2.1: What is art history and where is it going?

- Page ID

- 108475

What is art history and where is it going?

by Dr. Robert Glass

Art history might seem like a relatively straightforward concept: “art” and “history” are subjects most of us first studied in elementary school. In practice, however, the idea of “the history of art” raises complex questions. What exactly do we mean by art, and what kind of history (or histories) should we explore? Let’s consider each term further.

Art versus artifact

The word “art” is derived from the Latin ars, which originally meant “skill” or “craft.” These meanings are still primary in other English words derived from ars, such as “artifact” (a thing made by human skill) and “artisan” (a person skilled at making things). The meanings of “art” and “artist,” however, are not so straightforward. We understand art as involving more than just skilled craftsmanship. What exactly distinguishes a work of art from an artifact, or an artist from an artisan?

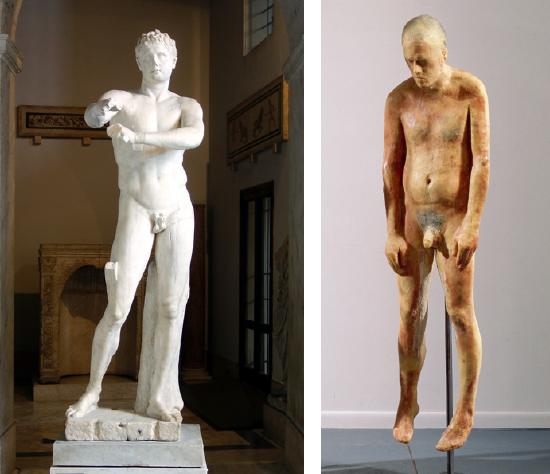

When asked this question, students typically come up with several ideas. One is beauty. Much art is visually striking, and in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, the analysis of aesthetic qualities was indeed central in art history. During this time, art that imitated ancient Greek and Roman art (the art of classical antiquity), was considered to embody a timeless perfection. Art historians focused on the so-called fine arts—painting, sculpture, and architecture—analyzing the virtues of their forms. Over the past century and a half, however, both art and art history have evolved radically.

History: Making Sense of the Past

Like definitions of art and beauty, ideas about history have changed over time. It might seem that writing history should be straightforward—it’s all based on facts, isn’t it? In theory, yes, but the evidence surviving from the past is vast, fragmentary, and messy. Historians must make decisions about what to include and exclude, how to organize the material, and what to say about it. In doing so, they create narratives that explain the past in ways that make sense in the present. Inevitably, as the present changes, these narratives are updated, rewritten, or discarded altogether and replaced with new ones. All history, then, is subjective—as much a product of the time and place it was written as of the evidence from the past that it interprets.

The discipline of art history developed in Europe during the colonial period (roughly the 15th to the mid-20th century), . Early art historians emphasized the European tradition, celebrating its Greek and Roman origins and the ideals of academic art. By the mid-20th century, a standard narrative for “Western art” was established that traced its development from the prehistoric, ancient, and medieval Mediterranean to modern Europe and the United States. Art from the rest of the world, labeled “non-Western art,” was typically treated only marginally and from a colonialist perspective.

The immense sociocultural changes that took place in the 20th century led art historians to amend these narratives. Accounts of Western art that once featured only white males were revised to include artists of color and women. The traditional focus on painting, sculpture, and architecture was expanded to include so-called minor arts such as ceramics and textiles and contemporary media such as video and performance art. Interest in non-Western art increased, accelerating dramatically in recent years.

Today, the biggest social development facing art history is globalism. As our world becomes increasingly interconnected, familiarity with different cultures and facility with diversity are essential. Art history, as the story of exceptional artifacts from a broad range of cultures, has a role to play in developing these skills. Now art historians ponder and debate how to reconcile the discipline’s European intellectual origins and its problematic colonialist legacy with contemporary multiculturalism and how to write art history in a global era.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Robert Glass, “What is art history and where is it going?,” in Smarthistory, October 28, 2017 (CC BY-NC-SA)