11.5: Late Empire

- Page ID

- 108668

Late Empire & Decline of the Roman Empire

By Lumen Learning

The Severan Dynasty was the last stable period of imperial reign over the Roman Empire until that of Constantine. The assassination of Commodus in 192 CE once again plunged the Roman Empire into a year of civil war. Five generals succeeded one another until the fifth, Septimius Severus, consolidated power and managed to reign over Rome until his death from illness, 19 years later in 211 CE. He established the Severan Dynasty that reigned until 235 CE, overseen by five different emperors. Unfortunately for Rome, the economy and the bureaucratic and administrative power of the Emperor and the Senate were declining during this time. The five Severan emperors faced great difficulties maintaining control over the empire. Their troubles demonstrate the importance of this pivotal period that ultimately led to Rome’s decline.

Septimius Severus

To strengthen his claim as emperor, Septimius Severus declared himself to be the secret son of Marcus Aurelius and even had his portrait fashioned in a similar manner to him. Like Marcus Aurelius, Septimius Severus wore his beard thick and curly in the style of Greek philosophers. His portraits show him as old, but fit and without the winkles of wisdom seen in Republican veristic portraiture.

Triumphal Arches of Septimius Severus

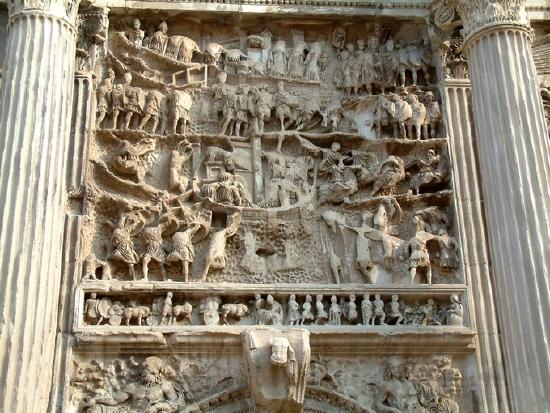

Two triumphal arches commissioned by Septimius Severus still stand today: the first at the northwest entrance to the Roman forum, and the second on the main road leading into the city of Leptis Magna, the Roman colony in modern Libya where Septimius Severus was born. Both were erected in 203 CE and commemorate the emperor’s victory over the Parthians.

The Roman Arch of Septimius Severus recalls the triumphal arch of Augustus, also erected to honor his own victory over the Parthians. Like Augustus’ arch, that of Septimius is a triple arch—the only surviving one in Rome (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Decorative panels depict scenes of conquest echoing the military scenes on the Columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius. These, however, depart from the Classical style, stylistically resembling more the figures on the Column of Marcus Aurelius. The figures on the panels are carved in high relief, and each shows multiple scenes.

Small friezes recounting the triumphal procession also frame the panels. Other decorative elements include winged victories in the spandrels and two sets of four columns, one on each side, that frame the archways.

The columns are free-standing, decorative additions to the arch. On the pedestal of each are reliefs of Romans leading captive Parthians away. This arch visually recalls the triumphal arches of the past that stood in the Roman Forum and expresses the continuity of Septimius Severus’ imperial rule and the momentum of the empire (see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Baths of Caracalla

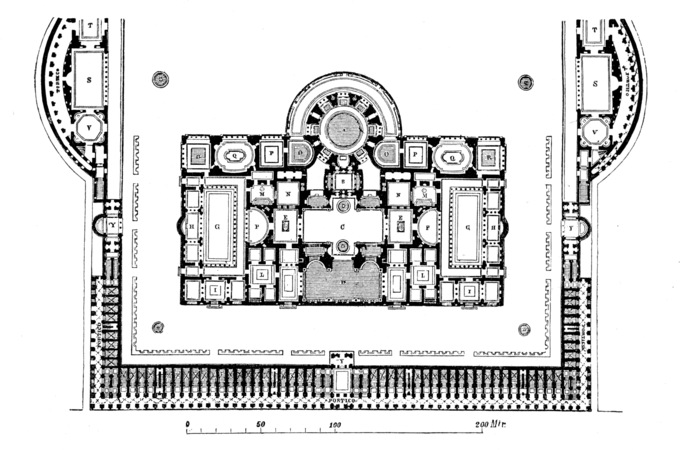

Caracalla was one of the last emperors of the century who had the time, resources, and power to build in the city of Rome. His longest-lasting contribution is a large bath complex that stands to the southeast of Rome’s center. It covered over 33 acres and could hold over 1,600 bathers at a time. Bathing was an important part of Roman daily life, and the baths were a place for leisure, business, socializing, exercising, learning, and illicit affairs. These baths not only held the traditional bathing pools but also exercise courts, changing rooms, and Greek and Latin libraries. A mithraeum has also been found on the site.

