2.2: Art History and World Art History

- Page ID

- 126788

Art history and world art history

adapted from Smarthistory

“What’s visible becomes thinkable, and what’s thinkable becomes doable.” Timothy Snyder

In 2003, when Colin Powell went to the United Nations to make a case for going to war with Iraq, U.N. officials decided to discreetly cover the tapestry reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica that graces the entrance to the Secretariat. As Maureen Dowd observed in The New York Times, “Mr. Powell can’t very well seduce the world into bombing Iraq surrounded on camera by shrieking and mutilated women, men, children, bulls and horses.” The fact that it became necessary to hide Picasso’s anti-war masterpiece to make a case for militarism reminds us just how much power images and objects have in the world. As Timothy Snyder, a prominent historian of the Holocaust, argues in the quote above, images communicate ideas and influence people’s attitudes in consequential ways. This means that the work of art history—interpreting, contextualizing, and thinking critically about visual culture, and helping others to do so—really matters: not just for those involved directly with the art world, but for society at large.

A conservative discipline?

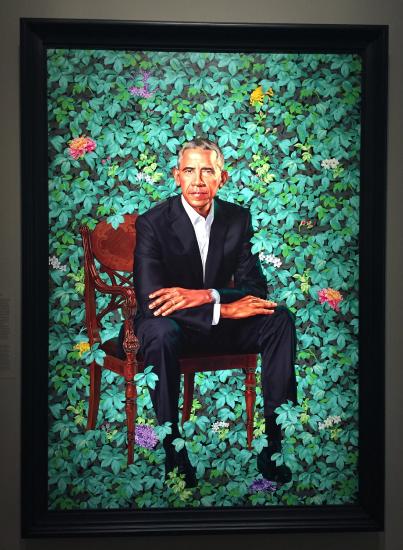

“Art history is relevant” is not how the discipline of art history is typically framed in popular discourse. Most people picture art historians as wealthy, white, intellectually conservative, and disconnected from the rest of the world. If the humanities are viewed by many critics as outdated fields with little to contribute to “productive,” STEM-driven society, art history has become their poster child—as President Obama (shown in the distinctly non-traditional presidential portrait in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) once unfortunately made clear.

This representation is frustrating. Many are drawn to art history not because of being narrow-minded, but because they deeply respect objects that they study, and want to make sure they're treated with the same meticulous rigor that other types of scholars afford texts. Although texts are vitally important for understanding history, images and objects also have immense communicative power, and they deserve equally meticulous and nuanced study. It is key to put the works first, giving close attention to the conditions of their makers, making, and use. This approach doesn’t stop with formal or iconographic analysis, though these are important foundations. Alongside profound respect for objects, their particular meanings, and their histories, critical theory is deeply influential. Feminist, post-structuralist, and postcolonial critiques of power, politics, and representation form the basis of much of this work. Art history is not inherently a conservative discipline, but instead is relevant, critical, and a product of its current moment—just like art itself.

Still, most introductory survey courses still lean heavily on what has been handed down to us through textbooks, departmental requirements, and the foundational art historical education of the instructors: the traditional Western canon (a list of the art that is most worthy of our attention and study). Even courses that include “global” in their titles, as many now do, required squeezing in absurdly pared-down units on "non-Western art" alongside the accepted narrative trajectory of the Western survey. Despite the “global” title, the real focus of this type of class remains clear. Heaven forbid we leave anything “important” out of the Western units! These classes, sadly, become surveys of “the West” with a smattering of “the rest.” [1]

The “global” in scholarly discourse

How must the discipline of art history change, what are the assumptions it must relinquish, and what ideas must it embrace in order to effect a true dislocation of “center-periphery” models of cultural intellectual exchange? Aruna D’Souza and Jill Casid

