2.8: Ancient Rome I

- Page ID

- 63836

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Ancient Rome

Julius Caesar, the Colosseum, and the birth of Christianity—all roads lead to Rome.

753 B.C.E. - 410 C.E.

Beginner’s guide: Ancient Rome

Roman art spans almost 1,000 years and three continents from Europe into Africa and Asia.

753 B.C.E. - 410 C.E.

The mythic founding of the Roman Republic is supposed to have happened in 509 B.C.E. when the last Etruscan king was overthrown. Augustus’s rise to power in 27 B.C.E. signaled the end of the Roman Republic and the formation of the Empire. Gods and religions from other parts of the empire made their way to Rome’s capital including the Egyptian goddess Isis, the Persian god Mithras, and ultimately—Christianity.

Introduction to ancient Rome

From a republic to an empire

Legend has it that Rome was founded in 753 B.C.E. by Romulus, its first king. In 509 B.C.E. Rome became a republic ruled by the Senate (wealthy landowners and elders) and the Roman people. During the 450 years of the republic Rome conquered the rest of Italy and then expanded into France, Spain, Turkey, North Africa and Greece.

Rome became very Greek influenced or “Hellenized,” and the city was filled with Greek architecture, literature, statues, wall-paintings, mosaics, pottery and glass. But with Greek culture came Greek gold, and generals and senators fought over this new wealth. The Republic collapsed in civil war and the Roman empire began.

In 31 B.C.E. Octavian, the adopted son of Julius Caesar, defeated Cleopatra and Mark Antony at Actium. This brought the last civil war of the republic to an end. Although it was hoped by many that the republic could be restored, it soon became clear that a new political system was forming: the emperor became the focus of the empire and its people. Although, in theory, Augustus (as Octavian became known) was only the first citizen and ruled by consent of the Senate, he was in fact the empire’s supreme authority. As emperor he could pass his powers to the heir he decreed and was a king in all but name.

The empire, as it could now be called, enjoyed unparalleled prosperity as the network of cities boomed, and goods, people and ideas moved freely by land and sea. Many of the masterpieces associated with Roman art, such as the mosaics and wall paintings of Pompeii, gold and silver tableware, and glass, including the Portland Vase, were created in this period. The empire ushered in an economic and social revolution that changed the face of the Roman world: service to the empire and the emperor, not just birth and social status, became the key to advancement.

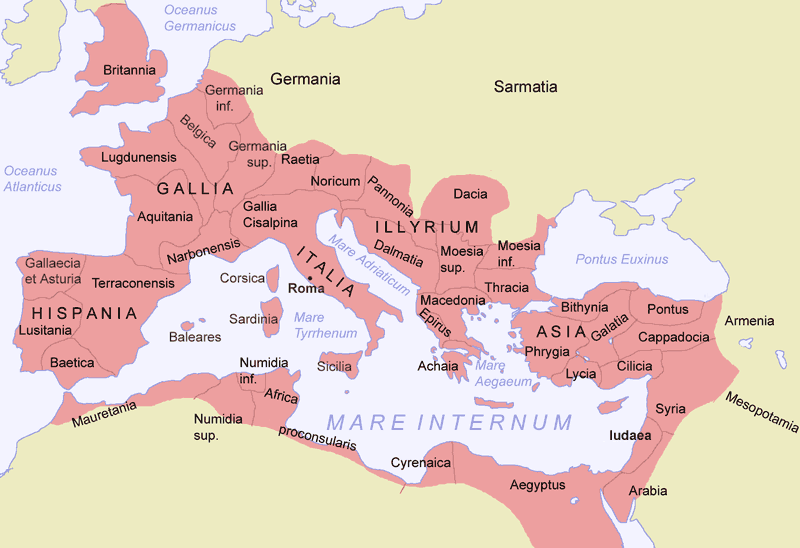

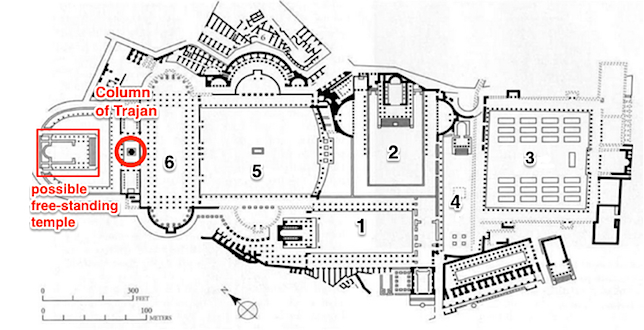

Successive emperors, such as Tiberius and Claudius, expanded Rome’s territory. By the time of the emperor Trajan, in the late first century C.E., the Roman empire, with about fifty million inhabitants, encompassed the whole of the Mediterranean, Britain, much of northern and central Europe and the Near East.

A vast empire

Starting with Augustus in 27 B.C.E., the emperors ruled for five hundred years. They expanded Rome’s territory and by about 200 C.E., their vast empire stretched from Syria to Spain and from Britain to Egypt. Networks of roads connected rich and vibrant cities, filled with beautiful public buildings. A shared Greco-Roman culture linked people, goods and ideas.

The imperial system of the Roman Empire depended heavily on the personality and standing of the emperor himself. The reigns of weak or unpopular emperors often ended in bloodshed at Rome and chaos throughout the empire as a whole. In the third century C.E. the very existence of the empire was threatened by a combination of economic crisis, weak and short-lived emperors and usurpers (and the violent civil wars between their rival supporting armies), and massive barbarian penetration into Roman territory.

Relative stability was re-established in the fourth century C.E., through the emperor Diocletian’s division of the empire. The empire was divided into eastern and western halves and then into more easily administered units. Although some later emperors such as Constantine ruled the whole empire, the division between east and west became more marked as time passed. Financial pressures, urban decline, underpaid troops and consequently overstretched frontiers – all of these finally caused the collapse of the western empire under waves of barbarian incursions in the early fifth century C.E. The last western emperor, Romulus Augustus, was deposed in 476 C.E., though the empire in the east, centered on Byzantium (Constantinople), continued until the fifteenth century.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Introduction to ancient Roman art

With the lands of Greece, Egypt, and beyond, Ancient Rome was a melting pot of cultures.

Roman art: when and where

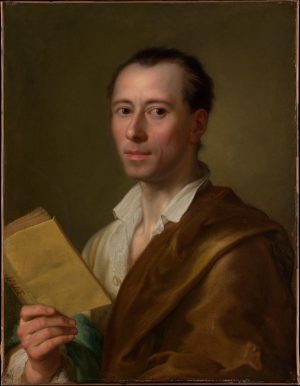

Roman art is a very broad topic, spanning almost 1,000 years and three continents, from Europe into Africa and Asia. The first Roman art can be dated back to 509 B.C.E., with the legendary founding of the Roman Republic, and lasted until 330 C.E. (or much longer, if you include Byzantine art). Roman art also encompasses a broad spectrum of media including marble, painting, mosaic, gems, silver and bronze work, and terracottas, just to name a few. The city of Rome was a melting pot, and the Romans had no qualms about adapting artistic influences from the other Mediterranean cultures that surrounded and preceded them. For this reason it is common to see Greek, Etruscan and Egyptian influences throughout Roman art. This is not to say that all of Roman art is derivative, though, and one of the challenges for specialists is to define what is “Roman” about Roman art.

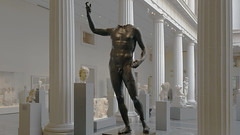

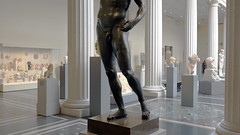

Greek art certainly had a powerful influence on Roman practice; the Roman poet Horace famously said that “Greece, the captive, took her savage victor captive,” meaning that Rome (though it conquered Greece) adapted much of Greece’s cultural and artistic heritage (as well as importing many of its most famous works). It is also true that many Romans commissioned versions of famous Greek works from earlier centuries; this is why we often have marble versions of lost Greek bronzes such as the Doryphoros by Polykleitos.

The Romans did not believe, as we do today, that to have a copy of an artwork was of any less value that to have the original. The copies, however, were more often variations rather than direct copies, and they had small changes made to them. The variations could be made with humor, taking the serious and somber element of Greek art and turning it on its head. So, for example, a famously gruesome Hellenistic sculpture of the satyr Marsyas being flayed was converted in a Roman dining room to a knife handle (currently in the National Archaeological Museum in Perugia). A knife was the very element that would have been used to flay the poor satyr, demonstrating not only the owner’s knowledge of Greek mythology and important statuary, but also a dark sense of humor. From the direct reporting of the Greeks to the utilitarian and humorous luxury item of a Roman enthusiast, Marsyas made quite the journey. But the Roman artist was not simply copying. He was also adapting in a conscious and brilliant way. It is precisely this ability to adapt, convert, combine elements and add a touch of humor that makes Roman art Roman.

Republican Rome

The mythic founding of the Roman Republic is supposed to have happened in 509 B.C.E., when the last Etruscan king, Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown. During the Republican period, the Romans were governed by annually elected magistrates, the two consuls being the most important among them, and the Senate, which was the ruling body of the state. Eventually the system broke down and civil wars ensued between 100 and 42 B.C.E. The wars were finally brought to an end when Octavian (later called Augustus) defeated Mark Antony in the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E.

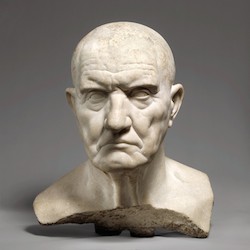

In the Republican period, art was produced in the service of the state, depicting public sacrifices or celebrating victorious military campaigns (like the Monument of Aemilius Paullus at Delphi). Portraiture extolled the communal goals of the Republic; hard work, age, wisdom, being a community leader and soldier. Patrons chose to have themselves represented with balding heads, large noses, and extra wrinkles, demonstrating that they had spent their lives working for the Republic as model citizens, flaunting their acquired wisdom with each furrow of the brow. We now call this portrait style veristic, referring to the hyper-naturalistic features that emphasize every flaw, creating portraits of individuals with personality and essence.

