9.5: Young British Artists Chapter (1980s – 2000)

- Page ID

- 209048

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

In 1988, a group of young artists in Britain held two pop-up exhibits, Freeze in 1988 and Sensation in 1997. The art differed from the traditional, as artists used unusual materials and sometimes shocking images. The art was distinctive and almost notorious, and the artists earned the name Young British Artists (YBA). The negative coverage by the English press gained them publicity. Many artists attended or graduated from Goldsmiths College of Art in London. The school helped develop the movement and cultivated new art forms by abolishing the typical separation of painting, printmaking, sculpture, or other art methods. They encouraged students to combine concepts for new themes in mixed studios and be more entrepreneurial in marketing and showing artwork.

Stylistically, the artists used ideas from Minimalism and Conceptualism; however, they frequently incorporated the darker properties of modern life. Each artist developed a different approach. Some artists used found materials; others employed video, film, printmaking, paint, or photography, and others fashioned extensive installations. The Young British Artists have used appropriated objects, dead animals, furniture from their house, food, cement blocks, cigarettes, or other material. They had to follow no limits or parameters; the artists were open to developing a process and selecting objects that may be shocking or challenging. The artists created a reputation for doing whatever they wanted with whatever material they chose, which was not always an acceptable idea to many in the art world.

Most artists were in their twenties and recognized the opportunity to bring change to the stagnant English art market, each with different ideas. The Tate Modern Gallery was also part of the sensational acceptance of the new art forms. London had no modern art public museum, and private donors supported the funds to acquire contemporary modern art and build a gallery. The Young British Artists were a significant part of the move to modernity. Although female artists were in the minority, they played an essential role in changing attitudes, disrupting the concepts of female art. They changed the acceptable images of women in art and used materials generally outside the scope of female art. Artists like Jenny Saville were affected by institutional patriarchy and the control of written history by male ideas. She began to paint her female nudes outside the norm of perfection and into the depiction of reality. Saville and others disrupted the concept of beauty and acceptability and brought significant change to the ideas of female artists. Artists in this section:

- Tracey Emin (1963-)

- Sarah Lucas (1962-)

- Anya Gallaccio (1963-)

- Jenny Saville (1970-)

- Rachel Whiteread (1963-)

- Angela Bulloch (1966-)

- Fiona Banner (1966-)

Tracey Emin

Tracey Emin (1963-) was born in London. Her father was a Turkish Cypriot, and her mother from Romanian descent. She studied fashion design and printing at different colleges before receiving a master's degree in painting from the Royal College of Art. Unfortunately, Emin was raped when she was only thirteen, something she said was all too familiar in her neighborhood. The tragedy significantly influenced her work; she is known for her autobiographical and confessional art style. Emin works in multiple media types: sculpture, film, painting, photography, etc. One of her first significant exhibitions was about her bed, bringing her major recognition.

For her installation of My Bed (9.5.1), Emin took the bed from her room, along with all the detritus surrounding it, and installed it in the gallery. Emin stated the space accurately reconstructed her room after she became depressed. She spent weeks in bed drinking, smoking, having sexual relationships, or eating to deal with her emotional distress. Strewn around the bed, Emin included used condoms, dirty underwear, stained sheets, old Kleenex, and cigarette butts.[1] She termed this confessional art, revealing potentially embarrassing parts of her life. The press and critics were in an uproar declaring the installation was not art. Others thought of the bed as a definition of the boundaries of a young woman.

Tracey Emin’s My Bed returned to Tate Britain fifteen years after the work saw her nominated for the Turner Prize. It was displayed alongside paintings by Francis Bacon and Emin’s more recent drawings, creating a more immersive environment to experience the piece up close.

Psycho Slut (9.5.2) was made on a blanket. Emin appliqued different words and phrases on patches of text she wrote by hand. The blanket became a history of Emin's life in intimate detail. She inscribed her childhood abuse and the pain of an abortion. Emin made other blankets from fabrics she felt brought her comfort, including her clothing, the clothes of her parents, and other scraps found around the house. Emin made multiple digital neon art of her poetic thoughts. She wrote about the tensions of relationships and how the interdependencies affect a person's vulnerability or feelings of empowerment. Fantastic to Feel Beautiful Again (9.5.3) demonstrates her recovery from a poor relationship. All her sayings reflected her open feelings, sometimes playful or other times confrontational and constantly thought-provoking.