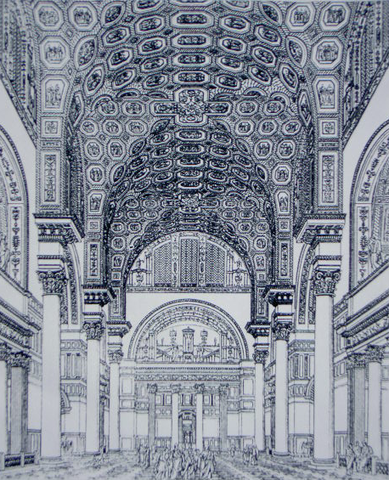

Architecturally, the Baths of Caracalla demonstrate the impressive mastery of Roman building and the importance of concrete and the vaulting systems developed by the Romans to create large and impressive buildings with ceilings that span great distances. The building was lavishly decorated with marble veneer, fanciful mosaics, and monumental Greek marble statues (see the vast floorplan for the Baths of Caracalla in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) and the reconstruction drawing in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Quirinal Hill Serapeum

In 212, Caracalla erected a temple, called a Serapeum, on Quirinal Hill dedicated to the Egyptian god Serapis, a human-headed deity who shared Greek and Egyptian attributes. This Serapeum was, by most surviving accounts, the most sumptuous and architectonically ambitious of those built on the hill (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

The temple covered over three acres. It was composed by a long courtyard, surrounded by a colonnade, and by the ritual area, where statues and obelisks were erected. Designed to impress its visitors, the temple boasted columns nearly 70 feet tall and over six feet in diameter, sitting atop a marble stairway that connected the base of the hill to the sanctuary.

The ruins of the Serapeum show a mixture of brick and concrete with a regular use of the round arch. Symbolically, the temple signified the diversity that the Roman pantheon had reached by the third century.

Sculpture during the Decline of the Roman Empire

The Dominate Period, when warring generals controlled Rome, was a time marked by insecurity, anxiety, and a rapid succession of emperors.

After Caracalla

Emperor Caracalla was assassinated while campaigning against the Parthians in 217 CE. He was quickly succeeded by a member of his personal guard, Macrinus, who ruled for less than a year before his own death. Elagabalus, the grandson of Julia Domna’s sister, and his cousin Alexander Severus were the last in the Severan line. Both men managed to maintain control of Rome, and Alexander Severus was even able to improve the economic condition of the empire. Following Alexander’s death at the hands of his own soldiers, Rome plunged into a long period of uneasy, rapid successions referred to as the Crisis of the Third Century, a crisis that lasted for fifty years.

Soldier Emperors

The first 26 emperors of this period were generals who either proclaimed themselves or were officially acknowledged as the emperor. Their reigns lasted from a couple of months to a couple of years. The fact that they were all generals in the Roman army underscores the military insecurity of the empire at this time.

Instead of protecting the border or trade routes, legions of soldiers were often fighting each other in support of one emperor or another. Since Roman power was still centered in Rome, the only building project that succeeded through this period was the building and maintaining of the city’s Aurelian Wall, under the emperor Aurelian (r. 270–275 CE).

The portraits of Trajan Decius (r. 249–251 CE) and Trebonianus Gallus (r. 252–253 CE) serve to illustrate the instability of the period and the need for soldier-emperors to assert power to maintain some semblance of control.

Trajan Decius

Trajan Decius’s portrait at first seems to take its artistic style from Republican veristic portraiture, but a closer look reveals something else. Instead of depicting a hyper-realistic portrait of an old and wise man, this portrait reveals the anxiety and nervousness of the emperor. His brow is furrowed with worry and wrinkles, and his eyes and mouth impart a feeling of fear and anguish (see Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)).