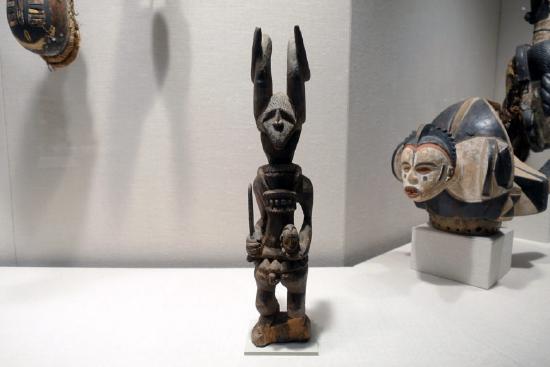

D’Souza and Casid’s words call attention to the continuing presence of the “center-periphery” model within our discipline: that is, Western art, with its more or less accepted trajectory through classical Greece and Rome, the European Renaissance, and modern Europe and Anglo North America, has historically been accorded a central place within the discipline, whereas art from everywhere else remains at the margins. The center-periphery model applies not only geographically, but also in terms of the people who create art: for instance, Native American and some Spanish colonial art are clearly part of the “periphery,” even though they are spatially embedded in North America. The marginalization of artists of color and women artists in all regions is also an important part of this larger problem. In addition to all this, art history itself arose as a discipline within a Western, colonial context, and this context was key in framing even such basic methodological concepts as what constitutes a work of art. A gracefully-formed and elegantly painted ceramic jar like the one in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) may be displayed as merely "craft" rather than capital-a Art.

Even when the center-periphery idea is used to critique the marginalization of non-European artworks and methods, the very structure of this model upholds the idea of Europe as a conceptual “center,” reifying the very power relationship it seeks to deconstruct. What do we do with these legacies? Is it enough to simply add more works from underrepresented cultures to the existing canon? Or do we attempt to do away with binary concepts like “center and periphery” altogether, complicating the notion of hermetic styles, schools, or traditions? Or, should we look to radically redefine how we define and analyze “art” itself and, consequently, its many histories?

A range of prominent scholars have been working to address these questions, though the results have not been as rapidly or widely influential as many would like. However tantalizing, erudite, and enjoyable as some of these offerings may be, they almost all seem to lack a key aspect: broad, seamless employability at the basic level of the art history classroom.

The “global” problem in the classroom

Most of the globe remains at the periphery of undergraduate art history education, as recent studies have shown. This overwhelmingly Western bias does not end solely with departmental requirements; it also exists at the basic level of the introductory art history survey curriculum. The most widely-used textbooks still organize the history of art in terms of the well-developed Western canon, with other art traditions presented as holistic, geographically based addenda that reduce the span of entire continents and multiple centuries to single chapters.

Reframing the world

In 1987, the artist Alfredo Jaar provoked furor with his public artwork A Logo for America, an animation he designed for Times Square’s Spectacolor board wherein he proclaimed that the United States is not “America.” Rather, the animation posited, the term applies to places all across the Americas—both North and South. Jaar’s snappy, 15-second jab at the narcissism and cultural hegemony of the United States reminds us of the immense power that even the most seemingly simple words or concepts can have in framing global identities and power relations. Works like this push us to question the basic ways of thinking about the world that we often assume, in light of the inequitable systemic conditions that produced them, are neutral. This process of self-reflexively examining—and working to deconstruct—those conditions is commonly referred to as the work of discursive “decolonization.”

Jaar’s emphasis on terminology reminds us that, as we consider how to decolonize the canon in terms of the artworks we include, we also have to think carefully about the analytical tools we use to interpret and contextualize them. Our methods, formulated within a primarily Western context (both in terms of the works of art they were applied to and those who applied them), come with their own inherent biases.

A canon can be defined as a rule for a standard of beauty developed for artists to follow, and as a body of works considered especially important. In art history, the “Western” canon of artworks often accorded highest status and most celebrated was formulated by white Euro/American men—and consisted of art by predominantly white, Euro/American, cisgender, men. Artistic canons, however, are not static and have been changing and expanding over time. As Dr. Mary Kelly and Dr. Ceren Özpınar argue, "The conventional 'centering' of art history in Europe and America and traditional 'Western' methodologies is increasingly unsatisfactory in the current age. Therefore, further emphasis on translocal and transnational encounters are necessary in order to tease out conditions of global exchange."

Today, many scholars are thinking about how to do that work and “decolonize” canons in various disciplines, including art history. This involves an active reconsideration and reordering of an important body of works, by first labeling colonialist or settler influences and artistic cultural legacies, and then actively resisting or recasting the canon with a different set of values, artists, and influences.

