2.10: Ancient Rome III

- Page ID

- 64975

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Middle Empire

By the time of the emperor Trajan, the Roman empire encompassed the whole of the Mediterranean, Britain, much of northern and central Europe and the Near East.

117 - 235 C.E.

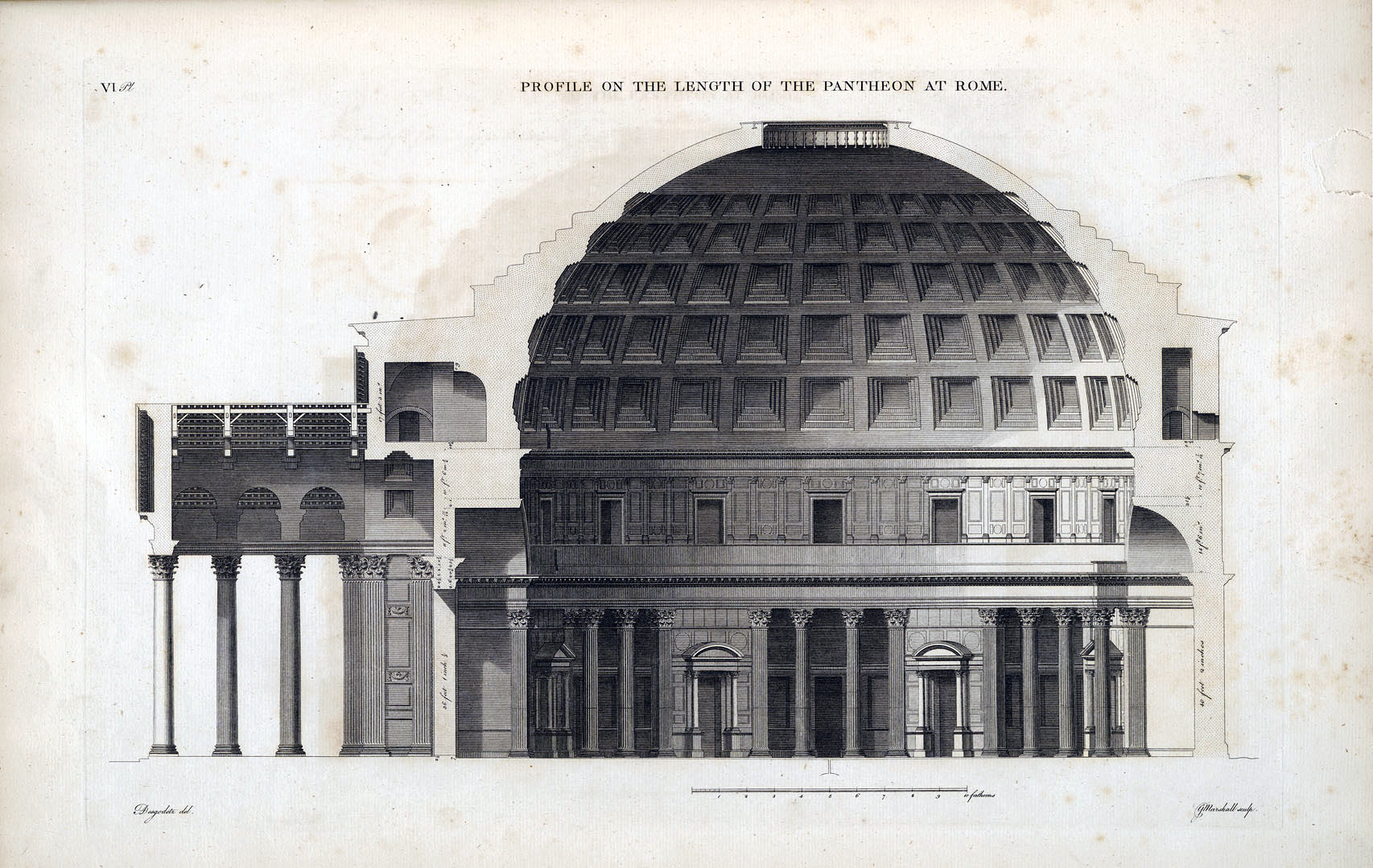

The Pantheon (Rome)

The Pantheon has one of the most perfect interior spaces ever constructed—and it’s been copied ever since.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): The Pantheon, Rome, c. 125

The eighth wonder of the ancient world

The Pantheon in Rome is a true architectural wonder. Described as the “sphinx of the Campus Martius”—referring to enigmas presented by its appearance and history, and to the location in Rome where it was built—to visit it today is to be almost transported back to the Roman Empire itself. The Roman Pantheon probably doesn’t make popular shortlists of the world’s architectural icons, but it should: it is one of the most imitated buildings in history. For a good example, look at the library Thomas Jefferson designed for the University of Virginia.

While the Pantheon’s importance is undeniable, there is a lot that is unknown. With new evidence and fresh interpretations coming to light in recent years, questions once thought settled have been reopened. Most textbooks and websites confidently date the building to the Emperor Hadrian’s reign and describe its purpose as a temple to all the gods (from the Greek, pan = all, theos = gods), but some scholars now argue that these details are wrong and that our knowledge of other aspects of the building’s origin, construction, and meaning is less certain than we had thought.

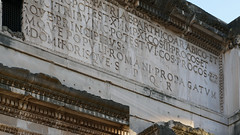

Whose Pantheon?—the problem of the inscription

Archaeologists and art historians value inscriptions on ancient monuments because these can provide information about patronage, dating, and purpose that is otherwise difficult to come by. In the case of the Pantheon, however, the inscription on the frieze—in raised bronze letters (modern replacements)—easily deceives, as it did for many centuries. It identifies, in abbreviated Latin, the Roman general and consul (the highest elected official of the Roman Republic) Marcus Agrippa (who lived in the first century B.C.E.) as the patron: “M[arcus] Agrippa L[ucii] F[ilius] Co[n]s[ul] Tertium Fecit” (“Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, thrice Consul, built this”). The inscription was taken at face value until 1892, when a well-documented interpretation of stamped bricks found in and around the building showed that the Pantheon standing today was a rebuilding of an earlier structure, and that it was a product of Emperor Hadrian’s ( who ruled from 117-138 C.E.) patronage, built between about 118 and 128. Thus, Agrippa could not have been the patron of the present building. Why, then, is his name so prominent?

The conventional understanding of the Pantheon

A traditional rectangular temple, first built by Agrippa

The conventional understanding of the Pantheon’s genesis, which held from 1892 until very recently, goes something like this. Agrippa built the original Pantheon in honor of his and Augustus’ military victory at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E.—one of the defining moments in the establishment of the Roman Empire (Augustus would go on to become the first Emperor of Rome). It was thought that Agrippa’s Pantheon had been small and conventional: a Greek-style temple, rectangular in plan. Written sources suggest the building was damaged by fire around 80 C.E. and restored to some unknown extent under the orders of Emperor Domitian (who ruled 81-96 C.E.).

