3.6: Expressionism (1912-1935)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174416

Introduction

At the beginning of the new 20th century, artists in Europe were dissatisfied with the academic standards and style of the art community. They began experimenting with new ideas for the modern world and expanding cities. As part of the European transformations, Expressionism was born in Germany; art charged with emotions and subject matter found in the urban settings. The director of a German museum stated, "The German artist looks not for harmony of outward appearance but much more for the mystery hidden behind the external form. He or she is interested in the soul of things and wants to lay this bare."[1]

As part of a pre-World War II change, Expressionism included art, literature, theatre, and music, fueled by young people from Germany and Russia pushing for change in the social and political structures. The movement started at the turn of the century. It continued until the 1930s when the National Socialists (Nazis) grew in power, a government rejecting Expressionism in all forms and condemned it as 'degenerate.'

The Post-Impressionists influenced the Expressionists, using bold colors and unusual forms to create expressive, exaggerated images. Instead of duplicating realistic images, the artists wanted to express inner feelings and used simple shapes and broad brushstrokes to illustrate their emotional ideas. Two different groups were dominant in the movement, Die Brucke (the bridge), led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Der Blaue Reiter (the blue rider), started by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc.

The new art styles of Expressionism flourished were displayed in museums and were purchased by collectors. In 1933, after Adolf Hitler was named to head the government, the Nazis started dismantling the artwork and removed 20,000 artworks from the museums owned by the state. "In 1937, 740 modern works were exhibited in the defamatory show Degenerate Art in Munich to 'educate' the public on the 'art of decay.'"[2] The pictures in the exhibit were hung overlapping or askew, and graffiti was written on the walls with crude sayings. The work was defined as blasphemous, art defaming women or art from Jewish or communist artists. The exhibition encouraged the people to see the art as a plot against Germany. Many of the works were subsequently destroyed, sold to make money for the government, or hidden and discovered at a much later date.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), born in Germany, studied architecture and fine art at one of the experimental art schools. He belonged to the Die Brucke (The Bridge), a group of artists who brought Post-Impressionists and Art Nouveau exhibitions to Germany. The group also started Expressionism at the beginning of the 20th century wanting to pursue nontraditional methods bridging the centuries. With the advent of World War I, he was drafted into the army, then discharged because of a breakdown, and spent time in hospitals. After the war, he went to Berlin, staying in his room, painting; others' images displayed his mental instability. He moved to Switzerland and continued to move in and out of sanitoriums, painting and making woodcuts. By 1920, he improved, and moved to back to Germany with his companion and model. His art was successful until the Nazi party rose to party in Germany, destroyed art, and shut down museums.

Kirchner used bold colors and angles, capturing modern city life as viewed in Street, Berlin (5.6.1). The local prostitutes walk down the street, talking, the men looking down, unhappy expressions. When Kirchner formed the bodies, he gave them unusual angles and forms. The dark colors are illuminated by the reflective light of the women's white accessories. The painting was one of a series he made about prostitutes.

