5.4: Cinematographic Art

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174438

Introduction

Video art exploits audio and visual technology using multiple formats of recorders, computers, video tapes, television sets, projectors, and newer digital equipment. Video art began in the 1960s with the advent of the old analog video recorders and tapes. Nam June Paik was considered the pioneer of the concept when in 1965, he made a recording and played it in a local café. Previously, only 8 and 16mm film were available, and it had to be played on expensive, cumbersome equipment. Paik used new technology from SONY to easily record and play videos, the first step for ordinary consumers to afford video-recording technology. The inexpensive technology gave artists an experimental platform, challenging them. In the 1970s, artists and technicians combined elements like multiple television sets to display video images. Many artists used the camera to create and project personal or taboo images and videos onto displays, challenging the ideas of what was acceptable and shattering traditional art concepts. When confronted with this new technology outside the conventional description of art, museums were horrified at the concept of sounds, movement, unknown objects sitting in their white-walled spaces.

Technological abilities increased exponentially during the 1980s and 1990s; hardware became more sophisticated and smaller as software added more capabilities. Artists found it easier to create video installations with unknown innovations. Artists used the newer capabilities to develop installations, virtual reality, or performance art. Video art also allowed artists to express social concepts and political causes in methods common to how people received information. Social movements became dependent on video technology to define and expand their messages. The video capabilities allowed artists to mimic more traditional art forms, utilizing video signals' distortion and dissonance as the creative platform. By the 1990s, the museums finally accepted the new forms of artwork as the advance of technology propelled the art form into the mainstream. Video obtained the rank of the other art mediums, art schools offering video as a viable specialization.

Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik (1932-2006) was born in Seoul, Korea; his father owned a large textile company. He was the youngest of five children and trained as a pianist as a child. During the Korean war, the family fled to Hong Kong and then Japan, where, in 1956, he received a BA from the University of Tokyo in aesthetics. Paik went to West Germany to further study music and became part of a new experimental art group. When he moved to the United States in the early 1960s, Paik started to experiment with synthesizers and how to manipulate musical sounds. He first used a Sony recorder until 1967 when Sony introduced a new portable video-tape-recorder giving Paik the platform he needed, creating a new direction in art. Paik's first exhibition was based on thirteen television sets. He continued to use TV sets for experiments, spanning the capabilities of technology and art. By 1974, he proposed the electronic information superhighway, connecting cities and people with satellites, coaxial cables, and fiber optics. Paik wanted to distribute videos freely, flowing through the information highway. His optimism and forward-thinking forecasted the future and is internationally considered the Father of Video Art. Paik also began to make installations from old televisions sets and video monitors to display different images on closed circuits across the installation. He used televisions sets to make robots adding wire, metal, and miscellaneous parts. Paik understood the future capabilities of imagery and used file and video as multi textual art forms.

"Using television, as well as the modalities of single-channel videotape and sculptural/installation formats, he imbued the electronic moving image with new meanings…transforming the electronic moving image into an artist's medium, part of the history of the media art."[1]