When the building was more substantially damaged by fire again in 110 C.E., the Emperor Trajan decided to rebuild it, but only partial groundwork was carried out before his death. Trajan’s successor, Hadrian—a great patron of architecture and revered as one of the most effective Roman emperors—conceived and possibly even designed the new building with the help of dedicated architects. It was to be a triumphant display of his will and beneficence. He was thought to have abandoned the idea of simply reconstructing Agrippa’s temple, deciding instead to create a much larger and more impressive structure. And, in an act of pious humility meant to put him in the favor of the gods and to honor his illustrious predecessors, Hadrian installed the false inscription attributing the new building to the long-dead Agrippa.

New evidence—Agrippa’s temple was not rectangular at all

Today, we know that many parts of this story are either unlikely or demonstrably false. It is now clear from archaeological studies that Agrippa’s original building was not a small rectangular temple, but contained the distinctive hallmarks of the current building: a portico with tall columns and pediment and a rotunda (circular hall) behind it, in similar dimensions to the current building.

And the temple may be Trajan’s (not Hadrian’s)

More startling, a reconsideration of the evidence of the bricks used in the building’s construction—some of which were stamped with identifying marks that can be used to establish the date of manufacture—shows that almost all of them date from the 110s, during the time of Trajan. Instead of the great triumph of Hadrianic design, the Pantheon should more rightly be seen as the final architectural glory of the Emperor Trajan’s reign: substantially designed and rebuilt beginning around 114, with some preparatory work on the building site perhaps starting right after the fire of 110, and finished under Hadrian sometime between 125 and 128.

Lise Hetland, the archaeologist who first made this argument in 2007 (building on an earlier attribution to Trajan by Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer), writes that the long-standing effort to make the physical evidence fit a dating entirely within Hadrian’s time shows “the illogicality of the sometimes almost surgically clear-cut presentation of Roman buildings according to the sequence of emperors.” The case of the Pantheon confirms a general art-historical lesson: style categories and historical periodizations (in other words, our understanding of the style of architecture during a particular emperor’s reign) should be seen as conveniences—subordinate to the priority of evidence.

What was it—a temple? A dynastic sanctuary?

It is now an open question whether the building was ever a temple to all the gods, as its traditional name has long suggested to interpreters. Pantheon, or Pantheum in Latin, was more of a nickname than a formal title. One of the major written sources about the building’s origin is the Roman History by Cassius Dio, a late second- to early third-century historian who was twice Roman consul. His account, written a century after the Pantheon was completed, must be taken skeptically. However, he provides important evidence about the building’s purpose. He wrote,

He [Agrippa] completed the building called the Pantheon. It has this name, perhaps because it received among the images which decorated it the statues of many gods, including Mars and Venus; but my own opinion of the name is that, because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens. Agrippa, for his part, wished to place a statue of Augustus there also and to bestow upon him the honor of having the structure named after him; but when Augustus wouldn’t accept either honor, he [Agrippa] placed in the temple itself a statue of the former [Julius] Caesar and in the ante-room statues of Augustus and himself. This was done not out of any rivalry or ambition on Agrippa’s part to make himself equal to Augustus, but from his hearty loyalty to him and his constant zeal for the public good.

A number of scholars have now suggested that the original Pantheon was not a temple in the usual sense of a god’s dwelling place. Instead, it may have been intended as a dynastic sanctuary, part of a ruler cult emerging around Augustus, with the original dedication being to Julius Caesar, the progenitor of the family line of Augustus and Agrippa and a revered ancestor who had been the first Roman deified by the Senate. Adding to the plausibility of this view is the fact that the site had sacred associations—tradition stating that it was the location of the apotheosis, or raising up to the heavens, of Romulus, Rome’s mythic founder. Even more, the Pantheon was also aligned on axis, across a long stretch of open fields called the Campus Martius, with Augustus’ mausoleum, completed just a few years before the Pantheon. Agrippa’s building, then, was redolent with suggestions of the alliance of the gods and the rulers of Rome during a time when new religious ideas about ruler cults were taking shape.

The dome and the divine authority of the emperors

By the fourth century C.E., when the historian Ammianus Marcellinus mentioned the Pantheon in his history of imperial Rome, statues of the Roman emperors occupied the rotunda’s niches. In Agrippa’s Pantheon these spaces had been filled by statues of the gods. We also know that Hadrian held court in the Pantheon. Whatever its original purposes, the Pantheon by the time of Trajan and Hadrian was primarily associated with the power of the emperors and their divine authority.

The symbolism of the great dome adds weight to this interpretation. The dome’s coffers (inset panels) are divided into 28 sections, equaling the number of large columns below. 28 is a “perfect number,” a whole number whose summed factors equal it (thus, 1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14 = 28). Only four perfect numbers were known in antiquity (6, 28, 496, and 8128) and they were sometimes held—for instance, by Pythagoras and his followers—to have mystical, religious meaning in connection with the cosmos. Additionally, the oculus (open window) at the top of the dome was the interior’s only source of direct light. The sunbeam streaming through the oculus traced an ever-changing daily path across the wall and floor of the rotunda. Perhaps, then, the sunbeam marked solar and lunar events, or simply time. The idea fits nicely with Dio’s understanding of the dome as the canopy of the heavens and, by extension, of the rotunda itself as a microcosm of the Roman world beneath the starry heavens, with the emperor presiding over it all, ensuring the right order of the world.

How was it designed and built?

The Pantheon’s basic design is simple and powerful. A portico with free-standing columns is attached to a domed rotunda. In between, to help transition between the rectilinear portico and the round rotunda is an element generally described in English as the intermediate block. This piece is itself interesting for the fact that visible on its face above the portico’s pediment is another shallow pediment. This may be evidence that the portico was intended to be taller than it is (50 Roman feet instead of the actual 40 feet). Perhaps the taller columns, presumably ordered from a quarry in Egypt, never made it to the building site (for reasons unknown), necessitating the substitution of smaller columns, thus reducing the height of the portico.

The Pantheon’s great interior spectacle—its enormous scale, the geometric clarity of the circle-in-square pavement pattern and the dome’s half-sphere, and the moving disc of light—is all the more breathtaking for the way one moves from the bustling square (piazza, in Italian) outside into the grandeur inside.

One approaches the Pantheon through the portico with its tall, monolithic Corinthian columns of Egyptian granite. Originally, the approach would have been framed and directed by the long walls of a courtyard or forecourt in front of the building, and a set of stairs, now submerged under the piazza, leading up to the portico. Walking beneath the giant columns, the outside light starts to dim. As you pass through the enormous portal with its bronze doors, you enter the rotunda, where your eyes are swept up toward the oculus.

The structure itself is an important example of advanced Roman engineering. Its walls are made from brick-faced concrete—an innovation widely used in Rome’s major buildings and infrastructure, such as aqueducts—and are lightened with relieving arches and vaults built into the wall mass. The concrete easily allowed for spaces to be carved out of the wall’s thickness—for instance, the alcoves around the rotunda’s perimeter and the large apse directly across from the entrance (where Hadrian would have sat to hold court). Further, the concrete of the dome is graded into six layers with a mixture of scoria, a low-density, lightweight volcanic rock, at the top. From top to bottom, the structure of the Pantheon was fine-tuned to be structurally efficient and to allow flexibility of design.

