as a prince nor starving himself.

He traveled to a town in northern India called Bodh Gaya, where he sat under a type of tree called a bodhi tree and vowed to remain there until he reached enlightenment. After remaining in that spot in deep meditation for 49 days, he was tested one night by the demon god, Mara (a symbol of ignorance—he is not evil, just deluded). Mara tried to disrupt Siddhartha’s meditation and sent his beautiful daughters to tempt him. Siddhartha remained unmoved, kept his meditation and thus passed this final trial and gained enlightenment. At the moment of his enlightenment, he came to be known as Buddha, which translates from Sanskrit as “enlightened one.”

The Buddha’s teachings utilized much of the same vocabulary of the Hindus. For example, Dharma for Hindus explains why things are and why they should be. For Buddhists, Dharma came to be defined as the teachings of the Buddha. The caste system became invalid as the Buddha simply denied its relevance towards reaching salvation—as his salvation denied the existence of the self.

For Hindus, salvation comes in realizing that everything is one, everything is in union with Brahman and one’s soul is the same as the universal soul. When the Buddha taught that there was no self, there was no need to attach the self to Brahman. Similarly, in the Hindu context karma refers to ritual action—darshan and puja—whereas for the Buddhists karma has always been an ethical action. For Buddhists, karma (action)—whether good or bad —lay in the intention. Buddha deemphasized Brahmanical rituals by making karma an ethical act and focusing on intention. Moreover, the Brahmin caste who had direct access to the gods through rituals were no longer a privileged class in Buddhism. In Buddhism, anyone who understood the teachings of the Buddha could achieve salvation.

For Buddhists, salvation is gained through the understanding of the ways things really are according to the Buddha’s Dharma. Once an individual has become enlightened they can then reach a state of nirvana. Nirvana is described as the extinguishment of suffering by escaping the continuous cycle of rebirth called samsara. An individual’s ability to reach enlightenment and nirvana are dependent on their understanding of the Dharma. Recall that the goal for both Hindus and Buddhists is to escape the samsaric cycle of rebirth—but each religion’s interpretation of how to do this and what it meant to get off the cycle differed.

The Buddha’s teachings

The basic tenets of the Buddhist faith are called the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. The Four Noble Truths are meant to uncover one’s eyes of the dust from the secular world and show the practitioner that:

- Life is suffering: it is suffering because we are not perfect nor is the world in which we live perfect.

- The origin of suffering is attachment or desire: attachment to transient things and ignorance thereof. Objects of attachment also include the idea of a “self” which is a delusion, because there is no abiding self. What we call “self” is just an imagined entity, and we are merely a part of the ceaseless becoming of the universe.

- The cessation of suffering can be attained through detachment of desire and craving.

- The end of suffering is achieved by seeking the middle path. It is the middle way between the two extremes of excessive self-indulgence and excessive self-mortification, leading to the end of the cycle of rebirth.

The middle path can be achieved by following the Eightfold Path to end suffering and begin the course to reaching nirvana. The Eightfold Path requires the practitioner to seek:

- Right or Perfect View: is the beginning and the end of the path, it simply means to see and to understand things as they really are and to realize the Four Noble Truths.

- Right Intention: can be described as a commitment to ethical and mental self-improvement.

- Right Speech: is abstaining from the use of false, slanderous and harmful words which hurt others.

- Right Action: means to abstain from harming others, abstaining from taking what is not given to you and to avoid sexual misconduct.

- Right livelihood: means that one should earn one’s living in a righteous way and that wealth should be gained legally and peacefully.

- Right Effort: is the prerequisite for the other principles of the path as one needs the will to act or else nothing will be achieved.

- Right Mindfulness: the ability to contemplate actively ones’ mind, body and soul.

- Right Concentration: the ability to focus on right thoughts and actions through meditation.

Buddhist practice

During the time of the Buddha, there was only one school of Buddhism, which is the one that the Buddha taught; however, over time there came to be different sects of Buddhism. These Buddhist sects were produced by fissures within the monastic order. Such fissures occur in differences in practice not in belief in the doctrine. In other words, regardless of what sect of Buddhism one is talking about, all adhere to the Buddha’s doctrine of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. Two major schools of Buddhist thought are Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism.

Theravada Buddhism

Theravada translates to “the School of the Elders” since it is believed by some to be closer to the Buddha’s original teachings. According to Theravada Buddhists, each person is responsible for their own enlightenment. There are teachers and models, and the Buddha is exemplary, but, everyone must ultimately reach enlightenment by their own volition. Today, Theravada Buddhism is practiced in much of mainland Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka.

Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism was a school that developed in c. 100 C.E. Mahayana literally means: the “big vehicle.” It is a big vehicle that transports more sentient beings off the samsaric cycle towards enlightenment and nirvana. One of the cornerstones of Mahayana Buddhism is compassion, which is visualized in the appearance of bodhisattvas. Bodhisattvas are altruistic enlightened beings that vow to delay their own parinirvana (final nirvana) until every sentient being reaches enlightenment. Mahayana Buddhism is most commonly practiced in East Asia and Vietnam.

Differences

Where Theravada and Mahayana differ is that Mahayana regards becoming a bodhisattva as the ultimate goal. Therefore depictions of bodhisattvas are frequent in Mahayana art. Another fundamental difference between the two schools is how they regard the character of the Buddha. Mahayana considers the Buddha to be nearly divine in nature—he is superhuman and as such, he is worshipped in Mahayana Buddhism.

Theravada considers the Buddha an exemplar, the great teacher.

Decline of Buddhism in India

By the thirteenth century Buddhism had largely disappeared from the country of its birth, though it has been kept alive in various forms across Asia. In fact, it is the single most important shared cultural phenomenon found throughout Asia was the transmission and adoption of Buddhism.

Beliefs made visible: Hindu art in South Asia

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Video from the Asian Art Museum.

Introduction to Buddhism

Buddhisms

When we talk about the religion that worships the Buddha, we refer to it as singular: Buddhism. However, it may be more accurate to talk about “Buddhisms.” The religion that originated in India took on so many different forms and adapted in such a variety ways that it is often difficult to see how the various sects of Buddhism are related. What do they all have in common? The worship of the Buddha, of course! But who was Buddha? Was Buddha a man or a god? In early forms of Buddhism, Buddha is most definitely a man. As the religion changes and adapts, the Buddha is deified.

