2.9: Ancient Rome II

- Page ID

- 64925

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Roman Republic

Between the period of Kings and Emperors, there was the Roman Republic, whose most important political institution was the Senate.

c. 509 - 27 B.C.E.

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Rome

This three-in-one temple to “Jupiter Best and Greatest,” Juno, and Minerva was central in ancient Roman religion.

A temple on a hill

Like the Etruscans and Greeks before them, the Romans are known for having constructed monumental temples in highly visible locations. Situated atop the Capitoline Hill in the heart of the ancient city of Rome, the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus represented this tradition well (today the site is occupied by a piazza designed by the Renaissance artist Michelangelo, see photo below). Unfortunately, neglect, spoliation, and eventual site adaptation means that very little of the Temple of Jupiter remains for us to study. Despite its absence, however, the lasting impact of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus can be observed in the many Roman temples that emulated it, making it perhaps the most important of all Roman temples in terms of its cultural influence and design. (Watch this video to see where the Temple stood in the ancient city.)

Current State and Original Appearance(s)

Remains of the temple include portions of the tuff foundation and podium (see photo below), as well as some marble and terracotta architectural elements. Most of the structural remains can be viewed in situ (in their original setting) on the grounds of the Palazzo Caffarelli (today part of the Capitoline Museums), and surviving fragments are located within the Capitoline Museums.

Based on the surviving portions of the archaic foundation, the podium for the temple likely measured approximately 50m x 60m. Those dimensions are somewhat speculative, however, as there is no scholarly consensus on the precise measurements. The current best guess is that the temple was quite similar in plan to that of late-archaic Etruscan temples like the Temple of Minerva at Veii (also called the Portonaccio temple)—a high podium (platform) with a single frontal staircase leading to a three-column deep pronaos (porch) fronted by a hexastyle (six columns across) arrangement of columns. One of the defining features of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was its three-part (tripartite) interior with three adjacent cellae (rooms) for the three major deities honored within (Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva).

The earliest phase of the temple featured terracotta elements, including acroteria (sculptures on the roofline) and a large terracotta statue of Jupiter driving a quadriga (four-horse chariot). Inside the temple was another image of Jupiter—the cult statue reportedly sculpted by the famed archaic sculptor Vulca of Veii. This statue was painted red and served as the basis for the tradition of painting the faces of Roman generals during officially sanctioned triumphs.

In contrast with the modest terracotta (baked clay) that was used to adorn the earliest versions of the temple, several Roman sources note that the later reconstructions made during the period of the Roman empire featured much more extravagant materials. Ancient authors, including Plutarch, Cassius Dio, Suetonius, and Ammianus described the temple as outstanding in its quality and appearance, with a superstructure of Pentelic marble, gilded roof tiles, gold-plated doors, and elaborate pedimental relief sculpture.

History and Dedication

Although primarily dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the temple also included spaces for the worship of Juno and Minerva. Together, the three deities comprised what is known as the Capitoline Triad—a divine group significant to the Roman state religion. Jupiter, the Roman equivalent of Zeus, was the most significant of these deities. This is supported by the specific aspect of his worship noted in the full title of the cult—Iuppiter Optimus Maximus, Latin for “Jupiter, Best and Greatest.”

An important date for Rome

The temple was reportedly completed around 509 B.C.E.—the date itself is significant as it marks the purported year during which the Romans overthrew the monarchy (which was Etruscan, not Roman) and established a republican system of government. Thus, not only was the temple located in a prominent geographical location, it was also a lasting reminder of the moment when the Romans asserted their independence. This historical proximity of the founding of the Republic with the construction of the Temple of Jupiter may have also helped to lend support to its central role in Roman religion and to architectural design practice.

Destroyed and rebuilt

The building itself was destroyed and rebuilt several times in the Republican and Imperial periods, and benefitted from several restorations along the way. First destroyed in 83 B.C.E. during the civil wars of Sulla, the temple was rededicated and rebuilt during the 60s B.C.E. Augustus claimed to have restored the temple, most likely as part of his enormous building program that began during his rise to power in the first century B.C.E. The temple was again destroyed in 69 C.E., during the tumultuous “year of the four emperors.” Although rebuilt by the emperor Vespasian in the 70s C.E., the temple once more burned during a fire in 80 C.E. The emperor Domitian enacted the final major reconstruction of the temple during his reign, between 81 and 96 C.E.. The fact the temple was never neglected for very long is a testament to its perceived importance.

After the first century C.E., the temple seems to have retained its structural integrity until the emperor Theodosius eliminated public funds for the upkeep of pagan temples in 392 C.E. (Christianity had become the official state religion of the Roman Empire). Following this, the temple was spoliated several times in the Late Antique and Medieval eras. Eventually a grand residence, the Palazzo Caffarelli, was built on the site in the sixteenth century C.E.

Public Function

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was more than simply a standard religious building. From its earliest phases, the temple also seems to have been a repository for objects of ritual, cultural, and political significance. For example, the Sibylline Oracles (books containing the prophecy of the Sibyls) were kept at the site, as were some spoils of war, like the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal’s shield. In addition, the temple served as the end point for triumphs, a meeting place for the senate, a location for combined religious and political pageantry, an archive for public records, and a physical symbol of Rome’s supremacy and divine agency.

Sacrifice Panel of the Lost Arch of Marcus Aurelius

Perhaps the best depiction of the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus can be seen on the Sacrifice Panel from a now lost arch of the emperor Marcus Aurelius (above and detail, left). In this relief, Marcus Aurelius is shown in his role as Pontifex Maximus (chief priest) offering a sacrifice to Jupiter amidst a crowd of attendants. A temple with three doors, presumably the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, is portrayed in the background.

In this rendering, the temple is tetrastyle (four columns across the front—likely a truncated artistic representation due to the size of the panel) and of the Corinthian order. The pediment features Jupiter enthroned in the center while flanked by other deities; an intricately sculpted raking (sloping) cornice, surmounted at the apex by a quadriga (four-horse chariot), frames the scene.

Lasting Influence

Although the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was built in an Etruscan style and involved Etruscan craftsmen, it nevertheless serves as the origin point for the development of Roman temple-building tradition, which often incorporated local elements into a more broadly Roman template.

In terms of architectural history, the lasting significance of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus can be best recognized by its influence on Roman temple building from the last two centuries B.C.E up until the third century C.E. Imperial temples across the empire—including the Temple of Portunus at Rome (see photo above)—the Maison Carrée in France, and the many Capitolia (Temples dedicated to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva) of Roman colonies established in north Africa demonstrate an obvious visual connection to the Capitoline temple with a shared frontality, deep front porch, and rich sculptural adornment (some characteristics of which are shared by the Temple of Baalshamin at Palmyra). Yet, the influence of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus can also be seen in the overall Roman approach to designing architecture—monumental scale, urban setting, lavish decoration, and imposing elevation. Together, these elements are hallmarks of Roman temples and suggest that the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was an origin point for what would become a commonly understood architectural mark of Roman sovereignty over the Mediterranean world.

Additional resources:

The Temple of Capitoline Jupiter (Capitoline Museums)

Stefano De Angeli, “Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, Aedes, Templum (Fasi Tardo-Repubblicane e di età Imperiale” in Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, volume 3, edited by Eva Margareta Steinby (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1995), pp. 148-153.

Ellen Perry, “The Same, But Different: The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus through Time,” in Architecture of the Sacred: Space, Ritual, and Experience from Classical Greece to Byzantium, edited by Bonna Wescoat and Robert Ousterhout (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 175-200.

Samuel Ball Platner, “Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus” in A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, edited by Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1929), pp. 297-302.

Frank Sear, Roman Architecture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983).

Anna Mura Sommella, “Le recenti scoperte sul Campidoglio e la fondazione del tempio di Giove Capitolino.” Rendiconti della Pontificia Accademia Romana 70 (2000), pp. 57-80.

John Stamper, The Architecture of Roman Temples: The Republic to the Middle Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Gianluca Tagliamonte, “Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, Aedes, Templum (Fino All’ A. 83 a.C.)” in Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, volume 3, edited by Eva Margareta Steinby (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1995), pp. 144-148.

J.B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

Temple of Portunus, Rome

This small temple is a rare surviving example from the Roman Republic. It is both innovative and traditional.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Temple of Portunus (formerly known as, Fortuna Virilis), travertine, tufa, and stucco, c. 120-80 B.C.E., Rome.

The Temple of Portunus is a well preserved late second or early first century B.C.E. rectangular temple in Rome, Italy. Its dedication to the God Portunus—a divinity associated with livestock, keys, and harbors—is fitting given the building’s topographical position near the ancient river harbor of the city of Rome.

The city of Rome during its Republican phase was characterized, in part, by monumental architectural dedications made by leading, elite citizens, often in connection with key political or military accomplishments. Temples were a particularly popular choice in this category given their visibility and their utility for public events both sacred and secular.

The Temple of Portunus is located adjacent to a circular temple of the Corinthian order, now attributed to Herakles Victor. The assignation of the Temple of Portunus has been debated by scholars, with some referring to the temple as belonging to Fortuna Virilis (an aspect of the God Fortuna). This is now a minority view. The festival in honor of Portunus (the Portunalia) was celebrated on 17 August.