Imperial Rome

Augustus’s rise to power in Rome signaled the end of the Roman Republic and the formation of Imperial rule. Roman art was now put to the service of aggrandizing the ruler and his family. It was also meant to indicate shifts in leadership. The major periods in Imperial Roman art are named after individual rulers or major dynasties, they are:

Julio-Claudian (14-68 C.E.)

Flavian (69-98 C.E.)

Trajanic (98-117 C.E.)

Hadrianic (117-138 C.E.)

Antonine (138-193 C.E.)

Severan (193-235 C.E.)

Soldier Emperor (235-284 C.E.)

Tetrarchic (284-312 C.E.)

Constantinian (307-337 C.E.)

Imperial art often hearkened back to the Classical art of the past. “Classical”, or “Classicizing,” when used in reference to Roman art refers broadly to the influences of Greek art from the Classical and Hellenistic periods (480-31 B.C.E.). Classicizing elements include the smooth lines, elegant drapery, idealized nude bodies, highly naturalistic forms and balanced proportions that the Greeks had perfected over centuries of practice.

Augustus and the Julio-Claudian dynasty were particularly fond of adapting Classical elements into their art. The Augustus of Primaporta was made at the end of Augustus’s life, yet he is represented as youthful, idealized and strikingly handsome like a young athlete; all hallmarks of Classical art. The emperor Hadrian was known as a philhellene, or lover of all things Greek. The emperor himself began sporting a Greek “philosopher’s beard” in his official portraiture, unheard of before this time. Décor at his rambling Villa at Tivoli included mosaic copies of famous Greek paintings, such as Battle of the Centaurs and Wild Beasts by the legendary ancient Greek painter Zeuxis.

Later Imperial art moved away from earlier Classical influences, and Severan art signals the shift to art of Late Antiquity. The characteristics of Late Antique art include frontality, stiffness of pose and drapery, deeply drilled lines, less naturalism, squat proportions and lack of individualism. Important figures are often slightly larger or are placed above the rest of the crowd to denote importance.

In relief panels from the Arch of Septimius Severus from Lepcis Magna, Septimius Severus and his sons, Caracalla and Geta ride in a chariot, marking them out from an otherwise uniform sea of repeating figures, all wearing the same stylized and flat drapery. There is little variation or individualism in the figures and they are all stiff and carved with deep, full lines. There is an ease to reading the work; Septimius is centrally located, between his sons and slightly taller; all the other figures direct the viewer’s eyes to him.

Constantinian art continued to integrate the elements of Late Antiquity that had been introduced in the Severan period, but they are now developed even further. For example, on the oratio relief panel on the Arch of Constantine, the figures are even more squat, frontally oriented, similar to one another, and there is a clear lack of naturalism. Again, the message is meant to be understood without hesitation: Constantine is in power.

Who made Roman art?

We don’t know much about who made Roman art. Artists certainly existed in antiquity but we know very little about them, especially during the Roman period, because of a lack of documentary evidence such as contracts or letters. What evidence we do have, such as Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, pays little attention to contemporary artists and often focuses more on the Greek artists of the past. As a result, scholars do not refer to specific artists but consider them generally, as a largely anonymous group.

What did they make?

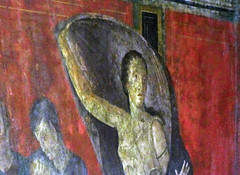

Roman art encompasses private art made for Roman homes as well as art in the public sphere. The elite Roman home provided an opportunity for the owner to display his wealth, taste and education to his visitors, dependents, and clients. Since Roman homes were regularly visited and were meant to be viewed, their decoration was of the utmost importance. Wall paintings, mosaics, and sculptural displays were all incorporated seamlessly with small luxury items such as bronze figurines and silver bowls. The subject matter ranged from busts of important ancestors to mythological and historical scenes, still lifes, and landscapes—all to create the idea of an erudite patron steeped in culture.

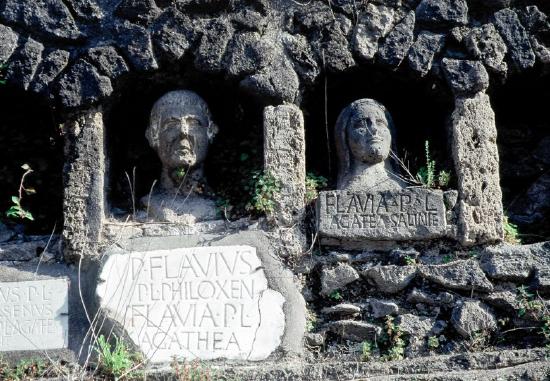

When Romans died, they left behind imagery that identified them as individuals. Funerary imagery often emphasized unique physical traits or trade, partners or favored deities. Roman funerary art spans several media and all periods and regions. It included portrait busts, wall reliefs set into working-class group tombs (like those at Ostia), and elite decorated tombs (like the Via delle Tombe at Pompeii). In addition, there were painted Faiyum portraits placed on mummies and sarcophagi. Because death touched all levels of society—men and women, emperors, elites, and freedmen—funerary art recorded the diverse experiences of the various peoples who lived in the Roman empire

The public sphere is filled with works commissioned by the emperors such as portraits of the imperial family or bath houses decorated with copies of important Classical statues. There are also commemorative works like the triumphal arches and columns that served a didactic as well as a celebratory function. The arches and columns (like the Arch of Titus or the Column of Trajan), marked victories, depicted war, and described military life. They also revealed foreign lands and enemies of the state. They could also depict an emperor’s successes in domestic and foreign policy rather than in war, such as Trajan’s Arch in Benevento. Religious art is also included in this category, such as the cult statues placed in Roman temples that stood in for the deities they represented, like Venus or Jupiter. Gods and religions from other parts of the empire also made their way to Rome’s capital including the Egyptian goddess Isis, the Persian god Mithras and ultimately Christianity. Each of these religions brought its own unique sets of imagery to inform proper worship and instruct their sect’s followers.

It can be difficult to pinpoint just what is Roman about Roman art, but it is the ability to adapt, to take in and to uniquely combine influences over centuries of practice that made Roman art distinct.

Additional resources:

Clarke, John R. Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C-A.D. 315. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003.

Kleiner, Fred S. A History of Roman Art. Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth, 2007.

Ramage, Nancy H., and Andrew Ramage. Roman Art: Romulus to Constantine. Fifth Edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc., 2008.

Stewart, Peter. The Social History of Roman Art. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Zanker, Paul. Roman Art. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010.

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Ancient Rome

by DR. BERNARD FRISCHER and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Fly over a reconstruction of one of history’s greatest cities to experience Rome as the Romans knew it. This reconstruction is based on two decades of research and the input of dozens of specialists.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\):

To learn more about the architecture seen in this video go to:

Arch of Constantine:

Arch of Titus

Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine

Roman Forum

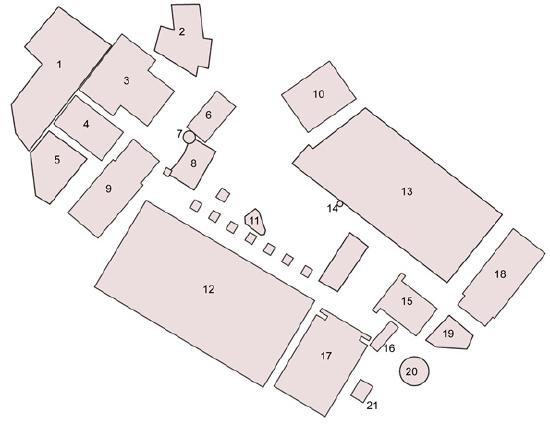

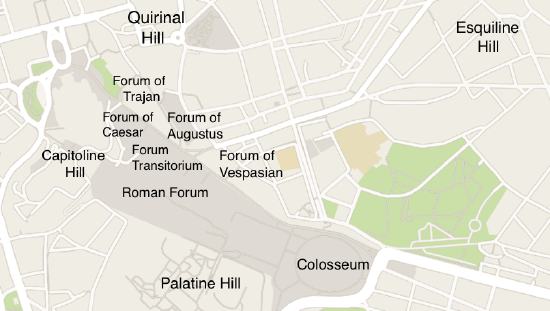

Imperial Fora

Forum and column of Trajan

Pantheon

Colosseum

To learn more about Rome Reborn, visit

https://www.romereborn.org/

Speakers: Dr. Bernie Frischer and Dr. Steven Zucker

A project between SmartHistory and Rome Reborn – with Dr. Bernard Frischer

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Rome’s history in four faces at The Met

by DR. JEFFREY A. BECKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Realism, ideal beauty, and military might—explore the evolution of Roman portraits and political imagery.

Additional resources:

Marble portrait of the emperor Caracalla at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Marble portrait bust of the emperor Gaius, known as Caligula at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Damnatio memoriae—Roman sanctions against memory

If the Roman government condemned a ruler, his portraits often died with him.

We know that Roman emperors were often raised to the status of gods after their deaths. However, just as many were given the opposite treatment—officially erased from memory.

Condemning memory

Damnatio memoriae is a term we use to describe a Roman phenomenon in which the government condemned the memory of a person who was seen as a tyrant, traitor, or other sort of enemy to the state. The images of such condemned figures would be destroyed, their names erased from inscriptions, and if the doomed person were an emperor or other government official, even his laws could be rescinded. Coins bearing the image of an emperor who had his memory damned would be recalled or cancelled. In some cases, the residence of the condemned could be razed or otherwise destroyed.\(^{[1]}\)

This was more than a form of casual, politically-motivated vandalism, carried out by disgruntled individuals, since the condemnation required approval of the Senate and the effects of the official denunciation could be seen far from Rome. There are many examples of damnatio memoriae throughout the history of the Roman Republic and Empire. As many as 26 emperors through the reign of Constantine had their memories condemned; conversely, about 25 emperors were deified after their deaths. The damning of memory phenomenon, however, is not unique to the Roman world. Egyptian pharaohs Hatshepsut and Akhenaten likewise had many of their their images, monuments, and inscriptions destroyed by political opponents or religious purists.\(^{[2]}\)

Did it work?