Sarah Lucas

Sarah Lucas (1962-) was one of the later members of the Young British Artists recognized in the 1990s for her extraordinary subject matter. Her work was sexual and blurred masculinity and femininity; Lucas declared she liked androgyny. She was born in London and studied art at different colleges before graduating from Goldsmiths College with her degree in Fine Art. Lucas' work was part of the early Freeze exhibition and was considered one of the more shocking members of the group. She experimented with materials and images, including making a toilet with cigarettes. Lucas used found materials she manipulated and altered. She applied some odder materials like fruit or vegetables to portray body parts. Lucas' work was based on everyday objects to depict her exploration of sexual ambiguity and how something familiar or strange brings a disorienting tension.

Lucas stuffed nylon stockings to form the soldier's body in her sculpture, Oh! Soldier (9.5.4). Old used suspenders form the top of the body, and the legs are set in army boots she cast from concrete. Two coat hangers help hold the shapes in place. Automatically, the soldier is perceived to be a male, a reaction to the title of the work and the heavy boots. However, the body is made from tights worn by women, making this sculpture open for sexual interpretation. Titti Doris (9.5.5) is made from tights stuffed with fluff and slumped in a chair. The figure demonstrates and focuses on the objectification of female breasts, a cluster of saggy shapes mounded like a pile of melons—each oversized shape announcing its right to exist.

Sarah Lucas speaks about her exhibition at San Francisco's Legion of Honor, where her pointed, provocative work is presented in dialogue with the sculptures of Auguste Rodin.

Anya Gallaccio

Anya Gallaccio (1963-) was born in Scotland, where her father was a TV producer and her mother an actress. Gallaccio attended Goldsmiths College and was part of the Young British Artists Freeze exhibition. She created installations based on organic materials that transform and decay into unpredictable artwork. Because she uses objects like flowers, ice, sugar, trees, or other natural material, the materials may smell good or be exceptionally colorful when first established. The elements may melt, wilt, collapse, or decay from their biological processes as time passes. Gallaccio referred to her artwork as a performance because the activity occurred slowly. One of her installations included assembling a ton of oranges over the floor and watching the natural progression of decay, the performance of nature interacting with the oranges.

In her installation, The Light Pours Out of Me (9.5.6), Gallaccio said, "I would like it to be unsettling for people when they first encounter it. I'd like them to question whether they should enter the gate or not. Then, when they come into the space, it is very formal, quite grandiose but intimate, a quiet place for one or two people."[2]Gallaccio wanted viewers to see the artwork personally and up close. She created grottos like those found in older English landscapes. The walls (9.5.7) ripple with amethyst and groups of crystals, all appearing smooth yet dangerously jagged. At the bottom lays a small pool of water (9.5.8) from black obsidian stone. The installation changes by season, rainfall, vegetation growth, or even as people remove small pieces of stone. Gallaccio imagined the installation would change over geological time instead of human time.

Gallaccio's installation of Red on Green (9.5.9) comprised 10,000 red roses, laid like a carpet across the gallery floor. Initially, the roses were bright red and soft and emitted the voluptuous aroma of roses. However, the thorns were still on the stems, and it was dangerous to carelessly walk across the floor or pick a handful of blooms. The roses began to decay relatively quickly (9.5.10) until they turned moldy and dark. The roses transform from beauty and romance to ugly and decayed.

Anya Gallacio creates site-specific installations from organic materials to convey the nature of change.

