2.22: Post-Impressionism

- Page ID

- 143509

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Post-Impressionism

Post-Impression refers to a genre that rejected the naturalism of Impressionism in favor of using color and form in more expressive manners.

Key Points

- Post-Impressionists extended the use of vivid colors, thick application of paint, distinctive brush strokes, and real-life subject matter, and were more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, distort forms for expressive effect, and to use unnatural or arbitrary colors in their compositions.

- Although they were often exhibited together, Post-Impressionist artists were not in agreement concerning a cohesive movement, and younger painters in the early 20th century worked in geographically disparate regions and in various stylistic categories, such as Fauvism and Cubism.

- The term ” Post- Impressionism ” was coined by the British artist and art critic Roger Fry in 1910, to describe the development of French art since Manet and the Impressionists.

Key Terms

- Post-Impressionism: (Art) a genre of painting that rejected the naturalism of impressionism, using color and form in more expressive manners.

- Post-Impressionist: French art or artists belonging to a genre after Manet, which extended the style of Impressionism while rejecting its limitations; they continued using vivid colors, thick application of paint, distinctive brush strokes, and real-life subject matter, but they were more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, to distort form for expressive effect, and to use unnatural or arbitrary color.

- post-and-lintel: A simple construction method using a header or architrave as the horizontal member over a building void (lintel) supported at its ends by two vertical columns or pillars (posts).

Move from Naturalism

Post-Impression refers to a genre of painting that rejected the naturalism of Impressionism, in favor of using color and form in more expressive manners. The term “Post-Impressionism” was coined by the British artist and art critic Roger Fry in 1910 to describe the development of French art since Manet. Post-Impressionists extended Impressionism while rejecting its limitations. For example, they continued using vivid colors, thick application of paint, distinctive brush strokes, and real-life subject matter, but they were also more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, distort forms for expressive effect, and to use unnatural or arbitrary colors in their compositions.

Significant Artists of Post-Impressionism

Post-Impressionism developed from Impressionism. From the 1880s onward, several artists, including Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, envisioned different precepts for the use of color, pattern, form, and line, deriving these new directions from the Impressionist example. These artists were slightly younger than the Impressionists, and their work contemporaneously became known as Post-Impressionism. Some of the original Impressionist artists also ventured into this new territory. Camille Pissarro briefly painted in a pointillist manner, and even Monet abandoned strict enpleinair painting. Paul Cézanne, who participated in the first and third Impressionist exhibitions, developed a highly individual vision emphasizing pictorial structure; he is most often called a post-Impressionist. Although these cases illustrate the difficulty of assigning labels, the work of the original Impressionist painters may, by definition, be categorized as Impressionism.