Instances of damnatio memoriae were not always completely successful in wiping out the memory of an individual. Among the emperors who suffered damnatio memoriae are some of the best-known figures from Roman history, including Gaius (a.k.a. Caligula) and Nero. The notoriety of these men comes to us not only from texts written during their lifetimes and later, but also from images which survived the immediate violence of the damnatio memoriae and then centuries of neglect.

For instance, one marble portrait preserves not only the image of Caligula, but also traces of paint, informing us of the existence of this condemned emperor as well as the polychromy of ancient sculpture. In antiquity, these types of images were considered very powerful and closely linked with the identity of the person they represented.

Small heads, big reputations

Caligula was the first emperor to have his images purposefully destroyed after his death. It is impossible to know how many portraits in bronze or other precious metals were melted down, but a number of marble portraits show traces of being re-cut or simply dismantled and disposed of. Workshop procedures for official imperial portraits dictated that many full-length statues in stone were to be created in two pieces. So heads of Caligula, like those now in the Getty Villa and the Yale University Art Gallery (above), could be fairly easily detached from the bodies and tossed aside and a portrait head of the new emperor would swiftly replace the offending one.

A full-length, one-piece statue of a pontifex maximus (chief state priest, a title held by the emperor) from Velleia, however, apparently underwent a kind of sculptural recycling. The face of Caligula’s successor Claudius appears rather small in comparison to the head and the rest of the body—suggesting to some scholars that it was cut down from a portrait of Caligula.

Cancelleria Reliefs: Nerva replaces Domitian

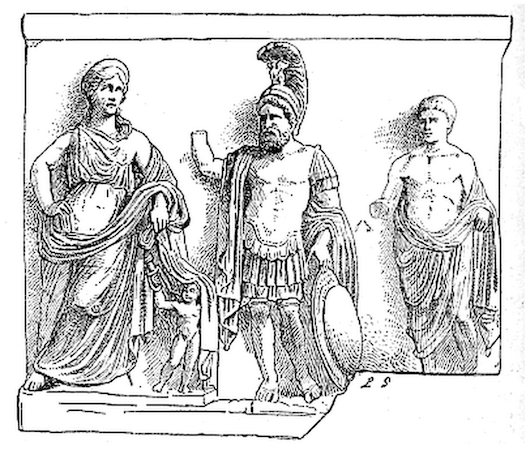

A similar re-cutting is evident on a set of reliefs found in Rome and now housed in the Vatican Museums (below). The so-called Cancelleria Reliefs show mythological and allegorical figures celebrating members of the Flavian dynasty for their military successes.

In one, Domitian departs from Rome on a military campaign, ushered out of the city by Victoria, Mars, and Minerva, as well as personifications of the Senate and the Roman people. Yet the head atop the stately tunic-clad body of the emperor is not that of Domitian. Instead it is Nerva, who succeeded Domitian after his assassination and subsequent damnatio memoriae. As in the Claudius pontifex maximus statue from Velleia, Nerva’s face is far too small for the relief and even appears comical when compared to the divinities surrounding him.\(^{[3]}\) Apparently the sculpture was recarved.

Slightly more elegant solutions for damnatio memoriae could be executed in metal statuary. The face of a bronze equestrian portrait of Domitian (below) was sawed off and replaced with that of his successor, Nerva. The result is much less jarring than on the Cancelleria relief, as the bronze “mask” was made to the same scale as the rest of the statue and the join is mostly unnoticeable.

Caracalla removes the image of Geta

Perhaps the most striking and widespread examples of damnatio memoriae come from the reign of Caracalla, a member of the Severan Dynasty who ruled from 211-217 C.E. He was initially co-emperor with his younger brother Geta, but after months of squabbling between the sibling rulers, Caracalla had Geta assassinated. This death was quickly followed by a damnatio memoriae, one in which it became a capital offense to even speak the name of the younger co-emperor.

In Rome, Geta’s image was eliminated from reliefs on the Arch of the Argentarii. No attempt at an elegant recarving was made as in the Cancelleria Reliefs; in a panel showing Septimius Severus and Julia Domna (the parents of Caracalla and Geta) sacrificing at an altar, a caduceus floats over an empty space where Geta must have stood.\(^{[4]}\) Even images of Geta’s wife and father-in-law were carved out of the Arch of the Argentarii panels, as they too had suffered a damnatio memoriae. The names of all the condemned individuals were erased from the arch and replaced with new inscriptions honoring Caracalla.

Erasing memory across time and space

A painted panel found in Egypt demonstrates the very long reach of Roman vengeance when enacting a damnatio memoriae. The panel shows the Severan family: Julia Domna wears heavy pearl earrings and necklaces; Septimius’s hair and beard are tinged with gray; and highlights in the eyes of all the figures add a lifelike quality. Caracalla’s boyish face—painted when he was merely heir to the throne—peers out to the viewer’s left. Next to him is a circular erasure in the paint where Geta once appeared. This deletion is dramatic when considering the procedures of damnatio memoriae. Someone in the province of Egypt, far from the center of the Empire, was charged with erasing the image of a child—a child who grew up to be co-emperor, only to be killed by his own brother. The tyranny of Caracalla and the thoroughness of damnatio memoriae meant that practically no image of the emperor’s enemies, no matter how small or out-of-date, would escape destruction.

Damnatio memoriae continued in the Roman world through the fourth century C.E., as seen in disfigured portraits of Constantine’s rival Maxentius. With Christianity made official in the Roman world, vandalism of imperial portraits continued, but with more of a religious bent than a political one. The fact that Roman portraits were removed, damaged, or destroyed because of dramatic changes in the subjects’ reputations is unmistakable evidence that such images are more than just “pictures.” A portrait can carry meaning over decades and centuries—whether it is of a Roman emperor, a Communist leader like Joseph Stalin, a dictator like Saddam Hussein, or Confederate generals in the United States.

Notes:

- Nero’s Domus Aurea (Golden House) in downtown Rome was eventually filled in and built over by his successors in the Flavian Dynasty, but it was not a systematic destruction. In fact, there is evidence Vespasian lived in the controversial villa before he and his sons turned the land from Nero’s private estate back over to the public.

- Hatshepsut’s successor, Thutmose III, ordered her images, cartouches, and monuments destroyed as she was seen as a usurper to his throne. Akhenaten, who brought monotheism briefly to Egypt, suffered a sort of damnatio memoriae by those who enthusiastically returned to polytheism after his death.

- In a coup de grâce for the Cancelleria Reliefs, they seem to have never been displayed, instead discarded in a Republican-period cemetery after Nerva died just fifteen months into his reign. The Flavian Dynasty was over and it would have been too challenging to re-recarve the portrait of Nerva into Trajan.

- It appears that Julia Domna’s left arm was carved in the space where Geta’s body once was; in the original format, she was probably holding the caduceus.

Additional Resources:

Sarah Bond, “Erasing the Face of History,” The New York Times, May 14, 2011

S. Bundrick and E. Varner, From Caligula to Constantine: Tyranny & Transformation in Roman Portraiture (Michael C. Carlos Museum, 2001).

Harriet I. Flower, The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace & Oblivion in Roman Political Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

Eric Varner, Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture (E.J. Brill, 2004).

Roman funeral rituals and social status: The Amiternum tomb and the tomb of the Haterii

Death, memory, and funerary rituals—monumental tombs lined the streets leading into ancient Roman cities.

To say that the ancient Romans thought a lot about funerary ritual and post-mortem commemoration is an understatement. Abundant textual evidence records complex, performative rituals surrounding death and burial in ancient Rome while significant expenditures on visual commemoration—elaborate tombs, funerary portraits—defined Roman mortuary culture.

Cemeteries and tombs lined extra-urban roads throughout the Roman world so that the mere act of exiting or entering a city brought one into immediate and direct contact with the world of the dead. In fact, Roman funerary art was not marginalized within Roman visual culture but was an integral part of it and constitutes one of the largest surviving bodies of evidence of Roman art.

Many conspicuous funerary monuments remain that commemorate the lives of elite Romans but members of other social strata also made sure to leave a lasting legacy and, indeed, funerary art is the only category of art that documents the lives of those outside of the elite. In ancient Rome, great opportunities for economic mobility existed and when people of the lower classes—former slaves (liberti) or members of a servile family—made money, they often wanted to commemorate their success by commissioning a tomb or grave marker that documented their rise to wealth. Two examples of surviving funerary monuments illustrate some of the these tendencies while providing a window into Roman funerary culture and art associated with freedmen and women, that is, people who were former slaves.

The Amiternum Tomb

The first example is a late first century B.C.E. funerary relief from Amiternum (above), located in what is now the Abruzzo region of Italy. One relief depicts a person of some consequence and shows the only existing scene in Roman art of the pompa or funerary procession that was famously described by the historian Polybius (History 6.53-4). Roman funerals were often elaborate affairs that began in the house and culminated tombside. Upon death, dramatic displays of mourning were performed by household members of the deceased’s family. Such mourning rituals included wailing, chest-beating, and sometimes self-mutilation —pulling of the hair and laceration of the cheeks. The deceased’s corpse was then washed, anointed, and displayed on a funeral bed in the house before ultimately being transported to the tomb or site of cremation on an elaborate bier in a procession known as the pompa.

For elite Romans, the pompa was a dynamic performance defined less by solemnity and more by a multi-dimensional performance designed to reflect and reinforce political and social status. These spectacles featured not only the nuclear and extended biological family but also clients, current slaves, former slaves, hired mourners paid to wail and sing dirges, and musicians playing horns, flutes, and trumpets. For elite Roman men specifically, the procession culminated in the Forum with a public eulogy attended by male family members who would wear the ancestor masks depicting deceased male relatives.