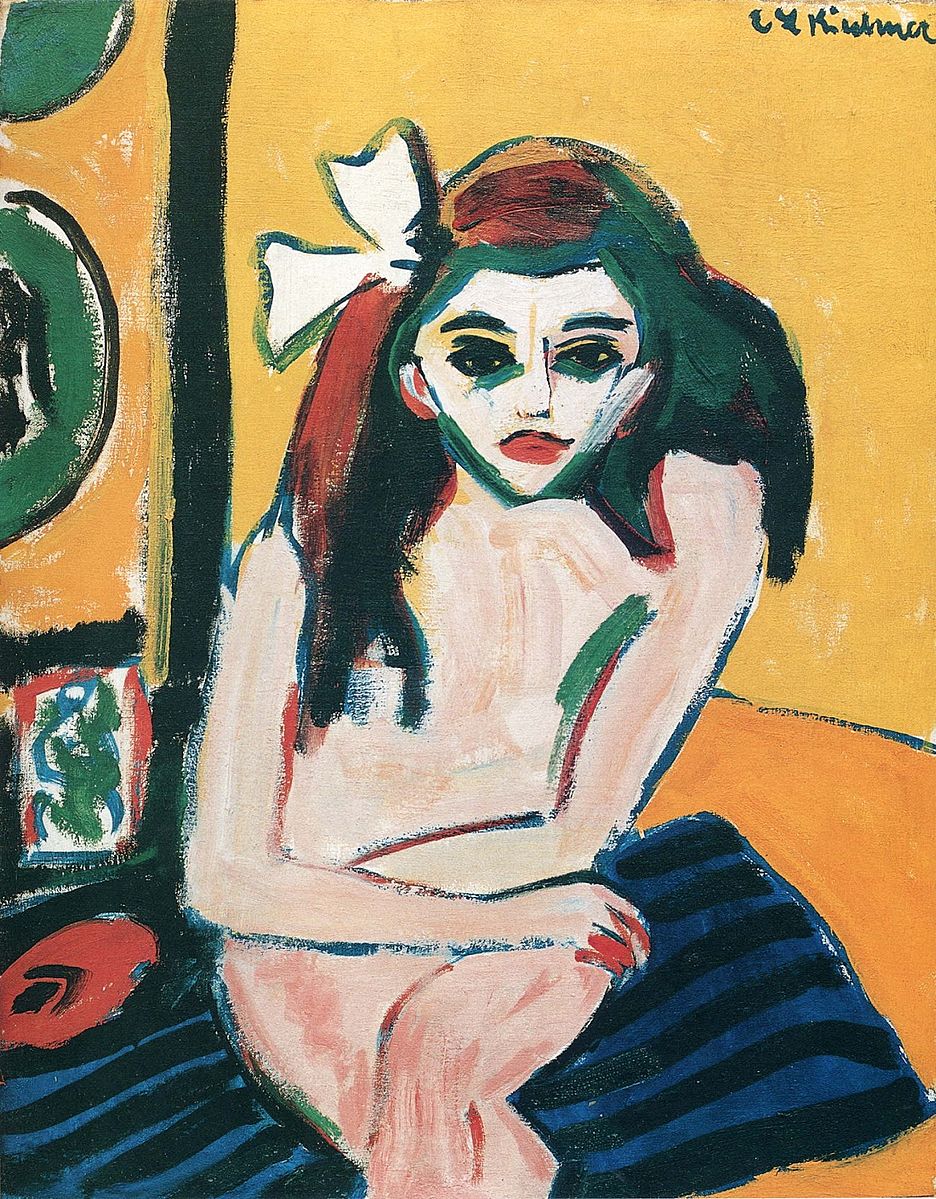

Marzella (5.6.2) is a painting of a friend's daughter he met at a lake. As part of his Die Brucke period, the young figure is composed of odd colors, sitting in an unnatural pose of angular lines. Kirchner liked to make rapid sketches of the subject, adding the colors and background after the initial sketch.

Paula Modersohn-Becker

Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), born in Germany, is considered one of the essential artists of early Expressionism in Germany. Her artistic ability was recognized when she was younger, and she trained with private instructors before going to Paris multiple times to study, including at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Although married, she and her husband frequently lived apart in Paris or Germany. She was trained in Realism and Neoclassicism; however, she abandoned those styles after being influenced by Cezanne and Gauguin and their bold colors and contours instead of the traditional realistic lines and expressed flatness. During her career, women painters seldom had nude females as models and did not paint nude females. Modersohn-Becker painted herself in many nude self-portraits, an unprecedented idea for female artists. Much of her information is from the daily entries in her diaries, frequently writing about motherhood and if she wanted children. At age thirty-one, she had her first daughter, encountered pain in her leg from an embolism after the delivery, and sadly died when the baby was only nineteen days old.

According to [Diane] Radycki, Modersohn-Becker was a "daring innovator of gender imagery"—the first woman artist to created nude self-portraits and the first to paint nude images of mothers and children. As a result, Radycki credits Modersohn-Becker as being the first modern woman artist. As she states, Modernism's style and subject matter innovations begin with his [Picasso's] Cubism and her [Modersohn-Becker's] female bodies.[3]