The Temple’s plan and construction

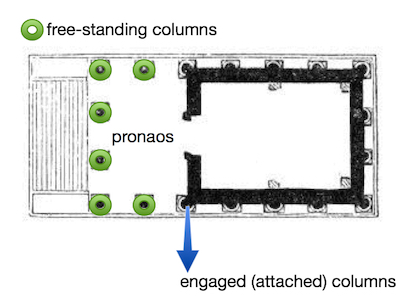

The temple has a rectangular footprint, measuring roughly 10.5 x 19 meters (36 x 62 Roman feet). Its plan may be referred to as pseudoperipteral, instead of a having a free-standing colonnade, or row of columns, on all four sides, the temple instead only has free-standing columns on its facade with engaged columns on its flanks and rear.

The pronoas (porch) of the temple supports an Ionic colonnade measuring four columns across by two columns deep, with the columns carved from travertine. The Ionic order can be most easily seen in the scroll-shaped capitals.There are five engaged columns on each side, and four across the back.

Overall the building has a composite structure, with both travertine and tufa being used for the superstructure (tufa is a type of stone consisting of consolidated volcanic ash, and travertine is a form of limestone). A stucco coating would have been applied to the tufa, giving it an appearance closer to that of the travertine.

The temple’s design incorporates elements from several architectural traditions. From the Italic tradition it takes its high podium (one ascends stairs to enter the pronaos), and strong frontality. From Hellenistic architecture comes the Ionic order columns, the engaged pilasters and columns. The use of permanent building materials, stone (as opposed to the Italic custom of superstructures in wood, terracotta, and mudbrick), also reflects changing practices. The temple itself represents the changing realities and shifting cultural landscape of the Mediterranean world at the close of the first millennium B.C.E.

The temple of Portunus resides on the Forum Boarium, a public space that was the site of the primary harbor of Rome. While the temple of Portunus is a bit smaller than other temples in the Forum Boarium and the adjacent Forum Holitorium, it fits into a general typology of Late Republican temple building.

The temple of Portunus finds perhaps its closest contemporary parallel in the Temple of the Sibyl at Tibur (modern Tivoli) which dates c. 150-125 B.C.E. The temple type embodied by the Temple of Portunus may also be found in Iulio-Claudian temple buildings such as the Maison Carrée at Nîmes in southern France.

Preservation and current state

The Temple of Portunus is obviously in an excellent state of preservation. In 872 C.E. the ancient temple was re-dedicated as a Christian shrine sacred to Santa Maria Egyziaca (Saint Mary of Egypt), leading to the preservation of the structure. The architecture has inspired many artists and architects over the centuries, including Andrea Palladio who studied the structure in the sixteenth century.

Neo-Classical architects were inspired by the form of the Temple of Portunus and it led to the construction of the Temple of Harmony, a folly in Somerset, England, dating to 1767 (below).

The Temple of Portunus is important not only for its well preserved architecture and the inspiration that architecture has fostered, but also as a reminder of what the built landscape of Rome was once like – dotted with temples large and small that became foci of a great deal of activity in the life of the city. Those temples that survive are reminders of that vibrancy as well as of the architectural traditions of the Romans themselves.

Backstory

The Temple of Portunus was put on the World Monuments Watch list in 2006. Overseen by the World Monuments Fund, this list highlights “cultural heritage sites around the world that are at risk from the forces of nature or the impact of social, political, and economic change,” providing them with “an opportunity to attract visibility, raise public awareness, foster local engagement in their protection, leverage new resources for conservation, advance innovation, and demonstrate effective solutions.”

Together with the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma and grants from private funders, the World Monuments Fund sponsored a restoration of the Temple of Portunus beginning in 2000. The temple had been partially restored and conservation measures put in place in the 1920s, but the activities undertaken in the last two decades utilized the latest technologies to complete a full restoration of the interior and exterior of the building. This included the cleaning and conservation of the frescoes, replacement of the roof (incorporating ancient roof tiles), anti-seismic measures, and the cleaning and restoration of the pediment, columns, and exterior walls. The newly-restored temple opened to the public in 2014.

The Temple of Portunus is one of the best-preserved examples of Roman Republican architecture, and efforts like those of the World Monuments Fund are ensuring that it continues to survive intact.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

Additional resources:

World Monuments Fund: Temple of Portunus

F. Coarelli, Il Foro Boario dalle origini alla fine della repubblica (Rome: Ed. Quasar, 1988).

R. Delbrueck, Hellenistische bauten in Latium (Strassburg, K.J. Trübner, 1907-12).

E. Fiechter, “Der Ionische Tempel am Ponte Rotto in Rom,” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 21 (1906), pp. 220-79.

J. W. Stamper, The Architecture of Roman Temples: The Republic to the Middle Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

A. Ziółkowski, The temples of Mid-Republican Rome and their historical and topographical context (Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider, 1992).

Temple of Portunus, Soprintendenza Speciale per il Colosseo, il Museo Nazionale Romano e l’Area Archeologica di Roma

Video with photos of the restoration from the World Monuments Fund

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\): More SmartHistory images…

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\): More SmartHistory images…

Maison Carrée

This well-preserved building in modern-day France is a textbook example of a Vitruvian temple.

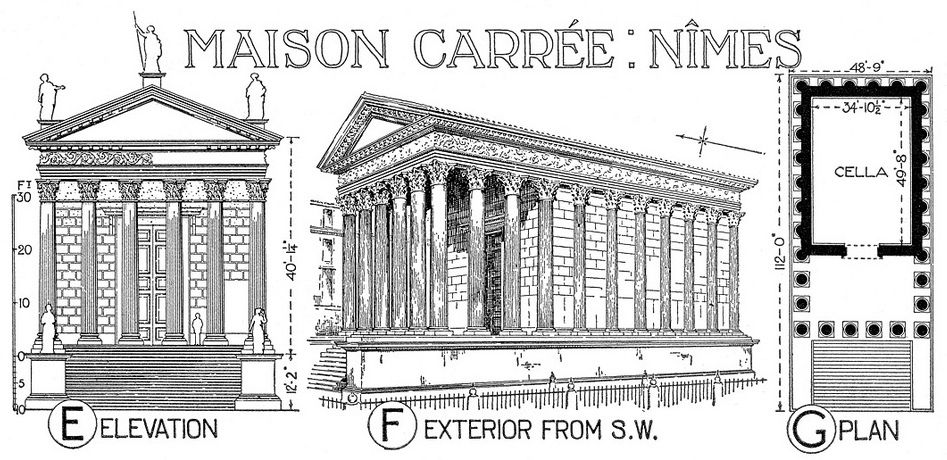

The so-called Maison Carrée or “square house” is an ancient Roman temple located in Nîmes in southern France. Nîmes was founded as a Roman colony (Colonia Nemausus) during the first century B.C.E. The Maison Carrée is an extremely well preserved ancient Roman building and represents a nearly textbook example of a Roman temple as described by the architectural writer Vitruvius.

Design and Plan

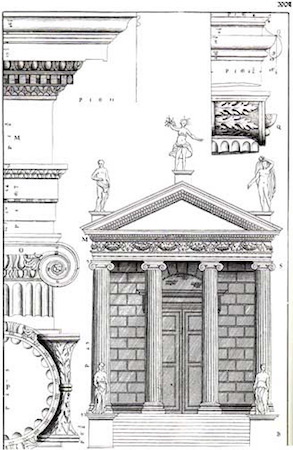

The frontal temple is a classic example of the Tuscan style temple as described by Vitruvius (who wrote On Architecture in the first century B.C.E.). This means that the building has a single cella (cult room), a deep porch, a frontal, axial orientation, and sits atop a high podium. The podium of the Maison Carrée rises to a height of 2.85 meters; the footprint of the temple measures 26.42 by 13.54 meters at the base.

The building is executed in the Corinthian order (easily identified by the acanthus leaf motifs on the capital) and is hexastyle in its plan (meaning it has six columns across the façade); twenty engaged columns line the flanks, yielding a pseudoperipteral arrangement (the front columns are free-standing but the columns on the sides and back are engaged, that is, attached to the wall).

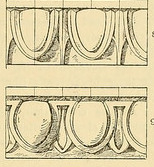

The temple has a very deep pronaos (porch). The superstructure is decorated with egg-and-dart motifs, with the architrave divided into three zones. The deep porch which puts an emphasis on the temple front and the pseudoperipteral arrangement clearly differentiate this from an ancient Greek temple.