A Diverse Search for Direction

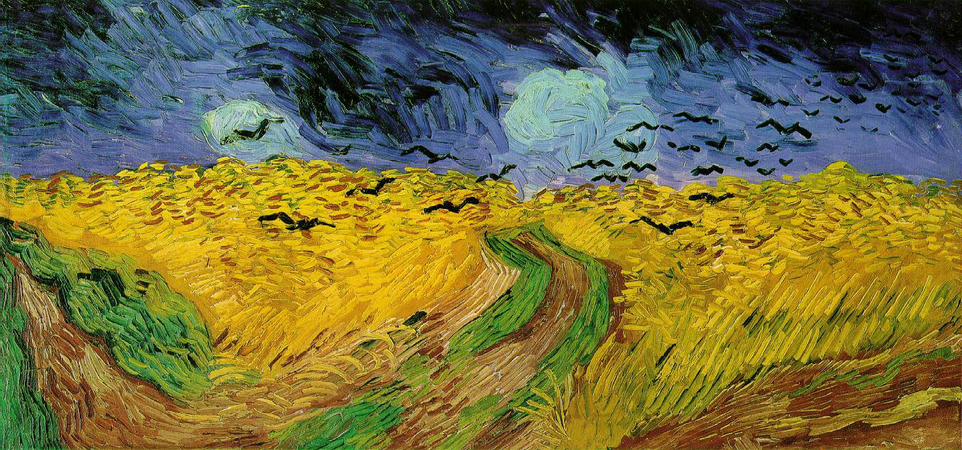

The Post-Impressionists were dissatisfied with the triviality of subject matter and the loss of structure in Impressionist paintings, although they did not agree on the way forward. Georges Seurat and his followers, for instance, concerned themselves with Pointillism, the systematic use of tiny dots of color based on various new theories of optics. Paul Cézanne set out to restore a sense of order and structure to painting by reducing objects to their basic shapes while retaining the bright fresh colors of Impressionism. Vincent van Gogh used vibrant colors and active brush strokes to convey his feelings in the face of nature and his state of mind. Hence, although they were often exhibited together, PostImpressionist artists were not in agreement concerning a cohesive movement, and younger painters in the early 20th century worked in geographically disparate regions and in various stylistic categories.

Cézanne

Cézanne was a French, Post-Impressionist painter whose work highlights the transition from the 19th century to the early 20th century.

Key Points

- Cézanne’s early work is often concerned with the figure in the landscape, often depicting groups of large, heavy figures. In Cézanne’s mature work there is a solidified, almost architectural style of painting. To this end, he structurally ordered his perceptions into simple forms (techtonic “passages” of color) and color planes.

- This exploration rendered slightly different, yet simultaneous, visual perceptions of the same phenomena to provide the viewer with a different aesthetic experience.

- Cezanne ‘s “Dark Period” from 1861–1870 contains works that are characterized by dark colors and the heavy use of black.

- The lightness of his Impressionist works contrast sharply with the dramatic resignation found in his final period of productivity from 1898–1905. This resignation informs several still life paintings that depict skulls as their subject.

Key Terms

- Cezanne: Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) was a French artist and Post-Impressionist painter whose work laid the foundations of the transition from the 19th century conception of artistic endeavour to a new and radically different world of art in the 20th century.

- Impressionism: A 19th-century art movement that originated with a group of Paris-based artists. Impressionist painting characteristics include relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), common, ordinary subject matter, inclusion of movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience, and unusual visual angles.

- Post-Impressionism: (Art) a genre of painting that rejected the naturalism of impressionism, using color and form in more expressive manners.

Introduction

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) was a French artist and Post- Impressionism painter whose work began the transition from the 19th century conception of artistic endeavor to a new and radically different world of art. Cézanne’s often repetitive brushstrokes (“passages”)are highly characteristic and clearly recognizable. He used planes of color and small brushstrokes to form complex fields and convey intense study of his subjects.

Early Work

Cézanne’s early work is often concerned with the figure in the landscape, often depicting groups of large, heavy figures. Later, he became more interested in working from direct observation, gradually developing a light, airy painting style. Nevertheless, in Cézanne’s mature work, there is development of a solidified, almost architectural style of painting. To this end, he structurally ordered whatever he perceived into simple forms and color planes.

Cézanne was interested in the simplification of naturally occurring forms to their geometric essentials, wanting to “treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone.” For example, a tree trunk may be conceived of as a cylinder and an apple or orange as a sphere. Additionally, his desire to capture the truth of perception led him to explore binocular graphic vision. This exploration rendered slightly different, yet simultaneous, visual perceptions of the same phenomena, providing the viewer with a different aesthetic experience of depth.

After the start of the Franco-Prussian War in July 1870, Cézanne’s canvases grew much brighter and more reflective of Impressionism. Cézanne moved between Paris and Provence, exhibiting in the first (1874) and third Impressionist shows (1877). In 1875, he attracted the attention of collector Victor Chocquet, whose commissions provided some financial relief. On the whole, however, Cézanne’s exhibited paintings attracted hilarity, outrage, and sarcasm.

The lightness of his Impressionist works contrast sharply with his dramatic resignation in his final period of productivity from 1898–1905. This resignation informs several still life paintings that depict skulls as their subject.

Cézanne’s explorations of geometric simplification and optical phenomena inspired Picasso, Braque, Gris, and others to experiment with ever more complex multiple views of the same subject. Cézanne thus sparked one of the most revolutionary areas of artistic enquiry of the 20th century, one which was to affect the development of modern art. A prize for special achievement in the arts was created in his memory. The “Cézanne medal” is granted by the French city of Aix en Provence, his home town.