Who designed the Pantheon?

We do not know who designed the Pantheon, but Apollodorus of Damascus, Trajan’s favorite builder, is a likely candidate—or, perhaps, someone closely associated with Apollodorus. He had designed Trajan’s Forum and at least two other major projects in Rome, probably making him the person in the capital city with the deepest knowledge about complex architecture and engineering in the 110s. On that basis, and with some stylistic and design similarities between the Pantheon and his known projects, Apollodorus’ authorship of the building is a significant possibility.

When it was believed that Hadrian had fully overseen the Pantheon’s design, doubt was cast on the possibility of Apollodorus’ role because, according to Dio, Hadrian had banished and then executed the architect for having spoken ill of the emperor’s talents. Many historians now doubt Dio’s account. Although the evidence is circumstantial, a number of obstacles to Apollodorus’ authorship have been removed by the recent developments in our understanding of the Pantheon’s genesis. In the end, however, we cannot say for certain who designed the Pantheon.

Why Has It Survived?

We know very little about what happened to the Pantheon between the time of Emperor Constantine in the early fourth century and the early seventh century—a period when the city of Rome’s importance faded and the Roman Empire disintegrated. This was presumably the time when much of the Pantheon’s surroundings—the forecourt and all adjacent buildings—fell into serious disrepair and were demolished and replaced. How and why the Pantheon emerged from those difficult centuries is hard to say. The Liber Pontificalis—a medieval manuscript containing not-always-reliable biographies of the popes—tells us that in the 7th century Pope Boniface IV “asked the [Byzantine] emperor Phocas for the temple called the Pantheon, and in it he made the church of the ever-virgin Holy Mary and all the martyrs.” There is continuing debate about when the Christian consecration of the Pantheon happened; today, the balance of evidence points to May 13, 613. In later centuries, the building was known as Sanctae Mariae Rotundae (Saint Mary of the Rotunda). Whatever the precise date of its consecration, the fact that the Pantheon became a church—specifically, a station church, where the pope would hold special masses during Lent, the period leading up to Easter—meant that it was in continuous use, ensuring its survival.

Yet, like other ancient remains in Rome, the Pantheon was for centuries a source of materials for new buildings and other purposes—including the making of cannons and weapons. In addition to the loss of original finishings, sculpture, and all of its bronze elements, many other changes were made to the building from the fourth century to today. Among the most important: the three easternmost columns of the portico were replaced in the seventeenth century after having been damaged and braced by a brick wall centuries earlier; doors and steps leading down into the portico were erected after the grade of the surrounding piazza had risen over time; inside the rotunda, columns made from imperial red porphyry—a rare, expensive stone from Egypt—were replaced with granite versions; and roof tiles and other elements were periodically removed or replaced. Despite all the losses and alterations, and all the unanswered and difficult questions, the Pantheon is an unrivalled artifact of Roman antiquity.

Additional Resources:

Mary T. Boatwright, “Hadrian and the Agrippa Inscription of the Pantheon,” in Hadrian: Art, Politics and Economy, edited by Thorsten Opper (London: British Museum, 2013), pp. 19-30.

Paul Godfrey and David Hemsoll. “The Pantheon: Temple or Rotunda?” in Pagan Gods and Shrines of the Roman Empire, edited by Martin Henig and Anthony King (Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology, 1986), pp. 195-209.

Gerd Graßhoff, Michael Heinzelmann, and Markus Wäfler, editors, The Pantheon in Rome: Contributions (Bern: Bern Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science, 2009)

Robert Hannah and Giulio Magli. “The Role of the Sun in the Pantheon’s Design and Meaning,” Numen 58 (2011), pp. 486-513.

Lise M. Hetland, “Dating the Pantheon,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 20 (2007), pp. 95-112.

Mark Wilson Jones, Principles of Roman Architecture (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000)

Tod A Marder and Mark Wilson Jones, editors, The Pantheon from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Gene Waddell, Creating the Pantheon: Design, Materials, and Construction (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2008)

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Bronze head from a statue of the Emperor Hadrian

Hadrian (reigned 117-138 C.E.), once a tribune (staff officer) in three different legions of the Roman army and commander of a legion in one of Trajan’s wars, was often shown in military uniform. He was clearly keen to project the image of an ever-ready soldier, but other conclusions have been drawn from his surviving statues.

Fixing the Empire’s borders

When Hadrian inherited the Roman Empire, his predecessor, Trajan’s military campaigns had over-stretched it. Rebellions against Roman rule raged in several provinces and the empire was in serious danger. He ruthlessly put down rebellions and strengthened his borders. He built defensive barriers in Germany and Northern Africa.

Rome’s first emperor, Augustus (reigned 27 B.C.E.– 14 C.E.), had also suffered severe military setbacks, and took the decision to stop expanding the empire. In Hadrian’s early reign Augustus was an important role model. He had a portrait of him on his signet ring and kept a small bronze bust of him among the images of the household gods in his bedroom.

Like Augustus before him, Hadrian began to fix the limits of the territory that Rome could control. He withdrew his army from Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq, where a serious insurgency had broken out, and abandoned the newly conquered provinces of Armenia and Assyria, as well as other parts of the empire.

Hadrian’s travels

Hadrian is also famous as the emperor who built the eighty-mile-long wall across Britain, from the Solway Firth to the River Tyne at Wallsend: “to separate the barbarians from the Romans” in the words of his biographer. This head comes from a statue of Hadrian that probably stood in Roman London in a public space such as a forum. It would have been one and a quarter times life-size.

This statue may have been put up to commemorate Hadrian’s visit to Britain in 122 C.E.; Hadrian travelled very extensively throughout the Empire, and imperial visits generally gave rise to program of rebuilding and beautification of cities. There are many known marble statues of him, but this example made in bronze is a rare survival.

Born in Rome but of Spanish descent, Hadrian was adopted by the emperor Trajan as his successor. Having served with distinction on the Danube and as governor of Syria, Hadrian never lost his fascination with the empire and its frontiers.

At Tivoli, to the east of Rome, he built an enormous palace, a microcosm of all the different places he had visited. He was an enthusiastic public builder, and perhaps his most celebrated building is the Pantheon, the best preserved Roman building in the world. Hadrian’s Wall is a good example of his devotion to Rome’s frontiers and the boundaries he established were retained for nearly three hundred years.

A lover of culture

Hadrian was the first Roman emperor to wear a full beard. This has usually been seen as a mark of his devotion to Greece and Greek culture.

Hadrian openly displayed his love of Greek culture. Some of the senate scornfully referred to him as Graeculus (“the Greekling”). Beards had been a marker of Greek identity since classical times, whereas a clean-shaven look was considered more Roman. However, in the decades before Hadrian became emperor, beards had come to be worn by wealthy young Romans and seem to have been particularly prevalent in the military. Furthermore, one literary source, the Historia Augusta, claims that Hadrian wore a beard to hide blemishes on his face.