In the relief from Amiternum, the pompa scene shows a male figure, resting on an elaborate funerary couch and transported by eight pallbearers (above). Though dead, the figure appears still very much alive—tilted up on his left side and resting his head on his left hand. On either side of the central scene are all the elements of a funeral cortège. On the right pipe players, with hornblowers and a trumpeter on a floating ground line above. To the immediate right of the deceased are two women, perhaps hired mourners, one grabbing her hair and the other with her hands upraised. Most likely it is the chief mourners—the widow and children—who follow behind, to the left of the deceased.

A partial inscription found near the relief suggests that the tomb was commissioned by a person whose family was formerly of servile origins. Stylistically, the relief exhibits many of the formal characteristics typical of ‘freedmen’ art, a category of art commissioned by former slaves (or descendants of slaves) and one which largely rejected the Classicizing trappings of elite roman art. Art commissioned by freedmen and women typically exhibits disproportion, hierarchies of scale, collapsing of space or ambiguous spatial relationships, and a gestural use of line. In subject matter, freedmen art is characterized by an acute focus on self-presentation, specifically expressions of social mobility.

The pompa relief was part of an ensemble of reliefs—of which two remain—most likely inset into the fabric of a larger tomb complex that no longer survives. The other relief (above) depicts a scene of gladiatorial combat, an image type occasionally found on funerary monuments and usually understood as a reference to the public munificence of the deceased. Providing games or spectacles to the public was expected of magistrates and civil servants and such acts would be worthy of biographical commemoration. Though of servile families, freeborn men could and did rise to such offices. Considered together the two reliefs are mutually informing—displaying on the one hand, a spectacle for the public and, on the other, the spectacle of his death. As many ancient authors attest, the number of figures in a funeral procession directly correlated with the perceived importance of the deceased. While the patron of the Amiternum monument was not a member of the elite, patrician class, he certainly wanted to convey his importance by selecting two poignant images to document his biographical legacy—in recording public munificence during life and in expressing status in death.

The Tomb of the Haterii

Another tomb featuring a recognizable funerary ritual is that of the Haterii, built around 100 C.E. Discovered piecemeal in Rome since the late 1800s, the original form and layout of the tomb is unknown but the ambition of its decoration and narrative scope is obvious from the series of reliefs and portrait busts that do remain.

Constructed by a family of builders, the tomb simultaneously documents the death of the family matriarch and celebrates the family’s source of wealth. Though two busts remain of a male and female, it is the woman who appears multiple times in the visual program of the tomb’s reliefs. In the death scene, she appears on a funerary bed in the atrium of the house (above), surrounded by lit torches, a flute player at her feet, and her children beating their chests in mourning. Below the bed are three figures who wear the pileus, a cap of freedom worn by newly liberated slaves. This reference to the matron’s liberality and humanity is echoed both here with the figure reading her last will and testament beside her, as well as in another inset in which the deceased is shown making her will.

The viewer sees a conflation of time, viewing the deceased both alive and dead. In the relief above, she is shown in a retrospective portrait lounging on a couch with her children playing below. Under this vignette (below), is a grandiose temple-tomb with a portrait of deceased in the pediment and portraits of her children along the sides. In front of the tomb is a treadwheel crane which most scholars think is a reference to the family’s construction business.

The Haterii were likely involved in important building projects during the reign of the Flavian emperors (69-96 C.E.), and another relief from the tomb probably documents some of their major projects in Rome including the Flavian Amphitheater (later known as the Colosseum) and the Arch of Titus.

Whether all of the reliefs originally constituted a narrative sequence or not is debatable but what does get communicated is the considerable expenditure on this tomb and the biographical means by which it was created. Though amassing considerable wealth, the Haterii family was, nonetheless, of servile origin.

Interpretation

Both the Amiternum relief and the Haterii tomb were commissioned by patrons outside of Roman elite society, a factor that had a huge impact on the style and narrative content of the monuments. Funerary art commissioned by the Roman elite almost never referenced commerce or sources of wealth though this was a driving goal for funerary art of the freedmen. Similarly, elite monuments do not document death rituals, though elites certainly observed them. The Amiternum relief and the Haterii tomb, however, rely on a narrative interplay between death ritual and biography. For these patrons, as for many freedmen and women, their final resting places provided an ideal opportunity for documenting ritual observance and, more importantly, for documenting their success in life and commerce.

Additional Resources:

John Bodel, “Death on Display: Looking at Roman Funerals,” in The Art of Ancient Spectacle, edited by Bettina Bergmann and Christine Kondoleon, pp. 259-281 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999).

Diane Favro and Christopher Johanson, “Death in Motion: Funeral Processions in the Roman Forum,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 69.1, 2010, pp. 12-37.

Harriet I. Flower, Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in Roman Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

Valerie M. Hope, Death in Ancient Rome: A Source Book (London: Routledge, 2007).

Eleanor W. Leach, “Freedmen and Immortality in the Tomb of the Haterii,” in The Art of Citizens, Soldiers and Freedmen in the Roman World, edited by E. D’Ambra and G. Metraux, 1-18. (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2006).

J. M. C. Toynbee, Death and Burial in the Roman World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1971).

Beginner guides to Roman architecture

An introduction to ancient Roman architecture

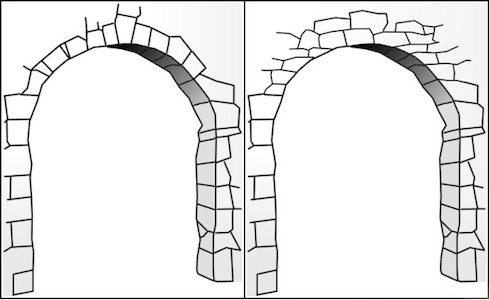

Roman architecture was unlike anything that had come before. The Persians, Egyptians, Greeks and Etruscans all had monumental architecture. The grandeur of their buildings, though, was largely external. Buildings were designed to be impressive when viewed from outside because their architects all had to rely on building in a post-and-lintel system, which means that they used two upright posts, like columns, with a horizontal block, known as a lintel, laid flat across the top. A good example is this ancient Greek Temple in Paestum, Italy.

Since lintels are heavy, the interior spaces of buildings could only be limited in size. Much of the interior space had to be devoted to supporting heavy loads.

Roman architecture differed fundamentally from this tradition because of the discovery, experimentation and exploitation of concrete, arches and vaulting (a good example of this is the Pantheon, c. 125 C.E.). Thanks to these innovations, from the first century C.E. Romans were able to create interior spaces that had previously been unheard of. Romans became increasingly concerned with shaping interior space rather than filling it with structural supports. As a result, the inside of Roman buildings were as impressive as their exteriors.

Materials, methods and innovations

Long before concrete made its appearance on the building scene in Rome, the Romans utilized a volcanic stone native to Italy called tufa to construct their buildings. Although tufa never went out of use, travertine began to be utilized in the late 2nd century B.C.E. because it was more durable. Also, its off-white color made it an acceptable substitute for marble.

Marble was slow to catch on in Rome during the Republican period since it was seen as an extravagance, but after the reign of Augustus (31 B.C.E. – 14 C.E.), marble became quite fashionable. Augustus had famously claimed in his funerary inscription, known as the Res Gestae, that he “found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble” referring to his ambitious building campaigns.

Roman concrete (opus caementicium), was developed early in the 2nd c. BCE. The use of mortar as a bonding agent in ashlar masonry wasn’t new in the ancient world; mortar was a combination of sand, lime and water in proper proportions. The major contribution the Romans made to the mortar recipe was the introduction of volcanic Italian sand (also known as “pozzolana”). The Roman builders who used pozzolana rather than ordinary sand noticed that their mortar was incredibly strong and durable. It also had the ability to set underwater. Brick and tile were commonly plastered over the concrete since it was not considered very pretty on its own, but concrete’s structural possibilities were far more important. The invention of opus caementicium initiated the Roman architectural revolution, allowing for builders to be much more creative with their designs. Since concrete takes the shape of the mold or frame it is poured into, buildings began to take on ever more fluid and creative shapes.

The Romans also exploited the opportunities afforded to architects by the innovation of the true arch (as opposed to a corbeled arch where stones are laid so that they move slightly in toward the center as they move higher). A true arch is composed of wedge-shaped blocks (typically of a durable stone), called voussoirs, with a key stone in the center holding them into place. In a true arch, weight is transferred from one voussoir down to the next, from the top of the arch to ground level, creating a sturdy building tool. True arches can span greater distances than a simple post-and-lintel. The use of concrete, combined with the employment of true arches allowed for vaults and domes to be built, creating expansive and breathtaking interior spaces.

Roman architects

We don’t know much about Roman architects. Few individual architects are known to us because the dedicatory inscriptions, which appear on finished buildings, usually commemorated the person who commissioned and paid for the structure. We do know that architects came from all walks of life, from freedmen all the way up to the Emperor Hadrian, and they were responsible for all aspects of building on a project. The architect would design the building and act as engineer; he would serve as contractor and supervisor and would attempt to keep the project within budget.

