9.2: Geometric, Proto-Archaic, and Archaic

- Page ID

- 108624

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Dipylon Amphora: A Conversation

by Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

As tall as a person, this pot is covered with geometric patterns and early figural representations. This is the transcript of a conversation conducted at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Click to watch the video.

Steven: We’re in the National Archeological Museum in Athens looking at the Dipylon Vase.

Beth: The so-called Dipylon Vase because it was found near what would later become the Dipylon Gate in Athens and a cemetery right near there.

Steven: So this is a gigantic, ceramic pot. It’s an anaphora. But it would have been used as a grave marker in antiquity and it’s big. It’s five feet one inch tall.

Beth: Yeah, it’s almost as tall as I am. It’s unusual in that we see figures. We see a narrative scene and this is something that we see emerging more and more in the late geometric period. And geometric is such an obvious name for the style of this vase.

Steven: Well look at the vase, it’s covered from its foot all the way to the lip of its mouth with sharp-edged geometric patterns. I see meanders, I see diamonds, I see triangles. This is a pot coming out of that ancient tradition which really avoided empty space.

Beth: We do see black bands around the base where the neck meets the body and at the very lip of the vase. So we do have some black bands designating the separate parts of the vase.

Steven: But the most interesting part is the fact that we have emerging here representations of animals and even of people. As you said we only see that at the end of the geometric period.

Beth: On the neck of the vase we see deer grazing.

Steven: Below that we see what are either goats or gazelles perhaps or some people have said deer as well.

Beth: Lying down or seated.

Steven: But notice in both cases with the deer and with the goats, it’s really a repeated motif so that it is a continuation of that pattern that is so much a part even of the non-figurative areas of the pot.

Beth: It’s true in the bodies of the animals are reduced to geometric shapes, each one is exactly identical to the one before and the one after and they’re almost easy to miss as animal figures.

Steven: Because they are so much a part of the pattern of the pot.

Beth: Exactly.

Steven: But in the main phrase at the shoulder of the pot, almost at its widest point.

Beth: Right where the handles meet the body.

Steven: We see a number of mourning figures on either side of the body of a dead woman.

Beth: Now we know it’s a woman because she is wearing a skirt and different genders were identified in that way and she’s lying on a funeral bier with a shroud held above her.

Steven: You see figures pulling at their hair, this is a symbol of mourning. Some people have even interpreted the little M-shaped patterns falling between the figures as tears.

Beth: Look at how the artist has avoided leaving any space blank. Even between those M-shapes, he’s painted little star shapes to fill in the blank spaces.

Steven: Below the dead woman we can see perhaps the family. We see larger figures on their knees and then we see smaller figures, perhaps the children.

Beth: The bodies are upside down triangles. The legs are lozenges. Everything is very reduced and the figures are all rendered as black silhouettes. Now the Greeks had a very specific way of firing pots to get the red ground and the black figures above it.

Steven: So this is not glaze in the modern sense, instead this is slipware. So slip is fine particles of clay that are suspended in water and then painted on the surface of the pot. Now this was very difficult because when you painted on that slip it was the same color as the dry clay before it was fired. But then it was the next step that was important.

Beth: It was fired in a kiln at about 900 degrees.

Steven: That’s Celsius.

Beth: It was fired in a way where oxygen was withdrawn from the kiln. This causes the entire pot to turn black.

Steven: The kiln was then allowed to cool somewhat and then oxygen was allowed back into the kiln and then what happens is, the parts of the vase that are not painted return to their warm, red color and only the parts that were painted remain black. And so you can imagine how difficult this was to control in the ancient world before thermometers.

Beth: It really is an amazing testament to the skill of Greek potters.

Steven: Well the person who actually fashioned this pot produced it on a wheel but had to produce it in sections and then fit these sections together seamlessly.

Beth: This is a great example of late geometric Greek pottery.

Exekias, Attic Black Figure Amphora with Ajax and Achilles Playing a Game: A Conversation

by Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Achilles and Ajax, heroes of the Trojan War, break from battle to play a friendly game that hints at a tragic future. This is a transcript of a conversation conducted at the Etruscan Museum, Vatican, Rome.

Beth: I can see why it’s your favorite pot. It seems to almost glow.