Hadrian fell seriously ill, perhaps with a form of dropsy (swelling caused by excess fluid), and retired to the seaside resort of Baiae on the bay of Naples, where he died in 138 C.E.

The image of the Roman Emperor

The cult of the Emperor combined religious and political elements and was a vital factor in Roman military and civil administration. Deceased rulers were often deified, and though the living Emperor, who was the state’s chief priest, was not himself worshipped as a god, his “numen,” the spirit of his power and authority, was.

The image of the ruler and information about his achievements was spread primarily through coinage. In addition, statues and busts, in stone and bronze and occasionally even precious metal, were placed in a variety of official and public settings. They varied in size: colossal, life-size and smaller. Such images symbolized the power of the state and the essential unity of the Empire.

As well as the political importance of representations of the Emperor, his physical appearance and that of his consort and family were familiar to people throughout the Empire. This influenced fashion and such representations can assist the modern archaeologist and art-historian. For example, beards became fashionable after the accession of Hadrian, and the hairstyles of Empresses and other Imperial women may be seen in private portraiture and decorative art, even in remote provinces such as Britain.

© Trustees of the British Museum

A virtual tour of Hadrian’s Villa

by DR. BERNARD FRISCHER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Explore Hadrian’s Villa in 3D and learn about Hadrian from the emperor himself.

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): A virtual tour of Hadrian’s Villa using a 3D digital model of the villa created under the direction of Dr. Bernard Frischer.

The ruins of Hadrian’s Villa, in the town of Tivoli, near Rome, is spread over an area of approximately 250 acres. Many of the structures were designed by the Emperor Hadrian, who ruled from 117 until his death in 138 C.E. This virtual rendering is based on current archeological research and has been created in consultation with art historians, archaeologists, and museum curators with expertise in this area. Please note that a few features are necessarily assumptions based on the best available evidence.

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Hadrian: The imperial palace, Tivoli

The Empire in miniature, see how Hadrian’s Villa served as a space for both business and pleasure.

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Video from The British Museum.

Maritime Theatre at Hadrian’s Villa

by DR. BERNARD FRISCHER and DR. BETH HARRIS

A lavish Roman house in miniature, explore the innermost sanctum of the emperor Hadrian’s villa.

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Maritime Theatre at Hadrian’s Villa, Tivoli, Villa begun in 117 C.E

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Rome’s layered history — the Castel Sant’Angelo

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): A conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris at the Castel Sant’Angelo (Mausoleum of Hadrian), 139 C.E., Rome

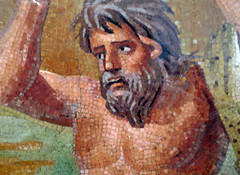

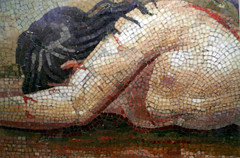

Pair of Centaurs Fighting Cats of Prey from Hadrian’s Villa

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Discover the drama of this split second in time, as a centaur flights big cats for his life.

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Pair of Centaurs Fighting Cats of Prey from Hadrian’s Villa, mosaic, c. 130 C.E. (Altes Museum, Berlin)

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Hadrian: Building the wall

At the remotest point of the Roman Empire, Hadrian erected this fortification—a symbol of control and dominance.

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Video from The British Museum.

Medea Sarcophagus

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

One of the great myths of jealousy and revenge is carved into this sarcophagus. But why put this story on a coffin?

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Medea Sarcophagus, 140 – 150 C.E., marble, 65 x 227 cm (Altes Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

Equestrian Sculpture of Marcus Aurelius

Due to a fortunate case of mistaken identity, this commanding statue was saved from destruction.

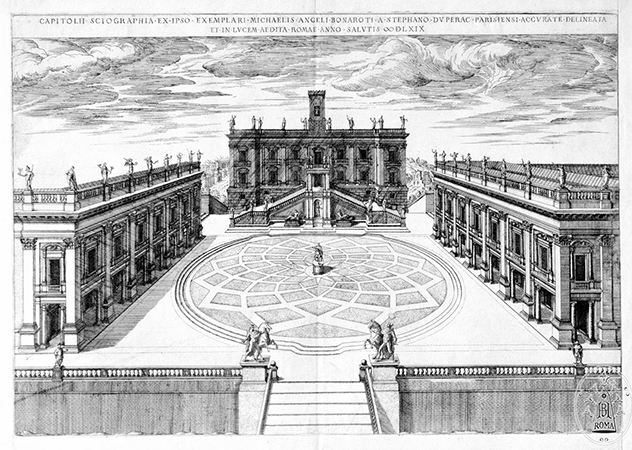

The original location of the sculpture is unknown, though it had been housed in the Lateran Palace since the 8th century until it was placed in the center of the Piazza del Campidoglio by Michelangelo in 1538. The original is now indoors for purposes of conservation. Marcus Aurelius ruled 161-180 C.E.

In ancient Rome equestrian statues of emperors would not have been uncommon sights in the city—late antique sources suggest that at least 22 of these “great horses” (equi magni) were to be seen—as they were official devices for honoring the emperor for singular military and civic achievements. The statues themselves were, in turn, copied in other media, including coins, for even wider distribution.

Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\): Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, c. 173-76 C.E. gilded bronze (Capitoline Museums, Rome). The original location of the sculpture is unknown. Beginning in the 8th century, it was located near the Lateran Palace, until it was placed in the center of the Piazza del Campidoglio in 1538 by Michelangelo. The original statue is now indoors for purposes of conservation (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Few examples of these equestrian statues survive from antiquity, however, making the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius a singular artifact of Roman antiquity, one that has borne quiet witness to the ebb and flow of the city of Rome for nearly 1,900 years. A gilded bronze monument of the 170s C.E. that was originally dedicated to the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, referred to commonly as Marcus Aurelius (reigned 161-180 C.E.), the statue is an important object not only for the study of official Roman portraiture, but also for the consideration of monumental dedications. Further, the use of the statue in the Medieval, Renaissance, modern, and post-modern city of Rome has important implications for the connectivity that exists between the past and the present.

Description

The statue is an over life-size depiction of the emperor elegantly mounted atop his horse while participating in a public ritual or ceremony; the statue stands approximately 4.24 meters tall. A gilded bronze statue, the piece was originally cast using the lost-wax technique, with horse and rider cast in multiple pieces and then soldered together after casting.

The horse

The emperor’s horse is a magnificent example of dynamism captured in the sculptural medium. The horse, caught in motion, raises its right foreleg at the knee while planting its left foreleg on the ground, its motion checked by the application of reins, which the emperor originally held in his left hand. The horse’s body—in particular its musculature—has been modeled very carefully by the artist, resulting in a powerful rendering. In keeping with the motion of the horse’s body, its head turns to its right, with its mouth opened slightly. The horse wears a harness, some elements of which have not survived. The horse is saddled with a Persian-style saddlecloth of several layers, as opposed to a rigid saddle. It should be noted that the horse is an important and expressive element of the overall composition.

The horseman

The horseman sits astride the steed, with his left hand guiding the reins and his right arm raised to shoulder level, the hand outstretched.

