11.4: High/Middle Empire

- Page ID

- 108665

During the approximately 100 years between the reign of Trajan and the assassination of the last Antonine emperor, Comodus (98-192 CE), the Roman Empire reached its greatest geographical extent. Despite ongoing fighting at its borders, the Empire's citizens largely continued to experience the peace and prosperity of the Pax Romana, leading to this period being called not just the Middle, but the High Empire.

The "CE" used in the date above stands for Common Era, which distinguishes it from dates marked BCE (Before the Common Era). The standard convention used by most historians is to include CE as part of the date reference for any works up to 150-200 years into the Common Era. For dates after that, the CE is generally dropped, and any dates without a CE or BCE reference are generally understood to be from the Common Era.

The Pantheon (Rome)

by Dr. Paul A. Ranogajec

The eighth wonder of the ancient world

The Pantheon in Rome is a true architectural wonder. Described as the “sphinx of the Campus Martius”—referring to enigmas presented by its appearance and history, and to the location in Rome where it was built—to visit it today is to be almost transported back to the Roman Empire itself. The Roman Pantheon probably doesn’t make popular shortlists of the world’s architectural icons, but it should: it is one of the most imitated buildings in history (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). For a good example, look at the library Thomas Jefferson designed for the University of Virginia.

Although the Pantheon’s importance is undeniable, there is a lot that is unknown. With new evidence and fresh interpretations coming to light in recent years, questions once thought settled have been reopened. Most textbooks and websites confidently date the building to the Emperor Hadrian’s reign and describe its purpose as a temple to all the gods (from the Greek, pan = all, theos = gods), but some scholars now argue that these details are wrong and that our knowledge of other aspects of the building’s origin, construction, and meaning is less certain than we had thought.

Whose Pantheon?—the problem of the inscription

Archaeologists and art historians value inscriptions on ancient monuments because these can provide information about patronage, dating, and purpose that is otherwise difficult to come by. In the case of the Pantheon, however, the inscription on the frieze—in raised bronze letters (modern replacements)—easily deceives, as it did for many centuries. It identifies, in abbreviated Latin, the Roman general and consul (the highest elected official of the Roman Republic) Marcus Agrippa (who lived in the first century BCE) as the patron: “M[arcus] Agrippa L[ucii] F[ilius] Co[n]s[ul] Tertium Fecit” (“Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, thrice Consul, built this”). The inscription was taken at face value until 1892, when a well-documented interpretation of stamped bricks found in and around the building showed that the Pantheon standing today was a rebuilding of an earlier structure, and that it was a product of Emperor Hadrian’s (who ruled from 117-138 CE) patronage, built between about 118 and 128. Thus, Agrippa could not have been the patron of the present building. Why, then, is his name so prominent?

The conventional understanding of the Pantheon

A traditional rectangular temple, first built by Agrippa

The conventional understanding of the Pantheon’s genesis, which held from 1892 until very recently, goes something like this. Agrippa built the original Pantheon in honor of his and Augustus’ military victory at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE—one of the defining moments in the establishment of the Roman Empire--Augustus would go on to become the first Emperor of Rome. It was thought that Agrippa’s Pantheon had been small and conventional: a Greek-style temple, rectangular in plan. Written sources suggest the building was damaged by fire around 80 CE and restored to some unknown extent under the orders of Emperor Domitian, who ruled 81-96 CE.