Steven: You can see “tesara.”Beth: And on the right, we see Ajax, saying “three.”

Beth: We know immediately that Achilles is winning the game that they’re playing.

Steven: But this is, of course, a metaphor for the way that this myth will unfold.

Beth: On either side we see their shields. Achilles still has his helmet on, although Ajax has taken his off. So: a moment of relaxation between battles.

Steven: They’re on the battlefield of Troy, but Exekias has given us even more information than this, not simply the rolls of the dice, but in a larger sense, their fate. Look at the way, for example, that while both figures are hunched over and clearly focused on the game at hand–and remember, these two men are really close friends, so there’s an intimacy here, brotherhood—nevertheless, Achilles, who has the higher roll, is holding his spears loosely. You can see the way the points are actually separating. At the bottom, you can see from the lines, they’re not as parallel. But look at the figure on the right, Ajax, whose spears are held in a more parallel way, so that we know that he’s actually clenching with his fist, he’s tense.

Beth: I even sense a little bit of that tension in his brow.

Steven: That’s right. If you look at the brow really closely, you can see that Achilles has a single incised line to represent his eyebrow, but Ajax has a double line and it is a subtle clue that perhaps there’s a little bit of tension there. One other detail that can be easily seen, although it’s really subtle: look at the feet of both figures. Achilles, again, is relaxed. His heel is on the ground line, but Ajax, his heel is picked up ever so slightly, so you can see just a little bit of light underneath it, which means his calf is engaged, those muscles are tense, his body is tense.

Beth: He’s also a little bit more hunched over. His head is a little bit lower than that of his friend Achilles. That does seem to mean something wider than just this board game.

Steven: Anybody who was looking at this pot in the ancient world would have known the story of Ajax and Achilles that Homer tells, as you said, in the Iliad. Achilles is a great hero. In fact, as a child, his mother dipped him in the river Styx, which had the magical quality of making him invincible. It’s just that she held him by his heel, so his heel was not protected and ultimately, he would be killed by an arrow that hits him there.

Beth: Hence the term that we use often of someone’s Achilles heel, that is, their vulnerable spot.

Steven: Nevertheless, Achilles will die a great hero. Ajax will have a more complicated fate. He will outlive Achilles, and he will carry his great friend off the battlefield, but ultimately, he’ll be in a battle for Achilles’ armor.

Beth: Achilles had very special armor, which had been made by the god Hephaestus, the god of the forge.

Steven: Two people would want that armor, and they would both give speeches to convince judges as to who should get the armor, but Ajax, although he was much closer to Achilles, would lose the contest, have a bad moment where he slayed a bunch of Greeks, and ultimately, would kill himself on his own sword. Humiliation at the end of his life.

Beth: It’s really interesting to think about this as an ancient Greek viewer who knows that whole story and what will unfold for both of these heroes, but the story is one thing and the way that Exekias, the potter, has represented this moment and these two figures with so much nobility, with such fine detail in the shape of a vase, which is so elegant, is something else.

Steven: Exekias really was the great master of Attic black-figure vase painting. These are black figures, they are silhouettes. If you look closely, the decorative forms is mostly incised with a needle.

Beth: And the black surface is like paint, but it’s not quite paint.

Steven: This is slipware. Now, the Greeks didn’t have the technology to get kiln ovens hot enough to vitrify, that is to create true glazes, the way ceramics do now. What they would do instead is they would take very fine particles of clay, suspend them in water, and use those as a kind of paint. Depending on the amount of oxygen that they allowed into a kiln, they could turn it black or red. They would paint the surface with this slip and then they would burnish it. That is, they would take a very smooth surface, imagine the back of a spoon, and they would rub it back and forth so you get this surface that is really glossy and it almost looks like glaze.

Beth: When I look closely at the decorative borders on the handles or the decorative border just above the frieze of figures, I can see beautiful detail and the almost three-dimensional form of the slip is almost raised in areas, so it catches the light.

Steven: The Greeks did often use a syringe to paint the finest lines onto the surface, so one could imagine almost decorating a cake. You have a kind of syringe and you have the icing and it leaves a kind of bead that is raised against the surface and at a much finer level, that’s what we’re seeing here.

Beth: So Exekias is a master. His pots stand out in so many ways in their shape, in the painting, in the detail, in the drama that he was able to convey.