Origins

Buddhism originated in what is today modern India, where it grew into an organized religion practiced by monks, nuns, and lay people. Its beliefs were written down forming a large canon. Buddhist images were also devised to be worshiped in sacred spaces. From India, Buddhism spread throughout Asia.

In order to appreciate the magnitude of the Buddha’s achievement, we should try to imagine what life was like in early India, particularly in towns and villages of the Ganges River Valley—like Kapilavastu in the foothills of the Himalayan mountains—in what is now the country of Nepal. This is the area in which the Buddha was likely born, in about 560 B.C.E. Every year the river flooded the valley destroying crops. Monsoons came every year too, creating famine. There were also severe droughts and disease such as dysentery and cholera.

The Brahmanas (the Hindu priests) chanted the Vedic hymns (the oldest scriptures of Hinduism) and offered fire sacrifices to Brahma (the Hindu god of creation). However, they did not improve conditions for the common man. From the earliest times, Hindu society was stratified. Castes were firmly established in the economy with the Brahmanas the creators and perpetuators of a social order highly favorable to themselves.

The Middle Way

One of the Buddha’s greatest spiritual accomplishments was the doctrine of the Middle Way. He discovered the doctrine of the Middle Way only after he lived as an ascetic for some time. This experience convinced him that one should shun extremes. One should avoid the pursuit of worldly desires on the one hand and severe, ascetic discipline on the other. Despite his doubts about existing religious practices, and his strong sense of mission, he did not think of himself as the creator of a new religion. Rather, he felt the need to purify the religion of his day.

Buddha took for granted the truth of cosmological perspectives indigenous to the Indus valley—the worldview that is often associated with Hindu conceptions. One must understand what time and space look like in the Buddhist framework of ancient India. This framework was shared by all, whether one was an adherent of Brahmanism, Jainism, or Buddhism.

Samsara and Time

Samsara (a Sanskrit word) literally means a “round” or a “cycle.” In the ancient Indian worldview this means the endless cycle of rebirth and death—there is no beginning and no end. This endless cycle is governed by karma (causality).

In ancient India, time is measured in kalpa. There is an unending cycle of Destruction, Rubble, Renovation, and Duration. Each period is 20 kalpa long and they are thought of as a circle.

Destruction: Has a great beginning, but gets progressively worse. There are scourges of fire, water, wind.

Rubble: Space is dark and empty, only wind exists in this stage, with seeds of karma.

Renovation: This is the phase when things build up from the bottom.

4. Earth 3. Metal 2. Water 1. Wind

Whirling wind forms a disk of water. Impurities float to the top and form a disk of metal. This disk breaks down and forms the earth.

Duration: This is the phase of preservation, and at the end of this phase, sentient beings appear.

Space

Mount Sumeru (or Meru) is the cosmic axis—that is, the link between heaven and earth. The Mountain is the center of the world in this cosmological conception, both physically and in terms of importance. On top of Mount Sumeru are the palaces of the Gods. Mount Sumeru is surrounded by seven chains of mountains and an ocean that has four continents: North = rectangle; West = circle; South = trapezoid (Jambudvipa, where humans live); East = crescent moon.

The Universe is vertically structured. At the top is the realm of “no form.” This realm has no qualities that can be perceived by the senses. It is impossible to have a conception of it. Next are the realms of form that can be perceived in various states of meditation. One can see pleasant sights, bright light, and perceive coolness.

Below is the realm of desire. This realm has six levels. This is our realm. The six levels are the six paths of rebirth. The highest realm is that of the gods (deva). Halfway between gods and humans are demi-gods (asura). Humans and animals dwell on the surface of Jambudvipa. Hungry ghosts inhabit the shadow world below the animals. This level has much pain and suffering. Beings here are always hungry and never satiated. Hell beings occupy the lowest level. There are 8 levels within this level. At the eighth and lowest level there is no rest between tortures.

Karma

How do people (beings) move about in this world? The answer is karma. Karma is the law that regulates all life in samsara. Existence in time and space is ruled by karma. Karma means action or deed. Every action has a result. Every deed has an effect. Karma is a built-in universe scale for good and evil—good leads to good result and vice versa. Karma governs the long-term and the short-term. Karma is never destroyed. In the short term good deeds lead to a good result and bad deeds lead to a bad result. Karma transgresses from one life to another. It determines how a being will be reborn (higher or lower). Karma is not predestination because the concept of predestination does not take into account free will. Your current circumstances are determined by deed in your previous life, but between the present and the future there is free will. Upward mobility is possible.

What are the implications of the Buddhist world view? Being reborn a human is rare and important—rare especially in the time of Buddha. Buddha is born only in a small time period within the phase of destruction. We are fortunate to have access to his teachings since there is limited time and place to be given the chance to encounter Buddha. A being can only encounter Buddha and benefit in the human realm.

Nirvana

How does one achieve salvation? All is impermanent. All is cyclical. All is painful. Even Gods suffer. They are only gods for one lifetime and then they are reborn lower down. Also Gods do not have access to Buddha. Beings need to find a way out of the endless cycle of rebirth. The goal is Nirvana. Nirvana is extinction. Nirvana is the traditional name for that which is not samsara. Where is Nirvana? Nowhere. Nirvana is outside the vertical concept of the universe.

Beliefs made visible: Buddhist art in South Asia

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Video from the Asian Art Museum.

The historical Buddha

A human endeavor

Among the founders of the world’s major religions, the Buddha was the only teacher who did not claim to be other than an ordinary human being. Other teachers were either God or directly inspired by God. The Buddha was simply a human being and he claimed no inspiration from any God or external power. He attributed all his realization, attainments and achievements to human endeavor and human intelligence. A man and only a man can become a Buddha. Every man has within himself the potential of becoming a Buddha if he so wills it and works at it. Nevertheless, the Buddha was such a perfect human that he came to be regarded in popular religion as super-human.

Man’s position, according to Buddhism, is supreme. Man is his own master and there is no higher being or power that sits in judgment over his destiny. If the Buddha is to be called a “savior” at all, it is only in the sense that he discovered and showed the path to liberation, to Nirvana, the path we are invited to follow ourselves.

It is with this principle of individual responsibility that the Buddha offers freedom to his disciples. This freedom of thought is unique in the history of religion and is necessary because, according to the Buddha, man’s emancipation depends on his own realization of Truth, and not on the benevolent grace of a God or any external power as a reward for his obedient behavior.

