9.1: Introduction- The Ancient Greeks and Their Gods

- Page ID

- 108619

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction to ancient Greek art

by Dr. Renee M. Gondek

A shared language, religion, and culture

Ancient Greece can feel strangely familiar. From the exploits of Achilles and Odysseus, to the treatises of Aristotle, from the exacting measurements of the Parthenon to the rhythmic chaos of the Laocoön (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)), ancient Greek culture has shaped our world. Thanks largely to notable archaeological sites, well-known literary sources, and the impact of Hollywood (Clash of the Titans, for example), this civilization is embedded in our collective consciousness—prompting visions of epic battles, erudite philosophers, gleaming white temples, and limbless nudes (we now know the sculptures—even the ones that decorated temples like the Parthenon—were brightly painted, and, of course, the fact that the figures are often missing limbs is the result of the ravages of time).

Dispersed around the Mediterranean and divided into self-governing units called poleis or city-states, the ancient Greeks were united by a shared language, religion, and culture. Strengthening these bonds further were the so-called “Panhellenic” sanctuaries and festivals that embraced “all Greeks” and encouraged interaction, competition, and exchange (for example the Olympics, which were held at the Panhellenic sanctuary at Olympia). Although popular modern understanding of the ancient Greek world is based on the classical art of fifth century BCE Athens, it is important to recognize that Greek civilization was vast and did not develop overnight.

The Dark Ages (c. 1100–c. 800 BCE) to the Orientalizing Period (c. 700–600 BCE)

Following the collapse of the Mycenaean citadels of the late Bronze Age, the Greek mainland was traditionally thought to enter a “Dark Age” that lasted from c. 1100 until c. 800 BCE. Not only did the complex socio-cultural system of the Mycenaeans disappear, but also its numerous achievements (i.e., metalworking, large-scale construction, writing). The discovery and continuous excavation of a site known as Lefkandi, however, drastically alters this impression. Located just north of Athens, Lefkandi has yielded an immense apsidal structure (almost fifty meters long), a massive network of graves, and two heroic burials replete with gold objects and valuable horse sacrifices. One of the most interesting artifacts, ritually buried in two separate graves, is a centaur figurine (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). At fourteen inches high, the terracotta creature is composed of a equine (horse) torso made on a potter’s wheel and hand-formed human limbs and features. Alluding to mythology and perhaps a particular story, this centaur embodies the cultural richness of this period.

Similar in its adoption of narrative elements is a vase-painting likely from Thebes dating to c. 730 BCE (see Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Fully ensconced in the Geometric Period (c. 800-700 BCE), the imagery on the vase reflects other eighth-century artifacts, such as the Dipylon Amphora, with its geometric patterning and silhouetted human forms. Though simplistic, the overall scene on this vase seems to record a story. A man and woman stand beside a ship outfitted with tiers of rowers. Grasping at the stern and lifting one leg into the hull, the man turns back towards the female and takes her by the wrist. Is the couple Theseus and Ariadne? Is this an abduction? Perhaps Paris and Helen? Or, is the man bidding farewell to the woman and embarking on a journey as had Odysseus and Penelope? The answer is unattainable.

In the Orientalizing Period (700-600 BCE), alongside Near Eastern motifs and animal processions, craftsmen produced more nuanced figural forms and intelligible illustrations. For example, terracotta painted plaques from the Temple of Apollo at Thermon (c. 625 BCE) are some of the earliest evidence for architectural decoration in Iron Age Greece. Once ornamenting the surface of this Doric temple (most likely as metopes), the extant panels have preserved various imagery. On one plaque (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)), a male youth strides towards the right and carries a significant attribute under his right arm—the severed head of the Gorgon Medusa (her face is visible between the right hand and right hip of the striding figure). Not only is the painter successful here in relaying a particular story, but also the figure of Perseus shows great advancement from the previous century. The limbs are fleshy, the facial features are recognizable, and the hat and winged boots appropriately equip the hero for fast travel.

The Archaic Period (c. 600-480/479 BCE)

While Greek artisans continued to develop their individual crafts, storytelling ability, and more realistic portrayals of human figures throughout the Archaic Period, the city of Athens witnessed the rise and fall of tyrants and the introduction of democracy by the statesman Kleisthenes in the years 508 and 507 BCE.

Visually, the period is known for large-scale marble kouros (male youth) and kore (female youth) sculptures (see Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Showing the influence of ancient Egyptian sculpture (compare Menkaure and Queen from Ancient Egypt), the kouros stands rigidly with both arms extended at the side and one leg advanced. Frequently employed as grave markers, these sculptural types displayed unabashed nudity, highlighting their complicated hairstyles and abstracted musculature (see Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), left). The kore, on the other hand, was never nude. Not only was her form draped in layers of fabric, but she was also ornamented with jewelry and adorned with a crown. Though some have been discovered in funerary contexts, like Phrasiklea (see Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), right), a vast majority were found on the Acropolis in Athens. Ritualistically buried following desecration of this sanctuary by the Persians in 480 and 479 BCE, dozens of korai were unearthed alongside other dedicatory artifacts. While the identities of these figures have been hotly debated in recent times, most agree that they were originally intended as votive offerings to the goddess Athena.