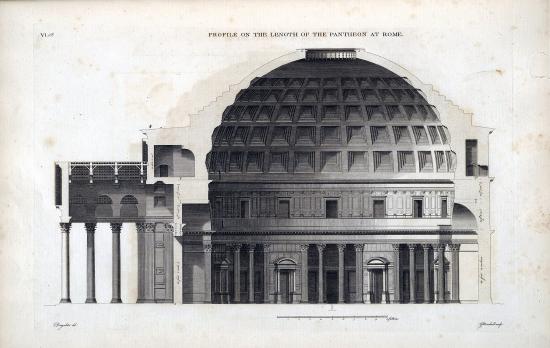

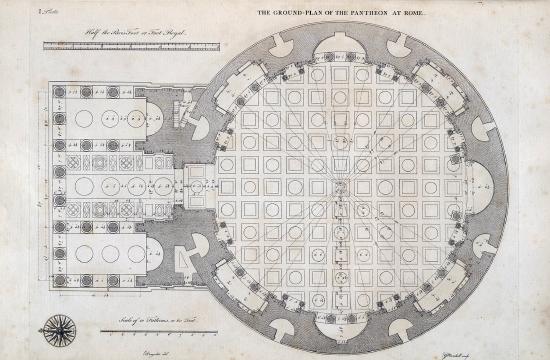

When the building was more substantially damaged by fire again in 110 CE, the Emperor Trajan decided to rebuild it, but only partial groundwork was carried out before his death. Trajan’s successor, Hadrian—a great patron of architecture and revered as one of the most effective Roman emperors—conceived and possibly even designed the new building with the help of dedicated architects. It was to be a triumphant display of his will and beneficence. He was thought to have abandoned the idea of simply reconstructing Agrippa’s temple, deciding instead to create a much larger and more impressive structure. And, in an act of pious humility meant to put him in the favor of the gods and to honor his illustrious predecessors, Hadrian installed the false inscription attributing the new building to the long-dead Agrippa. See rich details in the Pantheon's elevation plan (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), the photographic details of the Corinthian columns (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), Giovanni Paolo Panini's painting capturing the interior splendor of the Pantheon (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)), and the floor plan (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

New evidence—Agrippa’s temple was not rectangular at all

Today, we know that many parts of this story are either unlikely or demonstrably false. It is now clear from archaeological studies that Agrippa’s original building was not a small rectangular temple, but contained the distinctive hallmarks of the current building: a portico with tall columns and pediment and a rotunda (circular hall) behind it, in similar dimensions to the current building.

And the temple may be Trajan’s (not Hadrian’s)

More startling, a reconsideration of the evidence of the bricks used in the building’s construction—some of which were stamped with identifying marks that can be used to establish the date of manufacture—shows that almost all of them date from the 110s, during the time of Trajan. Instead of the great triumph of Hadrianic design, the Pantheon should more rightly be seen as the final architectural glory of the Emperor Trajan’s reign: substantially designed and rebuilt beginning around 114, with some preparatory work on the building site perhaps starting right after the fire of 110, and finished under Hadrian sometime between 125 and 128.

Lise Hetland, the archaeologist who first made this argument in 2007--building on an earlier attribution to Trajan by Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer, writes that the long-standing effort to make the physical evidence fit a dating entirely within Hadrian’s time shows “the illogicality of the sometimes almost surgically clear-cut presentation of Roman buildings according to the sequence of emperors.” The case of the Pantheon confirms a general art-historical lesson: style categories and historical periodizations (in other words, our understanding of the style of architecture during a particular emperor’s reign) should be seen as conveniences—subordinate to the priority of evidence.

What was it—a temple? A dynastic sanctuary?

It is now an open question whether the building was ever a temple to all the gods, as its traditional name has long suggested to interpreters. Pantheon, or Pantheum in Latin, was more of a nickname than a formal title. One of the major written sources about the building’s origin is the Roman History by Cassius Dio, a late second- to early third-century historian who was twice Roman consul. His account, written a century after the Pantheon was completed, must be taken skeptically. However, he provides important evidence about the building’s purpose. He wrote,

"He [Agrippa] completed the building called the Pantheon. It has this name, perhaps because it received among the images which decorated it the statues of many gods, including Mars and Venus; but my own opinion of the name is that, because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens. Agrippa, for his part, wished to place a statue of Augustus there also and to bestow upon him the honor of having the structure named after him; but when Augustus wouldn’t accept either honor, he [Agrippa] placed in the temple itself a statue of the former [Julius] Caesar and in the ante-room statues of Augustus and himself. This was done not out of any rivalry or ambition on Agrippa’s part to make himself equal to Augustus, but from his hearty loyalty to him and his constant zeal for the public good."