Building types

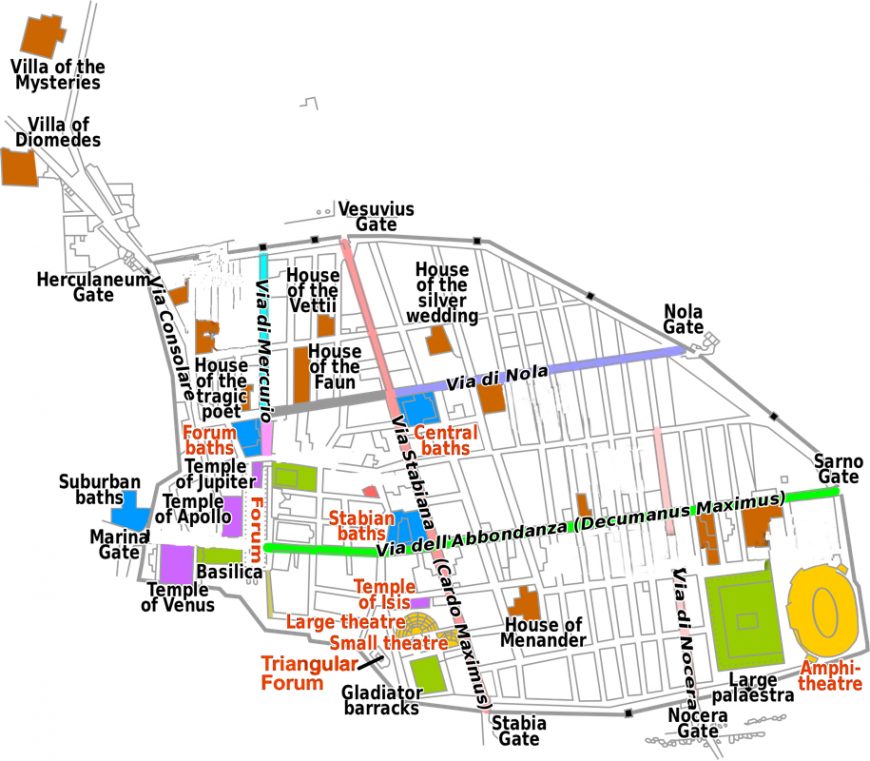

Roman cities were typically focused on the forum (a large open plaza, surrounded by important buildings), which was the civic, religious and economic heart of the city. It was in the city’s forum that major temples (such as a Capitoline temple, dedicated to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva) were located, as well as other important shrines. Also useful in the forum plan were the basilica (a law court), and other official meeting places for the town council, such as a curia building. Quite often the city’s meat, fish and vegetable markets sprang up around the bustling forum. Surrounding the forum, lining the city’s streets, framing gateways, and marking crossings stood the connective architecture of the city: the porticoes, colonnades, arches and fountains that beautified a Roman city and welcomed weary travelers to town. Pompeii, Italy is an excellent example of a city with a well preserved forum.

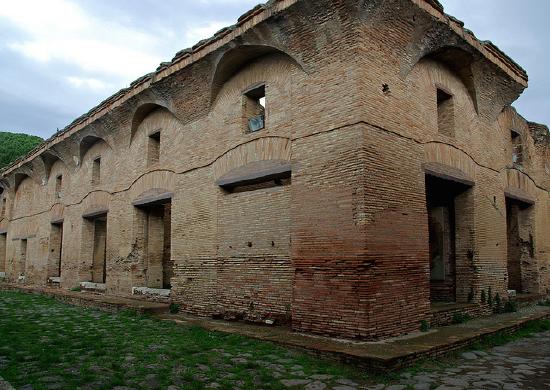

Romans had a wide range of housing. The wealthy could own a house (domus) in the city as well as a country farmhouse (villa), while the less fortunate lived in multi-story apartment buildings called insulae. The House of Diana in Ostia, Rome’s port city, from the late 2nd c. C.E. is a great example of an insula. Even in death, the Romans found the need to construct grand buildings to commemorate and house their remains, like Eurysaces the Baker, whose elaborate tomb still stands near the Porta Maggiore in Rome.

The Romans built aqueducts throughout their domain and introduced water into the cities they built and occupied, increasing sanitary conditions. A ready supply of water also allowed bath houses to become standard features of Roman cities, from Timgad, Algeria to Bath, England. A healthy Roman lifestyle also included trips to the gymnasium. Quite often, in the Imperial period, grand gymnasium-bath complexes were built and funded by the state, such as the Baths of Caracalla which included running tracks, gardens and libraries.

Entertainment varied greatly to suit all tastes in Rome, necessitating the erection of many types of structures. There were Greek style theaters for plays as well as smaller, more intimate odeon buildings, like the one in Pompeii, which were specifically designed for musical performances. The Romans also built amphitheaters—elliptical, enclosed spaces such as the Colloseum—which were used for gladiatorial combats or battles between men and animals. The Romans also built a circus in many of their cities. The circuses, such as the one in Lepcis Magna, Libya, were venues for residents to watch chariot racing.

The Romans continued to perfect their bridge building and road laying skills as well, allowing them to cross rivers and gullies and traverse great distances in order to expand their empire and better supervise it. From the bridge in Alcántara, Spain to the paved roads in Petra, Jordan, the Romans moved messages, money and troops efficiently.

Republican period

Republican Roman architecture was influenced by the Etruscans who were the early kings of Rome; the Etruscans were in turn influenced by Greek architecture. The Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill in Rome, begun in the late 6th century B.C.E., bears all the hallmarks of Etruscan architecture. The temple was erected from local tufa on a high podium and what is most characteristic is its frontality. The porch is very deep and the visitor is meant to approach from only one access point, rather than walk all the way around, as was common in Greek temples. Also, the presence of three cellas, or cult rooms, was also unique. The Temple of Jupiter would remain influential in temple design for much of the Republican period.

Drawing on such deep and rich traditions didn’t mean that Roman architects were unwilling to try new things. In the late Republican period, architects began to experiment with concrete, testing its capability to see how the material might allow them to build on a grand scale.

The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia in modern day Palestrina is comprised of two complexes, an upper and a lower one. The upper complex is built into a hillside and terraced, much like a Hellenistic sanctuary, with ramps and stairs leading from the terraces to the small theater and tholos temple at the pinnacle. The entire compound is intricately woven together to manipulate the visitor’s experience of sight, daylight and the approach to the sanctuary itself. No longer dependent on post-and-lintel architecture, the builders utilized concrete to make a vast system of covered ramps, large terraces, shops and barrel vaults.

Imperial period

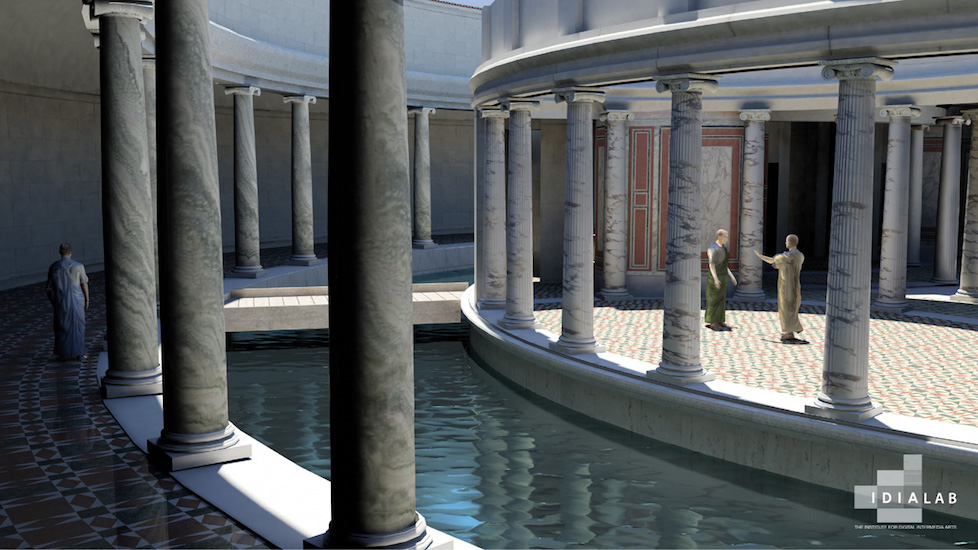

The Emperor Nero began building his infamous Domus Aurea, or Golden House, after a great fire swept through Rome in 64 C.E. and destroyed much of the downtown area. The destruction allowed Nero to take over valuable real estate for his own building project; a vast new villa. Although the choice was not in the public interest, Nero’s desire to live in grand fashion did spur on the architectural revolution in Rome. The architects, Severus and Celer, are known (thanks to the Roman historian Tacitus), and they built a grand palace, complete with courtyards, dining rooms, colonnades and fountains. They also used concrete extensively, including barrel vaults and domes throughout the complex. What makes the Golden House unique in Roman architecture is that Severus and Celer were using concrete in new and exciting ways; rather than utilizing the material for just its structural purposes, the architects began to experiment with concrete in aesthetic modes, for instance, to make expansive domed spaces.

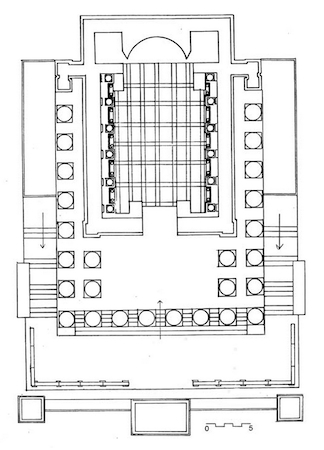

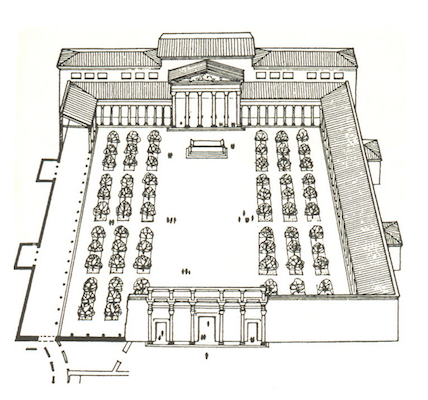

Nero may have started a new trend for bigger and better concrete architecture, but Roman architects, and the emperors who supported them, took that trend and pushed it to its greatest potential. Vespasian’s Colosseum, the Markets of Trajan, the Baths of Caracalla and the Basilica of Maxentius are just a few of the most impressive structures to come out of the architectural revolution in Rome. Roman architecture was not entirely comprised of concrete, however. Some buildings, which were made from marble, hearkened back to the sober, Classical beauty of Greek architecture, like the Forum of Trajan. Concrete structures and marble buildings stood side by side in Rome, demonstrating that the Romans appreciated the architectural history of the Mediterranean just as much as they did their own innovation. Ultimately, Roman architecture is overwhelmingly a success story of experimentation and the desire to achieve something new.