The Classical Period (480/479-323 BCE)

Though experimentation in realistic movement began before the end of the Archaic Period, it was not until the Classical Period that two- and three-dimensional forms achieved proportions and postures that were naturalistic. The “Early Classical Period” (480/479-450 BCE, also known as the “Severe Style”) was a period of transition when some sculptural work displayed archaizing holdovers. As can be seen in the Kritios Boy, c. 480 BCE, the “Severe Style” features realistic anatomy, serious expressions, pouty lips, and thick eyelids. For painters, the development of perspective and multiple ground lines enriched compositions, as can be seen on the Niobid Painter’s vase in the Louvre (see Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)).

During the “High Classical Period” (450-400 BCE), there was great artistic success: from the innovative structures on the Acropolis to Polykleitos’ visual and cerebral manifestation of idealization in his sculpture of a young man holding a spear, the Doryphoros or “Canon” (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). Concurrently, however, Athens, Sparta, and their mutual allies were embroiled in the Peloponnesian War, a bitter conflict that lasted for several decades and ended in 404 BCE. Despite continued military activity throughout the “Late Classical Period” (400-323 BCE), artistic production and development continued apace. In addition to a new figural aesthetic in the fourth century known for its longer torsos and limbs, and smaller heads (for example, the Apoxyomenos), the first female nude was produced. Known as the Aphrodite of Knidos, c. 350 BCE, the sculpture pivots at the shoulders and hips into an S-Curve and stands with her right hand over her genitals in a pudica (or modest Venus) pose. Exhibited in a circular temple and visible from all sides, the Aphrodite of Knidos became one of the most celebrated sculptures in all of antiquity.

The Hellenistic Period and Beyond (323 BCE-31 BCE)

Following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, the Greeks and their influence stretched as far east as modern India. While some pieces intentionally mimicked the Classical style of the previous period such as Eutychides’ Tyche of Antioche (Louvre), other artists were more interested in capturing motion and emotion. For example, on the Great Altar of Zeus from Pergamon expressions of agony and a confused mass of limbs convey a newfound interest in drama (see Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)).

Architecturally, the scale of structures vastly increased, as can be seen with the Temple of Apollo at Didyma, and some complexes even terraced their surrounding landscape in order to create spectacular vistas as can be seem at the Sanctuary of Asklepios on Kos. Upon the defeat of Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt and, simultaneously, the Hellenistic Period came to a close. With the Roman admiration of and predilection for Greek art and culture, however, Classical aesthetics and teachings continued to endure from antiquity to the modern era.

Greek architectural orders

by Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker

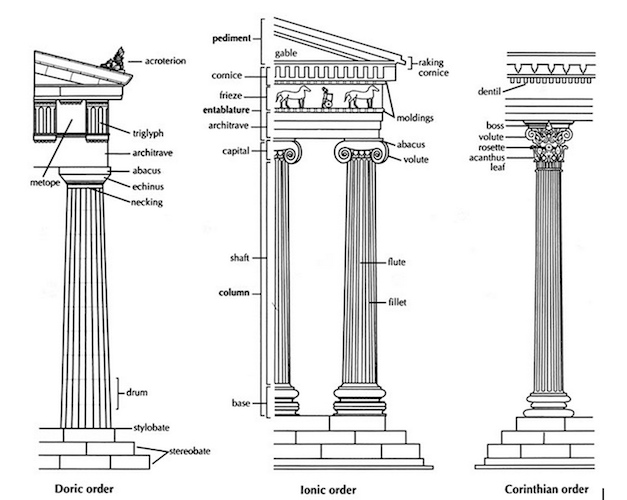

An architectural order describes a style of building. In classical architecture each order is readily identifiable by means of its proportions and profiles, as well as by various aesthetic details. The style of column employed serves as a useful index of the style itself, so identifying the order of the column will then, in turn, situate the order employed in the structure as a whole. The classical orders—described by the labels Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—do not merely serve as descriptors for the remains of ancient buildings, but as an index to the architectural and aesthetic development of Greek architecture itself.