A number of scholars have now suggested that the original Pantheon was not a temple in the usual sense of a god’s dwelling place. Instead, it may have been intended as a dynastic sanctuary, part of a ruler cult emerging around Augustus, with the original dedication being to Julius Caesar, the progenitor of the family line of Augustus and Agrippa and a revered ancestor who had been the first Roman deified by the Senate. Adding to the plausibility of this view is the fact that the site had sacred associations—tradition stating that it was the location of the apotheosis, or raising up to the heavens, of Romulus, Rome’s mythic founder. Even more, the Pantheon was also aligned on axis, across a long stretch of open fields called the Campus Martius, with Augustus’ mausoleum, completed just a few years before the Pantheon. Agrippa’s building, then, was redolent with suggestions of the alliance of the gods and the rulers of Rome during a time when new religious ideas about ruler cults were taking shape.

The dome and the divine authority of the emperors

By the fourth century CE, when the historian Ammianus Marcellinus mentioned the Pantheon in his history of imperial Rome, statues of the Roman emperors occupied the rotunda’s niches. In Agrippa’s Pantheon these spaces had been filled by statues of the gods (see Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). We also know that Hadrian held court in the Pantheon. Whatever its original purposes, the Pantheon by the time of Trajan and Hadrian was primarily associated with the power of the emperors and their divine authority.

The symbolism of the great dome adds weight to this interpretation. The dome’s coffers, or inset panels, are divided into 28 sections, equaling the number of large columns below. 28 is a “perfect number,” a whole number whose summed factors equal it (thus, 1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14 = 28). Only four perfect numbers were known in antiquity (6, 28, 496, and 8128) and they were sometimes held—for instance, by Pythagoras and his followers—to have mystical, religious meaning in connection with the cosmos. Additionally, the oculus, or open window at the top of the dome was the interior’s only source of direct light (see Figures \(\PageIndex{7}\) and \(\PageIndex{11}\)). The sunbeam streaming through the oculus traced an ever-changing daily path across the wall and floor of the rotunda. Perhaps, then, the sunbeam marked solar and lunar events, or simply time. The idea fits nicely with Dio’s understanding of the dome as the canopy of the heavens and, by extension, of the rotunda itself as a microcosm of the Roman world beneath the starry heavens, with the emperor presiding over it all, ensuring the right order of the world.

How was it designed and built?

The Pantheon’s basic design is simple and powerful. A portico with free-standing columns is attached to a domed rotunda. In between, to help transition between the rectilinear portico and the round rotunda is an element generally described in English as the intermediate block. This piece is itself interesting for the fact that visible on its face above the portico’s pediment is another shallow pediment. This may be evidence that the portico was intended to be taller than it is (50 Roman feet instead of the actual 40 feet). Perhaps the taller columns, presumably ordered from a quarry in Egypt, never made it to the building site (for reasons unknown), necessitating the substitution of smaller columns, thus reducing the height of the portico (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)).

The Pantheon’s great interior spectacle—its enormous scale, the geometric clarity of the circle-in-square pavement pattern and the dome’s half-sphere, and the moving disc of light—is all the more breathtaking for the way one moves from the bustling square (piazza, in Italian) outside into the grandeur inside (see Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)).

One approaches the Pantheon through the portico with its tall, monolithic Corinthian columns of Egyptian granite. Originally, the approach would have been framed and directed by the long walls of a courtyard or forecourt in front of the building, and a set of stairs, now submerged under the piazza, leading up to the portico as shown in the recreation in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). Walking beneath the giant columns, the outside light starts to dim. As you pass through the enormous portal with its bronze doors, you enter the rotunda, where your eyes are swept up toward the oculus.