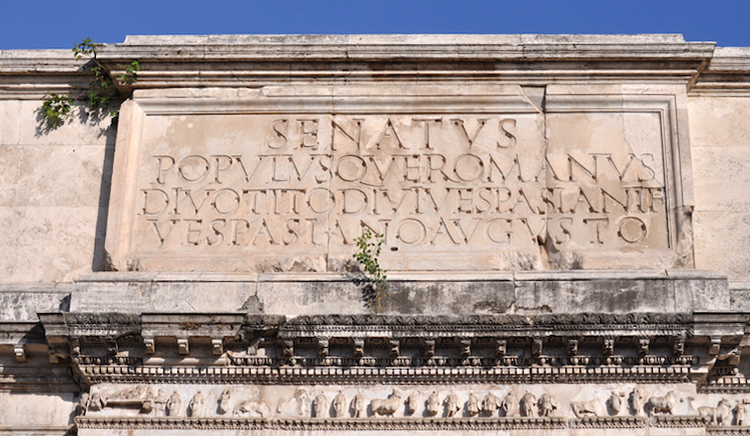

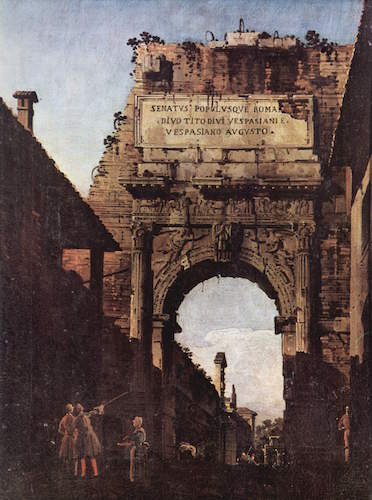

The temple once carried a dedicatory inscription that was removed in the Middle Ages. Following the reconstruction of the inscription in 1758, scholars believe that the dedication of the building honored Augustus’ grandsons and intended heirs, Caius and Lucius Caesar. The dedicatory inscription read, in translation, “To Gaius Caesar, son of Augustus, Consul; to Lucius Caesar, son of Augustus, Consul designate; to the princes of youth” (CIL XII, 3156). While not especially common within Italy during the time of the Iulio-Claudians, the worship of the emperor and the imperial family was more commonplace in the provinces of the Roman empire.

The late first century B.C.E. Temple of Augustus and Livia in located in Vienne, France (an ancient settlement of the Allobroges that received a Roman colony) is very similar in plan to the Maison Carrée. This temple was originally dedicated to Augustus alone, but in 41 C.E. the emperor Claudius re-dedicated the building to include Livia, his grandmother (and the wife of Augustus). Taken together these temples show us not only well preserved examples of early Imperial architecture but they also show the degree to which local elites would invest in monumental construction in order to celebrate the emperor and his family members. Just as honorific temples at Rome were sponsored by elites, construction in the provinces also often relied on elite members of the community to fill the role of artistic patron.

Additional resources:

Robert Amy, “L’inscription de la maison carrée de Nîmes”, Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 114.4 (1970) pp. 670-686.

Robert Amy and Pierre Gros, La Maison Carrée de Nîmes (Supplementa à “Gallia”; 38) (Paris: Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1979).

James C. Anderson, jr. “Anachronism in the Roman Architecture of Gaul: the Date of the Maison Carrée at Nîmes,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 60 (2001) pp. 68-79

James C. Anderson, jr., Roman Architecture in Provence (Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Jean-Charles Balty, Études sur la Maison Carrée de Nimes. (Bruxelles-Berchem, Latomus, revue d’études latines, 1960).

Pierre Gros, “L’augusteum de Nîmes”, Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise 17.1 (1984) pp. 123-134.

Pierre Gros, L’architecture romaine : du début du IIIe siècle av. J.-C. à la fin du Haut-Empire. 1, Les monuments publics (Paris: Picard, 2001).

John Bryan Ward-Perkins, “From Republic to Empire: Reflections on the Early Provincial Architecture of the Roman West”, The Journal of Roman Studies, 60 (1970), pp. 1-19.

Capitoline She-wolf

Rome’s eternal symbol?

If one could choose any animal to become one’s mother, how many people would choose a wolf? Wolves are not known to be the gentlest of animals, and in the ancient world, when many people made their living as shepherds, wolves could pose a significant threat. But for reasons we do not understand, the Romans chose a wolf as their symbol. According to Roman mythology, the city’s twin founders Romulus and Remus were abandoned on the banks of the Tiber River when they were infants. A she-wolf saved their lives by letting them suckle. The image of this miracle quickly became a symbol of the city of Rome, appearing on coinage in the third century B.C.E. and continuing to appear on public monuments from trash-cans to lampposts in the city even to this day. But the most famous image of the she-wolf and twins may not be ancient at all—at least not entirely.

Description

The Capitoline She-wolf (Italian: Lupa capitolina) takes its name from its location—the statue is housed in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. The She-wolf statue is a fully worked bronze composition that is intended for 360 degree viewing. In other words the viewer can get an equally good view from all directions: there is no “correct” point of view. The She-wolf is depicted standing in a stationary pose. The body is out of proportion, because its neck is much too long for its face and flanks. The incised details of the neck show thick, s-curled fur which ends with unnatural beads around the face and behind the forelegs. The wolf’s body is leaner in front than in the rear: its ribs are visible, as are the muscles of its forelegs, while in the back the musculature is less detailed, suggesting less tone. Its head curves in towards its tail; the ears curve back. The children themselves have a more dynamic posture: one sits with his feet splaying to either side, while the other kneels beside him. Both face upwards. They, too, are lean, with no trace of baby fat.

Hollow-cast bronze: How was it made?

The She-wolf is a hollow-cast bronze statue that is just under life-sized. Hollow casting is one of the many ways that metal sculptures were made in the ancient world. It was the typical method for large-scale bronze statues.

In antiquity, hollow casting (also known as “lost-wax casting”) could be a lengthy procedure. A large sculpture was made in many smaller pieces, and these were joined as the last step of the process. A sculptor first made a model of the statue in a less-valuable medium, such as clay. He then coated the model with a second model, which was made in multiple pieces so it could be removed. Once removed, the second model was coated in wax and another layer of clay. The second and third models were then attached to each other and fired, leaving a hollow space as the wax melted. Molten metal was poured in to replace the wax, and the molds were (at last) removed only when the metal had cooled and set. In the case of large statues, the pieces were soldered together and polished as a final step.

But although the She-wolf is hollow-cast, it is not made of multiple pieces. This has raised significant questions about whether the wolf is ancient at all.

Questions of chronology

While it was known for some time that the twins are Renaissance additions to the sculpture, it was not until 2006 that the chronology of the She-wolf itself was challenged. Long believed to date to fifth century B.C.E. Etruria (Etruscan culture), the She-wolf’s date is now debated. If ancient, the original sculpture probably would not have depicted Rome’s she-wolf. We do know that Romans engaged in regional trade that led them to acquire art objects from surrounding areas, including Etruria (Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.45).

But new laboratory analysis suggests that the She-wolfis not ancient and was made in the Middle Ages, specifically the twelfth century C.E. Questions about the authenticity of the She-wolf were first raised when the statue was restored in the late 1990s. At that time, conservators realized that the casting technique used to make it is not the same as the hollow casting technique used on other large-scale bronze sculptures. Instead of using multiple molds, as described above, the She-wolf is made as a single piece. Proponents of this view argue that the wolf is more similar stylistically to medieval bronzes. Proponents of the Etruscan date claim that the few surviving Etruscan large-scale bronze statues are stylistically similar to the She-wolf.

The claim that the She-wolf is medieval has generated a lot of controversy in Italy and among scholars of ancient Rome. Several respected researchers have publicly disputed the new findings and maintain the She-wolf’s Etruscan provenance. Physical and chemical testing on the bronze has been inconclusive about the date. The Capitoline Museums admit both possibilities in the object’s description.

Conclusion

Although the debate continues with regard to the date of the Capitoline She-wolf, either interpretation offers interesting points for analysis. The only definitive testimony suggests that materials used in casting the wolf came from both Sardinia and Rome. If the work is from the fifth century B.C.E., we can use that evidence to analyze trade patterns in Italy. Remembering that the wolf was originally cast without the twins—no matter what date we assign to the wolf sculpture—we can try to imagine the original significance of the statue.

On the other hand, if the wolf is medieval, what was its original function? We should not think that a medieval wolf is any less valuable just because it is more recent in its date of manufacture. In fact, a pastiche Capitoline She-wolf might be an even better symbol of Rome: a Renaissance addition to a medieval statue that recreates the ancient symbol of the eternal city.

Additional resources:

This work at the Capitoline Museums

View this work in the Capitoline Museum gallery

Etruscan bronzes on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Medieval casting technique, including a video, from the Victoria and Albert Museum

M. R. Alföldi, E. Formigli, and J. Fried, Die römische Wölfin: ein antikes Monument stürzt von seinem Sockel = The Lupa Romana: an antique monument falls from her pedestal (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2011).

G. Bartoloni and A. M. Carruba, La lupa capitolina: nuove prospettive di studio : incontro-dibattito in occasione della pubblicazione del volume di Anna Maria Carruba, La lupa capitolina: un bronzo medievale Sapienza, Università di Roma, Roma 28 febbraio 2008 (Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider, 2008).

Andrea Carandini and R. Cappelli, Roma: Romolo, Remo e la fondazione della città (Milan: Electa, 2000).

A. M. Carruba and L. De Masi, La Lupa capitolina: un bronzo medievale (Rome: De Luca, 2006).

C. Dulière, Lupa romana: Recherches d’Iconographie et Essai d’Interprétation (Rome: Institut historique belge de Rome, 1979).