Life of the Buddha

The main events of the Buddha’s life are well known. He was born Siddhartha Gautama of the Shaka clan. He is said to have had a miraculous birth, precocious childhood, and a princely upbringing. He married and had a son.

He encountered an old man, a sick man, a corpse, and a religious ascetic. He became aware of suffering and became convinced that his mission was to seek liberation for himself and others. He renounced his princely life, spent six years studying doctrines and undergoing yogic austerities. He then gave up ascetic practices for normal life. He spent seven weeks in the shade of a Bodhi tree until, finally, one night toward dawn, enlightenment came. Then he preached sermons and embarked on missionary travels for 45 years. He affected the lives of thousands—high and low. At the age of 80 he experienced his parinirvana—extinction itself.

This is the most basic outline of his life and mission. The literature inspired by the Buddha’s story is as various as those who have told it in the last 2500 years. To the first of his followers, and the tradition associated with Theravada Buddhism and figures like the great Emperor Ashoka, the Buddha was a man, not a God. He was a teacher, not a savior. To this day the Theravada tradition prevails in parts of India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Thailand.

To those who, a few hundred years later, formed the Mahayana School, Buddha was a savior and often a God—a God concerned with man’s sorrows above all else. The Mahayana form of Buddhism is in Tibet, Mongolia, Vietnam, Korea, China, and Japan. The historical Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama) is also known as Shakyamuni.

The stupa

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Video from the Asian Art Museum

Can a mound of dirt represent the Buddha, the path to Enlightenment, a mountain and the universe all at the same time? It can if its a stupa. The stupa (“stupa” is Sanskrit for heap) is an important form of Buddhist architecture, though it predates Buddhism. It is generally considered to be a sepulchral monument—a place of burial or a receptacle for religious objects. At its simplest, a stupa is a dirt burial mound faced with stone. In Buddhism, the earliest stupas contained portions of the Buddha’s ashes, and as a result, the stupa began to be associated with the body of the Buddha. Adding the Buddha’s ashes to the mound of dirt activated it with the energy of the Buddha himself.

Early stupas

Before Buddhism, great teachers were buried in mounds. Some were cremated, but sometimes they were buried in a seated, meditative position. The mound of earth covered them up. Thus, the domed shape of the stupa came to represent a person seated in meditation much as the Buddha was when he achieved Enlightenment and knowledge of the Four Noble Truths. The base of the stupa represents his crossed legs as he sat in a meditative pose (called padmasana or the lotus position). The middle portion is the Buddha’s body and the top of the mound, where a pole rises from the apex surrounded by a small fence, represents his head. Before images of the human Buddha were created, reliefs often depicted practitioners demonstrating devotion to a stupa.

The ashes of the Buddha were buried in stupas built at locations associated with important events in the Buddha’s life including Lumbini (where he was born), Bodh Gaya (where he achieved Enlightenment), Deer Park at Sarnath (where he preached his first sermon sharing the Four Noble Truths (also called the dharma or the law), and Kushingara (where he died). The choice of these sites and others were based on both real and legendary events.

“Calm and glad”

According to legend, King Ashoka, who was the first king to embrace Buddhism (he ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent from c. 269 – 232 B.C.E.), created 84,000 stupas and divided the Buddha’s ashes among them all. While this is an exaggeration (and the stupas were built by Ashoka some 250 years after the Buddha’s death), it is clear that Ashoka was responsible for building many stupas all over northern India and the other territories under the Mauryan Dynasty in areas now known as Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.

One of Ashoka’s goals was to provide new converts with the tools to help with their new faith. In this, Ashoka was following the directions of the Buddha who, prior to his death (parinirvana), directed that stupas should be erected in places other than those associated with key moments of his life so that “the hearts of many shall be made calm and glad.” Ashoka also built stupas in regions where the people might have difficulty reaching the stupas that contained the Buddha’s ashes.

Karmic benefits

The practice of building stupas spread with the Buddhist doctrine to Nepal and Tibet, Bhutan, Thailand, Burma, China and even the United States where large Buddhist communities are centered. While stupas have changed in form over the years, their function remains essentially unchanged. Stupas remind the Buddhist practitioner of the Buddha and his teachings almost 2,500 years after his death.

For Buddhists, building stupas also has karmic benefits. Karma, a key component in both Hinduism and Buddhism, is the energy generated by a person’s actions and the ethical consequences of those actions. Karma affects a person’s next existence or re-birth. For example, in the Avadana Sutra ten merits of building a stupa are outlined. One states that if a practitioner builds a stupa he or she will not be reborn in a remote location and will not suffer from extreme poverty. As a result, a vast number of stupas dot the countryside in Tibet (where they are called chorten) and in Burma (chedi).

The journey to enlightenment

Buddhists visit stupas to perform rituals that help them to achieve one of the most important goals of Buddhism: to understand the Buddha’s teachings, known as the Four Noble Truths (also known as the dharma and the law) so when they die they cease to be caught up in samsara, the endless cycle of birth and death.

The Four Noble Truths:

life is suffering (suffering=rebirth)

the cause of suffering is desire

the cause of desire must be overcome

when desire is overcome, there is no more suffering (suffering=rebirth)

Once individuals come to fully understand The Four Noble Truths, they are able to achieve Enlightenment, or the complete knowledge of the dharma. In fact, Buddha means “the Enlightened One” and it is the knowledge that the Buddha gained on his way to achieving Enlightenment that Buddhist practitioners seek on their own journey toward Enlightenment.

The circle or wheel

One of the early sutras (a collection of sayings attributed to the Buddha forming a religious text) records that the Buddha gave specific directions regarding the appropriate method of honoring his remains (the Maha-parinibbāna sutra): his ashes were to be buried in a stupa at the crossing of the mythical four great roads (the four directions of space), the unmoving hub of the wheel, the place of Enlightenment.