Trebonianus Gallus

The portrait of his successor, Trebonianus Gallus takes a different style, relying on old sculpture and narrative conventions to depict the emperor as a contemporary hero. This larger-than-life bronze statue depicts a muscled, nude man with his right arm raised in a gesture of speech. He seems to be in adlocutio pose, addressing the troops or perhaps the people of Rome (see Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). His head is notably smaller than his torso and disproportional to his body. This places emphasis on his bulk and reminds the viewer of the emperor’s power and the stability he hoped to create.

Late Antique Art: The Ludovisi Sarcophagus

Sculpture during this period demonstrates the style and design of Late Antique art that was initially developed during the late second century CE from plebeian models. The emergence of the style corresponds with the social, political, and economic upheaval of the empire that began during the reign of Commodus. This style removes Classical conventions of realism. It pushes its characters into the foreground and almost entirely removes the background.

In the scenes shown on the Ludovisi Sarcophagus, the undercutting of the deep relief exhibits virtuosic and very time-consuming drill work that conveys chaos and a sense of weary, open-ended victory. It differs from earlier battle scenes on sarcophagi in which more shallowly carved figures are less convoluted and intertwined (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). Unlike earlier Roman depictions of warfare, this scene does not differentiate the general by his attire or engagement in battle. Rather, he is only slightly larger than the figures around him.

From the late second century, Roman art increasingly depicted battles as chaotic, packed, single-plane scenes that emphasize dehumanized barbarians who are subjected mercilessly to Roman military might, at a time when in fact the Roman Empire was undergoing constant invasions from external threats that led to the fall of the empire in the West. Although armed, the barbarian warriors, usually identified as Goths, are depicted as helpless to defend themselves.

After the Soldier Emperors

The Crisis of the Third Century continued after the reign of the Soldier Emperors as the title of emperor was auctioned off to the highest bidder by the Praetorian Guard and various men, not always generals, from around the empire seized power for brief periods of time. This process continued until the reign of Diocletian, beginning in 284 CE.

Portrait of Galerius

Galerius served in the Tetrarchy from 293 to 311 CE, beginning his career as the Caesar of the West (293–305) under Diocletian, and eventually rising to Augustus of the West (305–311) after Diocletian’s retirement. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sassanid (Neo-Persian) Empire, and sacked their capital in 299. He also campaigned across the Danube against the Carpi (in present-day eastern Romania), and defeated them in 297 and 300. He opposed Christianity and oversaw the carrying out of the Diocletianic Persecution, which rescinded the rights of Christians and ordered that they comply with traditional Roman religious practices. However, toward the end of his reign in 311, he issued an edict of toleration.

A porphyry bust of Galerius (c. 300 CE) shows the direction that portraiture was taking in the fourth century. This bust from the emperor’s palace features a face that is largely naturalistic with large expressive eyes and eyebrows, similar to those on the group portrait of the Tetrarchs, that lean toward abstraction (see Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). These attributes follow those of other sculptures of the Late Antique style and foreshadow the increasingly geometric form that facial features would assume in imperial portraiture and sculpture in general.

Constantine

Diocletian and his co-emperor Maximian abdicated power on May 1, 305 CE. However, over the course of the next five years, Maximian made several attempts to regain his title, and then committed suicide in 310. In the meantime, power passed to Maximian’s son Maxentius and Constantine, the son of a third co-emperor, Constantius.

Unfortunately for Diocletian’s legacy and the stability created by the Tetrarchy, a power struggle between the two heirs erupted a year after the former Augustus’ abdication. When Constantius died on July 25, 306, his father’s troops proclaimed Constantine as Augustus in Eboracum (York, England). In Rome, the favorite was Maxentius, who seized the title of emperor on October 28, 306. Galerius, ruler of the Eastern provinces and the senior emperor in the Empire, recognized Constantine’s claim and treated Maxentius as a usurper. Galerius, however, recognized Constantine as holding only the lesser imperial rank of Caesar.

Despite a mutiny against Galerius’ co-emperor Severus in 307, and Galerius’s subsequent failure to take Rome, Constantine managed to avoid conflict for most of this period. However, by 312, Constantine and Maxentius were engaged in open hostilities, culminating in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, in which Constantine emerged victorious. Although he attributed this victory to the aid of the Christian god, he did not convert to Christianity until he was on his deathbed. The following year, however, he enacted the Edict of Milan, which legalized Christianity and allowed its followers to begin building churches. With the Christian community growing in number and in influence, legalizing Christianity was, for Constantine, a pragmatic move.