A. W. J. Holleman, “The Ogulnii Monument at Rome,” Mnemosyne 40.3/4 (1987), pp. 427-429.

A. La Regina, “La lupa del Campidoglio è medieval: la prova è nel test al carbonio,” La Repubblica July 9, 2008

C. Mazzoni, She-Wolf: The Story of a Roman Icon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

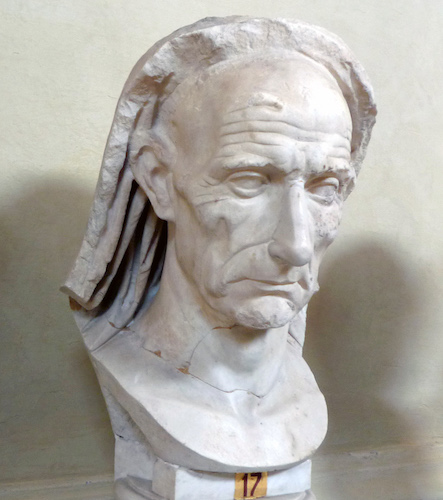

Capitoline Brutus

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Once identified as the founder of the Roman Republic, debate over this figure’s true identity rages on.

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Capitoline Brutus, 4th-3rd century B.C.E. bronze, 69 cm (Capitoline Museums, Rome)

Backstory

We know that the Capitoline Brutus was found somewhere in Rome during the sixteenth century, but there is no recorded findspot for this sculpture. In 1564 it was officially bequeathed to the city of Rome by Cardinal Rodolfo Pio da Carpi, an Italian scholar and collector who owned a large trove of ancient artifacts, but there is no known evidence of its original provenance.

In the sixteenth century, at the time of Pio da Carpi’s bequest, this sculpture was already known among antiquarians as Lucius Junius Brutus (who founded the Roman Republic in the 6th century B.C.E.), and this belief continued through the centuries. The bust eventually became a touchstone of revolutionary sentiment: after Napoleon’s invasion of northern Italy in the late 1790s, he staged a triumphal procession across Paris that conspicuously displayed his “art loot” from the campaign. “Rome is no more in Rome. It is now in Paris,” was the chorus of a song that accompanied the march. For Napoleon, the cultural and political meanings associated with ancient Roman art—and particularly the Capitoline Brutus—were key to shoring up his image as the leader of the new capital of Europe. According to art historian Patricia Mainardi, the Brutus was “carried at the end of the march and ceremonially placed on a pedestal before the Altar of the Fatherland,” with a plaque stating “Rome was first governed by kings: / Junius Brutus gave it liberty and the Republic.”

The sculpture was returned to Rome in 1814-15, after Napoleon’s defeat, but its interpretation as the portrait of Brutus lived on. As they did with the Portrait Bust of a Flavian Woman, art historians throughout the nineteenth century debated the identity of the sitter based on its resemblance to other portraits, such as those found on coins. (These objects selected for comparison are called “comparanda.”) However, without a sure archeological findspot, we have no way of knowing who this sculpture actually represents. The mystery of the Capitoline Brutus demonstrates how myths about particular objects can grow into stories that become larger than the objects themselves—but these stories are not necessarily grounded in archeological facts.

There is still a need not only a need for proper archeological excavation and documentation of ancient objects, but also for properly-documented objects to be prioritized within the canon of the history of visual culture. Though the Capitoline Brutus is aesthetically pleasing and in good condition, the most we can do is guess about its original history. Other objects—ones with recorded findspots—can help us learn much more about the cultures and artists that produced them, even if they may be less overtly enticing to the eyes.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

Additional resources:

This work at the Capitoline Museums

Peter Holliday, “Capitoline Brutus,” in An Encyclopedia of the History of Classical Archaeology, ed. Nancy Thomson de Grummond (New York: Routledge, 1997), n.p.

Patricia Mainardi, “Assuring the Empire of the Future: The 1798 Fête de la Liberté,” Art Journal vol. 48, no. 2 (Summer 1989), pages 155-163.

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Tomb of the Scipios and the sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus

Even in death, great Roman families were concerned with reinforcing and projecting their status.

Image and status

The latter days of the Roman Republican period witnessed socio-economic upheaval, and a long-established social order found itself threatened by newcomers who were wealthy but lacking in illustrious social pedigrees. Roman aristocrats in the patrician class (those threatened by this socio-economic upheaval) linked their ancestors to the founders of the Roman state, and projected an image of themselves as aged and wise as a measure of their experience and acumen (see Head of a Roman Patrician).

Since image and status are frequently linked, these aristocrats had long relied on display as part of cultivating their status. Whether this was the display of the images of illustrious family members in the atrium of their houses (so-called imagines), or the constructions of tombs or other patronage projects, material culture mattered in maintaining status. The Late Republican period (the late 2nd and 1st centuries B.C.E.) witnessed several significant examples of this attempt to maintain status in a changing world.

The family of the Cornelii Scipiones

The Cornelii Scipiones were among the most famous Romans of all. Their ancestors had won many victories—including those of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus (who died c. 280 B.C.E.) and Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (who died c. 183 B.C.E.), the victor in the Second Punic War. The family tomb of the Cornelii Scipiones, located along the Via Appia leading south from the city of Rome, was first rediscovered in 1614. Its remains constitute one of the most important examples of Late Republican funerary culture at Rome and demonstrate how an illustrious family worked to maintain its image in a changing world.

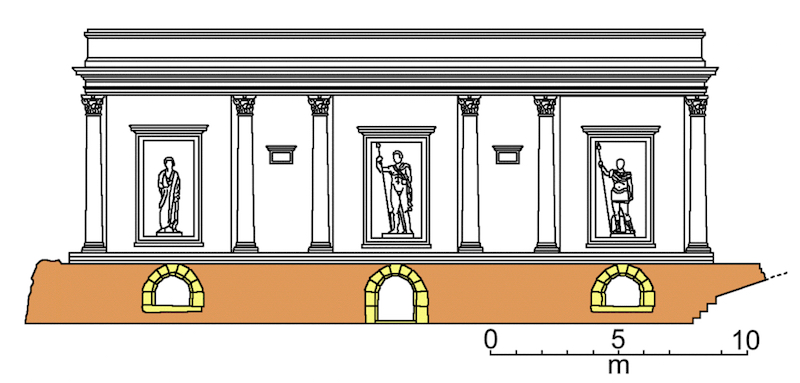

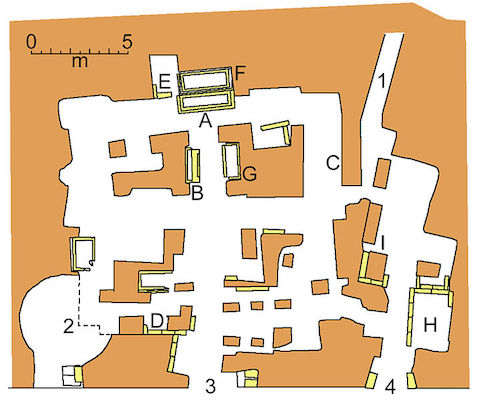

The Tomb

The Tomb of the Scipios is a subterranean, rock-cut tomb (hypogeum) composed of irregular chambers and connecting corridors that provide niches for burials (see plan and interior view below).

The tomb was begun in the early years of the third century B.C.E. and continued in use until the first century C.E. The family’s patriarch, Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, who served as consul in 298 B.C.E. is the most prominent occupant of the tomb. Barbatus was buried in a monumental stone sarcophagus with a Latin inscription (see below). Other family members occupy other parts of the tomb, in many cases with inscriptions identifying the individuals and charting their public careers.

As the tomb faced an important roadway, it came to have an elaborate façade in its later phases. This façade likely dates to c. 150 B.C.E. or later when the family renovated and expanded the tomb. In addition to the architectural elements of the façade, a fresco depicting a processional scene—perhaps of famous members of the Cornelii Scipiones—adorned the tomb.

The Sarcophagus of Barbatus

Scipio Barbatus was deposited in an elaborately carved sarcophagus (today the original is in the Vatican Museums—image below, and a plaster cast is in situ—image here). The façade of the sarcophagus is decorated with a Doric frieze and volute scrolls adorn the lid (watch a video about the classical orders). It included an elaborate Latin epitaph that was modified in antiquity, with some earlier text being erased. The Scipios were always keen to maintain family ties and support their ancestry at any cost. The extant text of the Barbatus epitaph records civic career achievements (Barbatus served as consul, censor, and aedile) and military achievements. In the latter category Barbatus was famous in Rome’s third century B.C.E. wars with the Samnites; the epitaph tells the reader that he captured Taurasia and Cisauna in Samnium, in addition to subduing the region of Lucania (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI, 1285).

Conclusion

The Tomb of the Scipios is an important monument that demonstrates Roman methods of using images to reinforce and project status. The competition to maintain social rank and position was fierce, and latter day members of the Cornelian family (gens Cornelia) were indeed trading on the names and reputations of their more famous ancestors as they themselves struggled for traction in the tumultuous period at the end of the Roman Republic.

Below is a Google photosphere, showing a Late Republican columbarium (for storage of funerary urns), adjacent to the Tomb of the Scipios that was used for cremation burials and, together with the elite Tomb of the Scipios, was located within a large necropolis located along the Via Appia exiting the city of Rome from the south:

Additional resources:

Roman Funerary Rituals (SmartHistory essay)

Filippo Coarelli, Il sepolcro degli Scipioni a Roma (Rome: Fratelli Palombi, 1988).