Additional resources:

James C. Anderson Jr., Roman Architecture and Society (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

Diana Kleiner, Roman Architecture: A Visual Guide (Kindle) (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).

William J. MacDonald, The Architecture of the Roman Empire, vol. I: An Introductory Study (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982).

Frank Sear, Roman Architecture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983).

J.B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Italo-Roman building techniques

Building techniques represent an important means through which to study and understand ancient structures. The building technique chosen for a given project can indirectly provide a good deal of information about the building itself, in terms of helping archaeologists and art historians to understand scale, scope, expense, and technique, alongside other, more aesthetic considerations. The building technique can also inform the chronology of the structure and can indicate, in some cases, other economic factors based on the building materials employed. The masonry techniques discussed here cover a broad chronological range from the second millennium B.C.E. to Late Antiquity.

Megalithic techniques

From the second millennium B.C.E. onwards techniques of megalithic architecture were used in Italy and on the island of Sardinia. As the name suggests, such techniques involved the use of large unworked (or roughly worked) stones to create walls and structures. Such walls tend to be built in a dry stone technique, meaning that no bonding agents are used to join stones, rather the tight fit and gravity itself are relied upon to hold the stones in place. Such techniques are frequently referred to under the general heading of “Cyclopean masonry”, indicative of the great bulk of the stones used.

On Sardinia, distinctive tower structures known as nuraghe built during the second and first millennia B.C.E. utilized megalithic techniques, including the construction of corbel vaults. In peninsular Italy, the distinctive style of polygonal masonry emerged by the second half of the first millennium B.C.E. Often used to construct defensive walls, retaining walls, and terraces, this type of megalithic architecture assumed a distinctive polygonal pattern.

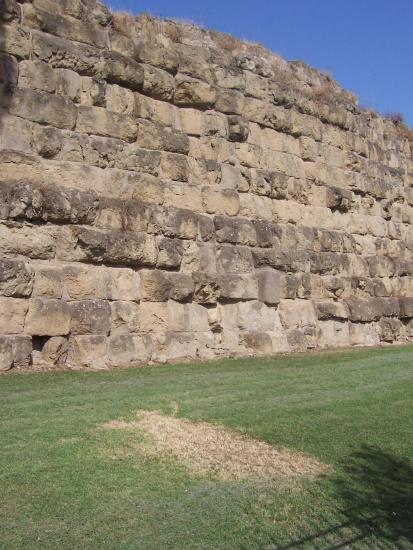

Ashlar masonry (opus quadratum)

Ashlar or cuboidal masonry (cut, squared stones), referred to as opus quadratum by the Romans, represents an important advance in building technology. In Italy, the widespread use of ashlar masonry occurs from the sixth century B.C.E. onward. At Rome, this adoption corresponded to a marked increase in monumental construction projects during the late archaic period. Initially, Romans made use of a locally available tufo type known as cappellaccio. While a prestige material, its overall low quality led to the Romans being eager for other sources of superior tufo — a new source of tufo became available once Rome sacked the Etruscan city of Veii in 396 B.C.E.

Ashlar masonry, in general, is used primarily where underlying bedrock is softer and more easily shaped, such as the tufo plateaus on which the city of Rome and many of her Etruscan neighbors sit. Ashlar masonry is phased in for use in monumental construction projects. Notable examples in the city of Rome include the so-called “Servian walls” surrounding the city of Rome and the late sixth century B.C.E. podium of the Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus. Although ashlar techniques would never completely disappear, the emergence of Roman concrete (opus caementicium) during the second century B.C.E. came to offer greater flexibility and strength than ashlar masonry could.

Opus caementicium (“cement work”)

“Roman concrete” describes a category of building technology that involves the use of concrete. Concrete is defined as a heavy, durable building material made from a mixture of sand, lime, water, and inclusions (caementa) such as stone, gravel or terracotta. It can either be spread or poured into molds or frames; it forms a stone-like mass upon hardening. In chronological terms, the ancient Roman usage of concrete stretches from sometime in the second century B.C.E. to Late Antiquity (and beyond). Within that chronological span, the technology of concrete changed and developed over time so that we may observe differences that relate to both function and aesthetics.

The basic concept of Roman concrete walling is to create a concrete core that is then faced with stone or brick and perhaps faced even further with stucco, paint, or polished stone veneers. Roman concrete is strong, practical, and functional — it is, on its own, rarely deemed aesthetically beautiful but its versatility and load-bearing potential facilitated the construction of many of the most famous buildings of Roman antiquity. The trio of the Domus Aurea of Nero, the Flavian Amphitheater, and the Pantheon could never have been realized without the innovative use of concrete building technology.

Roman concrete is famously strong and durable — even in archaeological contexts concrete is remarkable for its longevity. While the Romans did not invent concrete per se, they improved their own version of concrete by means of additions to its formula. Volcanic sand known as pozzolana (or “pit sand”) was favored by Roman builders for mixing concrete. When pozzolana, which contains high quantities of both aluminum oxide (sometimes called alumina) and silica, was added to mortar, the water-resistant properties of the mortar increased. This hydraulic concrete was then ideal for use in building piers, breakwaters, and bridge pylons, among other structures.

Typology

The Roman architectural writer Vitruvius (first century B.C.E.) provides a thorough summary of building techniques in his 10-book treatise De architectura (“On architecture”). In most cases, modern scholars continue to employ the Latin terminology used by Vitruvius. In these typological categories, the Latin term opus means “work or technique”.

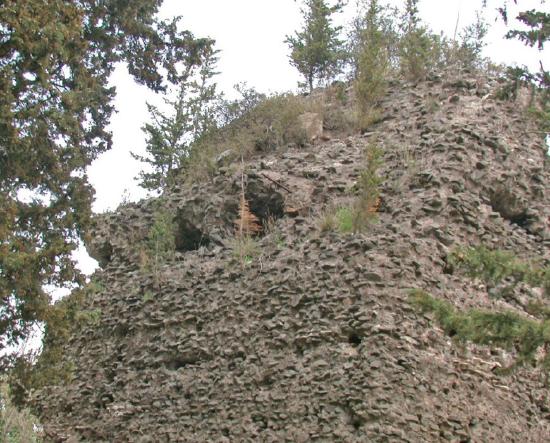

Opus incertum (“irregular work”) is an early concrete technique that emerged during the earlier second century B.C.E. and continued in use until the middle of the first century B.C.E., gradually abandoned in favor of opus reticulatum. Opus incertum may be identified on the basis of its use of randomly placed, fist-sized chunks of tufo or stone that are placed into a core of opus caementicium.

Opus reticulatum (“reticulate work”) is a technique that employs diamond-shaped pieces of tufo known as cubilia that are placed within a core of concrete. The resulting pattern of the flat ends of these blocks form the net-shaped pattern that lends its name to the technique. Opus reticulatum became popular during the early first century B.C.E. It would eventually be superseded by opus latericium.

Opus latericium (“brickwork”) describes a masonry technique that employs courses of laid bricks that are used to face a wall core of opus caementicium. This is a predominant technique during the Roman Imperial period. The bricks, in turn, would often be coated with stucco or another form of wall revetment.

Opus mixtum (“mixed work”) is a technique that combines opus reticulatum with opus latericium. The latter is usually found at the margins of the wall. It is a technique most common during the Hadrianic period in the mid-second century C.E.

Opus vittatum or opus listatum is a later Roman concrete technique that is adopted in the early fourth century C.E. This technique alternated horizontal courses of tufo with alternating courses of bricks. This technique is particularly evident in building projects of Constantine I.

Additional resources:

Jean Pierre Adam, Roman building: materials and techniques (trans. Anthony Matthews) (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994).

Larry F. Ball, The Domus Aurea and the Roman architectural revolution (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Marion E. Blake, Ancient Roman Construction in Italy from the Prehistoric Period to Augustus. (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1947).

Marion E. Blake, Construction in Italy from Tiberius through the Flavians. (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1959).

C. J. Brandon et al., Building for eternity: the history and technology of Roman concrete engineering in the sea (Oxford: Oxbow, 2014).

Pierre Gros, L’architecture romaine: du début du IIIe siècle av. J.-C. à la fin du Haut-Empire. 1, Les monuments publics (Paris: Picard, 1996).

Cairoli Fulvio Giuliani, L’edilizia nell’antichità (Rome: NIS, 1990).

Lynne Lancaster, Concrete vaulted construction in imperial Rome: innovations in context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Lynne Lancaster, Innovative vaulting in the architecture of the Roman Empire: 1st to 4th centuries CE (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Giuseppe Lugli, La tecnica edilizia romana con particolare riguardo a Roma e Lazio 2 v. (Rome: G. Bardi, 1957).

David Macaulay, City: A Story of Roman Planning and Construction (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1974).

William L. MacDonald, The Architecture of the Roman Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965).

William L. MacDonald, The Pantheon: Design, Meaning and Progeny (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976).

Carmelo G. Malacrino, Constructing the Ancient world: architectural techniques of the Greeks and Romans (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010).

Esther Boise van Deman, “Methods of Determining the Date of Roman Concrete Monuments,” American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1912), pp. 230-251.

John Bryan Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

Roman Domestic architecture: the Domus

The domus was more than a residence, it was also a statement of social and political power.