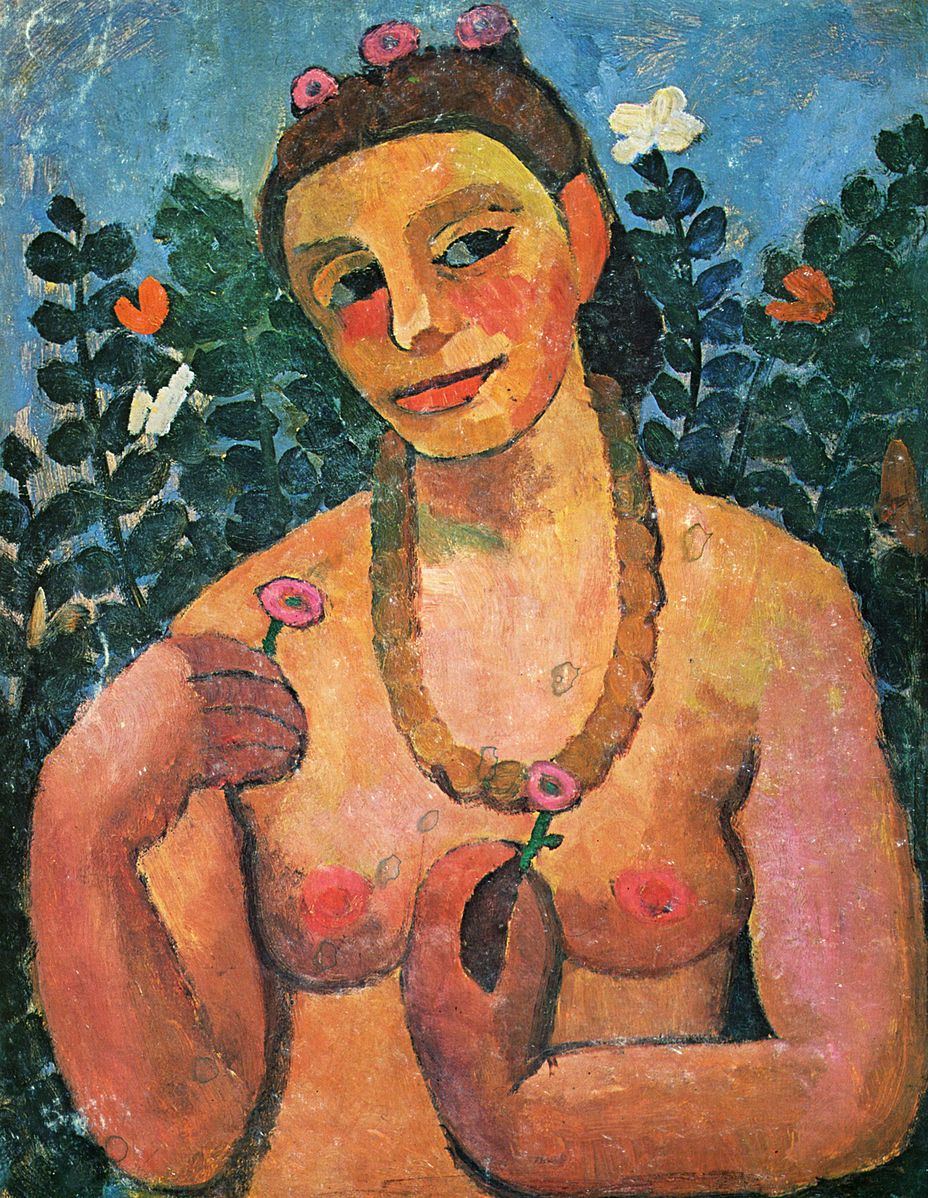

Self-Portrait, Nude with Amber Necklace Half-Length II (5.6.3) was exhibited after Modersohn-Becker's death, a painting she completed the year before. She looks straight at the viewer, not as the artist herself, but as the representative of women and their presence and beauty qualities. She is wearing an amber necklace, an object Modersohn-Becker frequently included in paintings, flowers decorate her hair, and the foliage in the background, frames the image.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Self-Portrait, Nude with Amber Necklace Half-Length II (1906, oil tempera on paper, 62.2 x 48.2 cm) Public Domain