Filippo Coarelli, Rome and environs: an archaeological guide, trans. J. J. Clauss and D. Harmon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

Janos Fedak, Monumental tombs of the Hellenistic age: a study of selected tombs from the pre-classical to the early imperial era (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990).

Harriet Flower, Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in Roman Culture (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996).

Peter J. Holliday, The origins of Roman historical commemoration in the visual arts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, “Housing the Dead: the tomb as house in Roman Italy”, in L. Brink and D. A. Green (eds.) Commemorating the Dead. Texts and Artifacts in Context (Berlin, New York: de Gruyter) 39-77.

Veristic male portrait

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

With age comes experience, and sculptors in the Roman Republic highlighted seniority—warts and all.

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Veristic male portrait (similar to Head of a Roman Patrician), early 1st Century B.C.E., marble, life size (Vatican Museums, Rome)

Additional resources:

Roman Portrait Sculpture: The Stylistic Cycle on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

D. Jackson, “Verism and the Ancestral Portrait,” Greece & Rome 34.1 (1987):32-47.

D. E. E. Kleiner, Roman Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

G. M. A. Richter, “The Origin of Verism in Roman Portraits,” Journal of Roman Studies 45.1-2 (1955):39-46.

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

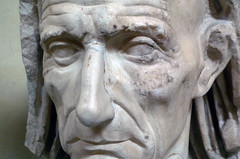

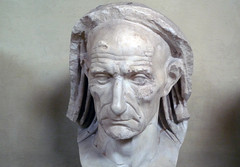

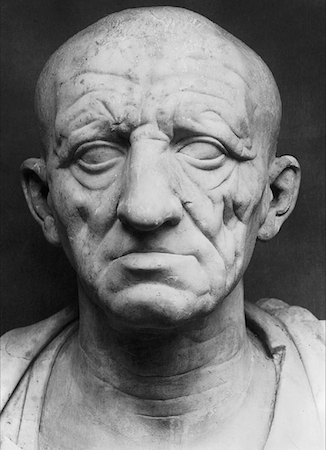

Head of a Roman Patrician

Seemingly wrinkled and toothless, with sagging jowls, the face of a Roman aristocrat stares at us across the ages. In the aesthetic parlance of the Late Roman Republic, the physical traits of this portrait image are meant to convey seriousness of mind (gravitas) and the virtue (virtus) of a public career by demonstrating the way in which the subject literally wears the marks of his endeavors. While this representational strategy might seem unusual in the post-modern world, in the waning days of the Roman Republic it was an effective means of competing in an ever more complex socio-political arena.

The portrait

This portrait head, now housed in the Palazzo Torlonia in Rome, Italy, comes from Otricoli (ancient Ocriculum) and dates to the middle of the first century B.C.E. The name of the individual depicted is now unknown, but the portrait is a powerful representation of a male aristocrat with a hooked nose and strong cheekbones. The figure is frontal without any hint of dynamism or emotion—this sets the portrait apart from some of its near contemporaries. The portrait head is characterized by deep wrinkles, a furrowed brow, and generally an appearance of sagging, sunken skin—all indicative of the veristic style of Roman portraiture.

Verism

Verism can be defined as a sort of hyperrealism in sculpture where the naturally occurring features of the subject are exaggerated, often to the point of absurdity. In the case of Roman Republican portraiture, middle age males adopt veristic tendencies in their portraiture to such an extent that they appear to be extremely aged and care worn. This stylistic tendency is influenced both by the tradition of ancestral imagines as well as a deep-seated respect for family, tradition, and ancestry. The imagines were essentially death masks of notable ancestors that were kept and displayed by the family. In the case of aristocratic families these wax masks were used at subsequent funerals so that an actor might portray the deceased ancestors in a sort of familial parade (Polybius History 6.53.54). The ancestor cult, in turn, influenced a deep connection to family. For Late Republican politicians without any famous ancestors (a group famously known as ‘new men’ or ‘homines novi’) the need was even more acute—and verism rode to the rescue. The adoption of such an austere and wizened visage was a tactic to lend familial gravitas to families who had none—and thus (hopefully) increase the chances of the aristocrat’s success in both politics and business. This jockeying for position very much characterized the scene at Rome in the waning days of the Roman Republic and the Otricoli head is a reminder that one’s public image played a major role in what was a turbulent time in Roman history.

Additional Resources:

Roman Portrait Sculpture: The Stylistic Cycle on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

K. Cokayne, Experiencing Old Age in Ancient Rome (London: Routledge, 2003).

H. I. Flower, Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in the Roman Republic (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996).

E. Gruen, Culture and National Identity in Republican Rome (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992).

D. Jackson, “Verism and the Ancestral Portrait,” Greece & Rome 34.1 (1987):32-47.

D. E. E. Kleiner, Roman Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

M. Papini, Antichi volti della Repubblica: la ritrattistica in Italia centrale tra IV e II secolo a.C. 2 v. (Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider, 2004).

G. M. A. Richter, “The Origin of Verism in Roman Portraits,” Journal of Roman Studies 45.1-2 (1955):39-46.

J. Tanner, “Portraits, Power, and Patronage in the Late Roman Republic,” Journal of Roman Studies 90 (2000), pp. 18-50.

Early Empire

With Augustus, the Roman Empire begins, and so does a 200-year period of peace and stability known as the Pax Romana.

27 B.C.E. - 117 C.E.

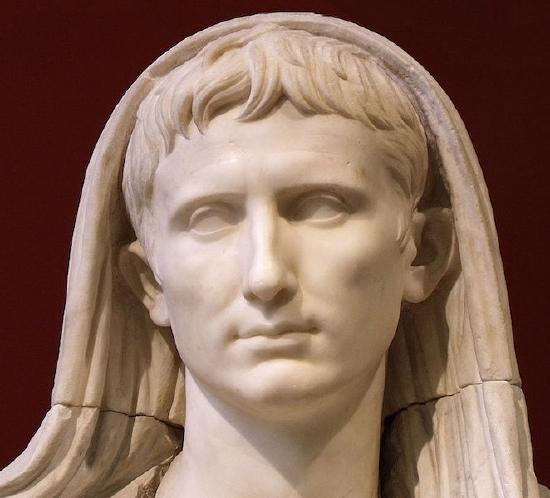

Augustus of Primaporta

by JULIA FISCHER

Nothing was more important to a Roman emperor than his image.

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Augustus of Primaporta, 1st century C.E. (Vatican Museums)

Augustus and the power of images

Today, politicians think very carefully about how they will be photographed. Think about all the campaign commercials and print ads we are bombarded with every election season. These images tell us a lot about the candidate, including what they stand for and what agendas they are promoting. Similarly, Roman art was closely intertwined with politics and propaganda. This is especially true with portraits of Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire; Augustus invoked the power of imagery to communicate his ideology.

Augustus of Primaporta

One of Augustus’ most famous portraits is the so-called Augustus of Primaporta of 20 B.C.E. (the sculpture gets its name from the town in Italy where it was found in 1863). At first glance this statue might appear to simply resemble a portrait of Augustus as an orator and general, but this sculpture also communicates a good deal about the emperor’s power and ideology. In fact, in this portrait Augustus shows himself as a great military victor and a staunch supporter of Roman religion. The statue also foretells the 200 year period of peace that Augustus initiated, called the Pax Romana.

Recalling the Golden Age of ancient Greece

In this marble freestanding sculpture, Augustus stands in a contrapposto pose (a relaxed pose where one leg bears weight). The emperor wears military regalia and his right arm is outstretched, demonstrating that the emperor is addressing his troops. We immediately sense the emperor’s power as the leader of the army and a military conqueror.

Delving further into the composition of the Primaporta statue, a distinct resemblance to Polykleitos’ Doryphoros, a Classical Greek sculpture of the fifth century B.C.E., is apparent. Both have a similar contrapposto stance and both are idealized. That is to say that both Augustus and the Spear-Bearer are portrayed as youthful and flawless individuals: they are perfect. The Romans often modeled their art on Greek predecessors. This is significant because Augustus is essentially depicting himself with the perfect body of a Greek athlete: he is youthful and virile, despite the fact that he was middle-aged at the time of the sculpture’s commissioning. Furthermore, by modeling the Primaporta statue on such an iconic Greek sculpture created during the height of Athens’ influence and power, Augustus connects himself to the Golden Age of that previous civilization.

The cupid and dolphin

So far the message of the Augustus of Primaporta is clear: he is an excellent orator and military victor with the youthful and perfect body of a Greek athlete. Is that all there is to this sculpture? Definitely not! The sculpture contains even more symbolism. First, at Augustus’ right leg is cupid figure riding a dolphin.

The dolphin became a symbol of Augustus’ great naval victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, a conquest that made Augustus the sole ruler of the Empire. The cupid astride the dolphin sends another message too: that Augustus is descended from the gods. Cupid is the son of Venus, the Roman goddess of love. Julius Caesar, the adoptive father of Augustus, claimed to be descended from Venus and therefore Augustus also shared this connection to the gods.