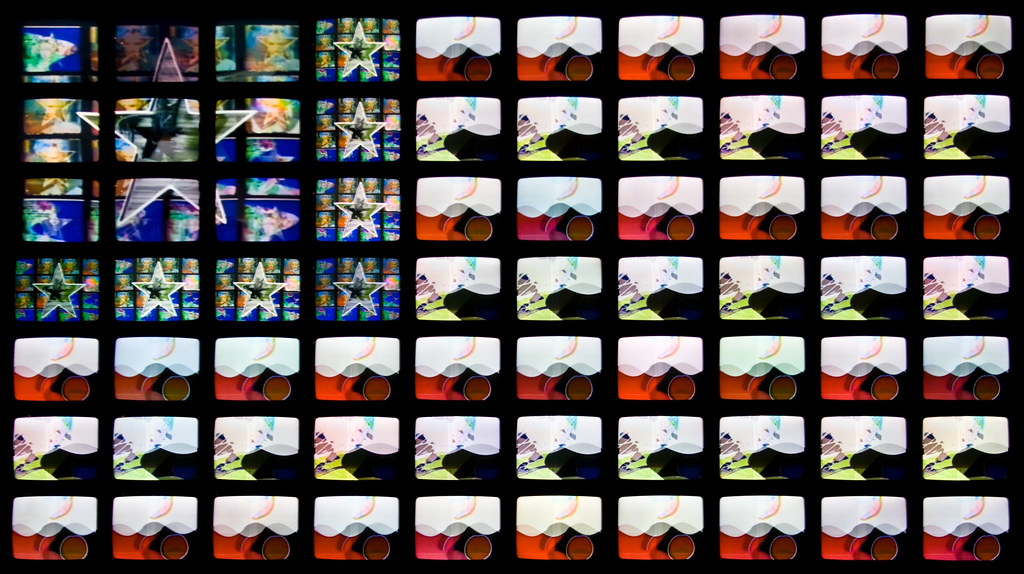

Paik used television sets to create the American flag; in this installation, Video Flag (7.4.1), seventy sets are primarily programmed to red, white, and blue images. He used magnets to manipulate the signals and synthesizers, video feedback, and various technologies to create different colors and shapes. Paik made several other installations of flags in a variety of sizes. In this flag, he projected on a continuous loop, 24 hours a day, different images of political images. Technology has a finite ability to continue working, and all of Paik's flag installations have been undergoing conservation efforts, using new technology and wiring to preserve the mechanisms.

In 1964, when Paik first came to America, the interstate highway system, established under Eisenhower's presidency, was only nine years old. The highway ran from coast to coast, linking the states of the country. At the time, detailed maps guided the drivers from state to state. Restaurants and motels were constructed across the country, their neon nights burning brightly, different states presenting different cultures. The entire country also embraced the use of the television set, linking the news and days events with the homes of America. Paik recognized how to use video media to connect people and how it would transform everyone's life. He created Electronic Superhighway (7.4.2), a massive installation of 336 television sets, 50 DVD players, 3,750 feet of cable, and 575 feet of multicolored neon tubing. [2] On the different monitors, he plays images to represent each state surrounded by flashing tubes of neon light. Paik wanted to display his vision of how technology and communication would advance in the future.

Megatron Matrix (7.4.3) was an installation of 215 monitors. Paik played different clips in sections, some based on his images from his home country of South Korea and others different ideas of entertainment and culture of the United States. All of Paik's installations were prophetic of the world's future information age.

Alan Rath

From Cincinnati, Ohio, Alan Rath (1959-2020) graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with his degree in electrical engineering. Rath was always captivated by machinery when he was young. He worked for a short while as an engineer before moving to California to study visual arts, incorporating his knowledge of machinery and sculptures. Rath created his electronics and wrote the software to run his sculptures, even changing the presentations of the sculptures over the years. Most of his works featured computer-generated independent body parts; a moving eye or a twitching nose. Rath wanted to reflect the correlation between technological systems and humanity. He primarily featured eyes in many of his works, sometimes staring at viewers, blinking, or jumping around the screen. Rath made sculptures somewhat alien, using fiberglass, polypropylene, aluminum, custom electronics, and partridge feathers because of their fluidity.[3] Rath used motion sensors and heat detectors, the viewers themselves causing motion.