The structure itself is an important example of advanced Roman engineering. Its walls are made from brick-faced concrete—an innovation widely used in Rome’s major buildings and infrastructure, such as aqueducts—and are lightened with relieving arches and vaults built into the wall mass. The concrete easily allowed for spaces to be carved out of the wall’s thickness—for instance, the alcoves around the rotunda’s perimeter and the large apse directly across from the entrance (where Hadrian would have sat to hold court). Further, the concrete of the dome is graded into six layers with a mixture of scoria, a low-density, lightweight volcanic rock, at the top. From top to bottom, the structure of the Pantheon was fine-tuned to be structurally efficient and to allow flexibility of design.

Who designed the Pantheon?

We do not know who designed the Pantheon, but Apollodorus of Damascus, Trajan’s favorite builder, is a likely candidate—or, perhaps, someone closely associated with Apollodorus. He had designed Trajan’s Forum and at least two other major projects in Rome, probably making him the person in the capital city with the deepest knowledge about complex architecture and engineering in the 110s. On that basis, and with some stylistic and design similarities between the Pantheon and his known projects, Apollodorus’ authorship of the building is a significant possibility.

When it was believed that Hadrian had fully overseen the Pantheon’s design, doubt was cast on the possibility of Apollodorus’ role because, according to Dio, Hadrian had banished and then executed the architect for having spoken ill of the emperor’s talents. Many historians now doubt Dio’s account. Although the evidence is circumstantial, a number of obstacles to Apollodorus’ authorship have been removed by the recent developments in our understanding of the Pantheon’s genesis. In the end, however, we cannot say for certain who designed the Pantheon.

Why Has It Survived?

We know very little about what happened to the Pantheon between the time of Emperor Constantine in the early fourth century and the early seventh century—a period when the city of Rome’s importance faded and the Roman Empire disintegrated. This was presumably the time when much of the Pantheon’s surroundings—the forecourt and all adjacent buildings—fell into serious disrepair and were demolished and replaced. How and why the Pantheon emerged from those difficult centuries is hard to say. The Liber Pontificalis—a medieval manuscript containing not-always-reliable biographies of the popes—tells us that in the 7th century Pope Boniface IV “asked the [Byzantine] emperor Phocas for the temple called the Pantheon, and in it he made the church of the ever-virgin Holy Mary and all the martyrs.” There is continuing debate about when the Christian consecration of the Pantheon happened; today, the balance of evidence points to May 13, 613. In later centuries, the building was known as Sanctae Mariae Rotundae (Saint Mary of the Rotunda). Whatever the precise date of its consecration, the fact that the Pantheon became a church—specifically, a station church, where the pope would hold special masses during Lent, the period leading up to Easter—meant that it was in continuous use, ensuring its survival.

Yet, like other ancient remains in Rome, the Pantheon was for centuries a source of materials for new buildings and other purposes—including the making of cannons and weapons. In addition to the loss of original finishings, sculpture, and all of its bronze elements, many other changes were made to the building from the fourth century to today. Among the most important: the three easternmost columns of the portico were replaced in the seventeenth century after having been damaged and braced by a brick wall centuries earlier; doors and steps leading down into the portico were erected after the grade of the surrounding piazza had risen over time; inside the rotunda, columns made from imperial red porphyry—a rare, expensive stone from Egypt—were replaced with granite versions; and roof tiles and other elements were periodically removed or replaced. Despite all the losses and alterations, and all the unanswered and difficult questions, the Pantheon is an unrivaled artifact of Roman antiquity (see Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)).

Equestrian Sculpture of Marcus Aurelius

by Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker

In ancient Rome equestrian statues of emperors would not have been uncommon sights in the city—late antique sources suggest that at least 22 of these “great horses” (equi magni) were to be seen—as they were official devices for honoring the emperor for singular military and civic achievements. The statues themselves were, in turn, copied in other media, including coins, for even wider distribution.