The breastplate

Finally, Augustus is wearing a cuirass, or breastplate, that is covered with figures that communicate additional propagandistic messages. Scholars debate over the identification over each of these figures, but the basic meaning is clear: Augustus has the gods on his side, he is an international military victor, and he is the bringer of the Pax Romana, a peace that encompasses all the lands of the Roman Empire.

In the central zone of the cuirass are two figures, a Roman and a Parthian. On the right, the enemy Parthian returns military standards. This is a direct reference to an international diplomatic victory of Augustus in 20 B.C.E., when these standards were finally returned to Rome after a previous battle.

Surrounding this central zone are gods and personifications. At the top are Sol and Caelus, the sun and sky gods respectively. On the sides of the breastplate are female personifications of countries conquered by Augustus. These gods and personifications refer to the Pax Romana. The message is that the sun is going to shine on all regions of the Roman Empire, bringing peace and prosperity to all citizens. And of course, Augustus is the one who is responsible for this abundance throughout the Empire.

Beneath the female personifications are Apollo and Diana, two major deities in the Roman pantheon; clearly Augustus is favored by these important deities and their appearance here demonstrates that the emperor supports traditional Roman religion. At the very bottom of the cuirass is Tellus, the earth goddess, who cradles two babies and holds a cornucopia. Tellus is an additional allusion to the Pax Romana as she is a symbol of fertility with her healthy babies and overflowing horn of plenty.

Not simply a portrait

The Augustus of Primaporta is one of the ways that the ancients used art for propagandistic purposes. Overall, this statue is not simply a portrait of the emperor, it expresses Augustus’ connection to the past, his role as a military victor, his connection to the gods, and his role as the bringer of the Roman Peace.

Additional resources:

View this work at the Vatican Museums

D. E. E. Kleiner, Roman Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

John Pollini, From Republic to Empire: Rhetoric, Religion, and Power in the Visual Culture of Ancient Rome (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012).

Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990).

Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars on Perseus Digital Library

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Ara Pacis

Augustus is said to have found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble—this altar symbolizes his golden age.

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace), 9 B.C.E. (Ara Pacis Museum, Rome, Italy)

The Roman state religion in microcosm

The festivities of the Roman state religion were steeped in tradition and ritual symbolism. Sacred offerings to the gods, consultations with priests and diviners, ritual formulae, communal feasting—were all practices aimed at fostering and maintaining social cohesion and communicating authority. It could perhaps be argued that the Ara Pacis Augustae—the Altar of Augustan Peace—represents in luxurious, stately microcosm the practices of the Roman state religion in a way that is simultaneously elegant and pragmatic.

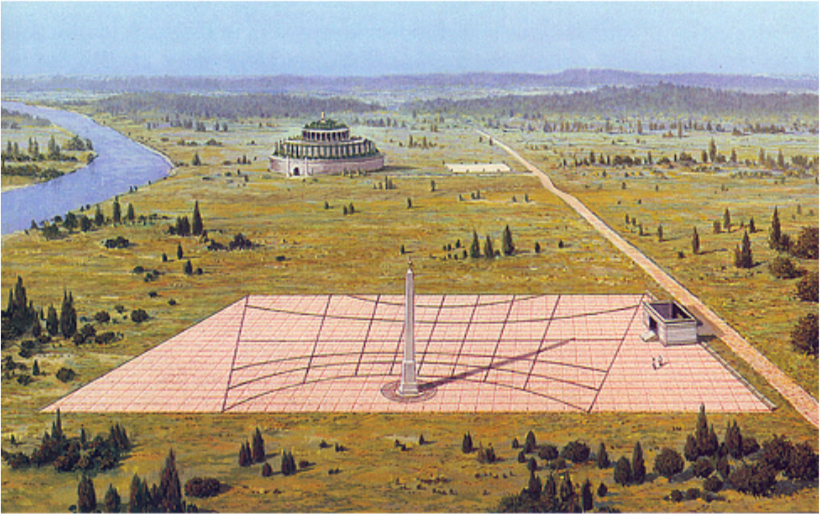

Vowed on July 4, 13 B.C.E., and dedicated on January 30, 9 B.C.E., the monument stood proudly in the Campus Martius in Rome (a level area between several of Rome’s hills and the Tiber River). It was adjacent to architectural complexes that cultivated and proudly displayed messages about the power, legitimacy, and suitability of their patron—the emperor Augustus. Now excavated, restored, and reassembled in a sleek modern pavilion designed by architect Richard Meier (2006), the Ara Pacis continues to inspire and challenge us as we think about ancient Rome.

Augustus himself discusses the Ara Pacis in his epigraphical memoir, Res Gestae Divi Augusti (“Deeds of the Divine Augustus”) that was promulgated upon his death in 14 C.E. Augustus states “When I returned to Rome from Spain and Gaul, having successfully accomplished deeds in those provinces … the senate voted to consecrate the altar of August Peace in the Campus Martius … on which it ordered the magistrates and priests and Vestal virgins to offer annual sacrifices” (Aug. RG 12).

An open-air altar for sacrifice

The Ara Pacis is, at its simplest, an open-air altar for blood sacrifice associated with the Roman state religion. The ritual slaughtering and offering of animals in Roman religion was routine, and such rites usually took place outdoors. The placement of the Ara Pacis in the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) along the Via Lata (now the Via del Corso) situated it close to other key Augustan monuments, notably the Horologium Augusti (a giant sundial) and the Mausoleum of Augustus.

The significance of the topographical placement would have been quite evident to ancient Romans. This complex of Augustan monuments made a clear statement about Augustus’ physical transformation of Rome’s urban landscape. The dedication to a rather abstract notion of peace (pax) is significant in that Augustus advertises the fact that he has restored peace to the Roman state after a long period of internal and external turmoil.

The altar (ara) itself sits within a monumental stone screen that has been elaborated with bas relief (low relief) sculpture, with the panels combining to form a programmatic mytho-historical narrative about Augustus and his administration, as well as about Rome’s deep roots. The altar enclosure is roughly square while the altar itself sits atop a raised podium that is accessible via a narrow stairway.

The Outer screen—processional scenes

Processional scenes occupy the north and south flanks of the altar screen. The solemn figures, all properly clad for a rite of the state religion, proceed in the direction of the altar itself, ready to participate in the ritual. The figures all advance toward the west. The occasion depicted would seem to be a celebration of the peace (Pax) that Augustus had restored to the Roman empire. In addition four main groups of people are evident in the processions: (1) the lictors (the official bodyguards of magistrates), (2) priests from the major collegia of Rome, (3) members of the Imperial household, including women and children, and (4) attendants. There has been a good deal of scholarly discussion focused on two of three non-Roman children who are depicted.

The north processional frieze, made up of priests and members of the Imperial household, is comprised of 46 figures. The priestly colleges (religious associations) represented include the Septemviri epulones (“seven men for sacrificial banquets”—they arranged public feasts connected to sacred holidays), whose members here carry an incense box (image above), and the quindecimviri sacris faciundis (“fifteen men to perform sacred actions”— their main duty was to guard and consult the Sibylline books (oracular texts) at the request of the Senate). Members of the imperial family, including Octavia Minor, follow behind.

A good deal of modern restoration has been undertaken on the north wall, with many heads heavily restored or replaced. The south wall of the exterior screen depicts Augustus and his immediate family. The identification of the individual figures has been the source of a great deal of scholarly debate. Depicted here are Augustus (damaged, he appears at the far left in the image above) and Marcus Agrippa (friend, son-in-law, and lieutenant to Augustus, he appears, hooded, image below), along with other members of the imperial house. All of those present are dressed in ceremonial garb appropriate for the state sacrifice. The presence of state priests known as flamens (flamines) further indicate the solemnity of the occasion.

A running, vegetal frieze runs parallel to the processional friezes on the lower register. This vegetal frieze emphasizes the fertility and abundance of the lands, a clear benefit of living in a time of peace.

Mythological panels

Accompanying the processional friezes are four mythological panels that adorn the altar screen on its shorter sides. Each of these panels depicts a distinct scene:

- a scene of a bearded male making sacrifice (below)

- a scene of seated female goddess amid the fertility of Italy (also below)

- a fragmentary scene with Romulus and Remus in the Lupercal grotto (where these two mythic founders of Rome were suckled by a she-wolf)

- and a fragmentary panel showing Roma (the personification of Rome) as a seated goddess.

Since the early twentieth century, the mainstream interpretation of the sacrifice panel (above) has been that the scene depicts the Trojan hero Aeneas arriving in Italy and making a sacrifice to Juno. A recent re-interpretation offered by Paul Rehak argues instead that the bearded man is not Aeneas, but Numa Pompilius, Rome’s second king. In Rehak’s theory, Numa, renowned as a peaceful ruler and the founder of Roman religion, provides a counterbalance to the warlike Romulus on the opposite panel.