If one thinks of the stupa as a circle or wheel, the unmoving center symbolizes Enlightenment. Likewise, the practitioner achieves stillness and peace when the Buddhist dharma is fully understood. Many stupas are placed on a square base, and the four sides represent the four directions, north, south, east and west. Each side often has a gate in the center, which allows the practitioner to enter from any side. The gates are called torana. Each gate also represents the four great life events of the Buddha: East (Buddha’s birth), South (Enlightenment), West (First Sermon where he preached his teachings or dharma), and North (Nirvana). The gates are turned at right angles to the axis mundi to indicate movement in the manner of the arms of a svastika, a directional symbol that, in Sanskrit, means “to be good” (“su” means good or auspicious and “asti” means to be). The torana are directional gates guiding the practitioner in the correct direction on the correct path to Enlightenment, the understanding of the Four Noble Truths.

A microcosm of the universe

At the top of stupa is a yasti, or spire, which symbolizes the axis mundi (a line through the earth’s center around which the universe is thought to revolve). The yasti is surrounded by a harmika, a gate or fence, and is topped by chattras (umbrella-like objects symbolizing royalty and protection).

The stupa makes visible something that is so large as to be unimaginable. The axis symbolizes the center of the cosmos partitioning the world into six directions: north, south, east, west, the nadir and the zenith. This central axis, the axis mundi, is echoed in the same axis that bisects the human body. In this manner, the human body also functions as a microcosm of the universe. The spinal column is the axis that bisects Mt. Meru (the sacred mountain at the center of the Buddhist world) and around which the world pivots. The aim of the practitioner is to climb the mountain of one’s own mind, ascending stage by stage through the planes of increasing levels of Enlightenment.

Circumambulation

The practitioner does not enter the stupa, it is a solid object. Instead, the practitioner circumambulates (walks around) it as a meditational practice focusing on the Buddha’s teachings. This movement suggests the endless cycle of rebirth (samsara) and the spokes of the Eightfold Path (eight guidelines that assist the practitioner) that leads to knowledge of the Four Noble Truths and into the center of the unmoving hub of the wheel, Enlightenment. This walking meditation at a stupa enables the practitioner to visualize Enlightenment as the movement from the perimeter of the stupa to the unmoving hub at the center marked by the yasti.

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\)

The video above shows the perspective of someone circumambulating the Mahastupa in Sanchi, the soundtrack plays monks chanting Buddhist prayers, an aid in meditation. Circumambulation is also a part of other faiths. For example, Muslims circle the Kaaba in Mecca and cathedrals in the West such at Notre Dame in Paris include a semicircular ambulatory (a hall that wraps around the back of the choir, around the altar).

The practitioner can walk to circumambulate the stupa or move around it through a series of prostrations (a movement that brings the practitioner’s body down low to the ground in a position of submission). An energetic and circular movement around the stupa raises the body’s temperature. Practitioners do this to mimic the heat of the fire that cremated the Buddha’s body, a process that burned away the bonds of self-hood and attachment to the mundane or ordinary world. Attachments to the earthly realm are considered obstacles in the path toward Enlightenment. Circumambulation is not veneration for the relics themselves—a distinction sometime lost on novice practitioners. The Buddha did not want to be revered as a god, but wanted his ashes in the stupas to serve as a reminder of the Four Noble Truths.

Votive Offerings

Small stupas can function as votive offerings (objects that serve as the focal point for acts of devotion). In order to gain merit, to improve one’s karma, individuals could sponsor the casting of a votive stupa. Indian and Tibetan stupas typically have inscriptions that state that the stupa was made “so that all beings may attain Enlightenment.” Votive stupas can be consecrated and used in home altars or utilized in monastic shrines. Since they are small, they can be easily transported; votive stupas, along with small statues of the Buddha and other Buddhist deities, were carried across Nepal, over the Himalayas and into Tibet, helping to spread Buddhist doctrine. Votive stupas are often carved from stone or caste in bronze. The bronze stupas can also serve as a reliquary and ashes of important teachers can be encased inside.

This stupa clearly shows the link between the form of the stupa and the body of the Buddha. The Buddha is represented at his moment of Enlightenment, when he received the knowledge of the Four Noble Truths (the dharma or law). He is making the earth touching gesture (bhumisparsamudra) and is seated in padmasan, the lotus position. He is seated in a gateway signifying a sacred space that recalls the gates on each side of monumental stupas.

Additional resources

The Stupa from the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco

Buddhist monasteries

Why Monasteries?

So what is a monastery exactly? A monastery is a community of men or women (monks or nuns), who have chosen to withdraw from society, forming a new community devoted to religious practice. The word monk comes from the Greek word monos, which means alone.

It can be difficult to focus a lot of time on prayers and religious ritual when time needs to be spent on everyday activities that insure one’s survival (such as food and shelter). Think of the ancient Sumerian Votive Statues from Tell Asmar, for example. These statues were placed in a temple high above the village. Each statue represented an individual in continual prayer as a stand-in for the actual individual who was busy living, tending to crops, cooking food, and raising children. The person was depicted with hands clasped in prayer (at the heart center) with eyes wide open in perpetual engagement with the gods.

The work of the monastery

In Buddhism and Christianity however, instead of statues, monks or nuns pray on behalf of the people. The monastery typically becomes the spiritual focus of the nearest town or village. In Christianity the monks pray for the salvation of the souls of the living. But in Buddhism, there is no concept of the soul. The goal is not heaven, rather it is cessation from the endless cycle of rebirth (samsara), to achieve moksha, which is freedom or release from attachment to ego or the material world and an end to samsara, and to realize nirvana (or liberation), which is to be released into the infinite state of oneness with everything.

The Four Noble Truths or Dharma

It is difficult to achieve moksha, which is why the Buddha’s teaching focuses on achieving Enlightenment or knowledge that helps the practitioner. This is described succinctly in his Four Noble Truths, also referred to as the dharma (the law):

Life is suffering (suffering = rebirth)

The cause of suffering is desire

The cause of desire must be overcome

When desire is overcome, there is no more suffering (suffering = rebirth)

Adept practitioners of Buddhism understood that not everyone was ready to perform the necessary rites to obtain the ultimate goals of ending samsara (rebirth). The common person could, however, improve their karma (an action or deed that enacts a cycle of cause and effect) by everyday charitable acts that were mostly directed toward the monastic community.

The Buddhist monks and nuns meditated and prayed on behalf of the lay community (or laity—basically everyone who is not a priest or monk), those without specialized knowledge of the faith, assisting them in the goal of realizing The Four Noble Truths. Monks and nuns also instructed the lay practitioner on how to conduct the rituals, how to meditate, and advised them about which Buddhist deity to focus on (this depended on the issue or obstacle in the practitioner’s path to Enlightenment). The laity, in turn, supported the monks with donations of food and other necessary items. It was a mutually beneficial relationship.