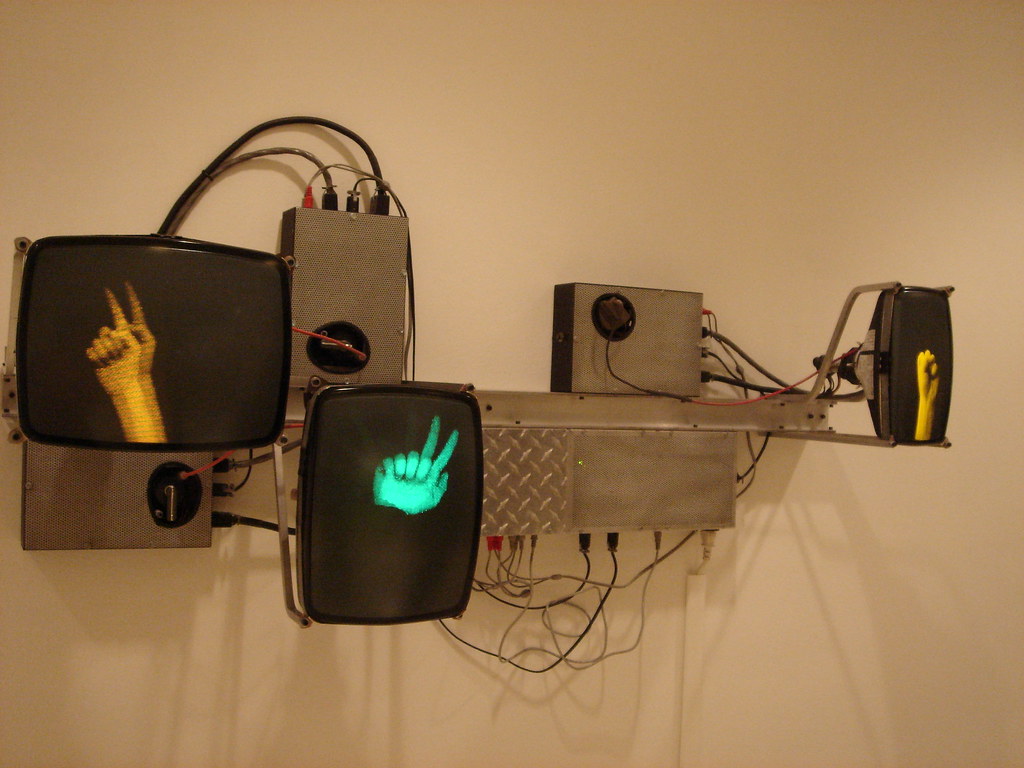

Clock II (7.4.4) was one of his early creations. At this time, the industry was in transition, moving from electrical to computational. Rath's work used cathode ray tubes (CRT), the precursor to current liquid crystal displays (LCD). In this installation, he has two screens, each with a hand, the extended fingers moving. The sculpture needed large boxes with multiple large cables to make the images move. Throughout his career, Rath added different sculptures of his Eyeris series.

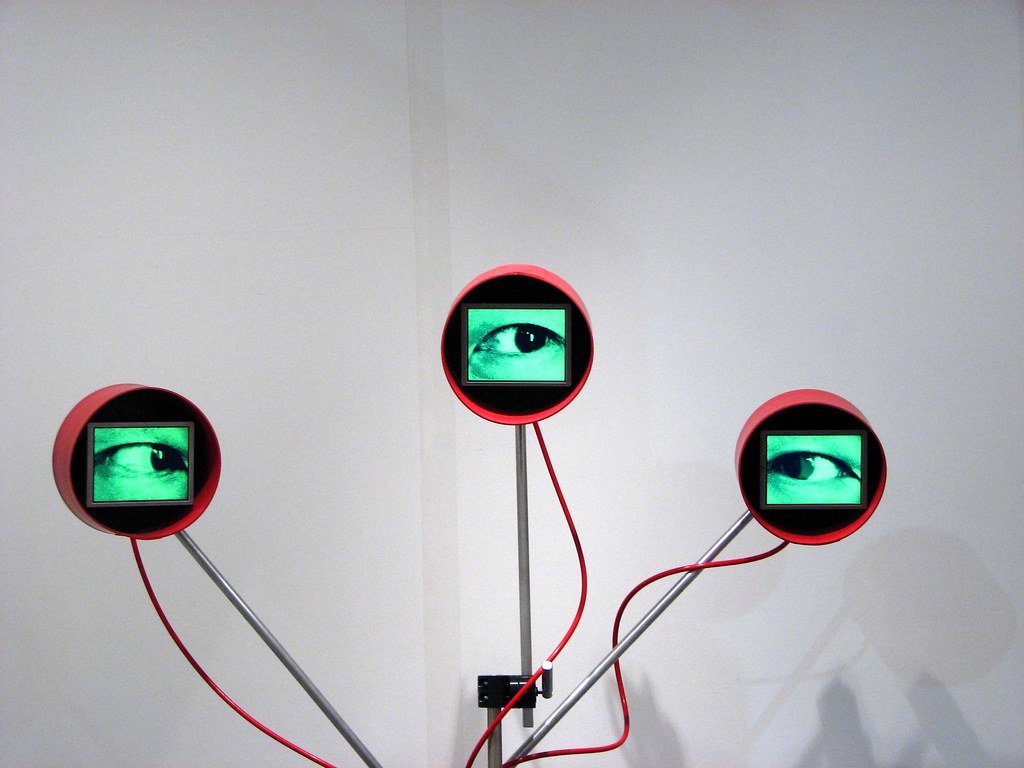

In Eyeris V (7.4.5), as in the others, the eyes follow the viewer's movement, projecting an eerie feeling. The loose red power cords and straight aluminum rods give the structures a skeleton-like look.