Steven: Certainly the Etruscans thought that was the case, because they must have spent a good deal of money importing this pot from Greece, across the Mediterranean, all the way to the Italian peninsula where they lived. So many of the great pots from ancient Greece are actually buried in Etruscan tombs. They were imported. The Greeks did a tremendous business exporting such pots, but Exekias was one of the great masters.

Sculpture in the Archaic Period

By Lumen Learning

Sculpture in the Archaic Period developed rapidly from its early influences, becoming more natural and showing a developing understanding of the body, specifically the musculature and the skin. Close examination of the style’s development allows for precise dating.

Most statues were commissioned as memorials and votive offerings or as grave markers, replacing the vast amphora (two-handled, narrow-necked jars used for wine and oils) and kraters (wide-mouthed vessels) of the previous periods, yet still typically painted in vivid colors.

Kouroi

Kouroi statues (singular, kouros), depicting idealized, nude male youths, were first seen during this period (see Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Carved in the round , often from marble, kouroi are thought to be associated with Apollo; many were found at his shrines and some even depict him. Emulating the statues of Egyptian pharaohs, the figure strides forward on flat feet, arms held stiffly at its side with fists clenched. However, there are some importance differences: kouroi are nude, mostly without identifying attributes and are free-standing.

Early kouroi figures share similarities with Geometric and Orientalizing sculpture, despite their larger scale. For instance, their hair is stylized and patterned, either held back with a headband or under a cap. The New York Kouros strikes a rigid stance and his facial features are blank and expressionless. The body is slightly molded and the musculature is reliant on incised lines.

As kouroi figures developed, they began to lose their Egyptian rigidity and became increasingly naturalistic. The kouros figure of Kroisos, an Athenian youth killed in battle, still depicts a young man with an idealized body (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). This time though, the body’s form shows realistic modeling.

The muscles of the legs, abdomen, chest and arms appear to actually exist and seem to function and work together. Kroisos’s hair, while still stylized, falls naturally over his neck and onto his back, unlike that of the New York Kouros, which falls down stiffly and in a single sheet. The reddish appearance of his hair reminds the viewer that these sculptures were once painted.

Archaic Smile

Kroisos’s face also appears more naturalistic when compared to the earlier New York Kouros. His cheeks are round and his chin bulbous; however, his smile seems out of place. This is typical of this period and is known as the Archaic smile. It appears to have been added to infuse the sculpture with a sense of being alive and to add a sense of realism.

Kore

A kore (plural korai) sculpture depicts a female youth (see Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). Whereas kouroi depict athletic, nude young men, the female korai are fully-clothed, in the idealized image of decorous women. Unlike men—whose bodies were perceived as public, belonging to the state—women’s bodies were deemed private and belonged to their fathers (if unmarried) or husbands.

However, they also have Archaic smiles, with arms either at their sides or with an arm extended, holding an offering. The figures are stiff and retain more block-like characteristics than their male counterparts. Their hair is also stylized, depicted in long strands or braids that cascade down the back or over the shoulder.

The Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE) depicts a young woman wearing a peplos, a heavy wool garment that drapes over the whole body, obscuring most of it. A slight indentation between the legs, a division between her torso and legs, and the protrusion of her breasts merely hint at the form of the body underneath.

Remnants of paint on her dress tell us that it was painted yellow with details in blue and red that may have included images of animals. The presence of animals on her dress may indicate that she is the image of a goddess, perhaps Artemis, but she may also just be a nameless maiden.

Later korai figures also show stylistic development, although the bodies are still overshadowed by their clothing. The example of a Kore (520–510 BCE) from the Athenian Acropolis shows a bit more shape in the body, such as defined hips instead of a dramatic belted waistline, although the primary focus of the kore is on the clothing and the drapery. This kore figure wears a chiton (a woolen tunic), a himation (a lightweight undergarment), and a mantle (a cloak). Her facial features are still generic and blank, and she has an Archaic smile. Even with the finer clothes and additional adornments such as jewelry, the figure depicts the idealized Greek female, fully clothed and demure.