Following a rebellion from Licinius, his own co-emperor in 324 CE, Constantine eventually had his former colleague executed and consolidated power under a single ruler. As the sole emperor of an empire with new-found stability, Constantine was able to patronize large building projects in Rome. However, despite his attention to that city, he moved the capital of the empire east to the newly founded city of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul).

Rome after Constantine

Following Constantine’s founding of a New Rome at Constantinople, the prominence and importance of the city of Rome diminished. The empire was then divided into east and west. The more prosperous eastern half of the empire continued to thrive, mainly due to its connection to important trade routes, while the western half of the empire fell apart.

While Byzantium controlled Italy and the city Rome at times over the next several centuries, for the most part the Western Roman Empire, due to being less urban and less prosperous, was difficult to protect. Indeed, the city of Rome was sacked multiple times by invading armies, including the Ostrogoths and Visigoths, over the next century. The multiple sackings of Rome resulted in the raiding of the marble, facades, décor, and columns from the monuments and buildings of the city. Parts of ancient Rome, especially the Republican Forum, returned once again to the cow pastures that they originally were at the time of the city’s founding, as floods from the Tiber washed them over in debris and sediment.

Constantinople

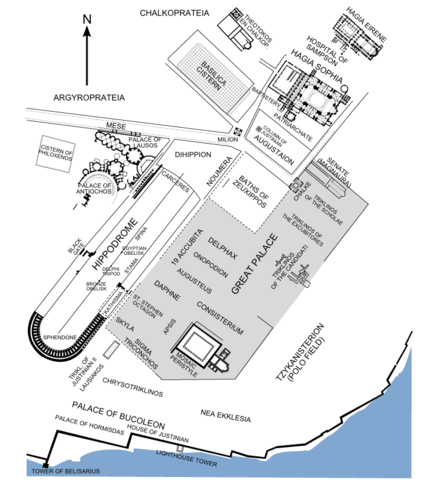

Constantine laid out a new square at the center of old Byzantium, naming it the Augustaeum. The new senate-house was housed in a basilica on the east side. On the south side of the great square was erected the Great Palace of the Emperor with its imposing entrance and its ceremonial suite known as the Palace of Daphne. Nearby was the vast Hippodrome for chariot races, seating over 80,000 spectators, and the famed Baths of Zeuxippus. At the western entrance to the Augustaeum was the Milion, a vaulted monument from which distances were measured across the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Mese, a great street lined with colonnades, led from the Augustaeum. As it descended the First Hill of the city and climbed the Second Hill, it passed the Praetorium or law-court. Then it passed through the oval Forum of Constantine where there was a second Senate house and a high column with a statue of Constantine in the guise of Helios, crowned with a halo of seven rays and looking toward the rising sun. From there the Mese passed on and through the Forum Tauri and then the Forum Bovis, and finally up the Seventh Hill (or Xerolophus) and through to the Golden Gate in the Constantinian Wall (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)).

A temple dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis in Southern Italy. Egyptian rulers depicted as both pharaohs and Greek kings. Mummies bearing Roman-style portraits. Although the textbook addresses Egypt, Greece, and Rome separately, there was considerable influence and exchange between these groups around the Mediterranean. It was not simply art objects that moved between empires, as Luigi Prada describes in “Multilingualism Along the Nile,” but also linguistic traditions, religious beliefs, and political ideologies that converged, resulting in a synthesis of rich cultural traditions.

The following article from the Getty Museum further explores such lasting artistic and cultural connections between the ancient Mediterranean world and Egypt.

Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World

Courtesy of the Getty Museum

Egypt was the oldest and most imposing civilization of the ancient world, renowned for its invention of writing, its monumental pyramids and temples, and its knowledge of history, astronomy, mathematics, magic, and medicine. Through this cultural prestige, as well as trade and diplomacy, Egypt exerted considerable influence on neighboring cultures throughout the Mediterranean, and was in turn affected by them. This exhibition explores the rich history of interconnections between Egypt, Greece and Rome over a span of more than two thousand years, from the Bronze Age to the Roman Imperial period.