Instead of eyes, Atherton Wallflower (7.4.6) used audio speakers of different sizes, almost appearing like flowers blooming from the wall. The thick, looped cords plugged into the box on the floor, anchoring and bringing the elements together. Although a viewer did not hear any noise from the speakers, each speaker pulsates, demonstrating the invisible sound.

Positively (7.4.7), Absolutely, and Again was a series of moving sculptures featuring feathers. Positively, with its plumes of bright pink ostrich feathers move whenever it senses motion. The feathers on long robotic arms move open and closed, dancing as though welcoming the viewer into its embrace. The whirring of the motors adds sound to enhance the captivating feeling.

Joan Jonas

Joan Jonas (1936-) was born in New York City. Her family focused on multiple types of arts, including taking her to museums, operas, and the theater. Jonas always said she wanted to be an artist, believing it took her a long time to achieve success because she was a woman. Jonas graduated from Mount Holyoke College with a degree in Art History and followed this with an MFA from Columbia University in sculpture. In the New York art scene, Jonas worked with choreographers in the theaters and, by 1968, started working with mixed props and symbolic works, frequently using mirrors. By the early 1970s, the new video concepts started, and Jonas started experimenting with making different short videos. She incorporated images of herself in the live video shots, the first artist to do that and perhaps the forerunner of the selfie. Jonas' central motifs covered choreography, nature, or rituals, all enhanced with mirrors. She made her own scripts retelling myths and tales into visual landscapes. Jonas could mix performance art with her video art through dance, music, costumes, and video technology.

For her video, Light Time Tales (7.4.8) was a video installation compiled from ten different installations she made on ten single-channel videos. Jonas used an old, empty factory site over 5,500 square meters. First, Jonas removed all the walls and constructed the exhibition through a long snaking pathway for viewers to follow. Every video piece had its own space and sound. However, each one was visible from multiple points, and the individual sounds from each video resonated through the building. Reading Dante were performance videos Jonas created based on Dante's Divine Comedy. She initially made a short video with different gestural drawings and percussion noises.