The beginnings of monasteries

In the early years of Buddhism, following the practices of contemporary religions such as Hinduism and Jainism (and other faiths that no longer exist), monks dedicated themselves to an ascetic life (a practice of self-denial particular to the pursuit of religious or spiritual goals) wandering the country with no permanent living quarters. They were fed, clothed, and housed in inclement weather by people wishing to gain merit, which is a spiritual credit earned through virtuous acts. Eventually monastic complexes were created for the monks close enough to a town in order to receive alms or charity from the villagers, but far enough away so as not to be disturbed during meditation.

Three types of architecture: stupa, vihara and the chaitya

Buddhism, the first Indian religion to require large communal and monastic spaces, inspired three types of architecture.

The first was the stupa, a significant object in Buddhist art and architecture. On a very basic level it is a burial mound for the Buddha. The original stupas contained the Buddha’s ashes. Relics are objects associated with an esteemed person, including that person’s bones (or ashes in the case of the Buddha), or things the person used or had worn. The veneration, or respect, for relics is prevalent in many religious faiths, particularly in Christianity. By the time the Buddhist monasteries gained importance, the stupas were empty of these relics and simply became symbols of the Buddha and the Buddhist ideology.

Second was the construction of the vihara, a Buddhist monastery that also contained a residence hall for the monks.

Third was the chaitya, an assembly hall that contained a stupa (though one empty of relics). This became an important feature for the monasteries that were cut into cliffs in central India. The central hall of the chaitya was arranged to allow for circumambulation of the stupa.

The stupa is at the end of the nave (the main central aisle), as seen in the photo above. On either side of the columns are side aisles to help people walk through the space—around to the stupa, and back out. This is similar to the architecture of Early Christianity (for example, the side aisles at the Early Christian Church in Rome, Santa Sabina, which help the flow of people who come to worship at the altar at the end of the nave).

Buddhist Monasteries in India

In India, by the 1st century, many monasteries were founded as learning centers on sites already associated with Buddha and Buddhism. These sites include Lumbini where the Buddha was born, Bodh Gaya where he achieved enlightenment and the knowledge of the dharma (the Four Noble Truths), Sarnath (Deer Park) where he preached his first sermon sharing the dharma, and Kushingara where he died.

Ashoka: the first King to embrace Buddhism

Sites special to King Ashoka (304–232 B.C.E.), the first king (of northern India) to embrace Buddhism, were also integral to the building of monasteries. For example, the complex at Sanchi, where the original Great Stupa (Mahastupa) of Sanchi was created as a reliquary for the Buddha’s ashes after his death, became the largest of many stupas that were created later when a monastery was built at the site. Ashoka added one of his famous pillars at this location—pillars that not only proclaimed his acceptance of Buddhism, but also served as instructional objects on Buddhist ideology.

Between 120 BCE and 200 C.E. over 1000 viharas (a monastery with residence hall for the monks), and chaityas (a stupa monument hall), were established along ancient and prosperous trade routes. The monasteries required large living areas.

A vihara was a dwelling of one or two stories, fronted by a pillared veranda. The monks’ or nuns’ cells were arranged around a central meeting hall as in the plan of the Ajanta vihara (left). Each cell contained a stone bed, a pillow and a niche for a lamp.

The monastery quickly became important and had a three-fold purpose: as a residence for monks, as a center for religious work (on behalf of the laity) and as a center for Buddhist learning. During Ashoka’s reign in the 3rd century B.C.E., the Mahabodhi Temple (the Great Temple of Enlightenment where Buddha achieved his knowledge of the dharma—the Four Noble Truths) was built in Bodh Gaya, currently in the Indian state of Bihar in northern India. It contained a monastery and shrine. In order to acknowledge the exact site where the Buddha attained Enlightenment, Ashoka built a diamond throne (vajrasana – literally diamond seat) underscoring the indestructible path of the dharma.

Rock-cut caves

The rock-cut caves were established in the 3rd century B.C.E. in the western Deccan Plateau, which makes up most of the southern portion of India. The earliest rock-cut monastic centers include the Bhaja Caves, the Karle Caves and the Ajanta Caves.

The objects found in the caves suggest a profitable relationship existed between the monks and wealthy traders. The Bhaja caves were located on a major trade route from the Arabian Sea eastward toward the Deccan region linking north and south India. Merchants, wealthy from the trade between the Roman Empire and southeast Asia, often sponsored architectural additions including pillars, arches, reliefs and façades to the caves. Buddhist monks, serving as missionaries, often accompanied traders throughout India, up into Nepal and Tibet, spreading the dharma as they travelled.

Bhaja

At Bhaja there are no representations of the Buddha other than the stupa since Bhaja was an active monastery during the earliest phase of Buddhism, Hinayana (lesser vehicle), when no images of the Buddha were created. In Hinayana, the memory of the historical Buddha and his teachings were still a very real part of the practice. The Buddha himself did not encourage worship of him (something images would encourage), but desired that the practitioner focus on the dharma (the law, the Four Noble Truths).

The main chaitya hall (which contained a memorial stupa, empty of relics, above) at Bhaja contains a solid stone stupa in the nave flanked by two side aisles. It is the earliest example of this type of rock-cut cave and closely resembles the wooden structures that preceded it. The columns slope inwards, which would have been necessary in the early wooden structures in the north of India in order to support the outward thrust from the top of the vault. In similar stone caves, sometimes the columns are placed in stone pots, which mimic the stone pots the wooden columns were positioned in, in order to thwart termites. This is an example of a practical architectural practice being adopted as the standard.

Ajanta

At Ajanta, the earliest phase of construction also belongs to the Hinayana (lesser vehicle) phase of Buddhism (in which no human image of the Buddha was created). The caves are very similar to those at Bhaja. During the second phase of construction, Buddhism was in the Mahayana (greater vehicle) phase and images of the Buddha, predominantly drawn from the jataka stories—the life stories of the Buddha—were painted throughout. In Mahayana, which was more distant in time from the life of the Buddha, there was a need for physical reminders of the Buddha and his teachings. Thus images of the Buddha performing his Enlightenment and his first sermon (when he shared the Four Noble Truths with the laity) proliferated. The paintings at Ajanta provide some of the earliest and finest examples of Buddhist painting from the period. The images also provide documentation of contemporary events and social custom under Gupta reign (320-550 C.E.).