Pedimental Sculpture: The Temple of Artemis at Corfu

This sculpture, initially designed to fit into the space of the pediment, underwent dramatic changes during the Archaic period, seen later at Aegina. The west pediment at the Temple of Artemis at Corfu depicts not the goddess of the hunt, but the Gorgon Medusa with her children; Pegasus, a winged horse; and Chrysaor, a giant wielding a golden sword surrounded by heraldic lions (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)).

Medusa faces outwards in a challenging position, believed to be apotropaic (warding off evil). Additional scenes include Zeus fighting a Titan, and the slaying of Priam, the king of Troy, by Neoptolemos. These figures are scaled down in order to fit into the shrinking space provided in the pediment.

Pedimental Sculpture: The Temple of Aphaia at Aegina

Sculpted approximately one century later, the pedimental sculptures on the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina gradually grew more naturalistic than their predecessors at Corfu (see Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)). The dying warrior on the west pediment (c. 490 BCE) is a prime example of Archaic sculpture. The male warrior is depicted nude, with a muscular body that shows the Greeks’ understanding of the musculature of the human body. His hair remains stylized with round, geometric curls and textured patterns.

However, despite the naturalistic characteristics of the body, the body does not seem to react to its environment or circumstances. The warrior props himself up with an arm, and his whole body is tense, despite the fact that he has been struck by an arrow in his chest. His face, with its Archaic smile, and his posture conflict with the reality that he is dying.

Aegina: Transition between Styles

The dying warrior on the east pediment (c. 480 BCE) marks a transition to the new Classical style (see Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)). Although he bears a slight Archaic smile, this warrior actually reacts to his circumstances. Nearly every part of him appears to be dying.

Instead of propping himself up on an arm, his body responds to the gravity pulling on his dying body, hanging from his shield and attempting to support himself with his other arm. He also attempts to hold himself up with his legs, but one leg has fallen over the pediment’s edge and protrudes into the viewer’s space. His muscles are contracted and limp, depending on which ones they are, and they seem to strain under the weight of the man as he dies.

Statue of a woman (Lady of Auxerre): A Conversation

By Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted in the Musée du Louvre, Paris. Click to watch the video.

Steven: We’re in the Louvre, in Paris, and we’re looking at a small, free-standing sculpture—a figure that’s often known as the Lady of Auxerre.

Beth: This is a Greek figure, likely from the island of Crete, but she was found, hence her title, in the French city of Auxerre, in the basement of a municipal museum. So we really don’t know about her findspot (the location where the object was originally excavated).

Steven: There’s some conjecture that she may have come originally from a cemetery in Crete, which would mean that she was a funerary sculpture, but we’re not sure. It’s possible that she was a votive figure, that is, a figure that was meant to honor the gods. And some scholars have even suggested that she might be a goddess herself.

Beth: This period, in the seventh century, is referred to as the Daedalic. And that name comes from the legendary sculptor Daedalus, who was said to be from the island of Crete.

Steven: This is a stylistic period that comes before the Archaic and parallels the Orientalizing style in ceramic decoration.

Beth: And in so many ways, she really does seem to prefigure the Archaic figures that we call kore: freestanding female figures that were sometimes representations of goddesses, sometimes votive figures (offerings to the gods)… This columnar (resembling a column) female figure who is very frontally oriented.

Steven: And abstracted. Her head is flattened, the face is relatively flat, the eyes are almond shaped.

Beth: “Flattened” is a good word here, because the front of her body appears flattened–although we do see her breasts—and even her hair has a flattened effect on either side of her face, and the top of her head also seems flattened.

Steven: But these are not unique characteristics to this sculpture. This is consistent with other sculptures of this period and of this area.

Beth: This is carved out of limestone. We’re used to seeing Greek sculptures as white marble, but we now know that these sculptures were generally brightly painted.

Steven: One of the most delicate aspects is the incising (lines cut into the stone). And we can see it most obviously in the square patterns in the front of her dress, but you can also make it out in the wrap that she wears around her shoulders and that move down one side of her arm.

Beth: And you can also make it out in the very wide belt that she wears and even in that collar underneath the shawl. What strikes me is that this is a very idealized figure; this is not meant to be a portrait of the deceased person whose grave this may have marked. This is a figure shown, very much like later Greek figures in the Archaic and Classical period, at the prime of life. She is beautiful, she’s young, she looks strong and healthy. Her waist is very narrow… She’s very feminine.