Trade and gift exchange are the most visible features of early contacts in the centuries after 2000 BC, when Egyptian pharaohs sent stone vessels and other luxury goods to Minoan Crete and Mycenaean Greece, in return for silver bullion and scented oils in finely decorated pottery. Minoan artists even journeyed to Egypt to decorate a royal palace with Minoan-style frescoes. In the late seventh century BC, the Greeks were given permission by the pharaoh to establish a trading colony in the Nile Delta. The beginnings of monumental marble sculpture and architecture in Greece at this time manifest the clear impact of Egypt on the development of Greek art.

All previous interaction was overshadowed by Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt in 332 BC, ushering in nearly three centuries of Greek rule under the dynasty founded by his general Ptolemy. The subsequent mixing of Greek and Egyptian populations produced a diverse culture that embraced both local and foreign religious practices and artistic styles. After the Romans defeated the last Ptolemaic ruler, Cleopatra, in 31–30 BC, they absorbed Egypt into their empire as its richest province. Classical art had a strong effect on Egypt during this period, notably in funerary portraiture; and a fascination with all things Egyptian quickly spread throughout the Roman empire.

Download the exhibition object checklist

Egypt and the Aegean in the Bronze Age (2000–1100BC)

The Minoan civilization—named after the legendary king Minos—flourished on the island of Crete in 2000–1450 BCE. At a number of cities, including Knossos and Phaistos, newly constructed palaces were the center of religious rituals, artists’ workshops, and commerce. Minoan seafarers made their way to Egypt, trading silver, scented oil, and pottery for raw materials and luxury items that they brought back home. Some Egyptian objects appear to have reached Crete as royal gifts. These exchanges inspired both Egyptian and Minoan craftsmen to fashion imitations of each other’s wares, and mutual influence extended to religion and medicine (see Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)).

At the same time, the first Greek-speaking people were establishing kingdoms in mainland Greece, notably at Mycenae. Skilled in warfare, the Mycenaeans became the dominant power in the Aegean in 1500–1200 BC, taking control of Crete around 1450 BCE. They continued to trade with Egypt and offered their service as soldiers in the Egyptian army.

Waves of immigration and violent conflict throughout the eastern Mediterranean brought an end to the palace cultures of Greece, Anatolia (present-day Turkey), and much of the Levant (present-day Lebanon, Syria, and Israel) soon after 1200 BCE. Egypt, however, was able to resist invaders and survived the turbulent collapse that affected the rest of the region.

The Greeks Return to Egypt (700–332 BC)

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=329&height=500)

Contact between Greece and Egypt diminished following the collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms at the end of the Bronze Age (1200–1100 BC), but Greeks started returning to Egypt in the seventh century BCE. As before, they came as merchants and soldiers, and the Egyptian pharaohs, finding their services beneficial, allowed them to settle. Greek traders from Ionia (present-day western Turkey) and the islands of Rhodes and Aegina established an important colony at Naukratis, in the western Nile Delta. Although the Egyptians discouraged close relations with settlers, some Greeks rose to high positions in the royal court. The pharaoh Amasis II (ruled 570–527 BC) in particular was an admirer of the Greeks and married a Greek princess from the Greek city of Cyrene.

Greek artists were greatly inspired by the art and architecture they encountered in Egypt. Craftsmen in Naukratis and on the Greek islands learned to imitate Egyptian bronze figurines, faience vessels, and other small luxury objects, which were appreciated for their technical sophistication and exoticism. Sculptors in Greece began to create figural statues modeled on monumental Egyptian types, starting a process of invention and experimentation that would last centuries.

Ptolemaic Egypt (323–30 BC)

In 332 BC the Macedonian king Alexander the Great seized Egypt as part of his campaign to conquer the Persian Empire. After Alexander’s untimely death in 323 BC, control of Egypt passed to his general Ptolemy, who proclaimed himself king in 305 BC and established a dynasty that ruled for nearly three centuries, with fifteen successive monarchs each taking the same name. The Ptolemies maintained many of the existing political and religious institutions they found in Egypt but created a hybrid Greco-Egyptian culture. The new capital called Alexandria, on the Mediterranean coast, became the largest and wealthiest city of the Hellenistic Greek world, as well as a major center of learning.

The Ptolemies were famously extravagant and spared no expense in promoting themselves and their dynastic aspirations. Their portraits were disseminated through stone sculpture, gold and silver coins, and precious gems and cameos. Marble statues portrayed them as Greek kings and queens with individualized features, while dark stone figures and reliefs represented them as Egyptian pharaohs making offerings to local gods (see Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)).