Rock-cut monasteries become more complex

Eventually, the rock-cut monasteries became quite complex. They consisted of several stories with inner courtyards and veranda. Some facades had reliefs, images projecting from the stone, of the Buddha and other deities. A stupa was still placed in the central hall, but now an image of the Buddha was carved into it, underscoring that the Buddha is the stupa. Stories from the Buddha’s life were also, at times, added to the interior in both paintings and reliefs.

Additional resources:

The art of Buddhism from the Freer | Sackler

Images of enlightenment: aniconic vs. iconic depictions of the Buddha in India

Depicting the divine

Representing divine figures has long been a thorny issue. After all, depicting the divine in human form would seem to define and limit the divine in a manner which seems to contradict the idea of God as infinite and all-powerful. There’s also the fourth commandment, as offered in the Hebrew Bible, which reads:

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. (Exodus 20:1-17)

While this commandment has been interpreted in various ways, Judaism and Islam both prohibit the representation of God and other divine figures in human form. Christianity has long relied on images of God, Christ, and the saints as a way of educating the public, but even so, at several points in history, images of divine figures were destroyed—often violently (the destruction of images is called “iconoclasm”). The earliest images of the Buddha also appear to avoid depicting him in human form, though scholars are still debating why this is the case.

Buddha, enlightenment and the Bodhi tree

The man who became known as the Buddha was a Hindu prince, named Siddhartha Gautama, who was born in the 5th or 6th century B.C.E. to a royal family—the leaders of the Shakya clan—living in what is now Nepal. When he was about 29 years old, Prince Siddhartha (who was also known as Shakyamuni) traveled outside of his sheltered palace and encountered an old man, a sick man, and a corpse—figures that, for the prince, epitomized the pain and suffering of the world. He also encountered an ascetic, someone who has chosen to abstain from the pleasures of life in order to pursue spiritual knowledge. After this experience, Prince Siddhartha decided to renounce his luxurious, royal life and to travel around the countryside as an ascetic, meditating and studying. Ultimately, Prince Siddhartha was seeking an end to worldly pain and suffering, and a release from the cycle of rebirth and death (samsara) that characterizes Hindu concepts of time (more on Hinduism and Buddhism here).

One of the most important moments in the story of Prince Siddhartha is when he reached spiritual enlightenment—a state of infinite knowledge—and became known as the Buddha or “the enlightened one.” This occurred about six years after the prince renounced his royal life, while he was meditating underneath a fig tree outside a small village in the present-day state of Bihar, India. The fig tree under which the Buddha reached enlightenment became known as the Bodhi (“awakened” or “enlightened”) tree, and the place where the Buddha sat became an important tirtha or sacred place known as Bodh Gaya (“awakened” or “enlightened” place).

Early images of the Buddha at Bharhut

Some of the earliest depictions of the Buddha reaching enlightenment appear as sculptural friezes on the exterior of sacred Buddhist monuments known as stupas, which Buddhist monks and nuns built as part of their monastic complexes (more on stupas here).

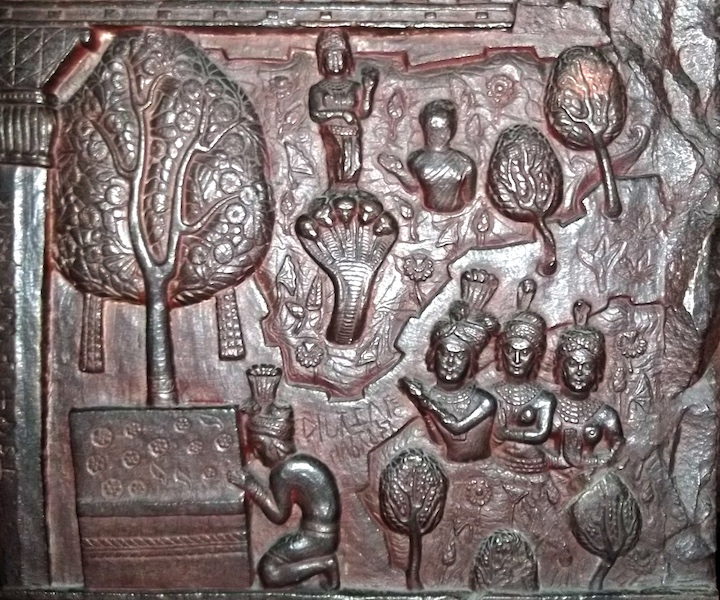

One such depiction is originally from the stupa at Bharhut in the present-day state of Madhya Pradesh, India (left). Carved in reddish-brown sandstone sometime around 80-100 B.C.E. this depiction appears on a railing (vedika) pillar that once surrounded the main stupa. The scene shows several figures kneeling and standing on an architectural form that encircles a large tree.

The place of enlightenment or the moment of enlightenment?

An inscription that accompanies this scene, carved into the roof of the architectural form, identifies it as “the Bodhi tree of holy Shakyamuni” [1] which has led some scholars to interpret this depiction as the location, or the tirtha, where the Buddha’s enlightenment took place—the tree under which Prince Siddhartha reached enlightenment and the temple that devotees later constructed at this sacred site.

Some of the figures in the scene appear kneeling in prayer in front of an altar at the base of the tree. Celestial beings fly near the top of the tree, and appear to toss flower garlands on the branches. Their presence reinforces the sacrality of the site.

On the right side of the relief, we see a pillar topped with an elephant capital, which, scholars argue, supports the interpretation of this scene as the site of enlightenment. This pillar recalls those constructed by Emperor Ashoka—one of the first Buddhist rulers in India—who erected pillars with animal capitals at important sites of the Buddha’s life (below, left).

In this interpretation, the Bharhut scene could be a depiction of pilgrimage—the kneeling devotees could be Buddhist practitioners traveling to Bodh Gaya as part of religious devotion, to visit the site where the Buddha reached enlightenment hundreds of years before.

However, some scholars argue that it is not simply the location (tirtha) of the Buddha’s enlightenment depicted in this scene, but rather the actual moment of enlightenment itself—complete with an aniconic, symbolic representation of the Buddha. (What does aniconic mean?)