Few examples of these equestrian statues survive from antiquity, however, making the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius a singular artifact of Roman antiquity, one that has borne quiet witness to the ebb and flow of the city of Rome for nearly 1,900 years (see Figures \(\PageIndex{13}\) and \(\PageIndex{14}\)). A gilded bronze monument of the 170s CE that was originally dedicated to the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, referred to commonly as Marcus Aurelius (reigned 161-180 CE), the statue is an important object not only for the study of official Roman portraiture, but also for the consideration of monumental dedications. Further, the use of the statue in the Medieval, Renaissance, modern, and post-modern city of Rome has important implications for the connectivity that exists between the past and the present.

Description

The statue is an over life-size depiction of the emperor elegantly mounted atop his horse while participating in a public ritual or ceremony; the statue stands approximately 4.24 meters tall. A gilded bronze statue, the piece was originally cast using the lost-wax technique, with horse and rider cast in multiple pieces and then soldered together after casting.

The horse

The emperor’s horse is a magnificent example of dynamism captured in the sculptural medium. The horse, caught in motion, raises its right foreleg at the knee while planting its left foreleg on the ground, its motion checked by the application of reins, which the emperor originally held in his left hand. The horse’s body—in particular its musculature—has been modeled very carefully by the artist, resulting in a powerful rendering. In keeping with the motion of the horse’s body, its head turns to its right, with its mouth opened slightly. The horse wears a harness, some elements of which have not survived. The horse is saddled with a Persian-style saddlecloth of several layers, as opposed to a rigid saddle. It should be noted that the horse is an important and expressive element of the overall composition.

The horseman

The horseman sits astride the steed, with his left hand guiding the reins and his right arm raised to shoulder level, the hand outstretched.

There are approximately 110 known portraits of Marcus Aurelius and these have been grouped into four typological groupings. The first two types belong to the emperor’s youth, before he assumed the duties of the principate (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)).

In the Roman world it was standard practice to create official portrait types of high-ranking officials, such as emperors that would then circulate in various media, notably sculpture in the round and coin portraits. These portrait types are vital in several respects, especially for determining the chronology of monuments and coins, since the portrait types can usually be placed in a fairly accurate and legible chronological order.

The interpretation of these portraits relies on various key elements, especially the reading of hairstyle and the examination of facial physiognomy. In the case of the equestrian statue, the portrait typology offers the best means of assigning an approximate date to the object since it does not otherwise offer another means of dating. The earliest portrait of Marcus Aurelius dates to c. 140 CE and is best represented by the Capitoline Galleria 28 type, where the youth wears a cloak fastened at the shoulder (paludamentum); this portrait was widely circulated, with approximately 25 known copies (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)).

The second portrait type was made when Marcus was in his late 20s, c. 147 CE, and shows a still youthful type, although Marcus now has light facial hair (see Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)).

Marcus Aurelius became emperor in 161 C.E., when he was forty years of age; this was the occasion for the creation of his third and most important portrait type. This mature type [not pictured] shows the emperor fully bearded with a full head of tightly curled, voluminous hair; he retains the characteristic oval-shaped face and heavy eyelids from his earlier portraits. His coiffure forms a distinctive arc over his forehead. This third type is known from approximately 50 copies.

The emperor’s fourth portrait type (see Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)), created between 170 and 180 CE, retains most of the features of the third type, but shows the emperor slightly more advanced in age with a very full beard that is divided in the center at the chin, showing parallel locks of hair.

The statue of the horseman is carefully composed by the artist and depicts a figure that is simultaneously dynamic and a bit passive and removed, by virtue of his facial expression (see Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\)). The locks of hair are curly and compact and distributed evenly; the beard is also curly, covering the cheeks and upper lip, and is worn longer at the chin. The pose of the body shows the rider’s head turned slightly to his right, in the direction of his outstretched right arm. The left hand originally held the reins (no longer preserved) between the index and middle fingers, with the palm facing upwards. Scholars continue to debate whether he originally held some attached figure or object in the palm of the left hand; possible suggestions have included a scepter, a globe, a statue of victory—but there is no clear indication of any attachment point for such an object. On the left hand the rider does wear the senatorial ring.