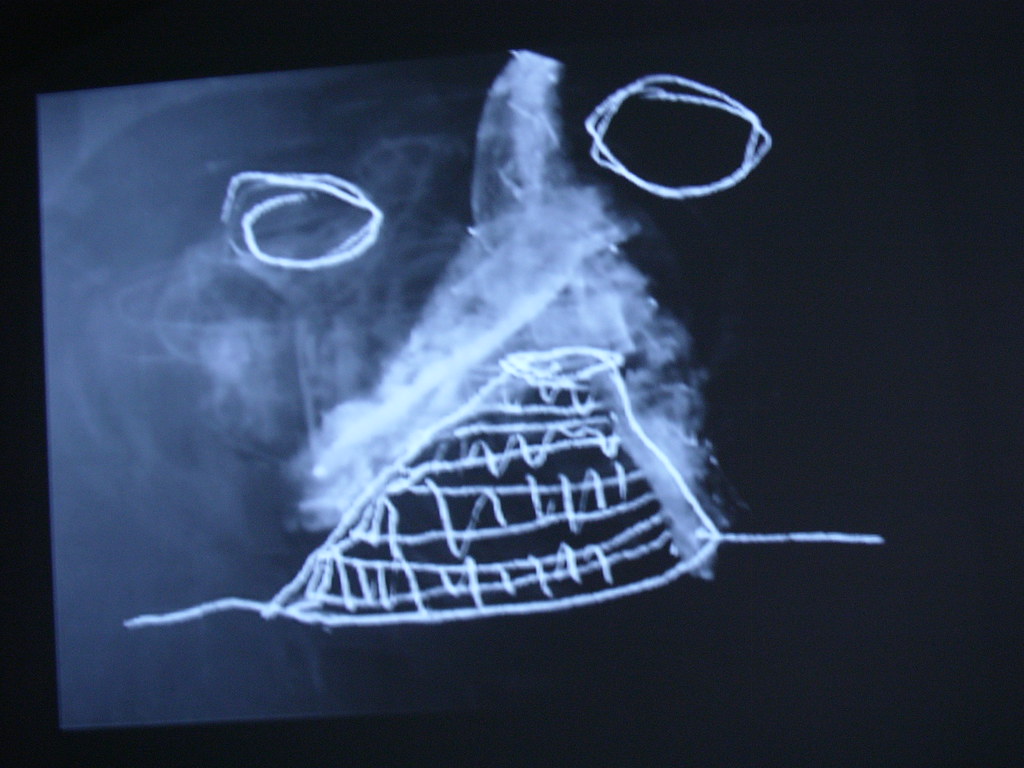

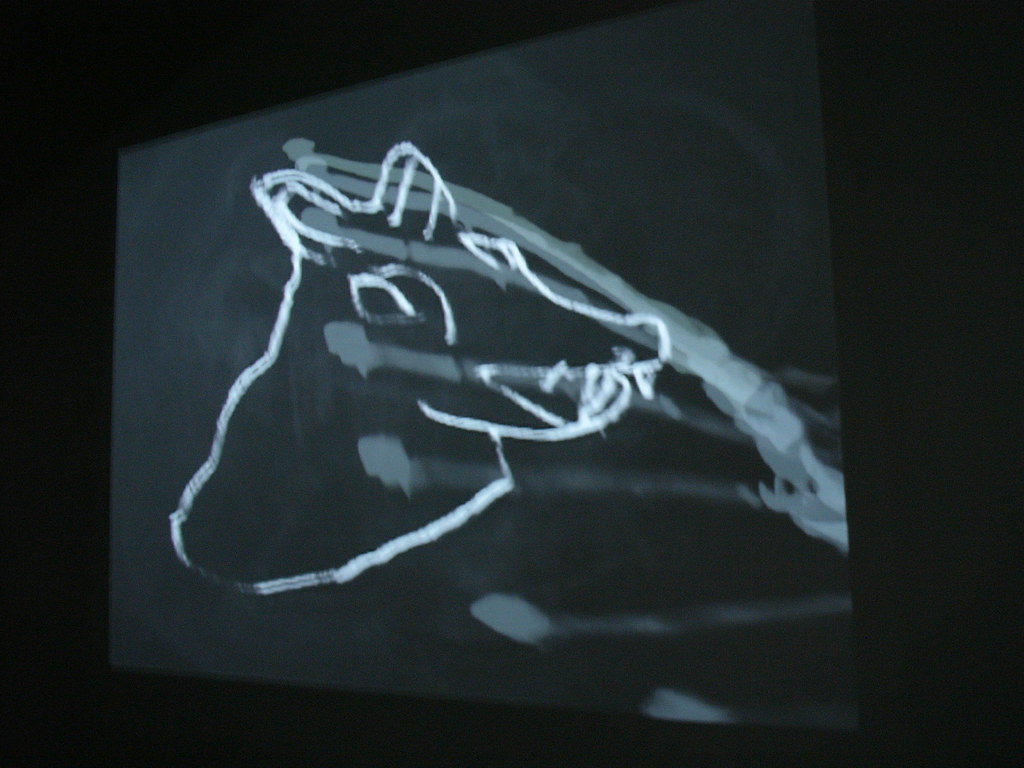

In 1994, Jonas expanded the concept and made a series of videos, all incorporated into an installation running over distinctive video projections. For the videos, she integrated chalk drawings (7.4.9, 7.4.10), masks, photographs, and other miscellaneous objects; some of the elements were drawn, others acted, all imagined into Jonas' exceptional work.

Pipilotti Rist

Pipilotti Rist (1962-) is from Switzerland. She changed her name from Elisabeth to Pipilotti because her nickname was Lotti. At the beginning of college, she majored in theoretical physics for a short period before switching to art, illustration, and video at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. Afterward, Rist joined a performance group and made her prize-winning video. She began making short videos and experimented by altering color, speed, or sound with themes generally based on gender or sexuality. She added music to the simplistic videos generating pleasure and happiness. Rist was considered a feminist in her work; however, she believed the images of women stood for all humans. Rist used vibrant colors, unique musical scores, and sweeping vistas with the undertow of sexuality in her expanded, large-scale installations. In her first few videos, she experimented with nude images, becoming part of the allure of her work.