Steven: And the corners of her mouth are upturned in an expression that is sometimes referred to as the “Archaic smile,” even though this is before the Archaic period. Some art historians have conjectured that this may be an expression of well-being, of happiness, or perhaps a kind of transcendence. She feels so formal. Her feet are together.

Beth: That hand, in front…the other hand, that seems almost glued to the side of her body. But, unlike, earlier Egyptian figures, she’s freed from the stone. We have space between her body and her arms, which is an important part of this very early Greek tradition, which we’ll see in Archaic Greek art. And despite all the abstraction in her body that we just talked about, there’s something very lifelike about her, especially in her face. And I think that would have been even more true when she was painted; if we imagine the pink of her lips, or painted pupils in her eyes, or her hair painted brown…

Steven: One of the reasons that a figure like this fascinates art historians is because we know what happens next. She stands at the beginning of this long history of Greek sculpture, which reaches levels of brilliance that we’ve admired for thousands of years after. We’re seeing an early figure here, but one that, with all of the hindsight that we have, offers extraordinary promise.

Black Figures in Classical Greek Art

by Dr. Sarah Derbew. This essay first appeared in the Iris (CC BY 4.0).

In ancient Greece, men often escaped their daily grind to socialize at a symposium, or formalized drinking party. In the symposium, revelers indulged in numerous leisure activities centered around the consumption of wine. Among the variety of ceramic vessels that were used, pitchers of many shapes and sizes enabled wine pourers to fill the drinkers’ cups. [1] One example is this oinochoe, a type of wine jug, now on display in the new Athenian vases gallery at the Getty Villa (see Figures \(\PageIndex{16}\) and \(\PageIndex{17}\)).

Label text: "Pitcher in the Form of the Head of an African Man. Greek, made in Athens, about 510 BCE. Terracotta. Oinochoe attributed to Class B bis (Class of Louvre H 62) as potter. There were marked distinctions of status between those drinking at the symposion and thoes who catered to their needs. Occasional scenes on Athenian vases show Africans as slaves, and this stereotyped representation combines servant with serving vessel."

This head-shaped wine pitcher invites numerous questions. The first is, quite simply, how to describe it. How can curators responsibly and comprehensively create a label for this pitcher? Is this face best characterized as “black,” “African,” or “black-glazed”?

The term “black” is unsuitable, because it transports our modern color politics into antiquity; the Trans-Atlantic slave trade has permanently mangled any attempt to use this color objectively.

The geographical marker “African” initially seems like a sound alternative. Unlike the historical weight of “black,” using the name of a continent seems to sidestep the retrojection of slavery’s violent history. It also presents a utopian description that unites fifty-four countries and millions of people into a collective entity. To use the word “African” for this pitcher, however, is to irresponsibly project contemporary concerns onto the past. The notion of “Africa” was vague at the time of production of this vessel, around 500 B.C.E.; the Greek term for the region, “Libya,” referred generally to the northern and northeast regions of the continent. “Aithiopian” was another popular term used to describe people with black skin; the etymology of Aithiopia highlights this relationship: aithō (I blaze) + ops (face).

What about our third option to describe this vessel, “black-glazed”? This term softens modern racial thinking by enabling a focus on material composition; the description recognizes color but does not subscribe to any color-based hierarchy. Although it is naïve to imagine that the black-glazed face, paired with full lips and a broad nose, does not evoke comparison with real people, I would argue that “black-glazed” is preferable because it extends beyond its modern politicized counterpart, “Black.”[2] The hyphen emphasizes its artificial status; the label reflects artistic license rather than historical prejudices.

Now let us contextualize the description of this pitcher. The Getty Villa’s label tells us that “occasional scenes on Athenian vases show Africans as slaves, and this stereotyped representation combines servant and serving vessel.” Art historian François Lissarrague also interprets the black-glazed faces on other drinking cups and pitchers as servants in the symposium. [3]

Some literary evidence supports this claim; one of the character sketches in the late fourth century B.C.E. Theophrastus’ Characters describes a black person as an exotic servant for a petty man.[4] But other ancient Greek texts contradict this characterization; Homeric epics describe black people as semi-divine creatures whose country was a relaxing oasis for the gods.[5] Furthermore, visual references on ancient Greek vases depict black people in numerous roles: political allies, musicians, religious worshippers, soldiers, and servants. [6]

It is dangerous to fold selective history into the discussion without any reflective comments about the speculative work at play here. Although it is plausible that some black people were slaves in the fifth century B.C.E., there is no sure sign that this was the case in all situations.