There are approximately 110 known portraits of Marcus Aurelius and these have been grouped into four typological groupings. The first two types belong to the emperor’s youth, before he assumed the duties of the principate.

In the Roman world it was standard practice to create official portrait types of high-ranking officials, such as emperors that would then circulate in various media, notably sculpture in the round and coin portraits. These portrait types are vital in several respects, especially for determining the chronology of monuments and coins, since the portrait types can usually be placed in a fairly accurate and legible chronological order.

The interpretation of these portraits relies on various key elements, especially the reading of hairstyle and the examination of facial physiognomy. In the case of the equestrian statue, the portrait typology offers the best means of assigning an approximate date to the object since it does not otherwise offer another means of dating. The earliest portrait of Marcus Aurelius dates to c. 140 C.E. and is best represented by the Capitoline Galleria 28 type, where the youth wears a cloak fastened at the shoulder (paludamentum); this portrait was widely circulated, with approximately 25 known copies (above).

The second portrait type was made when Marcus was in his late 20s, c. 147 C.E. and shows a still youthful type, although Marcus now has light facial hair (below).

Marcus Aurelius became emperor in 161 C.E., when he was forty years of age; this was the occasion for the creation of his third and most important portrait type. This mature type shows the emperor fully bearded with a full head of tightly curled, voluminous hair; he retains the characteristic oval-shaped face and heavy eyelids from his earlier portraits. His coiffure forms a distinctive arc over his forehead. This third type is known from approximately 50 copies.

The emperor’s fourth portrait type (above), created between 170 and 180 C.E., retains most of the features of the third type, but shows the emperor slightly more advanced in age with a very full beard that is divided in the center at the chin, showing parallel locks of hair.

The statue of the horseman is carefully composed by the artist and depicts a figure that is simultaneously dynamic and a bit passive and removed, by virtue of his facial expression (see image below). The locks of hair are curly and compact and distributed evenly; the beard is also curly, covering the cheeks and upper lip, and is worn longer at the chin. The pose of the body shows the rider’s head turned slightly to his right, in the direction of his outstretched right arm. The left hand originally held the reins (no longer preserved) between the index and middle fingers, with the palm facing upwards. Scholars continue to debate whether he originally held some attached figure or object in the palm of the left hand; possible suggestions have included a scepter, a globe, a statue of victory – but there is no clear indication of any attachment point for such an object. On the left hand the rider does wear the senatorial ring.

The rider is clad in civic garb, including a short-sleeved tunic that is gathered at the waist by a knotted belt (cingulum). Over the tunic the rider wears a cloak (paludamentum) that is clasped at the right shoulder. On his feet Marcus Aurelius wears the senatorial boots of the patrician class, known as calcei patricii.

Interpretation and chronology

The interpretation and chronology of the equestrian statue must rely on the statue itself, as no ancient literary testimony or other evidence survives to aid in the interpretation. It is obvious that the statue is part of an elaborate public monument, no doubt commissioned to mark an important occasion in the emperor’s reign. With that said, however, it must also be noted that scholars continue to debate its precise dating, the occasion for its creation, and its likely original location in the city of Rome.

Starting with the portrait typology it is possible to determine a range of likely dates for the statue’s creation. The portrait is clearly an adult type of the emperor, meaning the statue must have been created after 161 C.E., the year of Marcus Aurelius’ accession and the creation of his third portrait type. This provides a terminus post quem (the limit after which) for the equestrian statue. Art historians have debated whether the portrait head most resembles the Type III or the Type IV portrait. Recent scholarly thinking, based on the work of Klaus Fittschen, holds that the equestrian portrait represents a unique variant of the standard Type III portrait, created as an improvisation by the artist who was commissioned to create the equestrian statue. In the end the precise chronology of the portrait head—and indeed the typology—remains a matter of scholarly debate.

The pose of the horseman is also helpful. The emperor stretches his right hand outward, the palm facing toward the ground; a pose that could be interpreted as the posture of adlocutio, indicating that the emperor is about to speak. However, more likely in this case we may read it as the gesture of clemency (clementia), offered to a vanquished enemy, or of restitutio pacis, the “restoration of peace.” Richard Brilliant has noted that since the emperor appears in civic garb as opposed to the general’s armor, the overall impression of the statue is one of peace rather than of the immediate post-war celebration of military victory. Some art historians reconstruct a now-missing barbarian on the right side of the horse, as seen in a surviving panel relief sculpture that originally belonged to a now-lost triumphal arch dedicated to Marcus Aurelius (left). We know that Marcus Aurelius celebrated a triumph in 176 C.E. for his victories over German and Sarmatian tribes, leading some to suggest that year as the occasion for the creation of the equestrian monument.

History

The original location of the equestrian monument also remains debated, with some supporting a location on the Caelian Hill near the barracks of the imperial cavalry (equites singulares), while others favor the Campus Martius (a low-lying alluvial plain of the Tiber River) as a possible location. A text known as the Liber Pontificalis that dates to the middle of the tenth century C.E. mentions the equestrian monument, referring to it as “caballus Constantini” or the “horse of Constantine.” According to the text, the urban prefect of Rome was condemned following an uprising against Pope John XII and, as punishment, was hung by the hair from the equestrian monument. At this time the equestrian statue was located in the Lateran quarter of the city of Rome near the Lateran Palace, where it may have been since at least the eighth century C.E. Popular theories at the time held that the bearded emperor was in fact Constantine I, thus sparing the statue from being melted down.

In 1538 the statue was relocated from the Lateran quarter to the Capitoline Hill to become the centerpiece for Michelangelo’s new design for the Campidoglio (a piazza, or public square, at the top of the Capitoline hill). The statue was set atop a pedestal at the center of an intricately designed piazza flanked by three palazzi (image above). It became the centerpiece of the main piazza of secular Rome and, as such, an icon of the city, a role that its still retains. The equestrian statue still plays a role as an official symbol of the city of Rome, even being incorporated into the reverse image of the Italian version of the € 0.50 coin (image above). The statue itself remained where Michelangelo positioned it until it was moved indoors in 1981 for conservation reasons; a high-tech copy of the original was placed on the pedestal. The ancient statue is now housed within the Musei Capitolini where it can be visited and viewed today.

The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius is an enduring monument, one that links the city’s many phases, ancient and modern. It has borne witness to the city’s imperial glory, post-imperial decline, its Renaissance resurgence, and even its quotidian experience in the twenty-first century. In so doing it reminds us about the role of public art in creating and reinforcing cultural identity as it relates to specific events and locations. In the ancient world the equestrian statue would have evoked powerful memories from the viewer, not only reinforcing the identity and appearance of the emperor but also calling to mind the key events, achievements, and celebrations of his administration. The statue is, like the city, eternal, as reflected by the Romanesco poet Giuseppe Belli who reflects in his sonnet Campidojjo (1830) that the gilded statue is directly linked to the long sweep of Rome’s history.