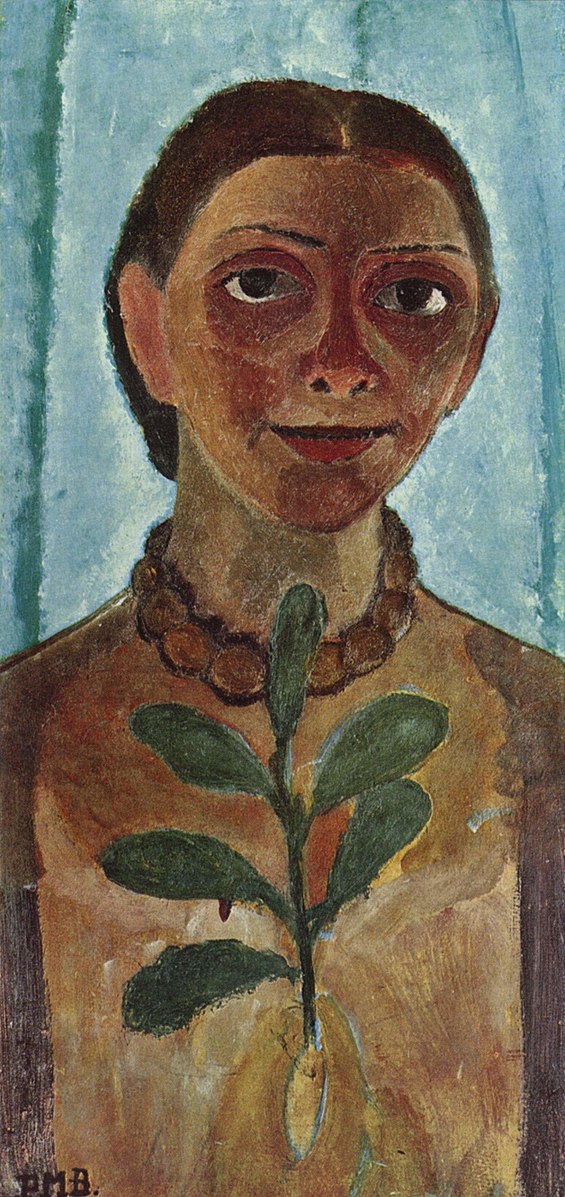

In The Painter with a Camellia Branch (5.6.4), Modersohn-Becker grasps a branch from a camellia plant, a calm look in her oversized eyes and gentle expression. She was swayed by Egyptian artwork and painted this image on wood in the same tall, narrow format used in Egyptian paintings. The face is in the shadows contrasted against the light blue background. This was the last work she painted, seven months before she died. In one of her earlier diary entries, she wrote, "I know that I won't live very long. But is that sad? Is a festival better because it's longer? And my life is a festival, a short, intensive festival." [4]

Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) was born in Moscow, a part of the Russian Empire under the rule of the tsars. Originally, he studied law at the university; however, he did not take a teaching position after graduation and went to Munich to study art. He was fascinated by color, how it was seen, and what it meant in his early life. He formed the belief that color directly influenced the soul and said, "Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, causing vibrations in the soul."[5] After studying in Munich and teaching art, he traveled through Europe until he returned to Moscow after the start of World War I. When the war ended, and the Russian Revolution overthrew the tsar, he established a museum of art in Moscow. He found himself in conflict with the materialism of the Soviet regime. Leaving Russia, he went back to Germany and taught at the Bauhaus School for over ten years until the Nazis closed it. One of Kandinsky's important early paintings was Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) (5.6.5), the speeding horse with its rider, galloping across the meadow. Rather than exact details of each element, Kandinsky used color and brushstrokes to represent the trees, the horse, the rocks, and the other parts of the scene. The viewer interpreted the painting; are there two riders or only a shadow, is the rider a child, or what is the gait of the horse. The name of the portrait was also associated with the painting concepts of the Der Blaue Reiter group he founded with artists who wanted to express spirituality through the symbolism of color. Kandinsky believed blue was the primary color of spirituality.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_52.1_x_54.6_cm%252C_Stiftung_Sammlung_E.G._Bu%25CC%2588hrle%252C_Zurich.jpg?revision=1)

Kandinsky was very focused on how geometrical planes and elements intersected to create his paintings. He believed a dot of color formed the point, to be extended into any geometric shape; the lines of the shape define the form. Kandinsky also thought color tones affected the horizontal and vertical lines. While painting abstracts, he kept copious notes on his ideas, theories, and how color defined his work. Composition VII (5.6.6) was from a set of paintings Kandinsky created over the years. Before he completed the actual work, he designed multiple sketches in both watercolor and oil. The rolling, turbulent forms of colors and shapes all have symbolic meanings, nonrepresentational boats, mountains, or figures. The central theme is the oval form overlaid by a rectangle, which historians define to represent biblical events the spiritual Kandinsky liked to portray. This painting is interpreted as the last judgment and resurrection, a virtual storm of the end before paradise.

Improvisation 27 (Garden of Love II) (5.6.7) was another Kandinsky series using abstract lines and colors to represent emotional or spiritual concepts, arousing the preconscious world. With the dark lines and masses of color, the painting depicts an embracing couple. The serpentine forms around the pair generate the idea of the subtitle, probably his reference to the Garden of Eden in the bible. In 1937, the Nazis confiscated fifty-seven of Kandinsky's paintings as degenerate art; many were destroyed.

At the Bauhaus, Kandinsky further developed his concepts of color with the addition of lines and points and the forces of lines, whether straight or curved, based on geometrical shapes with planes of color. On White II (5.6.8) used black to symbolize death and emptiness counterbalanced with white for peace and life. The other colors and lines represent other emotions, some of them sharp, others lyrical, all interwoven for life's feelings as the elongated black points slash through the geometric activities of life events.

Paul Klee

Paul Klee (1879-1940) was born in Switzerland; however, he kept the citizenship of his German father. As a young boy, he was talented in painting and music before deciding to become an artist and studying in Munich. Klee met both Kandinsky and Marc, who were part of the Der Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) group of German Expressionism, remaining a lifelong friend of Kandinsky. Klee went to Tunisia in 1914, where he felt the unique light of the country, giving him new concepts of color and how to use color outside of its standard description. After his experience in Africa, he never used models or natural scenes in his work, only abstract forms and representations to portray his subject matter. Klee went to the Bauhaus and taught for ten years, producing thousands of works until he was defined as a 'degenerate' and forced from Germany in 1933, moving to Switzerland.

Klee went to Tunisia in 1914, where he was enthralled with the light and its effects on color, making his famous statement, "Color and I are one. I am a painter."[6] Hammamet with Its Mosque (5.6.9) was painted from the exterior of the city ramparts. The image is created as many of his works; the upper section of the paint represents the gardens and towers while the lower are nonrepresentational, composed of transparent geometric shapes of multiple colors.