Jenny Saville

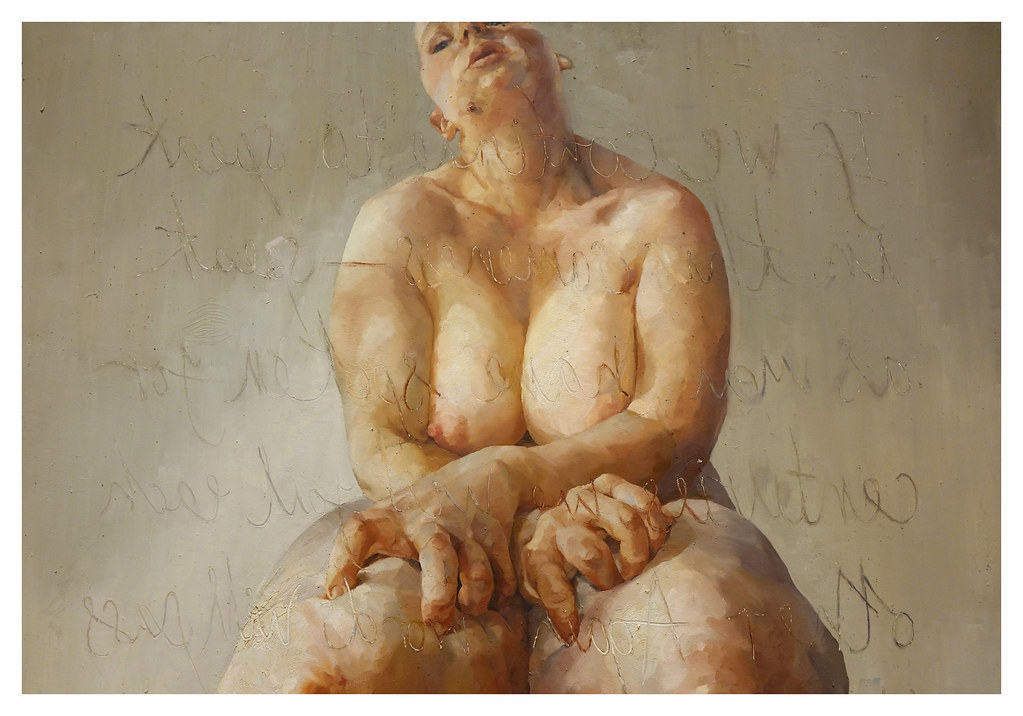

Born in England, Jenny Saville (1970-) received a degree from the Glasgow School of Art and went to the United States to study at the University of Cincinnati. Saville took a women's study class at the university and was exposed to different political and feminist views. While in Ohio, she observed, "You saw lots of big women. Big white flesh in shorts and T-shirts, all of whom had the physicality that I was interested in."[3] Saville also went to New York and watched a plastic surgeon work, helping her understand the anatomical shapes and formations of extreme human bodies. The images and her studies influenced Saville's unashamedly feminist artwork of large or obese women. Her first show in England was successful, and the gallery began to show her work with other Young British Artists. Saville's paintings were larger than life-sized, and the skin was highly marked and distorted. Her paintings illustrate the voluminous body, unable to hide the distorted proportions. Propped (9.5.11) was an early image of the oversized nude woman with her head tossed backward. Her eyes are closed as her hands claw her large thighs as though her thoughts are painful. The woman appears to be repulsed by her image, hiding from the disdain of the male gaze. Saville applied the paint in thick layers, becoming visceral flesh and generating an emotional response.

Saville was a master of the constructs of the body. She demonstrates how flesh flows and rolls upon itself and how excess skin drapes and causes different shadows. Saville paints the body as a complete entity and how its stretches in one place and falls in another. In Strategy (9.5.12), Saville depicts the same women in different positions. She painted the person as viewed from the ground exaggerating the size of her thighs and stomach, the upward angle in the massive painting dwarfing the viewer. The dimpled flesh has overtones of gray, portraying the flesh as sickly and bruised. The image is not the idealized person and views generally expected in paintings; instead, the viewer is uncomfortable with the images because it does not meet the standard, flawless feminine body. Saville also painted a series of large-scale works portraying heads. Rosetta II (9.5.13) and Bleach (9.5.14) are two of the paintings in the series. Both images demand the viewer's gaze, unable to look away. The women do not have the smooth, silky skin seen in advertisements, movies, or other media. They carry the marks and scars obtained over years of society's subjective actions against women. The woman in Rosetta II is blind; her eyes are seemingly like globes, and her head is positioned like many religious images of suffering. Bleach looks directly at the viewer, her mouth swollen on the marked face. Saville was interested in how image-conscious people in the country were, these women not meeting the proper image of the plastic surgery population.

Jenny Saville is a hugely successful international artist best known for her monumental depictions of the naked female form. Saville draws upon a wide range of sources in her work, including medical and forensic textbooks, children's drawings, graffiti and online images, and celebrated paintings and drawings of the past.