Pixel Forest (7.4.11) was a massive installation with multiple screens and changing projections. The different images and short videos incorporate elements across her career. Rist frequently integrates herself in the videos, whether older, fragmented nude images or her distorted face pressed against the glass. She often blurred the lines between the interaction of bodies, how the camera is used, and portrayal on the screens. The viewer walked through the videos in different rooms as the cameras projected onto translucent screens; the shadows of the viewer's body became part of the visuals.

Parasimpatico (7.4.12) was a compilation of older works mixed with newer short videos creating floating images with psychedelic colors and otherworldly sensations. Rist placed objects in unexpected containers, toilets, purses, or bottles and projected them onto suggestive surfaces. She wanted to explore all senses in enveloping experiences. Rist also incorporated humor in the video installation and the environment around the installation, including the staircases and auditorium.

The Massachusetts Chandelier (7.4.13) was made of clean, used underpants hung on a frame of tiered metal. Some of the underpants had lace, others with pockets, most were larger sizes, a mixture of varieties for men and women. Rist used a 2-channel video running color without her usual music.

Christian Marclay

Although Christian Marclay (1955-) was born in California, he holds American and Swiss citizenship, his father from Switzerland. He lived most of his childhood in Switzerland and studied art in Geneva before receiving a BFA from Massachusetts College of Art. Initially, Marclay was attracted to music, creating songs and collecting tapes. He purchased records at thrift stores trying to re-assemble the music on the records with different noises. Marclay also played in live performances and made a few recordings. He gradually became interested in visual art to represent his sounds, combining video and sound. Marclay disassembled and reorganized the sounds together, joining different LP records and collages made from recombined sounds.

2822 Records (PS1) (7.4.14) was composed of vinyl records installed on the floor. Marclay used 12-inch LP records from every genre of music, demonstrating the wide variety of sounds in music. Marclay said, "I wanted to disrupt people's usual relation to this fragile object, be destructive and make you aware that every step you take will transform this music into noise. Music is about life, and you can't freeze life because it is as fragile as these records."[4] Marclay also made some installations by throwing records over the floor, unattached. The loose records made it difficult to walk on, the viewer more carefully moving, gaining more attachment to the individual recordings. Marclay thought of records as his tools, providing the ability to recreate, change and destroy the original recording. He thought of the vinyl record as an art form itself. In the installation, the useless records reclaimed their visual possibilities.

In Gestures (7.4.15), Marclay created an extensive video installation based on his accumulation of vintage record turntables, old musical instruments, and LP records. He built a multisensory experience with images combined with sound. The visuals include pictures and actions to recreate music with the record on the turntable and the sounds produced.