The need for careful treatment of black people in ancient Greek art extends beyond this pitcher. On the cover of Roman historian Benjamin Isaac’s 2004 book The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, a troubling scene encourages anachronistic interpretations.

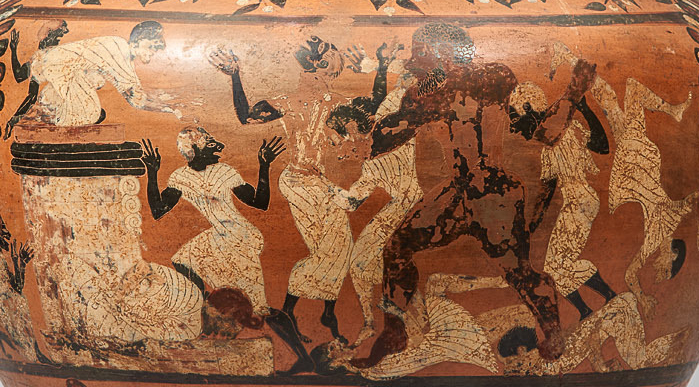

Here, we are confronted with a depiction of a violent encounter between a man and six other men. The person in the middle of the scene looms large and distinct; his upright pose and stark nakedness stand in sharp contrast to the clothed people in contorted positions around him. There are other visual clues that suggest his dominance. All of the men who come into contact with him either writhe under his feet or are firmly in his grasp. They are no match for his strength; he plows through them without hesitation.

Perhaps in collaboration with Isaac, Princeton University Press (the publishers of this book) chose this image as a cover for an important contribution to the discussion of racism in antiquity. This artistic rendition is based on a modern illustration of a sixth-century B.C.E. black-figure hydria, or water jar (see Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)). [7]

The impressive vase in Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\) can be seen at the Getty Center in the exhibition Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World. It depicts Herakles as he resists Egyptians’ attempts to sacrifice him under the orders of the Egyptian king Bousiris. According to ancient Greek mythology, Bousiris received a prophecy that stipulated the sacrifice of a foreigner in order to stop a drought that was destroying his city. When Herakles entered Egypt, Bousiris tried to slaughter him, but the Greek hero fought back and eventually escaped.

Although the visual similarities between the cover in Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\) and the water vessel in Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\) are striking, the ancient image allows for a more sophisticated approach to skin color than the book cover’s partial rendering of the scene. On the vase, black skin is capacious and flexible; it is not limited to those near Herakles. The crouching Egyptian priest on the left of the altar, as well as the Egyptian with raised hands to the right of the altar, have black skin. The black lines framing the scene and the black patterned designs on opposite sides of the scene also destabilize any quick interpretation of this color in antiquity. Skin color is only one element of this scene; the main theme appears to be the inverted violence that has occurred. The fear of the nine men is palpable; one has even climbed on top of the altar meant for Herakles. To add a final twist, Herakles’ skin tone on this jar is dark red. [8] Herakles’ blackness, as it appears today, is due to the worn state of the jar’s surface.

There are numerous examples of this sacrificial scene on ancient Greek pottery. Another depiction portrays Herakles as a figure whose skin color does not differ from those around him .

On the fifth-century B.C.E.greece storage jar in Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\), Herakles (on the left of the altar) again uses his sheer strength to punish the Egyptians. But there is a different awareness of color dynamics at play on this jar. Rather than a depiction of Herakles with black skin, blackness dominates the background of this vessel. Herakles’ black hair and black beard set him apart from the bald and clean-shaven Egyptians. This does not mean, however, that his chromatic appearance is particularly important in this scene. Instead, blackness literally fades into the background. It offers a visual palette for a powerful scene rather than a reflection of color-based power dynamics. Herakles’ lion-skin cloak and club are more helpful indicators of his identity. [9] In addition, the physiognomy of Herakles marks him as distinct from the Egyptians; his long nose and thin lips stand in contrast to their broad noses and full lips.