In this interpretation of the scene on the pillar from Bharhut, the Buddha appears not in human form—but rather symbolically, represented by the altar. What we are seeing here is a representation of the Buddha’s formless state upon reaching spiritual enlightenment. In fact, some believe the inscription translates as “enlightenment of the Holy One Shakyamuni”[2] rather than the “Bodhi tree of holy Shakyamuni”—a reading that supports the interpretation of this scene as a depiction of the event of enlightenment not simply the place where enlightenment happened.

Other aniconic images of the Buddha

Along the same lines, scholars argue that other sculptural friezes at important early Buddhist stupas like Bharhut depict scenes from the life of the Buddha, with the Buddha represented in aniconic form—as an empty throne (above), a wheel signifying the Buddha’s creation of the Wheel of Law or Dharma (below, right), or footsteps (below, left), and sometimes even as a stupa (see the image at the top of this page). A third way to interpret the enlightenment scene from the Bharhut stupa and other so-called aniconic depictions of the Buddha is to read them as depictions of Buddhist doctrine or belief.

Imagining the Buddha’s Corporeal Body

This trend of depicting the Buddha in aniconic form continues until after the turn of the 1st century C.E. with the development of Mahayana Buddhism when we begin to see a large number of images of the Buddha in human or anthropomorphic form (below). These new, iconic images of the Buddha were particularly popular in the region of Gandhara (in present-day Pakistan) during the Kushana period and include depictions of the Buddha’s enlightenment at Bodh Gaya (below). These anthropomorphic images usher in a new phase of Buddhist art in which artists convey meaning through the depiction of special bodily marks (lakshanas) and hand gestures (mudras) of the Buddha. In this anthropomorphic image of the Buddha’s enlightenment, the artist depicts Prince Siddhartha seated on a throne, surrounded by the demon Mara and his army, who attempted—unsuccessfully—to thwart Prince Siddhartha’s attainment of enlightenment. At the moment of enlightenment, the prince reaches his right hand towards the ground in a gesture (or mudra, and specifically the bhumisparshamudra) ) of calling the earth to witness his spiritual awakening. In doing so he becomes the Buddha.

Additional resources:

Images of Bharhut stupa in Indian Museum, Kolkata

3-minute youtube video about Bharhut stupa

Late 19th century photographs in British Library Collection of British excavation of Bharhut stupa

Buddhism from the Freer Gallery of Art

Vidya Dehejia, “Aniconism and the Multivalence of Emblems,” Ars Orientalis vol. 21 (1991), pp. 45 – 66.

Susan L. Huntington, “Early Buddhist Art and the Theory of Aniconism,” Art Journal vol. 49.4 (1990), pp. 401 – 408.

Jatakas: the many lives of Buddha as Bodhisattva

Jatakas — the stories about virtues

Imagine a six-tusked elephant salvaging the lives of men while losing its own in an ordeal, or a monkey king saving the lives of his fellow monkeys by stretching his body between two trees to make a bridge for their safety. Stories like these recall tales told by parents or grandparents as bedtime stories for children. In a different context, however, these stories form an integral part of Buddhist Jataka tales.

The Jatakas are an important part of Buddhist art and literature. They describe the previous existences or births of the Buddha (the Enlightened One) when he appeared as Bodhisattvas (beings who are yet to attain enlightenment or moksha), in both human and non-human forms. These stories tell us how practicing different perfections or transcendental virtues (which are usually termed paramitas) are key to Buddhist approaches for attaining enlightenment (moksha) or the release from samsara, the endless cycle of rebirth.

Where to find the Jatakas

The literary text called the Jataka contains more than 500 tales and constitutes the tenth book of the fifteen texts written in the ancient Indic language of Pali that comprise the Khuddaka Nikaya of the Sutta Pitaka (the second of the Tripitaka or Buddhist Pali canon dealing with the doctrinal section of the Hinayana, a sect of Buddhism that emphasized the life of the Historical Buddha, Shakyamuni). The extant Jataka text that has come down to us is a commentary on the original Pali canonical Jataka book, which was in verse form. A few Jataka tales can also be traced to the Cariya Pitaka, the Buddhavamsa, and other parts of the Pali canon.

From story to a “Jataka”

Although it is beyond doubt that a large portion of the Jataka content is peculiar to Buddhism, these stories contain an unrivaled collection of folklore that likely circulated outside of Buddhist communities. A large number of Jatakas originally belonged to ancient Indian storytelling or narrative traditions that were both rich and varied. Telling stories, fables, anecdotes and fairy tales is a favorite method by which leaders of world religions seek more followers and increased popularity for their faiths. The inclusion of folk or popular components in the Jatakas ultimately enabled them to reach larger audiences through narrative elements that people could easily identify with. In some cases, a mundane or arbitrary story, originally unrelated to Buddhist ideas, was “buddhicized” and turned into a Jataka story.

Jatakas in art

Apart from the oral and literary forms, Jatakas reached the laity and monks through art, which proved to be a powerful tool in communicating Buddhist tenets and philosophy to a wide public. Jatakas are often found in sculptural reliefs or paintings in Buddhist stupas (Buddhist shrines with dome-shaped structures) and caves. It is no surprise, therefore, that the popularity of several Buddhist sites in what is now India, Bharhut, Sanchi, Amaravati, Ajanta and Nagarjunakonda, also feature brilliantly-produced Jataka depictions. Artists developed ingenious and visually effective methods to tell the Jataka stories without losing their essence and while making them easily understandable for a wide audience.