.jpg!Large.jpg?revision=1)

Temple Gardens (5.6.10) was also painted after he visited Africa. Klee used watercolor to paint the garden with the look of stained glass. Some of the high walls, doors, domed towers, and palm trees fill the paper with the bright colors he found in the Tunisian light. Klee was not afraid to alter his work; scissors cut the painting into three sections and moved the original middle section to the left side to achieve the balance he wanted. Klee liked to create a composition that has a story associated with the lines and color tones.

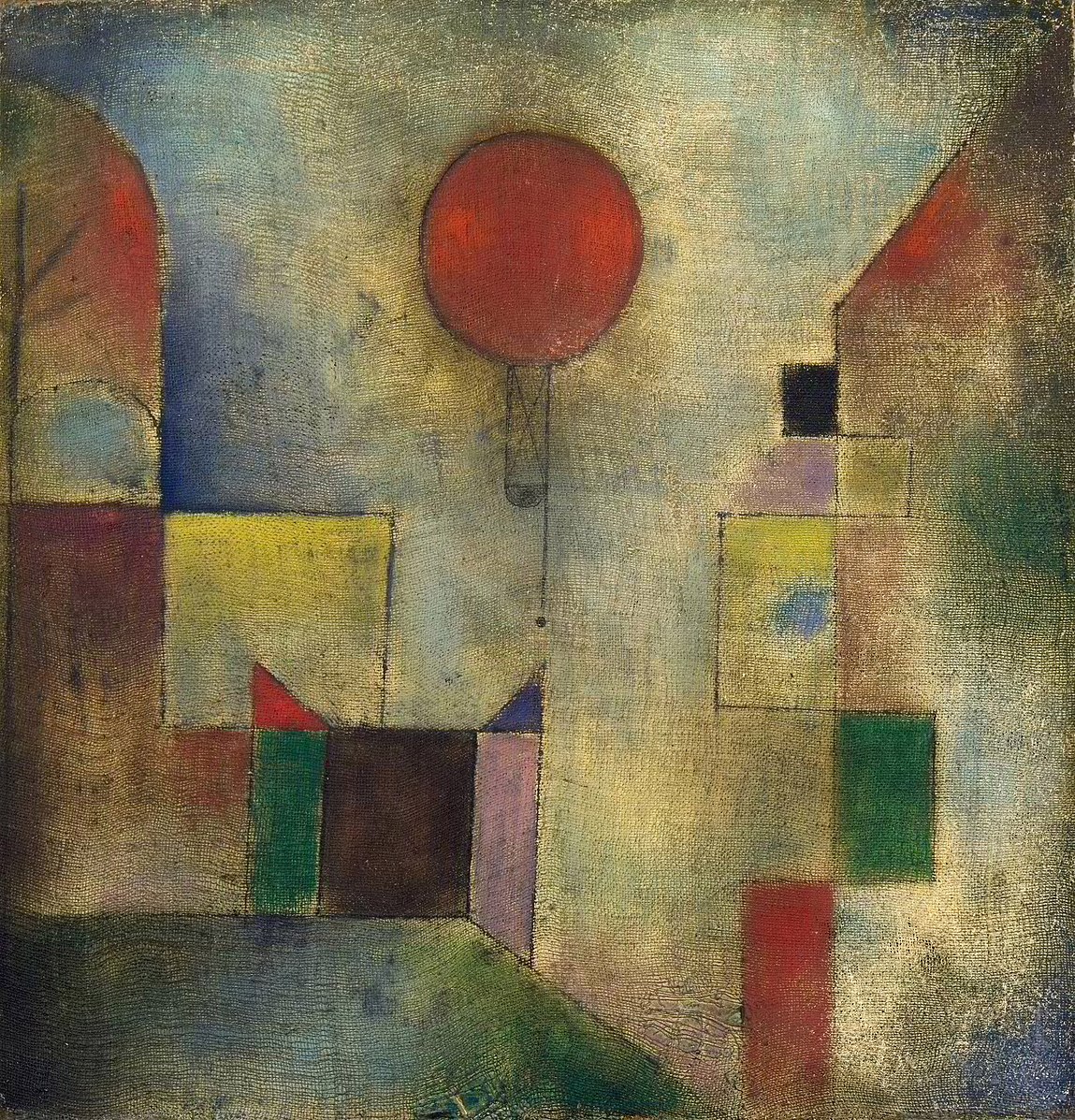

Red Balloon (5.6.11) is a set of softly colored geometric shapes that form the cityscape with the loose balloon floating upward, the circular balloon against the rectangular city. He carefully balances the red color of the balloon with parts of the buildings in red, moving the eye around the painting. For this work, Klee mounted gauze primed with chalk on a board and then painted with oils. In 1938, Klee lived in Switzerland and suffered from a debilitating disease, making it difficult for him to paint. He created seven different panels using charcoal and oil on ordinary newsprint pasted on linen or burlap. The result was an unusual surface, and old news, ads, or editorials from the newsprint were still visible in some places. His signature elements were the thick, dark lines.

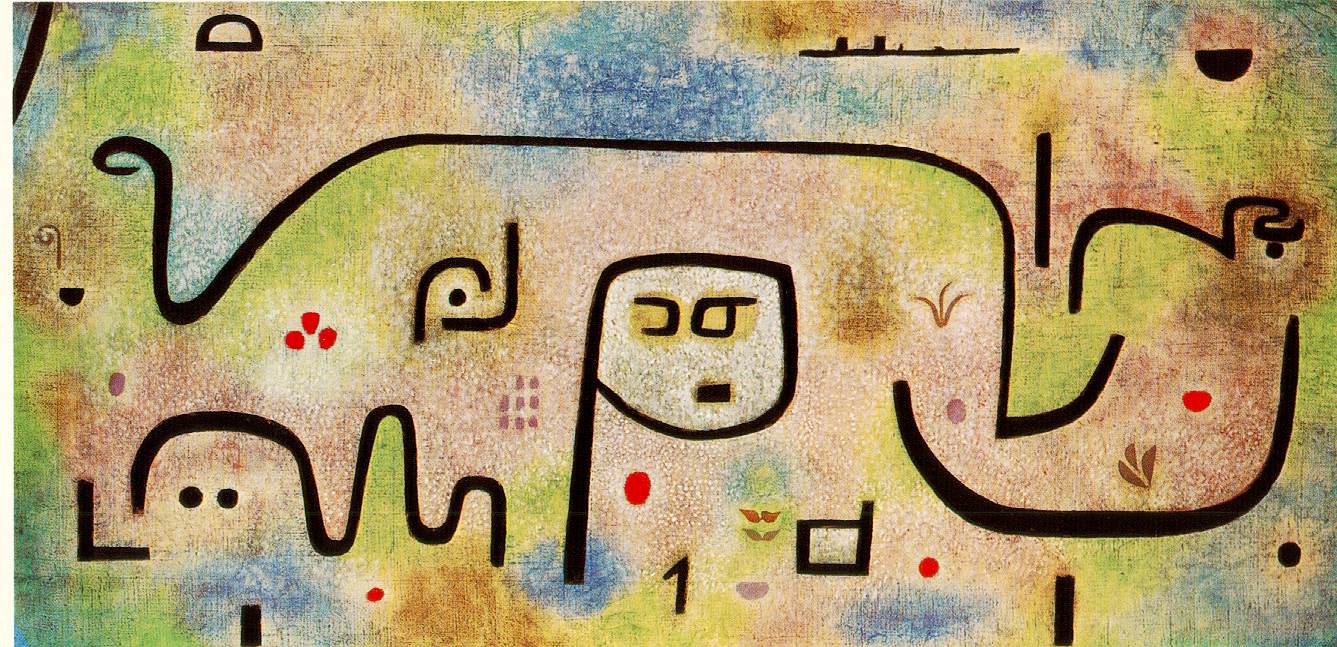

Insula dulcamara (5.6.12) represents an island formed by the lines, a passing ship, the sun rising, and the moon setting, all supported by the light colors of spring. However, one researcher examined Klee's writings and biography and stated, "the painting's black markings are configured as a graphical abstraction of the name 'Paul Klee'; the configuration as a whole constituting the artist's signature."[7]

Franz Marc

Franz Marc (1880-1916) was born in Munich, enrolling in the arts program at the university before going to Paris, meeting and studying with some artists, especially van Gogh. After returning to Germany, he successfully exhibited his work, animals his primary vehicle to express emotions. When World War I started, he was drafted into the German Army, sent to France, and killed during the Battle of Verdun. During the Nazi rule in Germany, Marc was listed as 'degenerate,' and many of his paintings were destroyed or hidden. Some of his work was found as late as 2012. Marc was highly influenced by Kandinsky, especially the use of color in nontraditional ways. Marc's world was in turmoil before the beginning of World War I. With Kandinsky, he started Der Blaue Reiter, a group that focused on color and abstraction to project their concepts about the problems in the world. Animals became the tool Marc used as the symbols, painting them in colors to symbolize his meanings. In 1910, he wrote to another artist; "Blue is the male principle, astringent and spiritual. Yellow is the female principle, gentle, gay, and spiritual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy and always the color to be opposed and overcome by the other two."[8]

In Blue Horse I (5.6.13), the horse is painted in different tones of masculine blue, standing on one of the hills depicted in different colors, a yellow mist forming in the valleys. The horse seems to float above the red ground, somewhat freed from gravity, its legs standing on different hills. "…the blue fore and hind legs of the horse upon an area composed solely of shades of deep red and violet…We can see the actual application of Marc's color symbolism.[9]

The Tower of Blue Horses (5.6.14) is painted with the four horses arranged vertically, the lines on the first horse clearly defined, and the leg on each ascending horse-drawn in a vertical line. The heads of the horses are turned as though startled by an impending threat. A series of lines and colors depict mountains in the background. The painting was hung in a museum in Berlin until confiscated by the Nazis. In 1937, they hung the painting in Munich marked as 'degenerate.' Hitler had the painting removed from the show, and has been lost to history since then.