The rider is clad in civic garb, including a short-sleeved tunic that is gathered at the waist by a knotted belt (cingulum). Over the tunic the rider wears a cloak (paludamentum) that is clasped at the right shoulder. On his feet Marcus Aurelius wears the senatorial boots of the patrician class, known as calcei patricii.

Interpretation and chronology

The interpretation and chronology of the equestrian statue must rely on the statue itself, as no ancient literary testimony or other evidence survives to aid in the interpretation. It is obvious that the statue is part of an elaborate public monument, no doubt commissioned to mark an important occasion in the emperor’s reign. With that said, however, it must also be noted that scholars continue to debate its precise dating, the occasion for its creation, and its likely original location in the city of Rome.

Starting with the portrait typology it is possible to determine a range of likely dates for the statue’s creation. The portrait is clearly an adult type of the emperor, meaning the statue must have been created after 161 CE, the year of Marcus Aurelius’ accession and the creation of his third portrait type. This provides a terminus post quem (the limit after which) for the equestrian statue. Art historians have debated whether the portrait head most resembles the Type III or the Type IV portrait. Recent scholarly thinking, based on the work of Klaus Fittschen, holds that the equestrian portrait represents a unique variant of the standard Type III portrait, created as an improvisation by the artist who was commissioned to create the equestrian statue. In the end the precise chronology of the portrait head—and indeed the typology—remains a matter of scholarly debate.

The pose of the horseman is also helpful. The emperor stretches his right hand outward, the palm facing toward the ground; a pose that could be interpreted as the posture of adlocutio, indicating that the emperor is about to speak. However, more likely in this case we may read it as the gesture of clemency (clementia), offered to a vanquished enemy, or of restitutio pacis, the “restoration of peace.” Richard Brilliant has noted that since the emperor appears in civic garb as opposed to the general’s armor, the overall impression of the statue is one of peace rather than of the immediate post-war celebration of military victory. Some art historians reconstruct a now-missing barbarian on the right side of the horse, as seen in a surviving panel relief sculpture that originally belonged to a now-lost triumphal arch dedicated to Marcus Aurelius (see Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\)). We know that Marcus Aurelius celebrated a triumph in 176 CE for his victories over German and Sarmatian tribes, leading some to suggest that year as the occasion for the creation of the equestrian monument.

History

The original location of the equestrian monument also remains debated, with some supporting a location on the Caelian Hill near the barracks of the imperial cavalry (equites singulares), while others favor the Campus Martius (a low-lying alluvial plain of the Tiber River) as a possible location. A text known as the Liber Pontificalis that dates to the middle of the tenth century CE mentions the equestrian monument, referring to it as “caballus Constantini” or the “horse of Constantine.” According to the text, the urban prefect of Rome was condemned following an uprising against Pope John XII and, as punishment, was hung by the hair from the equestrian monument. At this time the equestrian statue was located in the Lateran quarter of the city of Rome near the Lateran Palace, where it may have been since at least the eighth century CE. Popular theories at the time held that the bearded emperor was in fact Constantine I, thus sparing the statue from being melted down.