For further discussion into decolonizing art history and the canon, including how that might look for educators, please explore the following resources:

- Catherine Grant and Dorothy Price's "Decolonizing Art History" features interviews with art historians about the state of the field and efforts these professionals are making towards decolonization. Professors such as James D'Emilio explore the topic, arguing: "A decolonized art history looks beyond diversifying canons, curricula, and practitioners. It recognizes that we now study, teach, and display art with culturally specific methods whose universal claims reflect early modern and modern European hegemony."

- On The New York Times' "Still Processing" podcast, Wesley Morris and Daphne A. Brooks explore the strict and problematic confines of artistic canons in their episode "We're Never Going to Get that Top 40 Out of Us."

- Amber Hickey and Ana Tuazon provide a case study for decolonizing the classroom in "Decolonizing and Diversifying Are Two Different Things: A Workshop Case Study" and a zine with Decolonial Strategies for the Art History Classroom.

“Global” vs. “world”

This critique of methods is at the root of key current discussions about the use of the word “global” itself. John Onians has proposed the term “world art studies” (as opposed to “global art history”) to differentiate between research that looks at the “global”—i.e. globalized, networked—contemporary world through a traditional art historical lens, and that which looks at the “world,” looking at the longer span of historical time and geographic space, using a variety of interdisciplinary methods. The notion of “world” art studies has become an important point of discussion within subfields such as colonial Latin American art, precisely because it entails an interdisciplinary approach that helps to cut through inherited disciplinary boundaries around artists, styles, and periods.

Questioning, critiquing, and connecting

As Benjamin Harris, a specialist on the global contemporary art world, reminds us: “A truly ‘global field of art history’ would comprise an intellectual intervention premised on a critique of Western power in the world as it exists and is reproduced (and challenged) in cultural and artistic terms.” I believe many art historians would agree with this statement, but putting it into practice—especially in the Western survey, with its well-established narratives about stylistic lineage, single heroic artists as innovators, and geographical and chronological divisions—is challenging.

Whether or not it is important for students to take the Western survey at some point in their art history education, it is clear that students need a robust and current toolkit for looking at and analyzing art. It is also important to decenter the canon by looking at art through non-traditional lenses. Indigenous scholars, in particular, have been active in exploring alternative ways of analyzing and teaching about art. An example of this comes from Carmen Robertson, faculty in the Department of Indian Fine Arts at the First Nations University of Canada. As she states in an interview:

The first and most profound difference I find in teaching my courses is the decentering that takes place. European art is not the filter through which these courses are taught. Aboriginal values and traditions inform and direct discussions of the artwork shown in class. I embrace . . . an interdisciplinary approach [which includes] . . . connections to traditional ways, colonial adaptations and recent developments[.]

For instance, when looking at West African Igbo art, Robertson has her students read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and then “discuss both traditional and contemporary expressions by Igbo artists, how museums display their work, and the effects of colonization on the arts.”

Networks as critique

What these approaches have in common, besides their willingness to expand the lens of art history to include concerns such as institutional, political, and cultural power relations, is a focus on objects as interconnected. Scholars in Global Renaissance studies, for instance, have been pioneering ways of reframing the art production of the trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific in order to question the traditional periodization and categories of style that arose in the art history of the European Renaissance. Art historian Ananda Cohen-Aponte points to the existence and necessary acknowledgement of “many Renaissances and many Baroques whose artistic fruits spilled into territories across the Americas and Asia.” [2]

The reframing of objects within global networks can itself give rise to a form of critique, since, if we look closely and rigorously, these relationships demand new, more interdisciplinary approaches in order to be fully understood. But Cohen-Aponte brings up another important point as well: if we want to truly decolonize the discourse of art history, then, we also have an obligation to make space for Indigenous scholars and scholars from the Global South to take the lead writing the history of art.

Notes:

[1] Art history’s awareness of these problems is nothing new. To name just three key (dare I say canonical?) texts: John Berger tackled these issues in his seminal 1972 series and book, Ways of Seeing; Edward Said’s 1978 Orientalism has become its own shorthand; and Hans Belting’s many writings on globalization in the art world are a touchstone for anyone who studies contemporary art.

[2] Ananda Cohen-Aponte, "Decolonizing the Global Renaissance: A View from the Andes," in The Globalization of Renaissance Art: A Critical Review, edited by Daniel Savoy (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 73–74.

Articles in this section:

Smarthistory, "Art history and world art history," in Smarthistory, January 12, 2021 (CC BY-NC-SA)