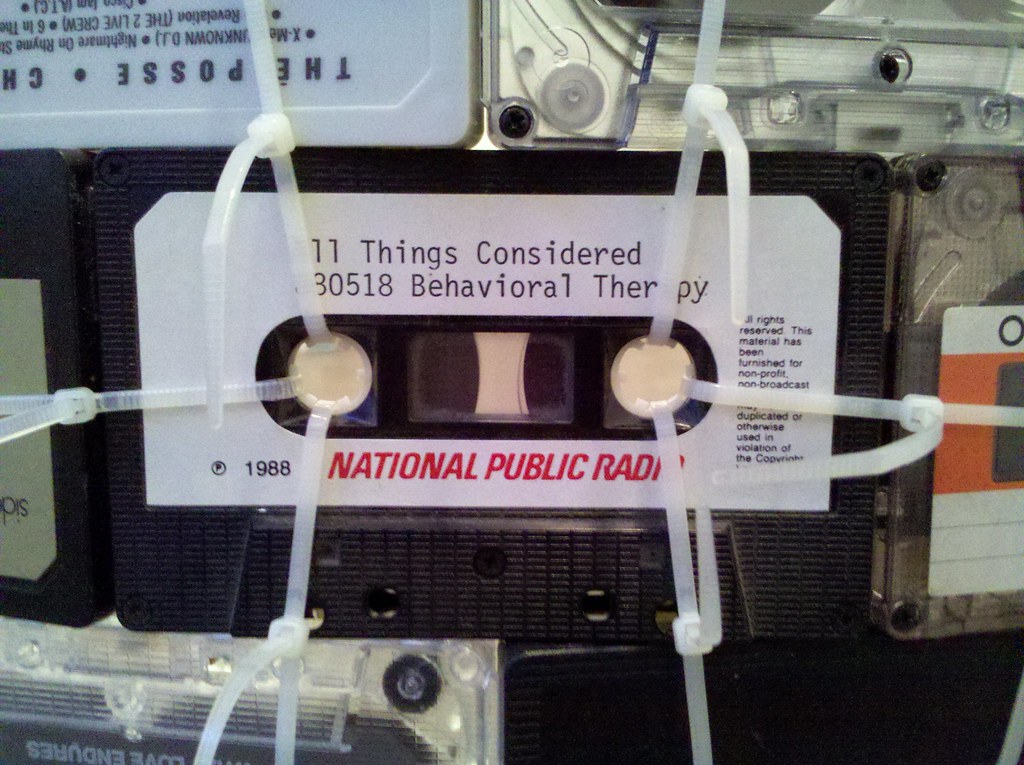

In Moebius Loop (7.4.16), Marclay used over 2,000 cassette tapes he stacked in rows and affixed them together with nylon ties. The sculpture has a nostalgic feel, a past of music of every genre played in futuristic media. The colorful and graphical effect is formed by the multiple colors of the cassette labels randomly placed.

The close-up (7.4.17) of a cassette demonstrates how he used plastic ties to attach each of the tapes. The use of tape cassettes represented Marclay's long focus and integration of music and art.