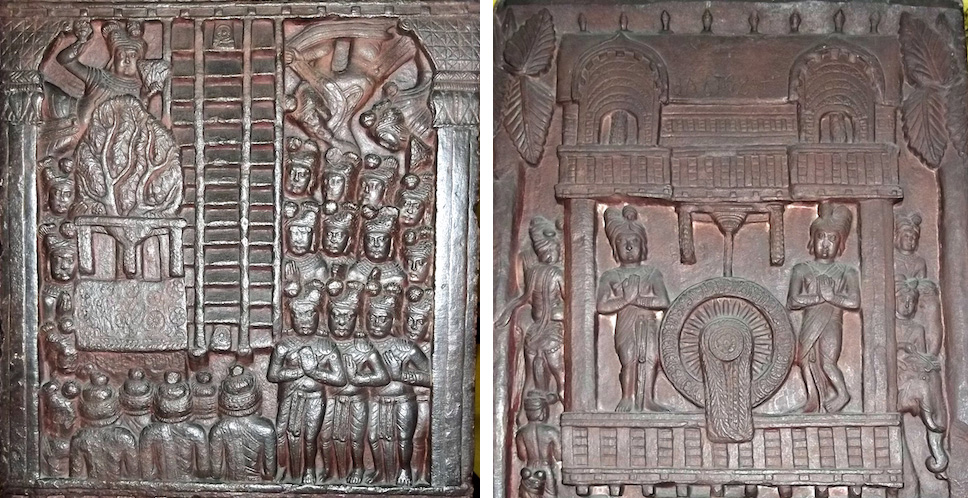

The story of the Great Monkey King at Bharhut

One Jataka story that became popular in Buddhist art is the Mahakapi Jataka. This Jataka describes how the Bodhisattva was born as a Great Monkey who dwelled in a beautiful Himalayan forest among a large troop of monkeys. According to the story, near the bank of the river Ganges a huge Banyan tree bore fruits with divine fragrance and flavor. Though the Great Monkey (the Bodhisattva) and his troop took utmost care to see that no fruit grew or fell from the branch that stretched towards the Ganges, one ripe fruit did fall into the river and was caught in the net of a fisherman who showed the fruit to the king of Benaras. The king went to the tree with his retinue and saw the monkeys eating the fruits. Annoyed, he ordered his archers to shoot them. The frightened monkeys approached the Bodhisattva, who comforted them and told them not to worry. He tried to make a bamboo bridge between the tree and another tree on the other side of the river. But somehow the bamboo shoot fell short of the length required to form the bridge. Realizing this, the Bodhisattva stretched himself at the end, so that his herd could pass safely over on his back. The monkeys escaped—treading on the back of the Bodhisattva. As the Mahakapi Jataka explains, the king was filled with deep emotion to see how the Bodhisattva endangered his own life for the safety of his retinue. The king commanded his attendants to safely bring down the Bodhisattva.

A stunning representation of this Jataka is found in a medallion at Bharhut (an important Buddhist site in the present-day state of Madhya Pradesh, India). We see several moments of the story in this one medallion. The scene is divided into two by a flowing river shown teeming with fish. Flanking the river are two trees: the one on the right is inhabited by the monkeys, and the other, smaller tree on the left is the tree they escape to. In the middle of these trees the Great Monkey (the Bodhisattva) has fastened one end of the bamboo stem to the top of the tree on the left and the other end to the ankle of his right leg. He clings to two smaller upper branches of the tree on the right to form a bridge.

The artist(s) depict monkeys actively moving between the two trees that frame this scene: several monkeys clamber amidst the branches of the large banyan, one monkey appears to be leaping over the Bodhisattva’s back, and two lucky monkeys have safely reached the far side. Below we see the next moment of the story with two men holding a piece a fabric as a safety net to catch the Great Monkey as he jumps down from the tree. In the final scene at the bottom, the Bodhisattva and the king sit across from one other, as the Bodhsiattva instructs the king in Buddhist law before dying from the wounds sustained during his dramatic feat to save the troop. The story tells us that the king then honored the Great Monkey with royal funeral rites.

Another version at Sanchi

Another depiction of the Mahakapi Jataka appears on the western gateway of the Great Stupa (Stupa 1) at Sanchi, also in Madhya Pradesh, India. The first scene, depicted at the bottom, shows the arrival of the king of Benaras, mounted on a horse accompanied by soldiers. The king is shown with a parasol or chatra over his head, which signifies his royal status. A feature that arouses curiosity is the portrayal of musicians who accompany the king—perhaps meant to accentuate the royal status of the king, suggesting that he travels with an entourage of attendants and musical accompaniment. To the right of the king an archer appears with bow and arrow aiming at the Bodhisattva (Great Monkey).

As at Bharhut, the artist(s) of the Sanchi relief show the Bodhisattva as the bridge by which monkeys escape to join the rest of the troop in the forest. On the left side of the river (which in this relief is full of active fish and rhythmic waves of water), two men, presumably following the order of the king, appear holding a sheet below the Great Monkey as he falls. The episodes depicted in the Sanchi panel give no indication of order through either time or cause and effect. Such is the complexity of this portrayal that even a viewer well-versed in this story must closely examine the panel, as art historian Vidya Dehejia puts it, to “read” it accurately. Apparently, the artist made this for an audience with previous knowledge of the Jataka stories.

The many other virtuous deeds and sacrifices of the Bodhisattva which make Jatakas extremely popular among the Buddhist community or sangha are included in such stories as Chaddanta, Vishvantara, Vidhurapandita, Ruru, Mahajanaka and Hamsa Jatakas. The Jatakas came to be portrayed in Central Asia, Afghanistan, China, Japan and Sri Lanka, leaving an indelible mark on Buddhist art and literature in the regions beyond the Indian subcontinent—becoming an inseparable part of Buddhist tradition.

Additional resources:

Buddhism and its Artistic Expression, from the Indian Museum, Kolkata

Paths to Perfection: Buddhist Art at the Freer|Sackler

Vidya Dehijia, Discourse in Early Buddhist Art: Visual Narratives of India (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1997).

———- “On Modes of Visual Narration in Early Buddhist Art,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 72, no. 3 (September, 1990), pp. 374-392.

The Jatakamala or Garland of Birth-Stories of Aryasura, translated by . J.S. Speyer (1st London ed. 1895; reprint, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1982).

The Jataka or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births, translated by various hands. ed. E.B. Cowell, 6 volumes (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2005).

John Marshall, A Guide to Sanchi (New Delhi: New Society, 1990).

S.C. Sarkar, A Study on the Jatakas and the Avadanas: Critical and Comparative, pt. 1 (Calcutta: Saraswat Library, 1981).

Four Buddhas at the American Museum of Natural History

by DR. LAUREL KENDALL, DR. MONIQUE SCOTT, DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Seated Gautama Buddha, 18th Century, cast brass, gilt (Thailand); Gandharan Seated Buddha with Double Halo, attributed to the 3rd Century, green-gray schist (Pakistan); Jizo, Kshitigarbha, Dhyani-Bodhisattao, 19th Century, wood, gold (Japan); Budai (Ho t’ai)/Maitreya, The Laughing Buddha, c. 1900, metal (China)

This video was produced in cooperation with the American Museum of Natural History.