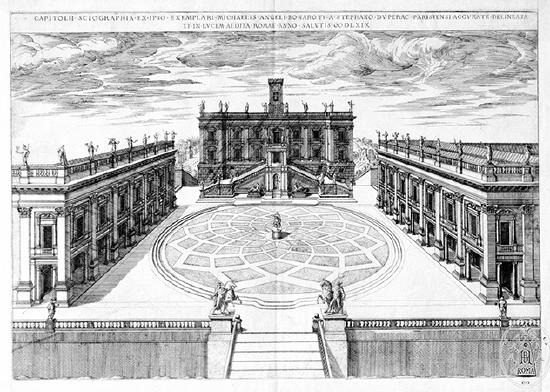

In 1538 the statue was relocated from the Lateran quarter to the Capitoline Hill to become the centerpiece for Michelangelo’s new design for the Campidoglio (a piazza, or public square, at the top of the Capitoline hill). The statue was set atop a pedestal at the center of an intricately designed piazza flanked by three palazzi (see Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)). It became the centerpiece of the main piazza of secular Rome and, as such, an icon of the city, a role that its still retains. The equestrian statue still plays a role as an official symbol of the city of Rome, even being incorporated into the reverse image of the Italian version of the € 0.50 coin (see Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\)). The statue itself remained where Michelangelo positioned it until it was moved indoors in 1981 for conservation reasons; a high-tech copy of the original was placed on the pedestal. The ancient statue is now housed within the Musei Capitolini where it can be visited and viewed today.

The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius is an enduring monument, one that links the city’s many phases, ancient and modern. It has borne witness to the city’s imperial glory, post-imperial decline, its Renaissance resurgence, and even its quotidian experience in the twenty-first century. In so doing it reminds us about the role of public art in creating and reinforcing cultural identity as it relates to specific events and locations. In the ancient world the equestrian statue would have evoked powerful memories from the viewer, not only reinforcing the identity and appearance of the emperor but also calling to mind the key events, achievements, and celebrations of his administration. The statue is, like the city, eternal, as reflected by the Romanesco poet Giuseppe Belli who reflects in his sonnet Campidojjo (1830) that the gilded statue is directly linked to the long sweep of Rome’s history.

At its height, the Roman Empire controlled territory from what is today Spain to Syria, Africa to England, all with a single government headquartered in the city of Rome. Across their expanding territory, the Romans built with remarkable consistency. This remained true even as they allowed conquered people to retain their own traditions and religion—as long as they also paid their taxes and paid homage to the state religion, in which the emperor was a god. Just as they borrowed architectural traditions from the Greeks, Romans also borrowed urban planning systems from them. Specifically, Rome adopted the Hippodamian grid plan for their colonial cities and castra (singular castrum), or military encampments. Named after Hippodamus, a 5th century Greek philosopher and urban planner from Miletus, the plan is based upon rigidly geometric urban planning using straight streets that cross at right angles and form regular city blocks, rather than unplanned, curved, and organic city layouts (see Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\)). Two main streets, one running north-south and one east-west, usually met at a forum or public square in the central part of town. Other recognizable, staple Roman structures and spaces were also part of the city plan, including theaters, markets, baths, and temples.

This city plan was important to Roman authority and control as they grew their colonies, both near and far, establishing an orderly and regularized system of organization. The standardized city plan, which disregards topography, or the natural forms and features of a land’s surface, could be disseminated easily, built from a precise model, and implemented almost anywhere. The imposed plan acted as a physical metaphor for the colonizers’ authority over a place and people, exerting order and control over geographical space, while also imposing cultural norms and values in the form of public buildings, markets, and ritual spaces. Protective strategies were often also included in the city’s design so that natural defenses were incorporated into the perimeter of the city. As more of these colonial cities were implemented, their familiarity and interchangeability meant that any arriving Roman traveler or soldier would immediately know where to find everything—contributing to even greater and more successful expansion. Roman colonial cities that used Hippodamian plans include Ephesus, Turkey (founded as a Roman colony in 27 BCE) and Timgad, Algeria (c. 100 BCE; (see Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\)). From Spain to Jordan, and many places in between, the imprint of the Roman Empire can still be seen.

Because of Rome’s colonial success, many other later colonizers such as Spain and Great Britain adopted similar strategies when expanding their own territories and planning new cities. During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, King Phillip II established laws and ordinances in 1573 to guide the planning and construction of colonial cities, requiring that principal streets meet centrally at a plaza. In 1836, British naval officer William Light implemented a complex, but similar grid-plan in Adelaide, South Australia, influenced by earlier Hippodamian plans and those of King Phillip II.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Paul A. Ranogajec, "The Pantheon (Rome)," in Smarthistory, December 11, 2015.

- Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, "Equestrian Sculpture of Marcus Aurelius," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015.