Altogether, it is undeniable that the image on Isaac’s cover reproduces an ancient representation of Herakles. But the cover art is also eerily reminiscent of contemporary discourse about Blackness. In particular, it suggests a dangerous connection between violence and the (modern) Black male body. This cover misleads anyone interested in ancient discussions of black skin because the contents of this book do not adequately address this topic. This omission encourages viewers and readers to assume that this image is an accurate representation of black people in Greek antiquity. Barring the caption on the back of the book, the image is presented without any context; people who judge books by their covers will jump to inaccurate conclusions. The permanently violent coding of black skin color is incorrect and irresponsible; there are no historical roots tracing this presumed innate threat.

In sum, museum and academic scholars are key players in the fight for contextualized and equitable perspectives of black people in antiquity; they curate exhibits and write books that greatly influence vast audiences. Preconceived notions of Black people are seared into our country’s collective consciousness; without an overhaul of the “black=slaves in perpetuity” trope, damaging stereotypes become ossified as facts for future generations. This brief examination has revealed ancient Greek art to be an expansive landscape. Ancient Greece’s visual heritage included representations of black people that nimbly provoked and cut across hierarchies. Objects like the sixth-century B.C.E. head-shaped pitcher and water jar discussed above were not part of any chromatic hierarchy because such categories had yet to be codified. Instead, they existed within their own historical and artistic context.

Notes:

- Various types of head-shaped vessels were produced around this time; see this example in the form of a woman’s head in the Getty Villa collection.

- I use “Black” to refer to the contemporary, socially constructed group of people, and “black” to designate people who are described as having black skin in ancient Greek literature and art.

- François Lissarrague, “Athenian Image of the Foreigner,” translated by Antonia Nevill. In Thomas Harrison, ed., Greeks and Barbarians (Routledge Press, 2002): 108–9.

- Theophrastus, 21.4.2.

- Iliad 1.423, Odyssey, 1.22-23.

- For more examples, see Frank Snowden Jr. “Aithiopes,” in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, Volume I: Aara-Aphlad (Artemis Publishers, 1981): 415-18.

- For a clearer rendition of the colors on this jar, see Perseus Digital Library.

- Jaap M. Hemelrijk, Caeretan Hydriae (Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1984): 52-54.

- Herakles killed and skinned a lion during the first of his Twelve Labors (feats he completed to atone for his madness-induced murder of his family)

Just as Dr. Sarah Derbew introduces the complexity of Black and African figures depicted in Classical Greek vessels and art, other cultures globally have also documented cultural interactions and political hierarchies through complex imagery painted on their drinking vessels. In Politics and History on a Maya Vase, Dr. Cara Grace Tremain discusses the importance of Mayan visual communication via serving vessels. In one particularly exquisite example from c. 650-750 CE called Painted Vessel (Enthroned Maya Lord and Attendants), Tremain points out the ways in which the scenes on this vessel reinforced Mayan political rule through imagery that showcased the Mayan royal court. On this vessel, the ruler is emphasized, sitting on his raised throne in the center and flanked by attendants who sit beside him and serve him from beneath. Such intricate vessels were reserved for the elite and used during communal feasts, which Tremain notes were not simply celebrations but were also political events that helped to unify and bolster relationships between different Maya city-states. These vessels were also gifted and traded, thus visually enforcing the importance of the ruler and Mayan royal court through aesthetically desirable finery.

In just over one minute, this video situates the Archaic Greek objects from this chapter among artworks from other cultures around the world. The Lady of Auxerre and New York Kouros, for example, come after the Assyrian Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions and before the Zhou Dynasty inner coffin from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng.

Smarthistory, "Tiny Timeline: Archaic Greece in a Global Context"

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, "Dipylon Amphora," in Smarthistory, December 14, 2015. (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Exekias, Attic black figure amphora with Ajax and Achilles playing a game," in Smarthistory, December 9, 2015. (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Boundless Art History, “Sculpture in the Archaic Period.” (CC BY-SA)

- Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, "Lady of Auxerre," in Smarthistory, December 14, 2015. (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Sarah Derbew, "Black Figures in Classical Greek Art," in Smarthistory, June 27, 2020. (CC BY-NC-SA)