Additional resources:

Capitoline Museums – Marcus Aurelius Exedra

J. Bergemann, Römische Reiterstatuen: Ehrendenkmäler im öffentlichen Bereich (Mainz am Rhein: Ph. von Zabern, 1990).

A. Birley, Marcus Aurelius: a Biography (London: Routledge, 2002).

P.J.E. Davies, Death and the emperor: Roman imperial funerary monuments, from Augustus to Marcus Aurelius (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004)

P. Fehl, “The Placement of the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius in the Middle Ages.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 37, 1974, pp. 362-67.

K. Fittschen and P. Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts in den Capitolinischen Museen und den anderen kommunalen Sammlungen der Stadt Rom. 3 v. (Berlin: P. von Zabern, 1983-2010).

D. E. E. Kleiner, Roman Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

M. Nimmo, Marco Aurelio, mostra di cantiere: le indagini in corso sul monumento (Rome: Arti grafiche pedanesi, 1984).

C. P. Presicce, and A. M. Sommella, The Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius in Campidoglio (Milan: Silvana, 1990).

I. S. Ryberg, “Rites of the state religion in Roman art” (Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome; 22) (Rome: American Academy in Rome, 1955).

I. S. Ryberg, Panel reliefs of Marcus Aurelius (New York: Archaeological Institute of America, 1967).

K. Stemmer, ed. Kaiser, Marc Aurel und Seine Zeit: Das Römische Reich im Umbruch (Berlin: Abguss-Sammlung Antiker Plastik, 1988).

D. E. Strong, Roman Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976).

A. M. Vaccaro, et al., Marco Aurelio: storia di un monumento e del suo restauro (Milan: Silvana, 1989).

M. van Ackeren, ed., A Companion to Marcus Aurelius (Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012).

The importance of the archaeological findspot: The Lullingstone Busts

by DR. ELIZABETH MARLOWE and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

What do we gain when works come from a well-documented excavation?

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Lullingstone Busts, 2nd century C.E. Speakers: Dr. Elizabeth Marlowe and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources:

Lullingstone Roman Villa (from English Heritage)

G. W. Meates, The Lullingstone Roman Villa, Archaeologia Cantiana, vol. 63 (1950), pp. 1-49.

K. S. Painter, The Lullingstone Wall-Plaster: An Aspect of Christianity in Roman Britain, The British Museum Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 3/4 (Spring, 1969), pp. 131-150.

The Arch of Septimius Severus, portal to ancient Rome

by DR. DARIUS ARYA and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Triumphal Arch of Septimius Severus, 203 C.E., marble above a travertine base, roughly 23 x 25 m, Roman Forum, speakers: Dr. Darius Arya, executive director of the American Institute for Roman Culture and Dr. Beth Harris

The Severan Tondo: damnatio memoriae in ancient Rome

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): A conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris in front of The Severan Tondo, c. 200 C.E., 30.5 cm, tempera on wood (Altes Museum, Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

Additional resources:

Klaus Forschen, The portraits of Roman emperors and their families,” in The Emperor and Rome: Space, Representation, and Ritual, edited by Björn C. Ewald and Carlos F. Noreña (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Eric R. Varner, Mutilation and Transformation : Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture (Brill 2004)

Severan marble plan (Forma Urbis Romae)

This ancient map served as an administrative tool for one of the largest empires in history.

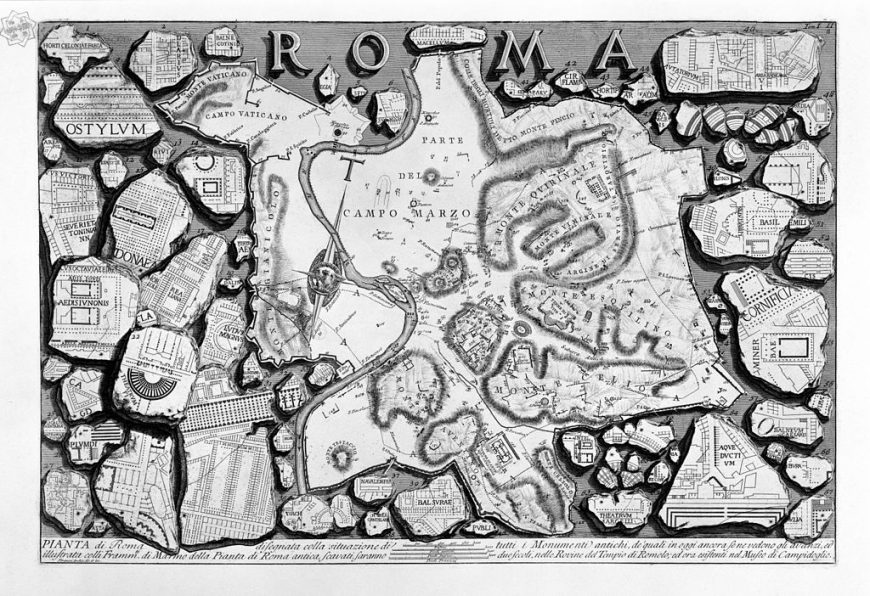

Imagining ancient Rome

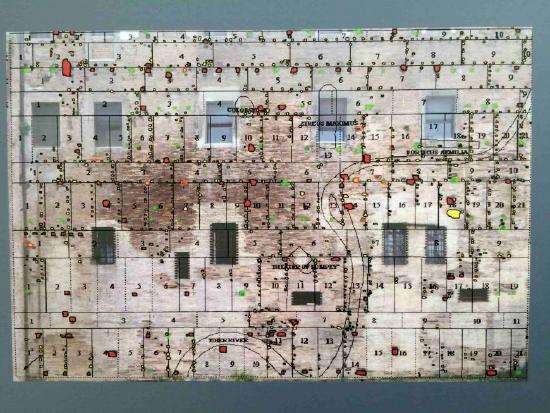

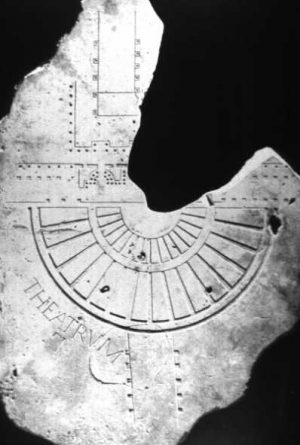

What did the ancient city of Rome look like? What was it like to walk through Rome’s streets? Did the ancient city resemble the Rome that we know today? For centuries, this set of questions occupied the attention of artists and scholars, ranging from engravers like Giovanni Battista Piranesi who produced “views” and a map of the ruined state of ancient Rome (above), to mapmakers like Giambattista Nolli whose famous map of the city was produced in the time of Pope Benedict XIV (1748), to archaeological plans like the Forma Urbis Romae produced by Rodolfo Lanciani at the end of the nineteenth century. One thing that Piranesi, Nolli, and Lanciani had in common was an awareness of the fragmentary remains of a much older depiction of the city’s layout, the so-called “Severan marble plan” that dates to the third century C.E.