Rachel Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread (1963-) was born in Essex, England; her mother was an artist, and her father a teacher. Her first art education was at Cyprus College of Art, followed by the Slade School of Art, where she studied sculpture. Whiteread was part of the Young British Artists' second show, Sensation. Most of her works are based on ordinary objects she casts. Whiteread is known to make a cast of an existing chair or table, interested in the line and form the object creates. She constructs sculptures from small elements to entirely cast buildings. One of Whiteread's most famous works is the inside of a Victorian house cast in concrete. The cast objects become a replica of the original, forming ghostly representations. One of her major outdoor works is the Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial (9.5.15) in Vienna, a memorial for the 65,000 Austrians murdered in the Holocaust under the Nazi regime in World War II. On the outside, each row is a set of nameless books representing the people. The pages of the books face outwards, the spines of the book are inwards, and the identity of the titles is unknown. The doors on the front are permanently closed and inside out without handles portraying the finality of the massacred people. Incised on the broad concrete base are the names of the different concentration death camps where the people were sent for execution. There was some controversy about the monument's appearance because it was not beautiful. At the unveiling, Simon Wiesenthal stated, "This monument shouldn't be beautiful; it must hurt."[4]

Embankment (9.5.16) was constructed from 14,000 translucent, white polyethylene boxes stacked in multiple formations. Some think they might be icebergs, with others believe they are stacked sugar cube villages. Whiteread became fascinated with boxes while cleaning out her mother's belongings. She filled different boxes with plaster for the installation and then stripped the actual box off, leaving the cast plaster box. Each box was unique, with scars, torn sections, or even staples; all the blemishes showed in the plaster and remained. Next, she re-made the boxes with translucent polyethylene, a process she followed for thousands of boxes. The actual installation projected different and unusual feelings of space and scale. Some of the box stacks were exceptionally high, a dizzying view; other stacks allowed the viewer to touch them. Whiteread was also known for her casts of furniture. Untitled (100 Spaces) (9.5.17) is an exhibition composed of 100 resin casts of the undersides of different chairs. They are arranged in twenty rows, with five objects in each row. The pieces form a grid, the colors translucent. Art critic Craig Berry stated, "The sculpture oscillates between abstraction and reference. It shifts from an accumulation of mute cubic forms to a shimmering index of everyday life."[5]

Tate Curator, Linsey Young, explores the work of Rachel Whiteread, one of Britain’s leading contemporary artists and the first woman to win the Turner Prize in 1993. Using industrial materials such as plaster, concrete, resin, rubber, and metal to cast everyday objects and architectural space, her evocative sculptures range from the intimate to the monumental.

Angela Bulloch

Although Angela Bulloch (1966-) was born in Canada, she attended Goldsmiths' College in London as part of the Young British Artists. Bulloch found an association with the group helpful as a young adult. Whenever her work was mentioned, the YBA label was attached, which was good publicity. Bulloch received multiple awards and prizes from different countries for her early career. She was fascinated with mathematics and its boundaries in the world of art. She applied mathematical concepts in her work, especially video, sound, and light. Bullock also incorporated music into her sculptures and installations to enhance the abstract mathematical qualities of movement. Bulloch became known for her "pixel boxes," illuminated boxes displaying millions of colors based on computer programming.

Pacific Rim Around & Sideways Up (9.5.18) is one of Bulloch's pixel box sculptures. The boxes were made from wood, copper, or aluminum with plastic as the front screen. The sculpture presents both a flat two-dimensional view and a three-dimensional look. Different colors, lights, and music brought the installation alive. After creating structures based on her pixel box ideas, Bulloch started a new concept based on astronomy. She explored interplanetary and interstellar relationships. The work was based on gravitational fields and visual representations of planets, stars, and the universe. In Smoke Spheres (9.5.19), Bulloch used different-sized, translucent, smokey-colored spheres. A computer-controlled the lighting and changed continually with different spectrums and intensities of light. An altered Jazz Funk composition based on symphonic music played with various light transformations.

Fiona Banner

Fiona Banner (1966-) was born in England and studied at Kingston University in North West England. She and many of the Young British Artists attended Goldsmiths College of Art. After she received her master's degree, Banner exhibited in her first show. Initially, she was known for printed text or 'wordscapes' or 'still films' made on solid blocks, earning her the nickname, The Vanity Press. She based the texts on many Viet Nam war films as a protest. