10.2: Contemporary Figurative (21st Century)

- Page ID

- 212970

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Figurative art based on people and stories has become a dominant part of the art world. Although figurative work has been created for centuries, contemporary styles are new, innovative, and non-traditional. Global boundaries are gone, and the standards for European-Western art are jettisoned. Figures become reconstructed, paint jumps and slashes across the image, and colors are bright and conflicting. The designs, styles, and imagery vary; however, a few themes cross through the work. One central theme resounding through the artwork is color; it is bright, colorful, and mixed. Another reverberating concept is exploring cultural identity, racism, and heritages. Since the early 2000s, figurative art has exploded worldwide, emphasizing identity politics.

Women artists are using the figure to challenge current old stereotypes and the sexual portrayal of women throughout history. Women now feel free to manipulate the image of the female body in their views. They use exaggerated features or contort the figure in ways understandable to other women. Much of their work is based on domestic settings and events in a woman's world. They use narratives in contemporary culture, exploring sexuality, identity, and humanity. Artists of color seldom see images of their culture as significant figures in historical portraits. Now they are increasingly visible and changing the dialogue of figurative artwork to be inclusive and represent multiple cultures. Artists in this section:

- Amy Sherald (1973-)

- Njideka Akunyili Crosby (1983-)

- Dana Schutz (1976-)

- Nicole Eisenman (1965-)

- Wangechi Mutu (1972-)

- Chantal Joffe (1969-)

- Claire Tabouret (1981-)

- Michelle Gregor (1960-)

- Chiho Aoshima (1974-)

- Jylian Gustlin (1960-)

- Hollis Chatelain (1957-)

- Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (1977-)

Amy Sherald

Born in Georgia, Amy Sherald (1973-) was drawing images from when she was a child. When she went to a museum on a school field trip, Sherald discovered art was a profession. Her mother wanted her to become a doctor, which increased her determination to pursue art. Sherald was among the few African Americans in her classes, and she became aware of race early. As an artist, she wanted to create different chronicles of the lives of African Americans. Sherald received her BA from Clark Atlanta University and an MFA from Maryland Institute College of Art. She paints typical members of African American families in their day-to-day lives. Using a grisaille technique for skin colors, Sherald uses grey as the base and applies it in a very thin, watered-down approach with a brush. Adding small amounts of black, she creates shadows and highlights to produce her distinctive portraits and black identity. Sherald paints with a vibrant palette for highly contrasted clothing. Her backgrounds are usually a single color and undefined, allowing the person to stand out. Each person is dramatically posed and looking directly at the viewer.

Michelle Obama was the First Lady of the United States from 2009 to 2017, and every first lady selects an artist to paint the official portrait for the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery. Obama chose Sherald to paint the official painting entitled First Lady Michelle Obama (10.2.1). Obama is sitting, looking at the camera in a reflective mood, her chin resting on her hand. The distinctive geometric patterned dress flows outward, almost filling the bottom part of the painting. The unique colors on the dress form quilt-like patterns like those made by the Gee's Bend quilters, the descendants of enslaved people. Sherald took photographs of Obama to reference when she was painting. She painted Obama's skin in a basic grayscale in her usual grisaille method. The bright robin's egg blue background brings a high contrast to Obama. The director of the National Portrait Gallery, Kim Sajet, stated, "Portraiture used to be seen as this old-fashioned, fuddy-duddy, really for dead white people kind of way of painting…and they've completely changed that and put it on its head."[1]

Sherald painted ordinary people and posed them for her unique portraits. The Rabbit in the Hat (10.2.2) and The Make Believer (Monet's Garden) (10.2.3), the people are posed straightforward-looking at the viewer. The man in his florescent striped jacket, bright turquoise blue tie, and impeccable white shirt and pants appear almost surrealistic as he oddly holds a rabbit in his hat. The mottled green background highly contrasts with his boldly striped jacket. The woman is highly juxtaposed against the brilliant orange-red background in the other painting. Her bright green dress is covered with yellow and pink flowers resembling Monet's repetitive use of flowers. Her eyes are closed, perhaps resting or ignoring the viewer's look. With both paintings, the backgrounds give no clue about the person or where they may be standing, a trademark of Sherald.

The Bathers (10.2.4) portray two women supposedly at the beach. They are wearing swimsuits, and the background is a vivid blue; however, their location is not evident. Western painters of people at the beach or pool always incorporated elements of their site; sand, waves, or splashing water. However, Sherald always sets her portraits against a single color, unknown background, leaving the viewer to imagine where the people are standing. Only the purple bathing cap on one woman's head divulges any clue about where they are. Both bathers look outward, waiting for the viewer to engage in conversation. Sherald chose her models from everyday life and stated, "When I choose my models, it's something that only I can see in that person, in their face and their eyes, that's so captivating about them."[2] When a portrait of the bathers is hung on the wall, it is low to the ground so the viewer meets them at eye level.

An exhibition in New York City by the artist whose painting of Michelle Obama became a sensation features portraits of everyday models and captures the private, inner lives of African Americans. "Sunday Morning" producer Sara Kugel reports.

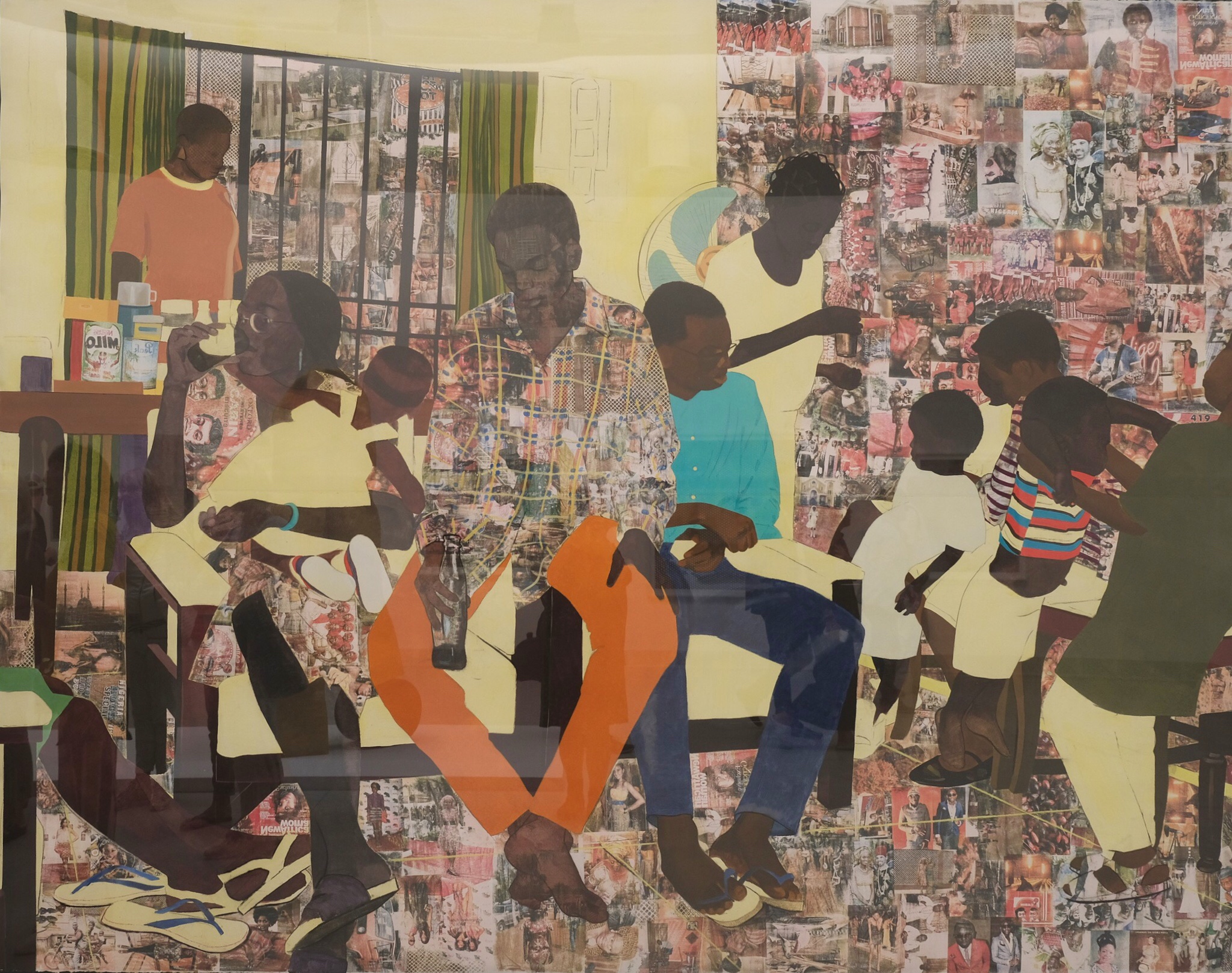

Njideka Akunyili Crosby

Njideka Akunyili Crosby (1983-) was born in Nigeria of Igbo descent. Her mother was a professor at the University of Nigeria, and her father was a doctor. When Crosby was in high school, the family obtained a green card for the United States. She and her sister came in 1999, studying for American tests before college. Crosby graduated from Swarthmore College, where she studied both biology and art. Initially, she planned to become a doctor until deciding to change to art in her senior year. Crosby creates her images based on the culture and social life of a Nigerian woman who lives in the United States. She incorporates fabric, paint, colored pencil, and printed photo transfers into her work to achieve different looks from her culture. Crosby regularly took photos of her family in Nigeria and used them to make the acetone-transfer prints. She also places women in the center of power during interactions with others, including the ideas from interracial marriage.

Before Now After (Mama, Mummy, and Mamma) (10.2.5) depicts the interrelationships in her family. Her sister sits at the table in a bright pink shirt, surrounded by images of her mother and grandmother. The paintings sit on the table instead of hanging on the empty wall, the wall a counterpoint to the opposite wall filled with pictures. The group of objects in the center of the table almost looks like a still-life, a second painting within the painting. Crosby uses a calm color palette with muted blues, pinks, and browns, bringing the two contrasting colors together.

The painting Nwantinti (10.2.6) is based on an Igbo love song. The two people in the painting appear in a private and silent moment, the man lying on his back, his head cradled on her lap. The image is one of Crosby herself and her husband presenting the mixture of race and gender, each wearing the style of clothing found comfortable by their cultural backgrounds. The painting is almost all tones of red and black. Only the blue on the photo transfers punctuates the room with spots of color. Crosby incorporated her personal images and photos into the bedspread, rug, and background collages. The strong trellis pattern on the paneled wall helps ground the floating images in most of the room.

The painting 5 Umezebi St., New Haven, Enugun (10.2.7) depicts a family gathering. Crosby used her photo-transfer images to create the floor and wall, anchoring the bottom and side of the painting and providing the background. The photos in the window give depth to the image as though looking out the window and up the hill. The shirt and dresses of the adults are also photo transfers, distinguishing them from the rest of the family. Crosby used yellow to pull the viewer across the portrait and examine what each person is actively doing. The seated man's orange pants and the boy's blue shirt consistently bring the viewer back to the center. Each person's activities convey a significant amount of movement to the painting.

Nigerian-born painter Njideka Akunyili Crosby often grapples with dual ideas of home in her work. She discusses how she studied European figurative painting at an art academy but now uses her traditional training to invent, transform, and express her uniquely hybrid point of view.

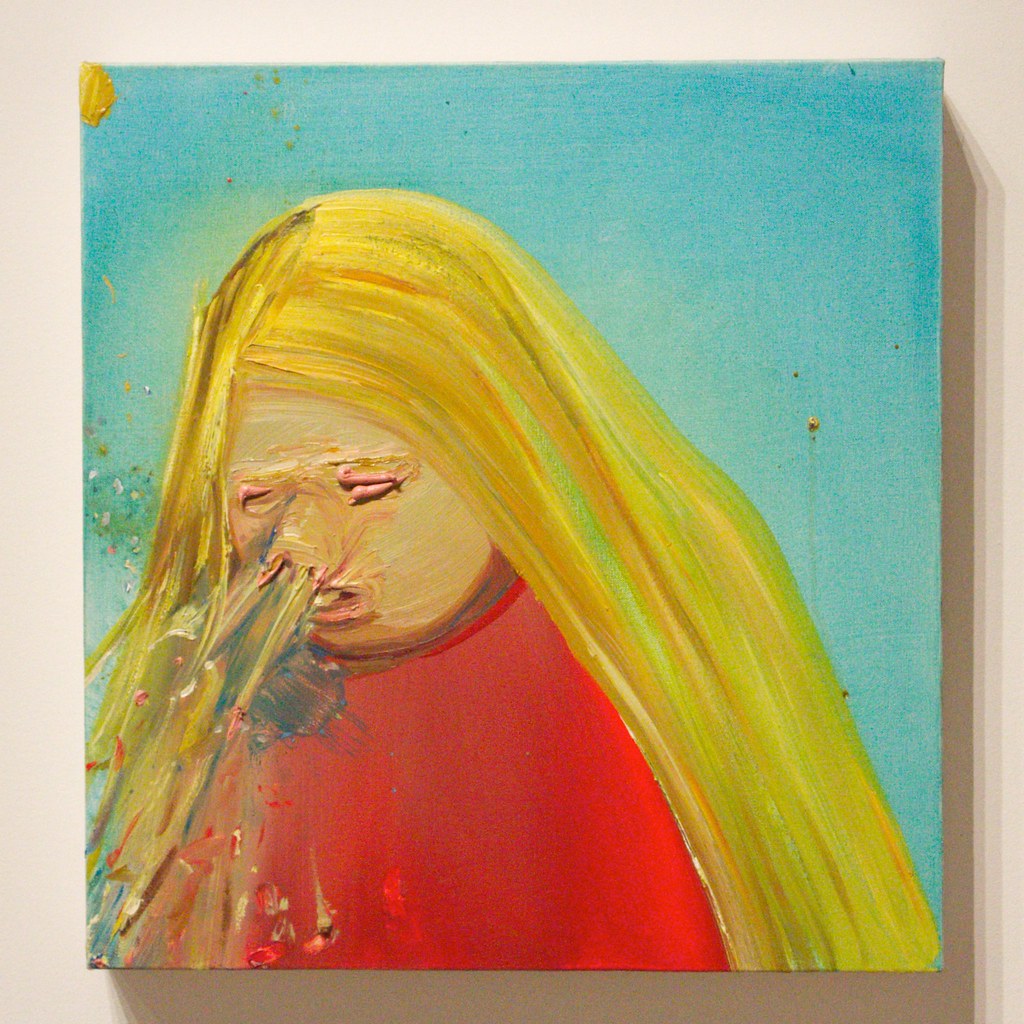

Dana Schutz

Dana Schutz (1976-) was born in Michigan. Both of her parents worked in the local schools. Schutz attended different art schools and received her BFA at Cleveland Institute of Art and her MFA from Columbia University. Her figurative paintings frequently portray people in awkward or controversial situations. Schutz's work is often ambiguous, emotional, and complete with complicated tensions. Her work is not just fantasy; the images may become plausible realities as she adds abstraction to her figuration. Some of her figures are comical, while others are on the edge of violence. Schutz uses oil on canvas and acrylics with large, loose brushstrokes. Schutz is adventurous with color and incorporates an extensive color palette for each painting. In Men's Retreat (10.2.8), Schutz imagined how the top executives in powerful corporations interact in the middle of the forest. Three men were still dressed in suits, although they had loosened their ties, some had changed to casual clothes, and a few had removed all clothing. The painting imagines how these prominent executives acted by playing bongo drums, face painting, playing trust games, or the blind leading the blind. Schutz used a broad range of colors layered in transparency, suggesting the executives who used to control now fumble in the haze of the trees or flowers in an unfamiliar and uncontrolled environment.

Sneeze (10.2.9) is typical of something everyone does; however, not so obvious or an uncontrolled scene of the high-velocity sneeze and repulsive drooling. Schutz exaggerated an embarrassing event giving the image an almost comedic interpretation. The person's nose is also exaggerated, enhancing the amount of snot propelling from the nose. Schutz used primary, bright colors drawing attention to the person and the disgusting debris now covering the red shirt. Thick rows of paint force the eyes closed, unable to see the disaster unfolding. Shaving (10.2.10) portrays a woman shaving her pubic hair, generally performed in private. In this image, the woman sits on a public beach, unworried about who is passing by. The painting is composed in a format similar to Cubism, only using rounded shapes and less fracturing. Almost comically, the woman's head is facing the opposite direction, watching the ocean view instead of where she is shaving. Schutz left the oversized container of shaving cream, spilling continuously. The two tilting trees and the large yellow hat frame the woman. The rounded body offsets the hard square lines of the shirt and blanket.

In her Brooklyn studio, Dana Schutz imagines the moment when a painting becomes “more than just material, and more than just a picture.” She describes how her paintings begin as absurd moments and evolve as bodies with their logic.

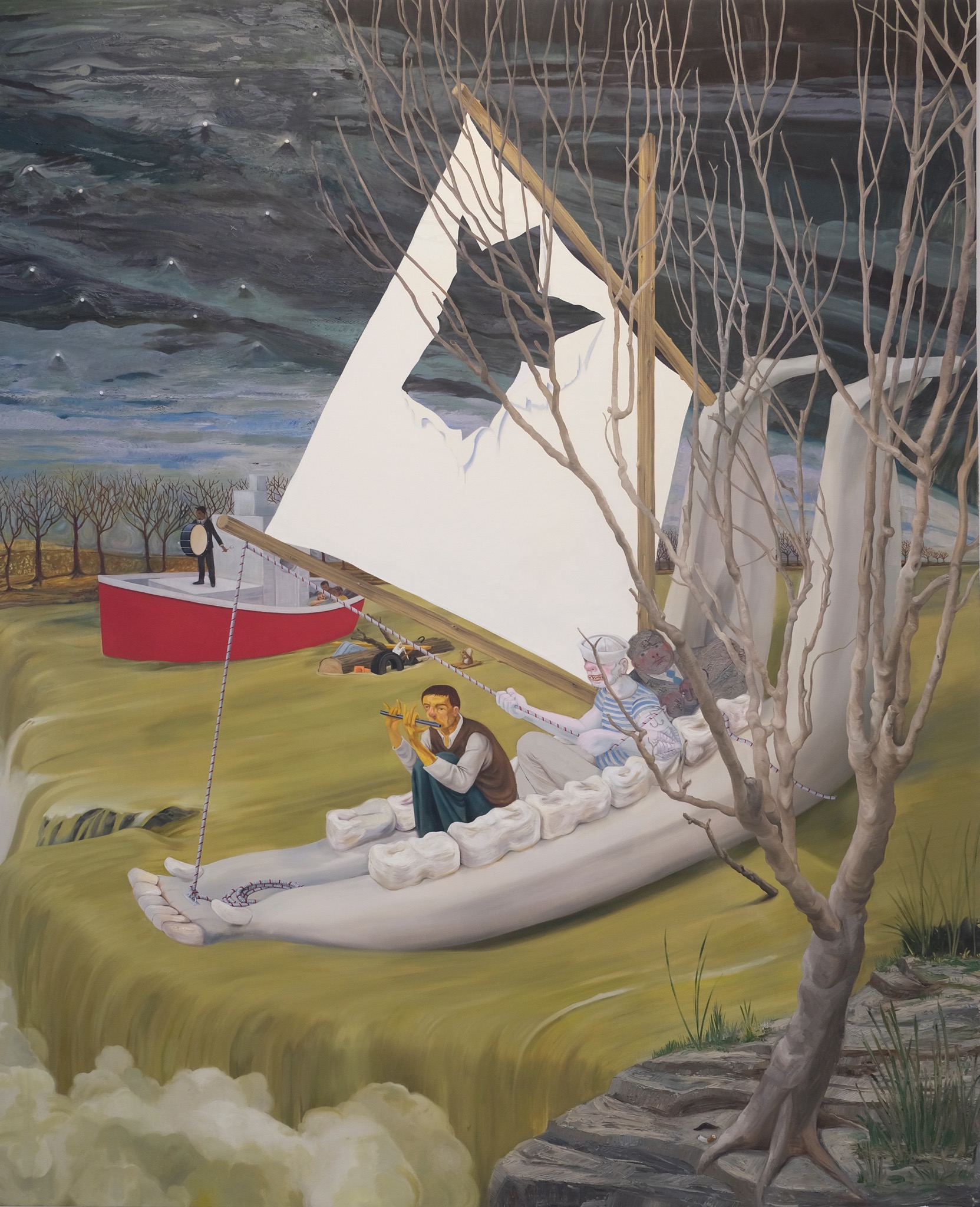

Nicole Eisenman

Nicole Eisenman (1965-) was born in France before her family moved to New York in 1970. She graduated with a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design. Eisenmann taught at Bard College for six years. She is known for her figurative paintings based on conflicting themes of sexuality or comedy, sometimes humorous and other times dark. Although painting is her primary medium, she also creates prints and sculptures. Eisenmann's paintings frequently distort body parts like hands, feet, ears, or noses. Her work is energetic; she uses intense colors to create figures in groups or alone and often reflects on herself. Eisenmann identifies her work as gender-fluid and generally uses the pronoun "she" to subvert social norms. Eisenmann uses friends as models whose gender is not resolved at the pronoun level. [3]

The Breakup (10.2.11) is an image of a cartoon-like figure looking at a phone in disgust and disbelief. The figure's ears burn with a bright orange, the mouth downturned. The phone is held directly in the viewer's face, blaming the phone for what happened. One eye appears alarmed and angry about the message, while the other is seemingly saddened. Heading Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass (10.2.12) is an immense portrayal of three men on a boat composed of the lower jawbone, the giant mandible. A quarter of the sail is torn away, leaving a gaping hole. The fast-flowing water moves the ship, soon dumped over the waterfall. The leading man in the boat plays the flute, the second man pulls the rope hoping to use the nonfunctioning sail, and the third man sits in his suit. The red ship also floats towards the waterfall, the man standing and beating the drum. The ships on the decaying yellow-green water are filled with people focused on their interests as the entire country falls.

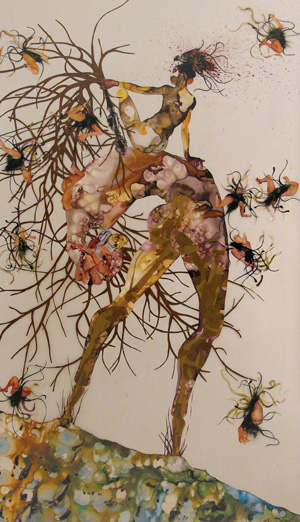

Wangechi Mutu

Wangechi Mutu (1972-) was born in Kenya and moved to New York in the 1990s. She received her BFA from Cooper Union for the Advancement of the Arts and Science and an MA from Yale. Her primary focus was on the female body, especially the violence and misrepresentations of today's Black women. Using multiple media and abstracted depictions, Mutu's figures may look otherworldly while displaying the objectification of the female. Mutu also examined the results of environmental destruction and natural beauty, creating fantastical landscapes. She wants viewers to look at her mythical images and discover different cultural and globalist interpretations. Mutu uses multiple mediums, including painting, sculptures, collages, and videos, and integrates the media.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City was enlarged 117 years ago, and the façade on the front of the building included niches for statues. However, the museum had no money to purchase anything, and the niches were empty for all those years. Mutu was commissioned to create statues, and she was interested in the caryatids, or the carved female bodies used to support buildings. Mutu created four bronze figures entitled, The New Ones, Will Free Us, representing activists, environmentalists, immigrants, and others who bring new ideas to the world's problems. The Seated I (10.2.13) and The Seated III (10.2.14) are two of the four statues. The cast bronze figures were kneeling and encased with coils wrapping around their bodies; only the arms and head were free. Mutu used polished discs and positioned them on the face or the head. The discs resemble different embellishments African women wore as lip plates, necklaces, or other beading. Mutu liberated women from the historical work of supporting others. "Belonging to no one time or place, The Seated I and III are stately, resilient, and self-possessed, announcing their authority and autonomy."[4]

Go behind the scenes with contemporary artist Wangechi Mutu, who discusses the inspiration and making of The NewOnes, will free Us, an exhibition of four sculptures that inaugurate The Met's annual facade commission.

Mutu used unusual mixed media, including cutouts from medical newsletters, clothing magazines, ethnographic writings, and pornographic magazines. She took parts of the images and reassembled them. Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumors (10.2.15) comprises images from a nineteenth-century set of medical illustrations. The different images defined and illustrated diseases found in each female sex organ and the title from the medical book itself. Mutu used collage pieces, torn paper, tape, or glitter to make individual faces. The information in the original medical book was interpreted and written by men who knew little about women's issues, and the fantasy of the faces reflects that knowledge.

You tried so hard to make us away (10.2.16) was inspired by the religious hymn Amazing Grace. The song was written by a slave ship captain who later became a minister and supported the abolitionist movement. Mutu stated, "The important thing for me about Amazing Grace is that it is rooted in the mud and injustices of a dark, convoluted past, and yet it has become the most redemptive and ubiquitous of hymns ever... thanks to colonization, missionaries, and the translation of the song into every imaginable language."[5] The work was based on the mangrove tree, a plant common along shorelines worldwide. The mangrove grows in brackish waters where freshwater rivers flow into the seas. The tree has existed for thousands of years and survived hurricanes, winds, floods, excessive salt water, and other harsh conditions. The mangrove became a metaphor for Mutu and the survival and growth of African people sent to the Americas as part of the slave trade. The more prominent figure is rooted to the ground as another figure emerges, smaller figures flying away, like seeds taken by the wind to land and grow, the resilience of the people and the mangrove tree. Mutu uses ink and other multi-media materials for the image.

Chantal Joffe

Chantal Joffe (1969-) was born in Vermont; her mother was also an artist. Joffe received her BA from Glasgow School of Art in Scotland and an MA from the Royal College of Art. She remained in England after school and lived in London. Joffe generally portrays women or girls in her work. She selects images from photographs, different types of magazine pages, or even self-portraits. Joffe's work is massive, conflicting with the intimate images she creates on the oversized canvases. The females in her paintings are honest, denying the ideals of female objectification. Many women in her work are young, on the edge of their potential, without giving them the expectations of the female form. Joffe adds patterns and stripes to the clothing in her paintings because she likes how it brings a sense of fashion to their clothes. Motherhood inspired Joffe to follow her daughter's life in paintings and how being a mother transformed her. As a mother, Joffe painted multiple intimate images of her daughter, herself, and the two of them together.

Joffe's extensive work requires scaffolding to move the canvas as she uses broad brushstrokes or drips to create drama. The Squid and the Whale (10.2.17) depicts an image of two people sitting on the bed; Joffe in the foreground only wears a pair of pants displaying the broad expanse of her pale back and undersized head. Her daughter Esme sits erectly, wearing a blue dress with stripes. The room has moving focal points with the green pillow, the patterned underwear, and the pink blanket. The two have conflicting emotions; what issues do the mother and daughter discuss? Joffe described the image as the pain a mother begins to experience as the child matures and the mother has to let go. Esme in a Yellow Dress (10.2.18) is an image of Joffe's young daughter. She sits at the table, perhaps doing her homework as she stares outward at the viewer. Maybe the viewer is her mother, and Esme looks like a girl who does not want to sit here. Joffe's broad brushstrokes are evident in this painting, with the face more detailed than the rest of the work. The yellow shirt with the black and red stripes of the chair back holds the viewers' attention on the girl's face—the rest of the painting in a muted palette.

Poppy, Esme, Oleanna, Gracie, and Kate (10.2.19) is a painting of her daughter Esme and her friends. In her light blue shirt, Esme is the only one looking at the viewer as though showing off the people who are her friends. The girls are casually dressed, including Joffe's usual stripes. The minimal background has only two colors; the girls' clothing and faces create movement across the painting. The camaraderie of the girls was evident on their faces. Joffe said, "They'd just had the ears pierced, her and her friend. So it felt like a very definitive moment, funnily, all about power relations and girls. They also look so grown up suddenly. The lollipop looks like a cigarette."[6]

This video is presented in association with the exhibition The Artist’s Mother: Lucie and Daryll.

Claire Tabouret

Claire Tabouret (1981-) was born in France and attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. She moved to Los Angeles to live and work, finding California a dynamic and challenging location. Tabouret's art was inspired by the passing of time and how time changed human relationships. She examines childhood and the events influencing a person's development or how a person acts alone or in a group. Tabouret uses loose brushstrokes, which became animated because she added water. Sometimes she uses a palette of natural tones and other synthetic hues of artificial ingredients. The flow of the paint develops transparency and opacity in her works. Sometimes the faces of the children or women are covered or disguised, their mute faces staring out at the viewer.

L'Affront (10.2.20) portrays rows of children. Tabouret uses old photographs; the children posed as though frozen in time. The troupe of boys are dressed in school attire, their shirts tucked in and ties knotted in place. Each of the boys maintains their personality, some looking defiantly, others hesitating to step into life. The tonalities of color are dark in color and theme; a fluorescent base layer establishes a moody environment. The landscape in the background presented a scary image; the children's future was also blurry and unknown, sometimes intimidating. Les Sorciéres (The Witches) (10.2.21) is also based on a found photograph, each child bringing their future. The children are of different ages, the younger ones in the front row. The older the child, the more their face appears like a mask, having learned to hide their feelings. The girl wears Tabouret's signature fluorescent green in the middle of the first row, centering the painting. Each girl has long, straight hair without variation; the mold young girls are forced to accept, and few of them rebels. One girl in the middle of the back row is wearing a bright scarf, and a few girls have bows in their hair, small tributes to walking their path. Tabouret used her light wash of very dark gray to define the ominous-looking environment.

Michelle Gregor

Michelle Gregor (1960-) was born in San Francisco and raised in Tahoe City by parents who believed in the academic exploration of the arts. Gregor was awarded a BFA from the University of Santa Cruz and an MFA in ceramics from San Francisco State University. She is a sculptor and painter working in the late-twentieth and early twenty-first-century continuum of the Bay Area Figurative Movement, continuing the legacies of artists Manuel Neri and Nathan Olivera. Well known for her abstracted figures, Gregor uses a complex layer of underglazes and glazes on her solid clay pieces. She slices them open after forming the clay and hollows them out before multiple firings. Gregor's feminist and queer identities manifest in the dignity and strength of her partially abstracted female figures. Perhaps most known for her mastery of color, she fires multiple successive layers of stains to achieve complex layers of nuanced surfaces.

In Blue Figure (10.2.22), a seated figure with her hands behind the figure tilts her head slightly down, looking at the ground. The complex layers of glazes are finished in cobalt blue with orange in specific places like the hands, hair, and lines. The close-up (10.2.23) shows the figure's abstracted face with small, pursed lips, a short flat nose, and closed eyes. The different brush marks, sgraffito, layered stains, and glazes contribute to a nuanced and painterly surface. Areas of bright color exist alongside raw clay.

Art is a spiritual necessity. The creative spirit is the best a human being can reach for. It connects us to people in the present, the past, and the future—Gregor

Bari (10.2.24) expresses implied movement seen in the forward-leaning angle of this sculpture. Several marks are purposely left by the tools used to sculpt and shape the surface to create areas where slips and glazes collect and pool, creating texture. The analogous color palette unifies the form. Corinth (10.2.25) is a fragmented seated figure on a rectangular base and exemplifies the nuanced and lush surfaces that Gregor is known for in her ceramic figures. Areas of gloss contrast with matte, and marks from sculpture tools and brushes catch the color to create a varied texture. Using water as a medium, color is applied, and gravity pulls and pools to follow the contour of the form. The figure also demonstrates Gregor's oversized bottom half of a figure. The top half is delicate, and the bottom half is large, the two parts of the figure in conflict.

From the Figure and Ground series, Gregor unconventionally uses ceramic kiln shelves in the artwork, By The Shore (10.2.26). This wall-hung work has both painterly and sculptural elements with pooled glazes. The abstract marks and brilliant coloration coalesce within the composition. Gregor's painterly approach is evident here in areas of bright color, emphasizing the head and knee of this figure. The multi-colored background, focusing on bright red, is balanced by the black block in the lower part of the background, bringing the figures' view to the hand down to the base. The black color is repeated in the base.

Mendocino Art Center’s Artists Speak Video Series featuring sculptor Michelle Gregor.

Chiho Aoshima

Chiho Aoshima (1974-) positions her figures in a more haunting landscape, balancing the whimsical and the more surreal fantasy. She was born in Tokyo and studied economics at Hosei University. Aoshima did not find the subject exciting, and after she learned about Adobe Illustrator and graduated from the university, she abandoned economics to pursue art. Aoshima said about her art, "My work feels like strands of my thoughts that have flown around the universe before coming back to materialize."[7] Her work incorporates spirits believed to exist in the universe and includes them in creating the relationships between nature and humans while visualizing alternative realities.

Aoshima's work is based on traditional Japanese painting while using modern technology to create her art. Her work is flat with a single plane of depth. She uses digital drawing tools to design the images and reproduces them on immense digital prints, a more simplified manga-looking image. The results often resemble surreal dreamscapes with colorful and cartoon-like images, although the figures usually are in the middle of a dark, disturbing landscape.

Aoshima is part of the Kaikai Kiki artist group run by Takashi Murakami. Kaikai Kiki means powerful and sensitive, two yin-yang forces. The group is collaborative and follows the ideas of the Superflat imagery found in manga style. The artists in the group use new digital technologies to create and produce their work. Aoshima does her design work in Adobe Illustrator to develop futuristic sci-fi imagery. Her work is easy to replicate in new technological printing processes. The way the group works is similar to the ukiyo-e art from the past. Ukiyo-e was also made in a workshop with a talented, skilled leader who taught younger artists.

The Divine Gas (10.2.27) portrays only part of the complete mural of an enormous young girl lying in a verdant landscape. Around her are butterflies and deer and other images producing an idyllic place. Storm clouds and the storm genie gather in the sky. Some figures tumble to the ground, while others still wait in the clouds for their eventual fate. Aoshima has created a fantastical daydream. The installed mural in Boston's Institute of Contemporary Art was 12.8 meters long. When the mural was removed for another installation, Aoshima required the museum to cut the image into small squares no bigger than 10 x 10 centimeters. She had the museum send her photos of the destroyed image to ensure the destruction was completed correctly and small pieces could not become a souvenir.

Some of Aoshima's work may be seen as catastrophic scenes where nature rages and humans are battered. She uses conflicting colors to create emotion and demonstrate the power of nature. Magma Spirit Explodes (10.2.28) and Tsunami is Dreadful (10.2.29) portray the human mind's perception of nature's wrath. The 12-meter mural has two parts, one fiery destruction and the other, the giant wave of a tsunami tidal wave. On the Magma Spirit side, she used a candy-colored young girl spitting out the magma while looking at the mirror, reflecting her more ghostly-like face. Conversely, the brilliant blues wave crashes onto the Magna-filled land like two warring factions. The mural's long horizontal design is reminiscent of past Japanese handscroll paintings, unfolding the apocalyptic image across the scene.

Jylian Gustlin

Jylian Gustlin (1960-) is a San Francisco Bay Area painter in a contemporary redefinition of the 1960s-70s San Francisco Bay Area Figurative artists, their styles, and techniques. She studied mathematics and computer science at San Jose State University and received a BFA from the Art Academy of San Francisco, where technology emerged as an art medium. Gustlin's vibrant paintings explore the impact of new technologies on perception: though she uses traditional painterly techniques. Inspired by a lifelong love of the San Francisco Bay Area, Figurative artists, mathematical theories such as the Fibonacci sequence, the resonant tones of Latin phrases, African masks, and antique Roman vessels, Gustlin's work is genuinely a modern hybrid between the past and the present.

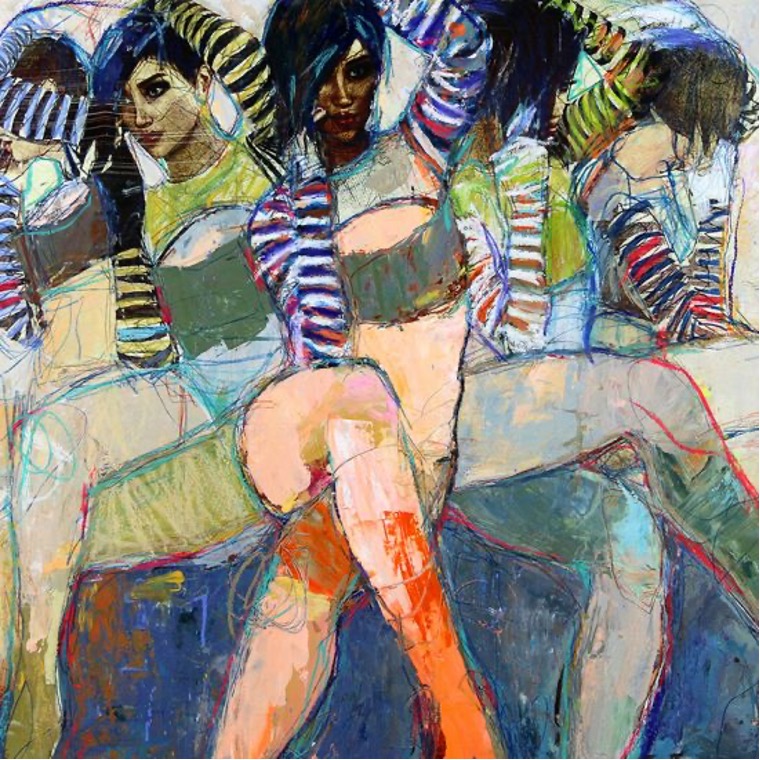

In Gustlin's paintings, the human body emerges from the background and moves through our emotions. The rich patterns of shapes and colors bring the figures to life and challenge our imagination. Interwoven color is the beauty and explosive atmosphere Gustlin brings to the human body. The moody yet qualitative emotions are expressed in her paintings as they emerge into the foreground, bringing the complex, layered textures of the figure into our space as we feel its presence and feelings. The figures become vibrant mixes of color and texture to transcend race, ethnicity, and even evolutionary life form. Sirens 8 (10.2.30) brings five women, individually similar yet different. The stripes on their sleeves form motion, their crossed legs anchoring each person to the seating. The emotions portrayed by each person are hidden in their faces.

Illustris 36 (10.2.31) and Illustris 25 (10.2.32) represent ethereal forms, one of a kind, the perfect body. Yet, the figures are deep in thought, contemplating the world and life's meaning. Each figure is positioned to give the viewer their emotional interpretation of the image. Gustlin uses many colors on her figures, blurring racial lines. The figures are seated on interpretive lines as dark colors anchor the bottom of both images.

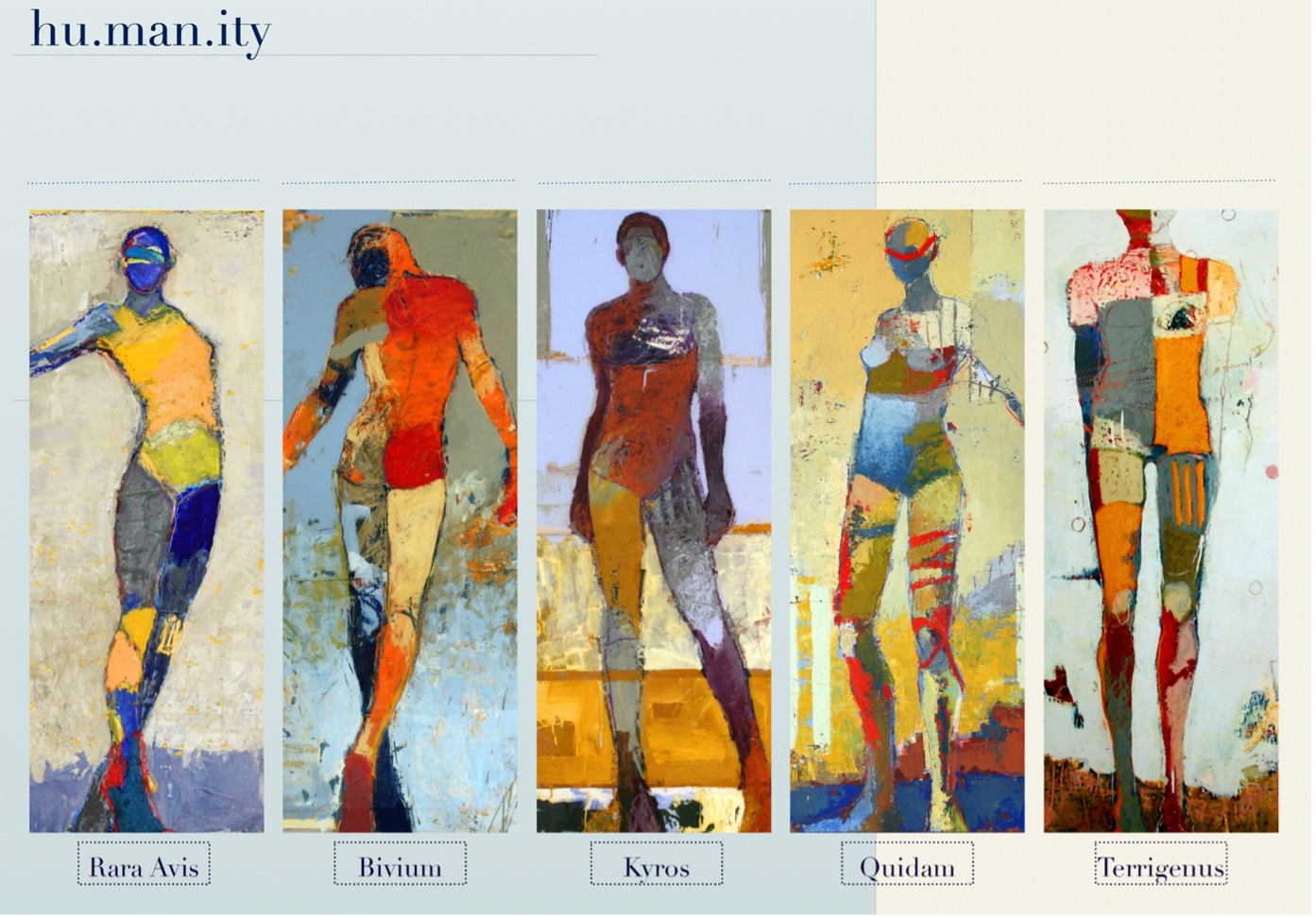

Civil rights and feminist movements in the last 100 years have created a new focus and concepts, opening up the world of art to women. In the 1960s, women's liberation movements were standing up for women's rights, and this is where the beginning of Jylian's life started, to fight for political and civil liberties at protests. New generations of artists responded to the civil rights and women's movements, demanding inclusion in the art world, though it was considered an exclusively white male pantheon. Hu.man.City (10.2.33) is the response to the current state of the world and how we are all the same regardless of how we look. Each figure is from her earlier figurative series; Rara Avis, Bivium, Kyros, Quidam, and Terrigenus. The figures are unique unto themselves while still part of the common humanity. Gustlin's use of color defines the figures as members of any race or country, creating the uniqueness of every person.

This is a video of my artwork over the decades. I thought it would be an excellent virtual gallery experience. I hope you enjoy it.

Hollis Chatelain

Hollis Chatelain (1957-) is an American quilt artist who graduated with a BA from Drexel University. Chatelain specializes in textile painting and quilting. She lived in West Africa for 12 years working for humanitarian organizations. Her experiences caused her to reflect on challenging social and environmental themes. Chatelain's style was based on dream-like colors and imagery. The untold multicultural stories of people and the earth are depicted in her dye-painted scenes. Her work has been described as "easy to gaze at, but hard to forget." From dreams to reality, Chatelain often starts with a monochromatic vision. From there, she researches and looks for images describing what she dreamed. The colors, faces, and plants must authentically be what they could or should be. Chatelain has realized that her dreams often give insight into places and people she has never seen.

Just as my many colors of thread hold the layers of fabric and batting together, I feel my creations can also pull people together. We are wrapped in cloth from birth through death. Thus, fabric creates a connection that suits the issues I address in a personal way. I choose to work in larger-than-life sizes so that when a piece is finally finished, viewers will be called from all distances to come closer and step into the story—Hollis Chatelain

Once the research is finished, she draws, using photos as inspiration. Often working from 30-40 photos, Chatelain will sketch many small thumbnails and then enlarge the small drawings onto large paper the size of the piece, creating the basic design. After transferring the design to fabric, she paints using fiber-reactive Procion dyes. The dyes are usually six values of one color (the color of the dream). Once the painting is finished, the dye is washed, and batting is added to prepare it for quilting. Chatelain often uses over 200 colors and over 20,000 meters of thread in one piece, adding contour, depth, and volume to her quilts. Chatelain creates textile paintings because she loves the tactile quality of the fabric, combining her love of photography, drawing, and painting. Viewers can see the detail and meaning of the pictures and the diversity of thread colors, creating intense images.

African American women could not legally vote in every state until The Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965. Dreams Realized (10.2.34) portrays women who are a force to be reckoned with in their communities across America. During elections, the women unite neighborhoods and take them to the polls to vote. The white fabric was painted with multiple shades of blue. The three red, white, and blue "I Voted" stickers stand out, demonstrating that every vote counts.

In February 2002, Chatelain dreamed of Hope For Our World (10.2.35). The dream was in purple, and Archbishop Tutu stood in a field surrounded by children worldwide. Desmond Tutu represents hope for world peace and the future of children. The quilt was painted with thickened fiber reactive dyes using six values of purple dye on cotton fabric. Chatelain incorporated transparent white doves throughout the quilt, the doves as a symbol of peace.

In the spring of 2000, Chatelain created a yellow piece about the continual droughts threatening many places on our planet. Fresh water is precious and limited. It is a worldwide problem, so the images represent four different continents. The farmer looks at the shriveled corn, a woman needing water to wash her food, the young boy drinking scarce water, and the kangaroo seeking water are all part of the intricate, overlapping scene. Precious Water (10.2.36) is painted with dyes using six values of yellow, then quilted with over 200 different colors of thread.