Marc painted The Yellow Cow (5.6.15) shortly after his marriage as a tribute to his wife; yellow was the color of Marc's idea of femininity, and his new wife gave him the security he was seeking. Spots of blue, the color of masculinity, add the unity of the two people. The cow dominates the scene, and a smaller group of red cows blend into the red landscape. Marc liked to use repetitious colors and shapes; blue mountains resemble the cow's haunches, and the strong diagonal, thick lines of the trees mimic the cow's stance.

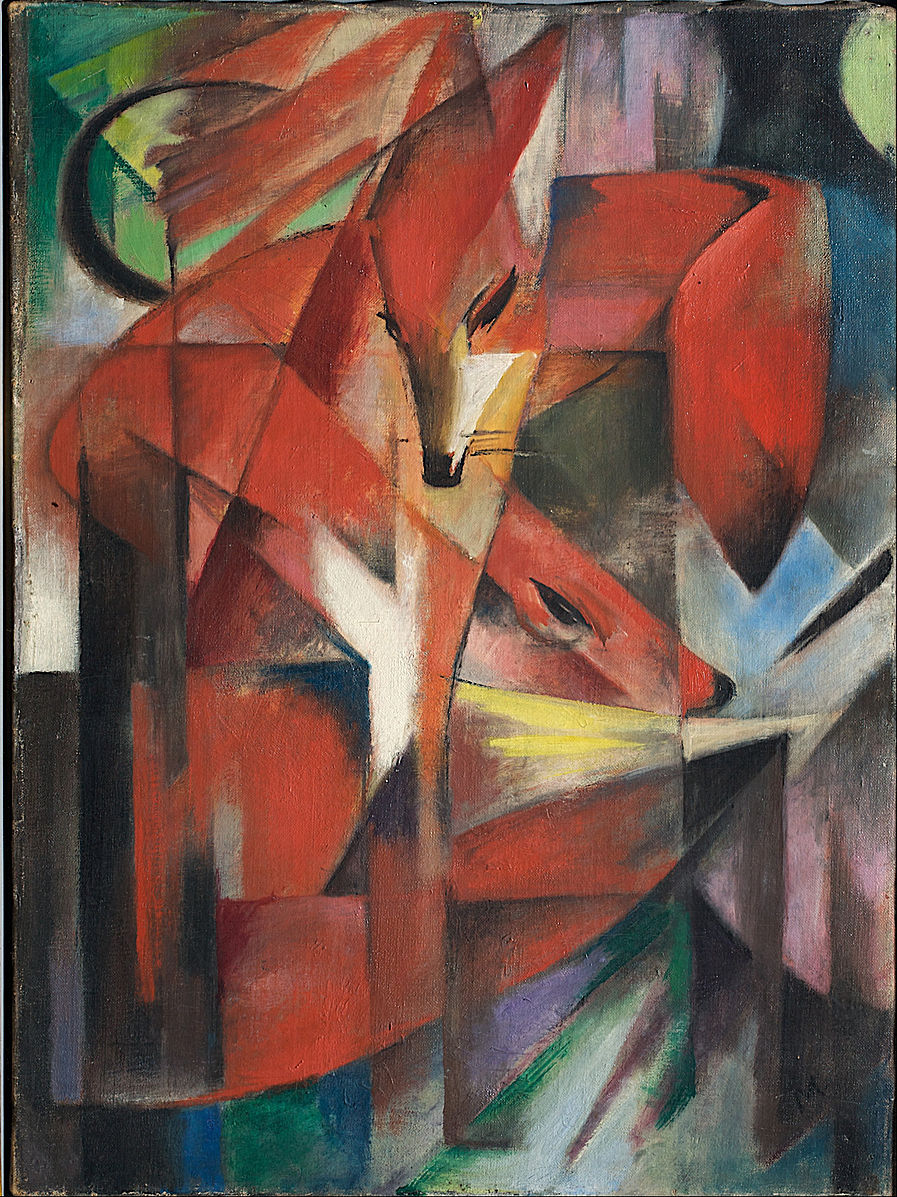

The Fox (5.6.16) was a typical figure Marc painted, an animal he considered fierce, as demonstrated by his prominent broken brushstrokes and vibrant colors. The white on the foxes' face form a focal point in the animated grouping of their bodies, impossible to discern how many are included. The painting is composed of geometric shapes reassembled in the wrong places.