Diana Thater

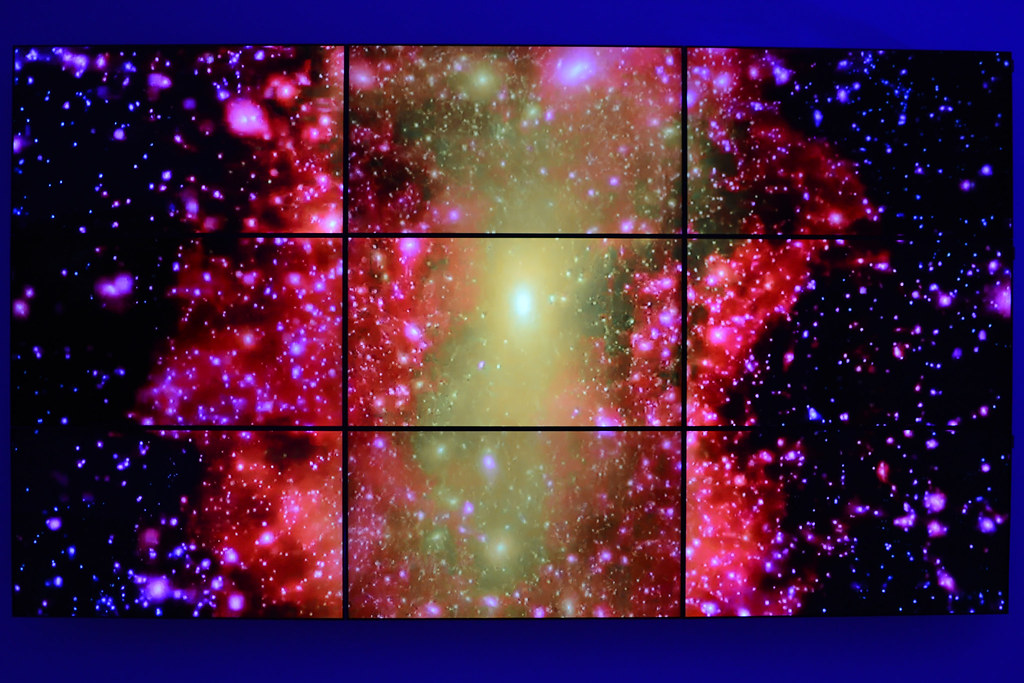

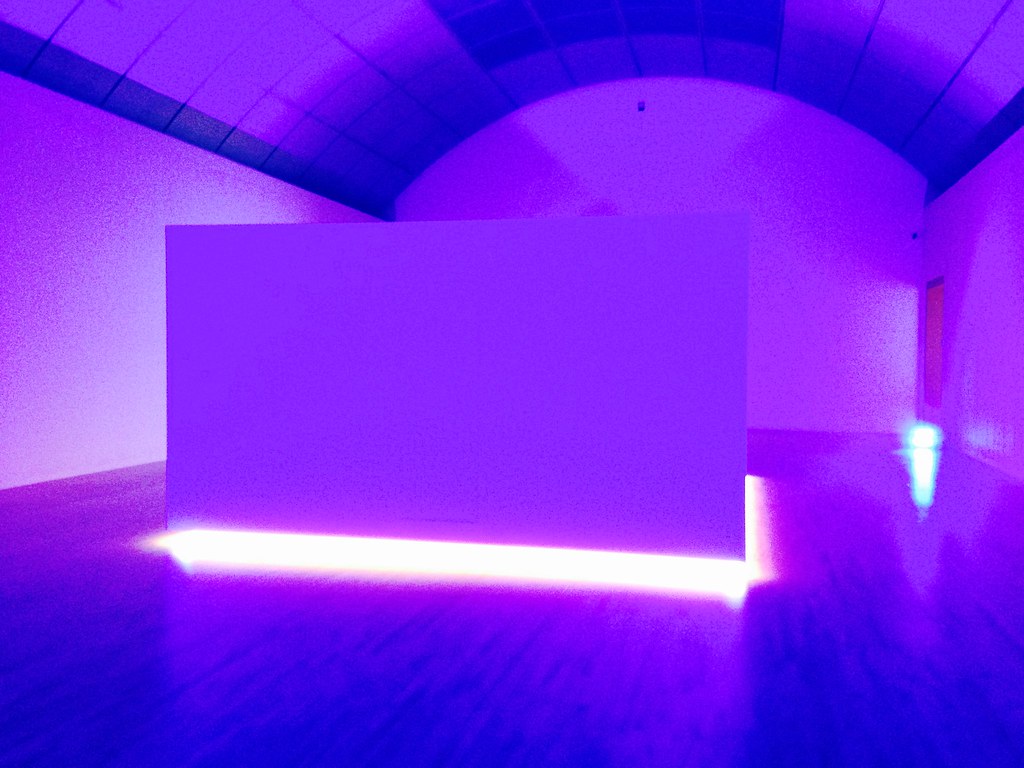

Diana Thater (1962-) was born and lives in California. She did earn a degree in Art History at New York University and an MFA from the Art Center College of Design. Thater investigates space and interaction with light and images in her video installations. She mainly explored the relationship between the natural world of nature and humans and how nature was manipulated or still maintained its original characteristics. Thater was dedicated to the interactions and relationships of those in the animal world and humans. She helped push the envelope of spatial and conceptual perceptions in the new media of video. One of Thater's major video installations, Science, Fiction (7.4.18, 7.4.19), covered multiple elements and ideas from outer space to dung beetles. She constructed two parts, one with a section containing double nine-screen monitors set on opposing walls. The monitors projected shows of the night skies from the Griffith Observatory as the room was lit to resemble the sky at dusk. In the other part, Thater erected a room-sized box emitting an odd yellow light at the base and projected dung beetles on the ceiling.

In Untitled (7.4.20), Thater placed video monitors on the floor, adding two fluorescent light fixtures. She wanted to use the concept of fragmented images, each of the videos displaying parts of the butterflies as they fly. She painted with walls of the room orange to mimic the colors found in the butterflies. The interactions of color were an essential part of the installation.

Rare (7.4.21) is another installation portraying images of endangered animals and how they are close to extinction. Thater placed sixteen monitors on the wall, each screen showing fragments of the environment and the animal's movements in its environment.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.paikstudios.com/

[2] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/e...a-hawaii-71478

[3] Retrieved from https://datebook.sfchronicle.com/art...res-dies-at-60

[4] Retrieved from https://www.qchron.com/qboro/stories...5966fe1a4.html