Portraits of Egyptian Priests and Officials

Beginning around 2600 BC, Egyptian priests and high officials were honored with portrait statues displayed in temples and tombs.

A number of these works are strikingly naturalistic. While some might reflect actual appearances, many employ conventional mannerisms—such as corpulence, high cheekbones, pronounced eye sockets, and pursed lips—to impart a lifelike countenance. During Egypt’s Late Period (664–332 BC), sculptors conveyed individuality through irregularly shaped skulls, detailed eyes and ears, wrinkles at the corners of the eyes, furrowed brows, sagging flesh, and even scars and warts (see Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)). After the Greek conquest of Egypt, artists continued to produce vivid portraits in this tradition but sometimes added features showing contemporary Hellenistic influence.

Egypt and the Roman Empire (30 BC-300 CE)

The Roman general Octavian (the future emperor Augustus) brought Egypt under Roman rule with the defeat of Cleopatra VII and Marc Antony in 31–30 BCE. Like the Ptolemies before them, the Roman emperors often presented themselves as Egyptian pharaohs to the local people. The populace was now a mix of Egyptians and Greeks, many of whom were bilingual. They venerated gods of both cultures, and their religious and funerary art reflects this complex blend of ethnicities and influences.

The Romans marveled at the wealth, ancient traditions, and mysterious religion of the newly acquired land. Emperors brought obelisks and stone statues from Egypt to Rome to demonstrate their power as conquerors. Roman sculptures, paintings, mosaics, and luxury objects evoking Egyptian subjects and landscapes became immensely fashionable as decoration for villas. Deities such as Isis and Serapis gained popularity beyond Egypt and found worshippers throughout the Roman Empire.

Egypt and Southern Italy

Many works of art with Egyptian subjects have been found at Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabiae, and other sites around the Bay of Naples that were buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. Private villas were decorated with frescoes that evoked the people, landscape, and religion of Egypt. Statuettes and ritual implements discovered in some houses indicate that their occupants embraced the worship of Egyptian deities.

The cult of Isis enjoyed great popularity in southern Italy, and sanctuaries dedicated to the goddess proliferated throughout the region. A prominent temple of Isis in Pompeii contained Roman statues and wall paintings with Egyptian themes, as well as works imported from Egypt. During the reign of the emperor Domitian (AD 81–96), a large temple of Isis was established in the important city of Beneventum (present-day Benevento), northeast of Naples. It was ornamented with numerous sculptures carved from Egyptian stones, including two granite obelisks commemorating the ruler and the goddess (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)).

Egypt and Rome

Egyptian works of art reached Rome as early as the third century BC, first as royal gifts from the Ptolemies and then to satisfy wealthy Romans desiring exotic decoration for their homes. After the conquest of Egypt in 30 BC, the emperor Augustus brought back many spoils from the region as symbols of imperial triumph. Newly established temples in Rome dedicated to the deities Isis and Serapis displayed statues imported from Egypt as well as sculptures made in Italy in Egyptianizing style. Fascination with the recently annexed land encouraged the production of all manner of evocative images. Nilotic landscapes appeared on the frescoed walls of luxurious Roman villas; Egyptian motifs adorned furniture, silverware, and glass vessels; and sculpted Egyptian deities, crocodiles, and hippopotami populated private gardens.

Egyptianizing Sculpture from Hadrian's Villa

During the Roman emperor Hadrian’s visit to Egypt in AD 130–131, his companion Antinous tragically drowned in the Nile River. The grieving ruler memorialized his young lover by founding the city of Antinoopolis near the site of his death. He also established a Roman cult in which Antinous was honored as a semidivine hero and equated with Osiris, the Egyptian god of the underworld.

Hadrian’s lavish imperial villa at Tivoli, northeast of Rome, was decorated with numerous statues of Antinous in Egyptian costume, as well as many other sculptures with Egyptian imagery (see Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)). The enormous complex was designed to evoke the ruler’s wide-ranging travels throughout the Roman Empire. A terraced garden with a long pool was named Canopus after the site near Alexandria in Egypt, and a sanctuary that may have been dedicated to Antinous contained an obelisk in his memory.

Articles in this section:

- Boundless Art History, “The Decline of the Roman Empire.” (CC BY SA)

- The Getty Museum, "Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World." Used by permission.