The Severan marble plan of Rome (also known as the Forma Urbis Romae) was a carved plan of the city of Rome produced during the first decade of the third century C.E. and mounted on a wall of the Temple of Peace in Rome. Rendered at a scale of approximately 1 to 240, the Severan marble plan was engraved on 150 marble slabs and originally measured approximately 60 by 43 feet (18.1 by 13 meters). The orientation of the map itself would seem at odds with our twenty-first century north-oriented outlook—the Severan marble plan was oriented with south at the top. The plan is a detailed and intricate undertaking, with building layouts shown for the city of Rome—including temples, public buildings, public baths, houses, and the housing blocks (insulae) of the city. Interior details such as columns and staircases are also indicated, and some complexes—particularly notable public ones—are labeled.

Only fragments remain

After antiquity, the marble plan disappeared—the metal clamps that affixed it to the wall were likely robbed and the slabs simply collapsed to the ground. The first recorded rediscovery of the Severan marble plan was in 1562 when Giovanni Antonio Dosio excavated fragments near the sixth-century basilica church of Santi Cosma e Damiano. The basilica incorporates former architectural elements of the ancient Temple of Peace that had originally been built by the emperor Vespasian in the 70s C.E. The fragments were passed between multiple sixteenth-century collectors, but there was little interest in examining them closely at that time. But in 1741, the fragments became property of the city of Rome and were subsequently studied and drawn by scholars and artists, including Piranesi, and research continued throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Additional fragments were discovered in 1999 and others have appeared sporadically since then. In all only approximately 1,186 fragments of the original plan (only about 10-15%) are known to survive.

The conjectural restoration of the fragments (above) suggests that the viewer would have been presented with an urban panorama in plan view, complete with miniscule details. What purpose the plan served, however, remains an open question for scholars. It is likely that the official offices for the government of the city of Rome during the imperial period occupied rooms next to the wall where the marble plan was hung, suggesting that it may have had an official, administrative function. Its scale and location, however, call it into question as a practical, useful object. The marble plan may have served a more representative function, placing it in line with painted and carved landscape views—both fantastical and realistic—known from other examples of Roman art.

Whatever its original use, the marble plan provokes and stimulates the imagination of the viewer: those who have studied the fragments have drawn enormous inspiration from this view of the city. The fragments influenced Lanciani’s creation of his own archaeological map of Rome (Forma Urbis Romae, 1893-1901), which in turn strongly influenced Italo Gismondi and his team as they designed and built the famous model of Rome (Plastico di Roma antica) first exhibited at Rome in 1937 (now in the Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome). Gismondi’s model still strongly influences views of what ancient Rome looked like, revealing a continued interest in the question of how one might imagine the ancient city.

Additional resources:

Gianfilippo Carettoni, Antonio M. Colini, Lucos Cozza, and Guglielmo Gatti, eds. La pianta marmorea di Roma antica. Forma urbis Romae (Rome 1960).

Christian Hülsen. “La rappresentazione degli edifizi Palatini nella ‘Forma Urbis Romae’ dei tempi Severiani.” Dissertazione alla Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia 11 (1914) pp. 101-120.

Robert B. Lloyd, “Three Monumental Gardens on the Marble Plan.” American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 86, No. 1 (Jan., 1982), pp. 91-100.

David West Reynolds, Forma Urbis Romae: The Severan Marble Plan and the Urban Form of Ancient Rome (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Michigan, 1996).

Emilio Rodríguez Almeida, Forma Urbis Marmorea. Aggiornamento Generale 1980 (Rome 1981).

Emilio Rodríguez-Almeida, “A proposito della Forma marmorea e di altre formae.” Mélanges de l’Ecole Française de Rome, Antiquité 112.1 (2000) pp. 217-230. Online at persee.fr

Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project

R. J. A. Talbert, R. W. Unger, eds., Cartography in Antiquity and the Middle Ages: Fresh Perspectives, New Methods (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2008).

Pier Luigi Tucci, “Eight Fragments of the Marble Plan of Rome Shedding New Light on the Transtiberim.” Papers of the British School at Rome Vol. 72 (2004), pp. 185-202.

Pier Luigi Tucci, “New fragments of ancient plans of Rome.” Journal of Roman Archaeology vol. 20 (2007), pp. 469-80.

Battle of the Romans and Barbarians (Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus)

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Romans fight barbarians on this chaotic coffin, which shows signs of a turn in artistic trends.

Late Empire

In the third century C.E. the Ancient Roman Empire was threatened by economic crisis, weak and short-lived emperors and usurpers, and the loss of territory to barbarian invasions.

235 - 410 C.E.

Trebonianus Gallus — emperor or athlete? Rethinking a modern attribution

by DR. ELIZABETH MARLOWE and DR. BETH HARRIS

In the chaos of the 3rd century, can we be sure about the identification of this statue?

Additional resources:

Portraits of the Four Tetrarchs

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Learn how the solid, abstracted forms of these co-emperors reject earlier understanding of the human body.

Video \(\PageIndex{15}\): Portraits of the Four Tetrarchs, from Constantinople, c. 305, porphyry, 4′ 3″ high (St. Marks, Venice)

Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine

by DR. DARIUS ARYA and DR. BETH HARRIS

Built using new technologies, this building is overwhelming and unprecedented—displaying Roman imperial power.

Video \(\PageIndex{16}\): Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine (Basilica Nova), Roman Forum, c. 306-312

The Colossus of Constantine

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Does the abstraction of form and faraway look in this colossal portrait hint at the growth of Christianity in Rome?

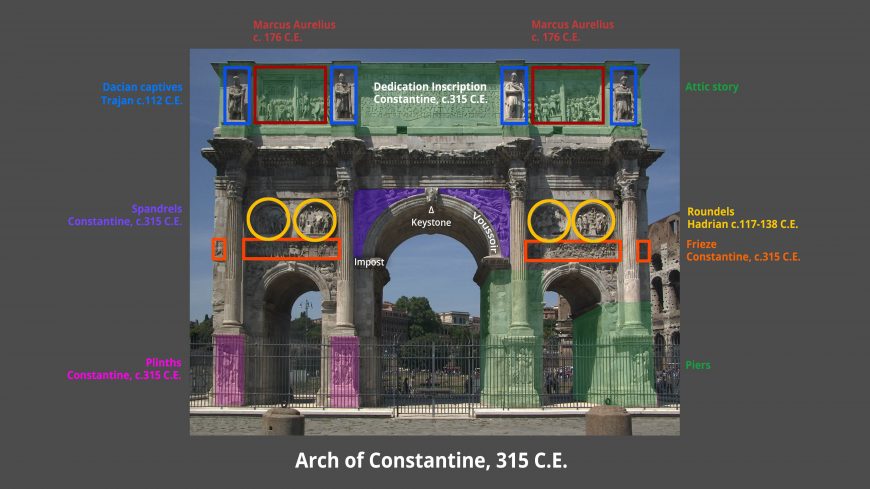

Arch of Constantine, Rome

For the first time, a Roman emperor celebrated victory over fellow Romans, and appropriated the art of earlier rulers.