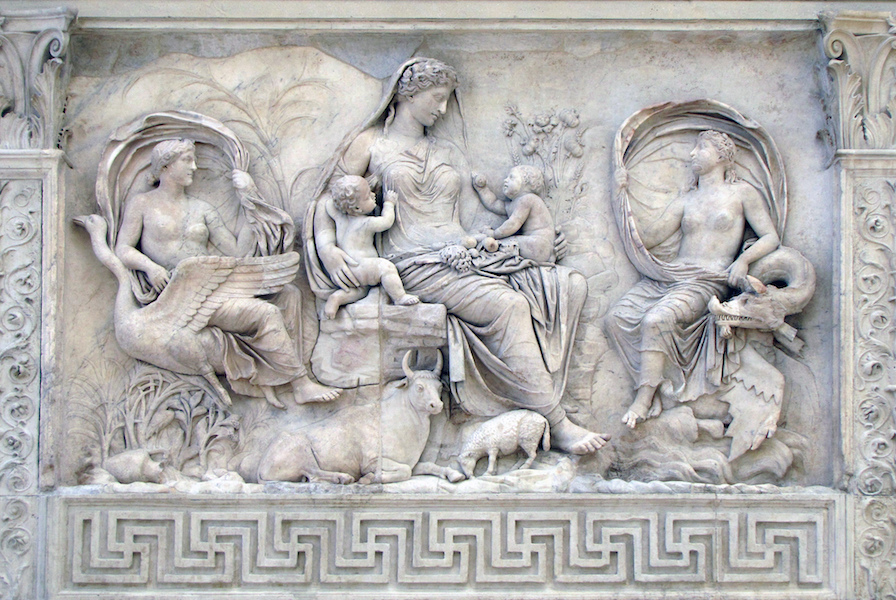

The better preserved panel of the east wall depicts a seated female figure (above) who has been variously interpreted as Tellus (the Earth), Italia (Italy), Pax (Peace), as well as Venus. The panel depicts a scene of human fertility and natural abundance. Two babies sit on the lap of the seated female, tugging at her drapery. Surrounding the central female is the natural abundance of the lands and flanking her are the personifications of the land and sea breezes. In all, whether the goddess is taken as Tellus or Pax, the theme stressed is the harmony and abundance of Italy, a theme central to Augustus’ message of a restored peaceful state for the Roman people—the Pax Romana.

The Altar

The altar itself (below) sits within the sculpted precinct wall. It is framed by sculpted architectural mouldings with crouching gryphons surmounted by volutes flanking the altar. The altar was the functional portion of the monument, the place where blood sacrifice and/or burnt offerings would be presented to the gods.

Implications and interpretation

The implications of the Ara Pacis are far reaching. Originally located along the Via Lata (now Rome’s Via del Corso), the altar is part of a monumental architectural makeover of Rome’s Campus Martius carried out by Augustus and his family. Initially the makeover had a dynastic tone, with the Mausoleum of Augustus near the river. The dedication of the Horologium (sundial) of Augustus and the Ara Pacis, the Augustan makeover served as a potent, visual reminder of Augustus’ success to the people of Rome. The choice to celebrate peace and the attendant prosperity in some ways breaks with the tradition of explicitly triumphal monuments that advertise success in war and victories won on the battlefield. By championing peace—at least in the guise of public monuments—Augustus promoted a powerful and effective campaign of political message making.

Rediscovery

The first fragments of the Ara Pacis emerged in 1568 beneath Rome’s Palazzo Chigi near the basilica of San Lorenzo in Lucina. These initial fragments came to be dispersed among various museums, including the Villa Medici, the Vatican Museums, the Louvre, and the Uffizi. It was not until 1859 that further fragments of the Ara Pacis emerged. The German art historian Friedrich von Duhn of the University of Heidelberg is credited with the discovery that the fragments corresponded to the altar mentioned in Augustus’ Res Gestae. Although von Duhn reached this conclusion by 1881, excavations were not resumed until 1903, at which time the total number of recovered fragments reached 53, after which the excavation was again halted due to difficult conditions. Work at the site began again in February 1937 when advanced technology was used to freeze approximately 70 cubic meters of soil to allow for the extraction of the remaining fragments. This excavation was mandated by the order of the Italian government of Benito Mussolini and his planned jubilee in 1938 that was designed to commemorate the 2,000th anniversary of Augustus’ birth.

Mussolini and Augustus

The revival of the glory of ancient Rome was central to the propaganda of the Fascist regime in Italy during the 1930s. Benito Mussolini himself cultivated a connection with the personage of Augustus and claimed his actions were aimed at furthering the continuity of the Roman Empire. Art, architecture, and iconography played a key role in this propagandistic “revival”. Following the 1937 retrieval of additional fragments of the altar, Mussolini directed architect Vittorio Ballio Morpurgo to construct an enclosure for the restored altar adjacent to the ruins of the Mausoleum of Augustus near the Tiber river, creating a key complex for Fascist propaganda. Newly built Fascist palaces, bearing Fascist propaganda, flank the space dubbed “Piazza Augusto Imperatore” (“Plaza of the emperor Augustus”). The famous Res Gestae Divi Augusti (“Deeds of the Divine Augustus”) was re-created on the wall of the altar’s pavilion. The concomitant effect was meant to lead the viewer to associate Mussolini’s accomplishments with those of Augustus himself.

The Ara Pacis and Richard Meier

The firm of architect Richard Meier was engaged to design and execute a new and improved pavilion to house the Ara Pacis and to integrate the altar with a planned pedestrian area surrounding the adjacent Mausoleum of Augustus.

Between 1995 and the dedication of te new pavilion in 2006 Meier crafted the modernist pavilion that capitalizes on glass curtain walls granting visitors views of the Tiber river and the mausoleum while they perambulate in the museum space focused on the altar itself. The Meier pavilion has not been well-received, with some critics immediately panning it and some Italian politicians declaring that it should be dismantled. The museum has also been the victim of targeted vandalism.

Enduring monumentality

The Ara Pacis Augustae continues to engage us and to incite controversy. As a monument that is the product of a carefully constructed ideological program, it is highly charged with socio-cultural energy that speaks to us about the ordering of the Roman world and its society—the very Roman universe.

Augustus had a strong interest in reshaping the Roman world (with him as the sole leader), but had to be cautious about how radical those changes seemed to the Roman populace. While he defeated enemies, both foreign and domestic, he was concerned about being perceived as too authoritarian–he did not wish to labeled as a king (rex) for fear that this would be too much for the Roman people to accept. So the Augustan scheme involved a declaration that Rome’s republican government had been “restored” by Augustus and he styled himself as the leading citizen of the republic (princeps). These political and ideological motives then influence and guide the creation of his program of monumental art and architecture. These monumental forms, of which the Ara Pacis is a prime example, served to both create and reinforce these Augustan messages.

The story of the Ara Pacis become even more complicated since it is an artifact that then was placed in the service of ideas in the modern age. This results in its identity being impossibly, a mixture of Classicism and Fascism and modernism—all difficult to interpret in a postmodern reality. It is important t

o remember that the sculptural reliefs were created in the first place to be easily readable, so that the viewer could understand the messages of Augustus and his circle without the need to read elaborate texts. Augustus pioneered the use of such ideological messages that relied on clear iconography to get their message across. A great deal was at stake for Augustus and it seems, by virtue of history, that the political choices he made proved prudent. The messages of the Pax Romana, of a restored state, and of Augustus as a leading republican citizen, are all part of an effective and carefully constructed veneer. What was the Pax Romana?

Additional resources:

Ara Pacis Augustae (Reed College)

Roma Sparita Photo Archive (Italian)

Ara Pacis Museum / Richard Meier & Partners Architects

David Castriota, The Ara Pacis Augustae and the Imagery of Abundance in Later Greek and Early Roman Imperial Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

Diane A. Conlin, The Artists of the Ara Pacis: the Process of Hellenization in Roman Relief Sculpture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997).

Nancy de Grummond, “Pax Augusta and the Horae on the Ara Pacis Augustae,” American Journal of Archaeology 94.4 (1990) pp. 663–677.

Karl Galinksy, Augustan Culture: an Interpretive Introduction (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996).

Karl Galinksy ed., The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Peter Heslin, “Augustus, Domitian and the So-called Horologium Augusti,” Journal of Roman Studies, 97 (2007), pp. 1-20.

P. J. Holliday, “Time, History, and Ritual on the Ara Pacis Augustae,” The Art Bulletin 72.4 (December 1990), pp. 542–557.

Paul Jacobs and Diane Conlin, Campus Martius: the Field of Mars in the Life of Ancient Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Diana E. E. Kleiner, Roman Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

Gerhard M. Koeppel, “The Grand Pictorial Tradition of Roman Historical Representation during the Early Empire,” Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II.12.1 (1982), pp. 507-535.

Gerhard M. Koeppel, “The Role of Pictorial Models in the Creation of the Historical Relief during the Age of Augustus,” in The Age of Augustus, edited by R. Winkes (Providence, R.I.: Center for Old World Archaeology and Art, Brown University; Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium: Institut Supérieur d’Archéologie de d’Histoire de l’Art, Collège Érasme, 1985), pp. 89-106.

Paul Rehak, “Aeneas or Numa? Rethinking the Meaning of the Ara Pacis Augustae,” The Art Bulletin 83.2 (Jun., 2001), pp. 190-208.

Paul Rehak, Imperium and Cosmos. Augustus and the Northern Campus Martius, edited by John G. Younger. (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2006).

Alan Riding, “Richard Meier’s New Home for the Ara Pacis, a Roman Treasure, Opens,” The New York Times April 24, 2006.