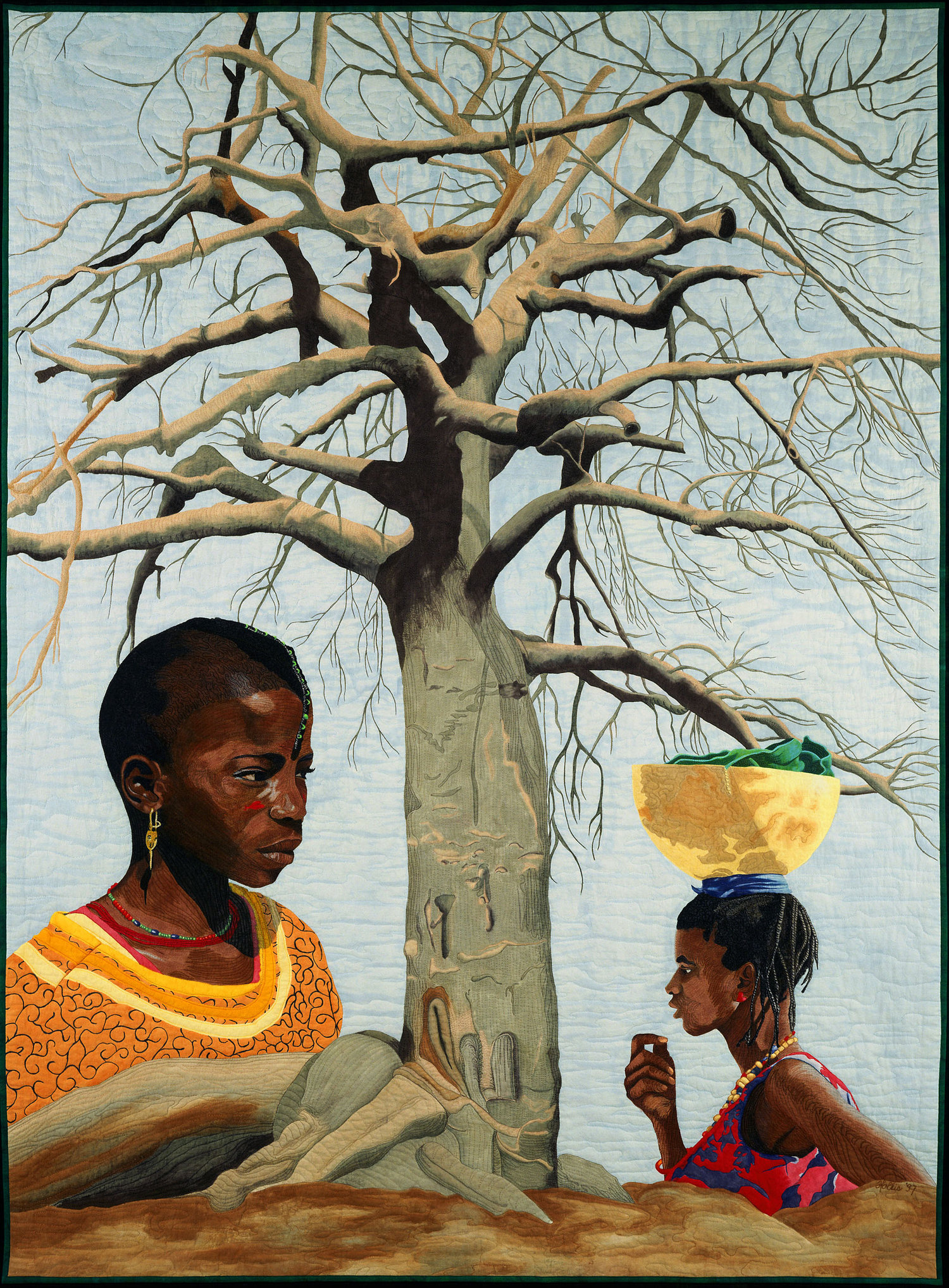

The Sahel region is just south of the Sahara Desert, with scarce trees. One type of tree that grows in this region is the baobab tree, also called the "tree of life" because it provides food, medicine, and shade for the people there. The Fulani people shown in the Sahel (10.2.37) are nomads and dependent on the food they can find, including the baobab tree. The tree is the center of the image and is painted in warm colors with a thick trunk and delicate small branches. The light blue colors of the sky bring a contrasting background to the tree.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (1977-) was born in London; her parents were emigrants from Ghana. She received a bachelor's degree from Falmouth College of Art and a master's from the Royal Academy Schools. During graduate school, Yiadom-Boakye developed her concepts of focusing on just the figure and not building a narrative into the portrait. About her artwork Yiadom-Boakye said, I think less about the figure than I do about how they are painted. I ceased to see the paintings as portraits a long time ago."[8] Yiadom-Boakye's portraits are of imaginary people; she paints with muted colors and a dark palette. She explains, "In the beginning, it's this building up of tone and color, and laying the foundations of something, and gradually sharpening and sharpening and sharpening."[9] Her Black figures are only suggestions of real people she creates with color, light, and brushwork. Yiadom-Boakye paints quickly, only needing a few days for each painting. She uses herringbone linen and occasionally canvas with a loose brushwork style to paint the fictional characters. The images of people come from her collection of scrapbooks or drawings. Usually, the characters are alone and generally have their eyes averted as though lost in thought. Yiadom-Boakye portrays her Black men and women in commonplace domestic locations with ordinary clothing.

In Pale for the Rapture (10.2.38), the figures are independent and sit on different sofas. Yiadom-Boakye gave each figure a colorful background, a deviation from her usual, simple background. One sofa has a yellow and red striped plush covering, and the other has a vibrant black and white diamond covering. The well-dressed figures are relaxed and contemplative, each with their legs crossed. She builds multiple emotions into the figure; are they tired, worried, bored, or just waiting? Yiadom-Boakye could place the figures and give them expressions to exist in multiple settings, ordinary people. Yiadom-Boakye says her figures have "a general idea of normality. This is a political gesture for me. We're used to looking at portraits of white people in paintings."[10]

Yiadom-Boakye was often inspired by the work of nineteenth-century artists like Degas. Using the ballet dancer, almost exclusively portrayed as white dancers, she painted The Host Over a Barrel (10.2.39) of three Black girls. The girls have their hands on their hips, waiting for the next move. Yiadom-Boakye is a master of using the background to highlight the dark skin of the girls by adding a glimmer of light to outline the figures. The girls' dark clothing and lighter skin make a quiet interlude appear. The highly polished ballet floor beautifully reflects the girls' legs as they stand. Yiadom-Boakye used the same technique of using a shimmering light to outline the reflections. She generally made dark backgrounds to enhance the lighter complexions and highlighted skin regions. Usually, this technique was thought to be unsuitable for black models according to Western painting practice. However, Yiadom-Boakye has developed perfect techniques to portray her Black figures.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2020/02/07/80277...tour-next-year

[2] Retrieved from https://www.phillips.com/detail/amy-...ald/NY010720/1

[3] Retrieved from https://brooklynrail.org/2016/07/art...-eisenman-2016

[4] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collec.../search/830456

[5] Retrieved from https://www.pamm.org/collections/you...e-us-away-2005

[6] Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-44353961

[7] Retrieved from https://www.artnet.com/artists/chiho...hima/biography

[8] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/artists/46962

[9] Retrieved from https://jsma.uoregon.edu/sites/jsma1...dom-Boakye.pdf

[10] Retrieved from https://www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr...or-the-rapture