Video \(\PageIndex{18}\): Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. Video produced by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

The Emperor Constantine, called Constantine the Great, was significant for several reasons. These include his political transformation of the Roman Empire, his support for Christianity, and his founding of Constantinople (modern day Istanbul). Constantine’s status as an agent of change also extended into the realms of art and architecture. The Triumphal Arch of Constantine in Rome is not only a superb example of the ideological and stylistic changes Constantine’s reign brought to art, but also demonstrates the emperor’s careful adherence to traditional forms of Roman Imperial art and architecture.

Location and Appearance

The Arch of Constantine is located along the Via Triumphalis in Rome, and it is situated between the Flavian Amphitheater (better known as the Colosseum) and the Temple of Venus and Roma. This location was significant, as the arch was a highly visible example of connective architecture that linked the area of the Forum Romanum (Roman Forum) to the major entertainment and public bathing complexes of central Rome.

The monumental arch stands approximately 20 meters high, 25 meters wide, and 7 meters deep. Three portals punctuate the exceptional width of the arch, each flanked by partially engaged Corinthian columns. The central opening is approximately 12 meters high, above which are identical inscribed marble panels, one on each side, that read:

To the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantinus, the Greatest,

pious, fortunate, the Senate and people of Rome,

by inspiration of divinity and his own great mind

with his righteous arms

on both the tyrant and his faction

in one instant in rightful

battle he avenged the republic,

dedicated this arch as a memorial to his military victory

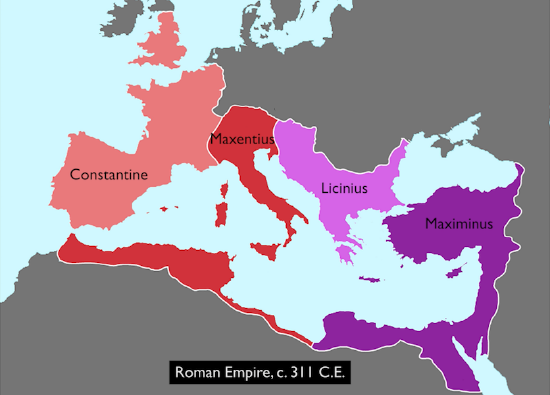

The end of the Tetrarchy

Beginning in the late 3rd century, the Roman Empire was ruled by four co-emperors (two senior emperors and two junior emperors), in an effort to bring political stability after the turbulent 3rd century. But in 312 C.E., Constantine took control over the Western Roman Empire by defeating his co-emperor Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (and soon after became the sole ruler of the empire). The inscription on the arch refers to Maxentius as the tyrant and portrays Constantine as the rightful ruler of the Western Empire. Curiously, the inscription also attributes the victory to Constantine’s “great mind” and the inspiration of a singular divinity. The mention of divine inspiration has been interpreted by some scholars as a coded reference to Constantine’s developing interest in Christian monotheism.

Sculpture from different eras

Perhaps the most striking feature of the Arch is its eclectic and stylistically varied relief sculptures. Some aspects of the sculpture are quite standard, like the Victoria (or Nike) figures that occupy the spandrels above the central archway or the typical architectural moldings found in most imperial Roman public and religious architecture (below).

Other sculpted elements, however, show a multiplicity of styles. In fact, most scholars accept that many of the sculptures of the arch were spolia taken from older monuments dating to the 2nd century C.E. Although there is some scholarly disagreement on the origins of the sculptures, their imperial style corresponds to those of the reigns of Trajan (ruled 98-117 C.E.—the figures surmounting the decorative columns), Hadrian (ruled 117-138 C.E.—the middle register roundels), and Marcus Aurelius (ruled 161-180 C.E.—the large panel reliefs on the top registers). Most of the reliefs feature the emperors participating in codified activities that demonstrate the ruler’s authority and piety by addressing troops, defeating enemies, distributing largesse, and offering sacrifices.

Some sculptural elements of the structure also date to Constantine’s reign, most notably the frieze which is located immediately above the portals. These relief sculptures are of a drastically different style and narrative content when compared with the spoliated (older, borrowed) sections (below, left); Constantine’s relief sculptures (below, right) feature squat and blocky figures that are more abstract than they are naturalistic.

The Constantinian reliefs also depict historical, rather than general events related to Constantine, including his rise to power and victory over Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge. There is also a scene of Constantine distributing largesse (funds) to the public—recalling the scenes of emperors from the earlier sculptures.

Clarity of form

Regarding style, the relief figures from Constantine’s age still seem like outliers. Yet in comparison to the idealized naturalism of the earlier sculptural elements (for example, in the roundels in the image below), the thick, bold outlines of the Constantinian figures render them remarkably legible to passersby. While the Constantinian figures lack natural aesthetics, their clarity of form ensured that they were informative and communicated Constantine’s official (and celebrated) history to viewers of his own time.

Analysis and Meaning

Until relatively recently, art historians viewed the blocky sculptures and use of spolia in the arch as signs of poor craftsmanship, deficient artistry, and economic decline in the late Roman Empire (this reading is now almost wholly rejected by art historians). Even one of the most prolific and influential art historians of the modern age, Bernard Berenson, titled his short book on the arch, The Arch of Constantine: The Decline of Form. More recently, however, analysis of the arch has focused on the political and ideological goals of Constantine and the objectives of the artists, which has highlighted new possibilities for the interpretation of the arch.

If, indeed, the spoliated (older) material from the arch can be traced to the reigns of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius, then it situates Constantine as one worthy of the same level of reverence as those emperors—all of whom earned deserved levels of acclaim. This was vitally important to Constantine, who had himself essentially bypassed lawful succession and usurped power from others. Moreover, Constantine encouraged major social changes in Rome, such as decriminalizing Christianity. Any religious change was a threat to the ruling and political classes of Rome. By aligning himself with well-regarded emperors of Rome’s 2nd-century C.E. golden age, Constantine was signaling that he intended to model his rule after earlier, successful leaders.

Additional resources:

The Roman Empire on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Byzantium (ca. 330–1453) on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap, 2009).

Bernard Berenson, The Arch of Constantine: The Decline of Form (London: Chapman & Hall, 1954).

R. Ross Holloway “The Spolia on the Arch of Constantine” Quaderni Ticinesi Numismatica e Antichità Classiche 14 (1985), pp. 261-273.

Ernst Kitzinger, Byzantine Art in the Making: Main Lines of Stylistic Development in Mediterranean Art, 3rd-7th Century (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1977).

Jaś Elsner, “From the Culture of Spolia to the Cult of Relics: The Arch of Constantine and the Genesis of Late Antique Forms,” Papers of the British School at Rome 68 (2000), pp.149–184.

Elizabeth Marlowe, “Framing the Sun: The Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape,” The Art Bulletin vol. 88 no. 2 (June 2006), pp. 223-242.

Mark Wilson Jones, “Genesis and Mimesis: The Design of the Arch of Constantine in Rome,” The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 59 (March 2000), pp. 50–77.

The Symmachi Panel

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Holding on to pagan traditions in the early Christian era.

Video \(\PageIndex{19}\): The Symmachi Panel, c. 400 C.E., ivory, 32 x 13 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)