Marianne Werefkin

Marianne Werefkin (1860-1938) was born in Russia and started as an art student early in her life. However, during a hunting excursion in her twenties, her right hand was shot, making it difficult to use, only recovered through persistent practice. When she married and moved to Germany, she suspended her painting until her late forties. She exhibited with a group of Expressionist artists, including Kandinsky and Marc. With the advent of World War I, she moved to Switzerland, where she remained. One of the few women artists, her work was abstracted yet expressed how she felt about the human spirit, people set in scenes, hunched over, frequently displaying their poverty. She wrote about life in her diaries and once said,

One life is far too little for all the things I feel within myself, and I invent other lives within and outside myself for them. A whirling crowd of invented beings surrounds me and prevents me from seeing reality. Color bites at my heart.[10]

Werefkin painted her Self-portrait (5.6.17) when she was in Germany and part of the Expressionist group. She used deep greens and blues for the background with broad brushstrokes to contrast with the other colors of her face and clothes. She was heavily influenced by how the Post-Impressionists used color and painted dynamic colors to portray emotions and intensity. Some historians deem her self-portrait as one of the more extraordinary self-portraits in art.

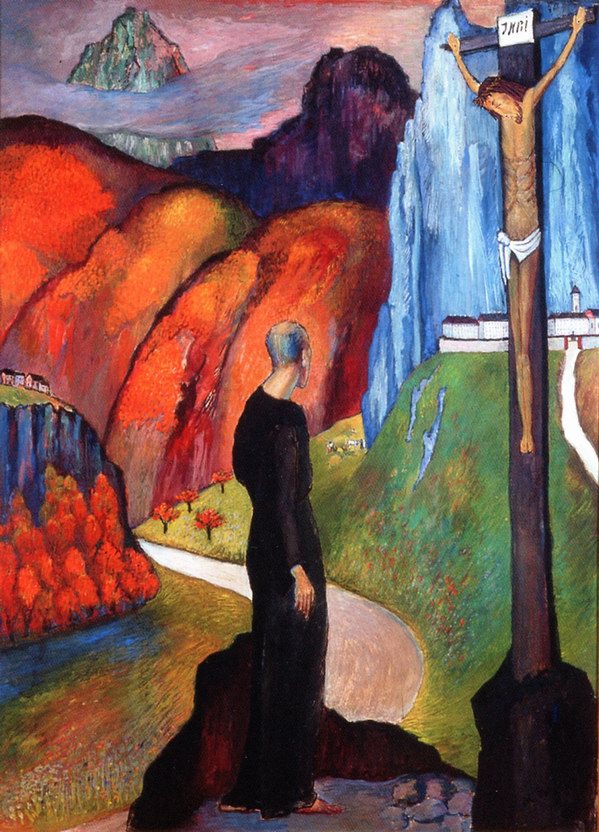

The Monk (5.6.18) reflected her interest in religion and the symbolic nature of religious concepts and icons. The crucifixion is found in many of her later paintings. The cross against the bright blue of the ethereal world is balanced against the dark or bold colors of the natural world inhabited by the monk. The mountains reflect her view of the world in Switzerland, a winding road through the mountain pass, the monk appearing to focus on the road and reality instead of the cross and the suffering it implies. The bright reds and oranges are balanced by the dark purple mountain in the center and the soft blue on the right. The monk wears dark clothing, bringing a profound depth to the painting as he looks down the open road.

Expressionism was developed at the beginning of the century by artists who wanted to add the emotions of their inner feelings and ideas, distorting the reality for the passion of feelings. The application of color and brushstrokes became their signature, developing images as the precursor to modern art. The time was also part of the upheaval of world wars and political disorder.

[1] Kirchner – Expressionism and the City, Royal Academy 2003. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/2007pdf0926234509/http://static.royalacademy.org.uk/files/kirchner-student-guide-13.

[2] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3868

[3] Retrieved from https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2893&context=gc_etds

[4] Retrieved from https://arthistoryproject.com/artists/paula-modersohn-becker/self-portrait-with-a-camellia-branch/

[5] Kandinsky, W. (1911). Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Translated by Michael T. H. Sadler (2004). Kessinger Publishing, p. 25.

[6] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/483158?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=paul+klee&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=40

[7] Pike, C. (2014). Signing off: Paul Klee’s Insula dulcamara, Word & Image, 30. 117-130.

[8] Retrieved from http://www.franzmarc.org/Yellow-Cow.jsp

[9] Moffitt, J. (1985). "Fighting Forms: The Fate of the Animals." The Occultist Origins of Franz Marc's "Farbentheorie". Artibus Et Historiae, 6(12), 107-126.

[10] Retrieved from https://www.lenbachhaus.de/collection/the-blue-rider/werefkin/?L=1