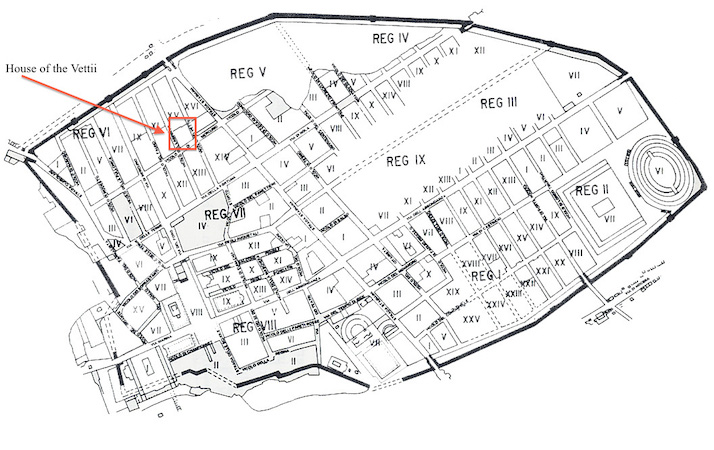

Introduction

Understanding the architecture of the Roman house requires more than simply appreciating the names of the various parts of the structure, as the house itself was an important part of the dynamics of daily life and the socio-economy of the Roman world. The house type referred to as the domus (Latin for “house”) is taken to mean a structure designed for either a nuclear or extended family and located in a city or town. The domus as a general architectural type is long-lived in the Roman world, although some development of the architectural form does occur. While the sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum provide the best surviving evidence for domus architecture, this typology was widespread in the Roman world.

Layout

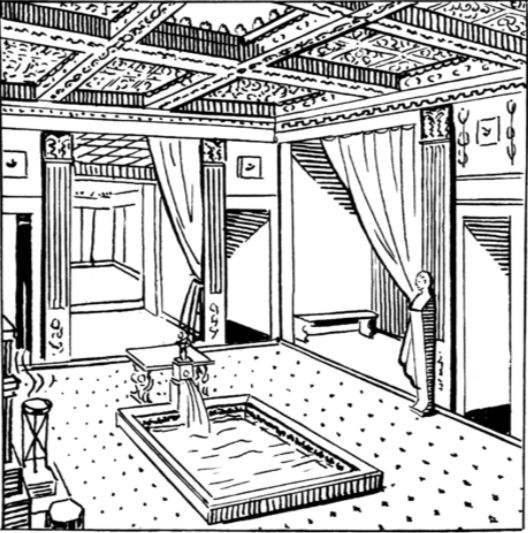

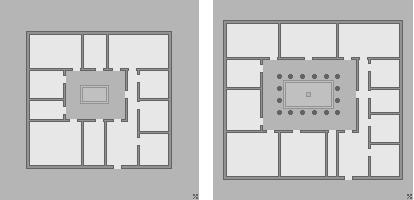

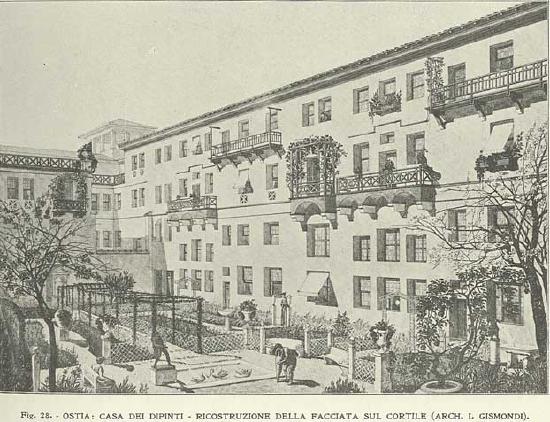

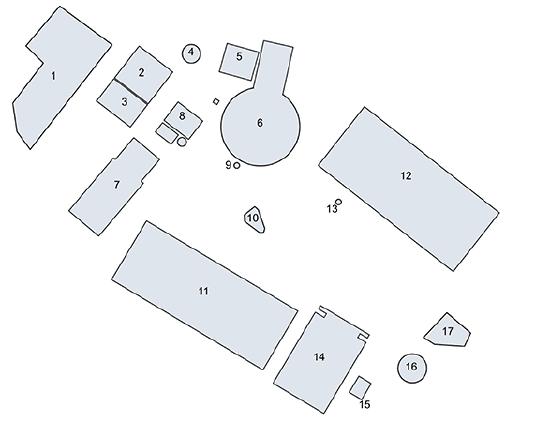

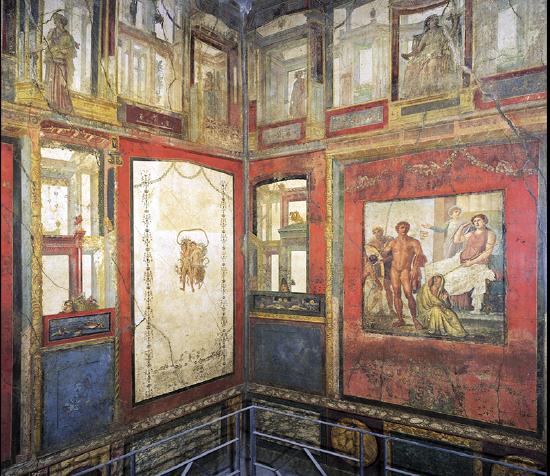

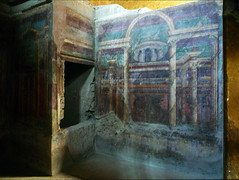

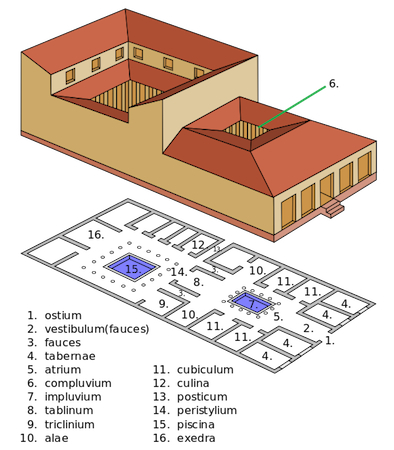

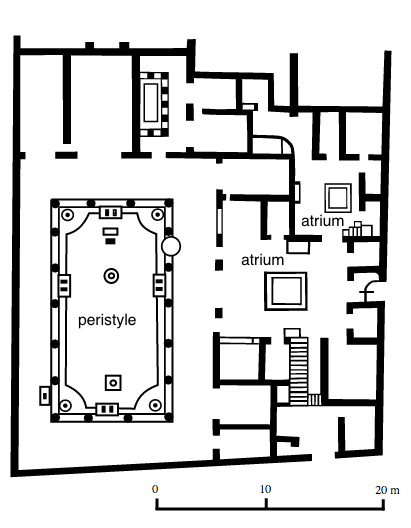

While there is not a “standard” domus, it is possible to discuss the primary features of a generic example, keeping in mind that variation is present in every manifest example of this type of building. The ancient architectural writer Vitruvius provides a wealth of information on the potential configurations of domus architecture, in particular the main room of the domus that was known as the atrium (no. 3 in the diagram above).

In the classic layout of the Roman domus, the atrium served as the focus of the entire house plan. As the main room in the public part of the house (pars urbana), the atrium was the center of the house’s social and political life. The male head-of-household (paterfamilias) would receive his clients on business days in the atrium, in which case it functioned as a sort of waiting room for business appointments. Those clients would enter the atrium from the fauces (no. 1 in the diagram above), a narrow entry passageway that communicated with the street. That doorway would be watched, in wealthier houses, by a doorman (ianitor). Given that the atrium was a room where invited guests and clients would wait and spend time, it was also the room on which the house owner would lavish attention and funds in order to make sure the room was well appointed with decorations. The corner of the room might sport the household shrine (lararium) and the funeral masks of the family’s dead ancestors might be kept in small cabinets in the atrium. Communicating with the atrium might be bed chambers (cubicula—no. 8 in the diagram above), side rooms or wings (alae—no. 7 in the diagram above), and the office of the paterfamilias, known as the tablinum (no. 5 in the diagram above). The tablinum, often at the rear of the atrium, is usually a square chamber that would have been furnished with the paraphernalia of the paterfamilias and his business interests. This could include a writing table as well as examples of strong boxes as are evident in some contexts in Pompeii.

Types of atria

The arrangement of the atrium could take a number of possible configurations, as detailed by Vitruvius (De architectura 6.3). Among these typologies were the Tuscan atrium (atrium Tuscanicum), the tetrastyle atrium (atrium tetrastylum), and the Corinthian atrium (atrium Corinthium). The Tuscan form had no columns, which required that rafters carry the weight of the ceiling. Both the Tetrastyle and the Corinthian types had columns at the center; Corinthian atria generally had more columns that were also taller.

All three of these typologies sported a central aperture in the roof (compluvium) and a corresponding pool (impluvium—no. 4 in the diagram above) set in the floor. The compluvium allowed light, fresh air, and rain to enter the atrium; the impluvium was necessary to capture any rainwater and channel it to an underground cistern. The water could then be used for household purposes.

Beyond the atrium and tablinum lay the more private part (pars rustica) of the house that was often centered around an open-air courtyard known as the peristyle (no. 11 in the diagram above). The pars rustica would generally be off limits to business clients and served as the focus of the family life of the house. The central portion of the peristyle would be open to the sky and could be the site of a decorative garden, fountains, artwork, or a functional kitchen garden (or a combination of these elements). The size and arrangement of the peristyle varies quite a bit depending on the size of the house itself.

Communicating with the peristyle would be functional rooms like the kitchen (culina—no. 9 in the diagram above), bedrooms (cubicula—no. 8 in the diagram above), slave quarters, latrines and baths in some cases, and the all important dining room (triclinium—no. 6 in the diagram above). The triclinium would be the room used for elaborate dinner parties to which guests would be invited. The dinner party involved much more than drinking and eating, however, as entertainment, discussion, and philosophical dialogues were frequently on the menu for the evening. Those invited to the dinner party would be the close friends, family, and associates of the paterfamilias. The triclinium would often be elaborately decorated with wall paintings and portable artworks. The guests at the dinner party were arranged according to a specific formula that gave privileged places to those of higher rank.

Chronology and development

No architectural form is ever static, and the domus is no exception to this rule. Architectural forms develop and change over time, adapting and reacting to changing needs, customs, and functions. The chronology of domus architecture is contentious, especially the discussion about the origins and early influences of the form.