He painted Mont Sainte-Victoire near his home more than 60 times. The passages of paint he used to create the various planes that suggest structures and foliage can be seen in the image below. These passages are characterized by a single color – say, ocher – applied to an area in four or five brushstrokes going in the same direction. Another color – possibly a grey – is applied in brushstrokes going in another direction. Together they suggest the planes of a house or rock without painting either the contours of that object or its local color.

Van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh initially intended to be a preacher in his native Holland. He especially wanted to minister to the poverty-stricken peasants and miners for whom he had a deep sympathy. Sadly, he was never able to connect with people for long but his spiritual feelings eventually found an outlet in his paintings and drawings, done largely in isolation during his lifetime. His early work from the 1880s evinced thick brushstrokes of darkly pigmented earth tones. Van Gogh did go to Paris where his brother, Theo, was an art dealer. There he became familiar with both the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists (or Post-Impressionists) like Signac. He found in the work of Gauguin what he thought was a kindred spirit and left Paris for the south of France in Arles hoping to found an artists’ collective with Gauguin and Emile Bernard as members. After an abortive visit from Gauguin this idea had to be abandoned.

In Arles, van Gogh’s style became pronounced with brilliant color and an energetic surface with active brushstrokes of paint. Some of his most characteristic works, like Starry Night, seem to suggest a kind of spirit – or animism – moving through nature.

Starry Night – Google Art Project.jpg, created: 1889date QS:P571,+1889-00-00T00:00:00Z/9

Gauguin

Paul Gauguin is associated with the Post Impressionists. He came to painting late after a career as a stockbroker leaving a family to search for a more “primitive” and perfect style of life. After finding first Arles with van Gogh and then Brittany in France still too civilized, Gauguin decamped to Tahiti where he painted the indigenous people. Influenced in his style by both Pissarro and Paul Cézanne, Gauguin used color and distorted form and perspective to evoke what he felt was an essential or spiritual truth in his subjects. He died during his second trip to Tahiti having never achieved much recognition or financial success in France.

Seurat

Georges Seurat was a Parisian from a wealthy landowning family. He studied art at a school of design and sculpture near the family home before enrolling at the École des Beaux-Arts which he left in 1879 for military service. He returned to Paris and took an apartment with his friend from the army, another artist, Aman-Jean.

Seurat was a modernist; he turned to the subject matter of the Impressionists, the café-concerts, circuses, and images of the classes mixing in moments of leisure in the landscape. His style was his own. Drawn to contemporary theories about color, optics, and perception, Seurat knew of the scientist-writers Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood. Chevreul came to his color theories after having served as the director of the Gobelins Manufactory in Paris. There he became aware of the different perceptions about color depending on the colors surrounding it – he called this concept simultaneous contrast. His “chromatic diagram” of 1855 is an early color wheel with complementary colors and other color relatio ships. Chevreul was also a chemist, an inventor of an early form of soap, and a gerontologist who himself lived to be 102.

Seurat developed his reading on color theory into his own method called “pointillism”. He laid down color in small brushstrokes – dots – next to each other and overlapping. In this way he thought to create the light and shadow other painters got from pre-mixing color on a palette and placing it down in a solid brushstroke or area of paint. For Seurat this wasn’t strictly about color or science – he believed that this approach created harmony and emotion in a painting. He looked for emotional effects through color –warm or cool – and directional line.

In addition to the paintings Seurat was a prolific drawer. To bring his pointillist technique into the dry medium he used a soft waxy crayon called a Conté crayon after the French military man who had invented it – on a paper with a rough “toothy” surface. He could modulate the pressure of the crayon to create basically a dot-screened effect on the paper.

Seurat died at the very early age of 31, but he left behind a body of work that is unique and has inspired other artists and even a Broadway musical – Sunday in the Park with Georges by Steven Sondheim. His work is sometimes called “NeoImpressionism” instead of Post-Impressionism, but for our purposes it belongs in this category.