The Doric order

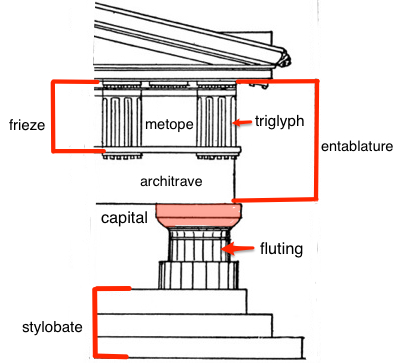

The Doric order is the earliest of the three Classical orders of architecture and represents an important moment in Mediterranean architecture when monumental construction made the transition from impermanent materials, such as wood, to permanent materials, namely stone. The Doric order is characterized by a plain, unadorned column capital and a column that rests directly on the stylobate of the temple without a base. The Doric entablature includes a frieze composed of trigylphs, or vertical plaques with three divisions, and metopes, square spaces for either painted or sculpted decoration (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). The columns are fluted and are of sturdy, if not stocky, proportions.

The Doric order emerged on the Greek mainland during the course of the late seventh century BCE and remained the predominant order for Greek temple construction through the early fifth century BCE, although notable buildings of the Classical period—especially the canonical Parthenon in Athens—still employ it. By 575 BCE the order may be properly identified, with some of the earliest surviving elements being the metope plaques from the Temple of Apollo at Thermon. Other early, but fragmentary, examples include the sanctuary of Hera at Argos, votive capitals from the island of Aegina, as well as early Doric capitals that were a part of the Temple of Athena Pronaia at Delphi in central Greece. The Doric order finds perhaps its fullest expression in the Parthenon (c. 447-432 BCE) at Athens designed by Iktinos and Kallikrates (see Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)).

The Ionic order

As its names suggests, the Ionic Order originated in Ionia, a coastal region of central Anatolia (today Turkey) where a number of ancient Greek settlements were located. Volutes (scroll-like ornaments) characterize the Ionic capital and a base supports the column, unlike the Doric order (see Figures \(\PageIndex{12}\) and \(\PageIndex{13}\)). The Ionic order developed in Ionia during the mid-sixth century BCE and had been transmitted to mainland Greece by the fifth century BCE. Among the earliest examples of the Ionic capital is the inscribed votive column from Naxos, dating to the end of the seventh century BCE.

The monumental temple dedicated to Hera on the island of Samos, built by the architect Rhoikos, c. 570-560 BCE, was the first of the great Ionic buildings, although it was destroyed by earthquake in short order. The sixth century BCE Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, a wonder of the ancient world, was also an Ionic design. In Athens the Ionic order influences some elements of the Parthenon (447-432 BCE), notably the Ionic frieze that encircles the cella of the temple. Ionic columns are also employed in the interior of the monumental gateway to the Acropolis known as the Propylaia (c. 437-432 BCE). The Ionic was promoted to an exterior order in the construction of the Erechtheion (c. 421-405 BCE) on the Athenian Acropolis (see Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)).The Ionic order is notable for its graceful proportions, giving a more slender and elegant profile than the Doric order. The ancient Roman architect Vitruvius compared the Doric module to a sturdy, male body, while the Ionic was possessed of more graceful, feminine proportions. The Ionic order incorporates a running frieze of continuous sculptural relief, as opposed to the Doric frieze composed of triglyphs and metopes.

The Corinthian order

The Corinthian order is both the latest and the most elaborate of the Classical orders of architecture. The order was employed in both Greek and Roman architecture, with minor variations, and gave rise, in turn, to the Composite order. As the name suggests, the origins of the order were connected in antiquity with the Greek city-state of Corinth where, according to the architectural writer Vitruvius, the sculptor Callimachus drew a set of acanthus leaves surrounding a votive basket (Vitr. 4.1.9-10). In archaeological terms the earliest known Corinthian capital comes from the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae and dates to c. 427 BCE.

The defining element of the Corinthian order is its elaborate, carved capital, which incorporates even more vegetal elements than the Ionic order does (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)). The stylized, carved leaves of an acanthus plant grow around the capital, generally terminating just below the abacus (see Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)). The Romans favored the Corinthian order, perhaps due to its slender properties. The order is employed in numerous notable Roman architectural monuments, including the Temple of Mars Ultor and the Pantheon in Rome, and the Maison Carrée in Nîmes.

Legacy of the Greek architectural canon

The canonical Greek architectural orders have exerted influence on architects and their imaginations for thousands of years. While Greek architecture played a key role in inspiring the Romans, its legacy also stretches far beyond antiquity. When James “Athenian” Stuart and Nicholas Revett visited Greece during the period from 1748 to 1755 and subsequently published The Antiquities of Athens and Other Monuments of Greece (1762) in London, the Neoclassical revolution was underway. Captivated by Stuart and Revett’s measured drawings and engravings, Europe suddenly demanded Greek forms. Architects the likes of Robert Adam drove the Neoclassical movement, creating buildings like Kedleston Hall, an English country house in Kedleston, Derbyshire. Neoclassicism even jumped the Atlantic Ocean to North America, spreading the rich heritage of Classical architecture even further—and making the Greek architectural orders not only extremely influential, but eternal.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Renee M. Gondek, "Introduction to ancient Greek art," in Smarthistory, August 14, 2016

- Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, "Greek architectural orders," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015