John Seabrook, “Roman Renovation,” The New Yorker, May 2, 2005 pp. 56-65.

J. Sieveking, “Zur Ara Pacis,” Jahresheft des Österreichischen Archeologischen Institut 10 (1907).

Catherine Slessor, “Roman Remains,” Architectural Review, 219.1307 (2006), pp. 18-19.

M. J. Strazzulla, “War and Peace: Housing the Ara Pacis in the Eternal City,” American Journal of Archaeology 113.2 (2009) pp. 1-10.

Stefan Weinstock, “Pax and the ‘Ara Pacis’,” The Journal of Roman Studies 50.1-2 (1960) pp. 44–58.

Rolf Winkes ed., The age of Augustus: interdisciplinary conference held at Brown University, April 30-May 2, 1982 (Providence, R.I.: Center for Old World Archaeology and Art, Brown University; Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium: Institut Supérieur d’Archéologie de d’Histoire de l’Art, Collège Érasme, 1985).

Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, trans. D. Schneider (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1987).

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Gemma Augustea

by JULIA FISCHER

Upper register, Dioskourides, Gemma Augustea, 9 – 12 C.E., 19 x 23 cm, double-layered sardonyx with gold, gold-plated silver (Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna)

When you think of Roman art, the Colosseum and the ruins of the Roman Forum immediately spring to mind. You may also think of all the public sculpture that decorated ancient Rome, such as the portrait of Augustus from Primaporta (left) or the Ara Pacis Augustae. These public works of art functioned as political propaganda and advertised to all Romans the accomplishments of the emperor. In public art Augustus wanted to promote that he was a military victor, that he brought peace to the Roman Empire, and that he was connected to the gods.

Private art

But the emperor also commissioned small private works of art such as gems, and cameos. Unlike art in the public sphere, private art would not have been seen by a large audience. Instead, only a select few would have been granted access. If you were lucky enough to be invited to a dinner party at the emperor’s palace, he might display his gem collection or show off his large imperial cameos. However, despite the fact that private art would not have been seen by the majority of Roman citizens, the messages contained within these works would have functioned in much the same way as their public counterparts. So if you were at that dinner party with Augustus and he showed you a large cameo, that cameo would have advertised the emperor’s military victories, his role as the bringer of peace, and his connection to the gods.

Cameos were a popular medium in the private art of the Roman Empire. While cameos first appeared in the Hellenistic period, they became most fashionable under the Romans. Typically cameos were made of a brown stone that had bands or layers of white throughout, such as sardonyx. This layered stone was then carved in such a way that the figures stood out in white relief while the background remained the dark part of the stone. Most cameos were small and functioned as pendants or rings. But there are a few examples of much larger cameos that were specifically commissioned by the emperor and members of his imperial circle, the most famous example is the Gemma Augustea.

Gemma Augustea

The Gemma Augustea is divided into two registers that are crammed with figures and iconography. The upper register contains three historical figures and a host of deities and personifications. Our eyes immediately gravitate towards the center of the upper register and the two large enthroned figures, Roma (the personification of the city of Rome) and the emperor Augustus.

Roma is surrounded by military paraphernalia while Augustus holds a scepter, a symbol of his right to rule and his role as the leader of the Roman Empire. At his feet is an eagle, a symbol of the god Jupiter and so we quickly realize that Augustus has close ties to the gods. Augustus is depicted as a heroic semi-nude, a convention usually reserved for deities. Augustus is not only stating that he has connections to gods, he is stating that he is also god-like.

Two other historical figures accompany Augustus in the upper register. At the far left is Tiberius, who will eventually succeed Augustus on the throne. To the right of Tiberius, standing in front of a chariot, is the young Germanicus, another member of Augustus’ family and a potential heir to the throne. Clearly the Gemma Augustea is making Augustus’ dynastic message clear: he hopes that Tiberius or Germanicus will succeed him after he dies.

Interspersed amongst the three historical figures of the upper register are deities and personifications. Directly behind Tiberius is winged Victory. Behind Augustus is Oikoumene, the personification of the civilized world, who places a corona civica (civic crown) on the emperor’s head. In the Roman Empire, it was a great honor to be awarded the civic crown as it was only given to someone who had saved Roman citizens from an enemy (and Augustus had certainly done just that by rescuing Romans from civil war). Oceanus, the personification of the oceans, sits on the far right. Finally, Tellus Italiae, the mother earth goddess and personification of Italy, sits with her two chubby children and holds a cornucopia.

Pax Romana

What does the top register mean, with its grouping of mortals, deities, and personifications? In short, everything praises Augustus. The emperor expresses his domination throughout the Roman Empire and his greatest accomplishment, the pacification of the Roman world, which resulted in fertility and prosperity. Augustus’ peace and dominion will spread not only throughout the city of Rome (represented by the goddess Roma), but also to all of Italy (represented by Tellus Italiae) and throughout the entire civilized world (symbolized by Oikoumene). And as to Tiberius and Germanicus, Augustus’ potential heirs, either will continue the peace and prosperity established by Augustus.

The lower register is significantly smaller than the upper, but it nevertheless has plenty of figures in its two scenes, both of which show captive barbarians and victorious Romans. At the left, Roman soldiers raise a trophy while degraded and humiliated barbarians sit at their feet. At the right is a similar scene, with barbarians being brought into submission by Roman soldiers. While the upper register focuses on peace, the lower register represents the wars that established and maintained peace throughout the Roman Empire.

So even though the Gemma Augustea is a work of private art, the cameo nevertheless offers a political message and thus serves a purpose similar to public art. The Gemma proclaimed Augustus’s greatest accomplishment, the Pax Romana, his military victories, his connections to the gods and his god-like status, and his hopes for dynastic succession.

Additional resources:

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

The art of gem carving

Watch a modern artist engrave a precious gemstone using the techniques of the ancients.

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Video from the J. Paul Getty Museum

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Preparations for a Sacrifice

Animal sacrifice played an important role in ancient Roman religion, but what was involved in the preparation?

An animal sacrifice

The scene depicts a group of four males and a bull preparing for a sacrifice. The bull, bedecked in finery—including its pelta-shaped frontalia—is the intended victim. One attendant (a tibicen) provides music by playing the flute (tibia), two others hold the bull, and the fourth is perhaps the officiant who will conduct the ceremony. The latter figure, wearing a toga, stands at the viewer’s far left, looking toward the sacrificing priests.

Public sacrifices such as the one depicted in this relief played a major role in the Roman state religion. The animal sacrifice itself served multiple functions, chief among them honoring the divinity in question, but also providing a context within which ritual communal feasting could take place after the event. These communal feasts provided valuable nutrition to city dwellers and served to reinforce community ties within the locus of the sanctuary.

The scene is set against a sculpted background that depicts a Corinthian temple (to the left) and a distyle building (to the right) that has two Aeolian capitals flanking a double door; this latter façade is decorated with a laurel garland.

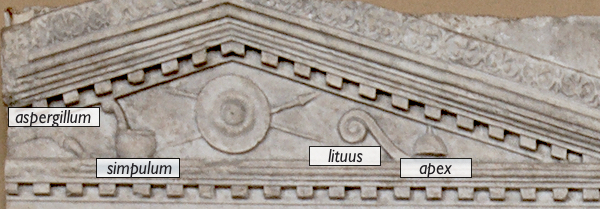

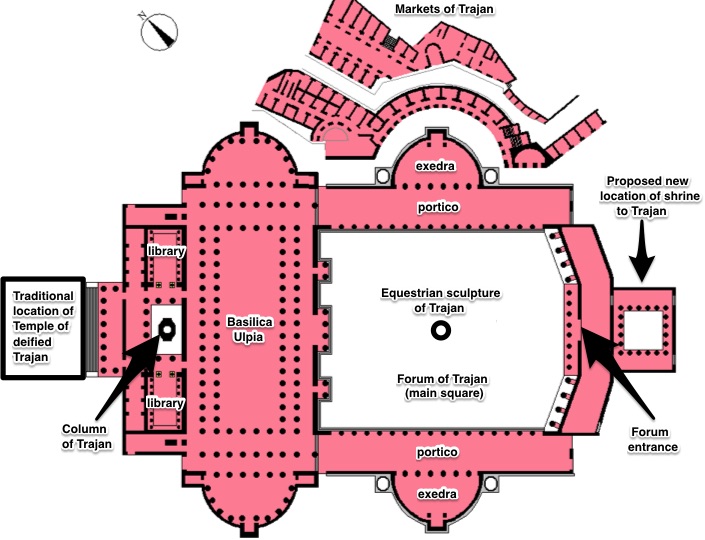

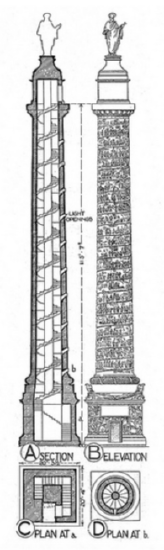

The temple’s pediment (see image below) includes depictions of various Roman ritual equipment including the aspergillum (for sprinkling sacred water), simpulum (a ritual ladle for libations), lituus (the curved wand of a religious official known as an augur), and an apex (a flamen’s hat). Such a background serves not only to situate the main scene but also to add realism and contextualization to these activities as they took place within the city of Rome.