Many ancient Mediterranean houses show the same propensity as the Roman atrium house—a penchant for a plan that focuses on a central courtyard. The Romans may have drawn architectural inspiration from the Etruscans, as well as from the Greeks. In truth it is unlikely that there was a single stream of influence, rather Roman architecture responds to streams of influence that pervade the Mediterranean.

By the second and first centuries B.C.E., the domus had become fairly well established and it is to this period that most of the houses known from Pompeii and Herculaneum date. During the Republic the social networking system that we refer to as the “patron-client relationship” was not only active, but essential to Roman politics and business. This organizational scheme changed as Rome’s political system developed.

With the advent of imperial rule by the late first century B.C.E., the emperor became the universal patron, and clientage of the Republican variety relied less heavily on its old traditions. House plans may have changed in response to these social changes. One clear element is a de-emphasis of the atrium as the key room of the house. Examples such as the multi-phase House of Cupid and Psyche at Ostia (2nd-4th centuries C.E.) demonstrate that the atrium eventually gives way to larger and more prominent dining rooms and to courtyards equipped with elaborate fountains.

Additional resources:

Roman Housing on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Jean-Pierre Adam, Roman Building: Materials and Techniques, trans. Anthony Mathews (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 1994).

Penelope M. Allison, “The Relationship between Wall-decoration and Room-type in Pompeian Houses: A Case Study of the Casa della Caccia Antica,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 5 (1992), pp. 235-49.

Penelope M. Allison, Pompeian Households. An Analysis of the Material Culture (Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles, 2004). (online companion)

Bettina Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii,” The Art Bulletin 76.2 (1994) 225-256.

C. F. M. Bruun, “Missing Houses: Some Neglected domus and Other Abodes in Rome,” Arctos 32 (1998), pp. 87-108.

John R. Clarke, The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.-A.D. 250: ritual, space, and decoration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991).

A. E. Cooley and M.G.L. Cooley, Pompeii and Herculaneum: a sourcebook, second ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2014).

Peter Connolly, Pompeii (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990).

Kate Cooper, “Closely Watched Households: Visibility, Exposure and Private Power in the Roman Domus,” Past & Present 197 (2007), pp. 3-33.

Eugene Dwyer, “The Pompeian Atrium House in Theory and Practice,” in E.K. Gazda, ed., Roman Art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Decor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991), pp. 25-48.

Carol Mattusch, Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture around the Bay of Naples (Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2008.)

August Mau, Pompeii: its life and art (Washington D.C.: McGrath, 1973).

D. Mazzoleni, U. Pappalardo, and L. Romano, Domus: Wall Painting in the Roman House (Los Angeles: J Paul Getty Museum, 2005).

Alexander G. McKay, Houses, Villas, and Palaces in the Roman World (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press,1975).

G.P.R. Métraux, “Ancient Housing: Oikos and Domus in Greece and Rome,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 58 (1999), pp. 392-405.

Salvatore Nappo, Pompeii: a guide to the ancient city (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1998).

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, “The development of the Campanian house,” in J.J. Dobbins and P.W. Foss, eds., The World of Pompeii (London and New York: Routledge, 2007) 279-91.

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, “Rethinking the Roman Atrium House,” in R. Laurence and A. Wallace-Hadrill, eds., Domestic Space in the Roman World: Pompeii and Beyond (Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1997).

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, “The Social Structure of the Roman House,” Papers of the British School at Rome 56 (1988), pp. 43–97.

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996).

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Herculaneum: Past and Future (London : Frances Lincoln Limited, 2011).

Timothy Peter Wiseman, “Conspicui postes tectaque digna deo: The Public Image of Aristocratic Houses in the Late Republic and Early Empire,” in L’Urbs: Espace urbain et histoire (1er siècle av. J.C.-IIIe siècle ap. J.C.) (Rome: Ecole Française de Rome, 1987) 393-413.

Paul Zanker, Pompeii: Public and Private Life, trans. D. L. Schneider (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998).

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Roman domestic architecture: the villa

To escape the heat and pressures of the city, the wealthiest Roman families retreated to their country homes.

Familiar but enigmatic

The villa, on its face, seems to be the simplest of Roman domestic buildings to understand—after all, we continue to use the Latin term “villa” to conjure up a luxurious retreat in the country or at the seashore.

We find evidence of the ancient Roman villa in both archaeological remains and in ancient texts. Taken together this would seem to suggest a fairly uniform and monolithic body of architecture, while the reality is, in fact, something quite different. In some ways the Roman villa is a conundrum. This is especially true in the earlier phases of the type’s development, where questions of origins and influence remain hotly debated. As a building type, the villa manages to simultaneously seem instantly understandable and completely enigmatic.

History

The earliest examples of buildings grouped into this category, sometimes referred to by the term villa rustica (country villa), are mostly humble farmhouses in Italy. These rural structures tend to be associated with agriculture or viticulture (grapes) on a small scale. The villa form—and the term itself—then comes to be appropriated and applied to a whole range of structures that persist across both the Republican and Imperial periods, continuing into Late Antiquity. One thing that all villas tend to have in common is their extra-urban setting—the villa is not an urban structure, but rather a rural one. Thus we most often find them in rural, suburban or coastal settings most often. In ideological terms, the country (rus) provided relief from the hectic pressures of the city (urbs), and thus the villa became associated (and remains associated) with rural getaways.

According to Pliny the Elder, the villa urbana was located within easy distance of the city, while the villa rustica was a permanent country estate staffed with slaves and a supervisor (vilicus). The villa rustica is connected with agricultural production and the villa complex can contain facilities and equipment for processing agricultural produce, notably processing grapes to make wine and processing olives to produce olive oil. Even opulent villas often had a pars rustica, the working or productive part of the building. Latin authors like Cato the Elder and Varro even made and observed strict recommendations, based in agrarian ideology, as to how these rustic villas should be built, appointed, and managed.

Building typology

It is difficult to identify a single, uniform typology for Roman villas, just as it is difficult to do so for the Roman house (domus). In general terms the ideal villa is internally divided into two zones: the urbane zone for enjoying life (pars urbana) and the productive area (pars rustica). As with domus architecture, villas often focus internally around courtyards and atrium spaces. Elite villas tend to be sprawling affairs, with many rooms for entertainment and dining, in addition to specialized facilities including heated baths (balnea).

Republican villas

Villas built in Italy during the period stretching from the fifth to the second centuries B.C.E. can be divided into several groupings, based on their building typology. One typology with the smallest number of known examples is an opulent villa that draws its influence from the tradition of palatial aristocratic compounds of the Archaic period in central Italy, such as the complex at Poggio Civitate (Murlo) and the “palace” at Acquarossa (near Viterbo). These aristocratic compounds might have inspired Roman Republican aristocrats to build similar aristocratic mansions for their extended families as a demonstration of their social and economic clout. Other Republican period “villas” tend to be small and connected with agricultural production on a small scale. Traditionally they are associated with an open-air, yet enclosed, courtyard that serves as a focal point.

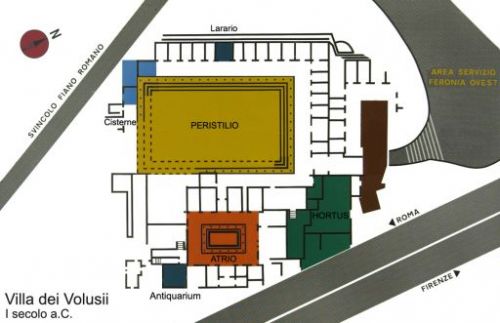

The mid-first century B.C.E. villa of the Volusii Saturnini at Lucus Feroniae (left) provides a good example of an opulent villa built by Late Republican new money. It also demonstrates the pattern that many elite villas would follow during the Imperial period in becoming ever more opulent. In the plan, we see a large peristyle (a garden surrounded by columns) and smaller atrium (an open courtyard) and dozens of rooms off each.

Ancient writers the likes of Cato the Elder (a Roman senator who was born in the late 3rd century B.C.E.), Varro (a scholar and writer from the first century C.E.), and Columella (who wrote about agriculture in the first century C.E.) theorized that villa architecture evolved over time, with the so-called “Columellan” villa being the most elaborate and sophisticated. While scholars do not accept this evolutionary schema any longer, it is interesting that these ancient authors were focused on villas and their culture and that they appreciated change over time. While the archaeological remains do not bear out or prove this theory of architectural development, the awareness of the villa and its role in Roman ideology is an important concept on its own.

Imperial villas

From the Imperial period, we are fortunate to have evidence for a wide range of villa architecture distributed across the Roman empire. In the provinces of the Roman Empire, the adoption of classic villa architecture seems to serve as a mark of adopting a Roman lifestyle—with elites keen to demonstrate their urbanity by living in villas. An example of such an adoption is the so-called Fishbourne Roman palace at Chichester in the south of England which was likely the seat of the Roman client-king Cogidubnus.

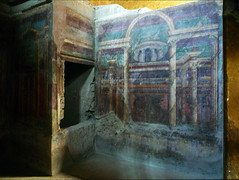

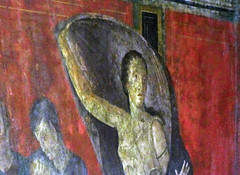

A number of villas destroyed by the 79 C.E. eruption of Mount Vesuvius demonstrate key features of the opulent villa. At Boscoreale the Late Republican villa of Publius Fannius Synistor (c. 50-40 B.C.E.) is well known for its elaborate Second Style wall paintings (below).

At Oplontis (modern Torre Annunziata, Italy), the so-called Villa A (sometimes referred to as Villa Poppaea) demonstrates the seaside villa (villa maritima). This is a grand pleasure villa, with many well-appointed rooms for leisure and reception.

In the periphery of Rome itself we find a number of villas connected with the Imperial house. These are mostly villas of the villa urbana category—including examples such as the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta that belonged to Livia, the wife of the emperor Augustus. The Prima Porta villa—a private Imperial retreat—is famous for its garden-themed dining room and the portrait statue of Augustus of Prima Porta.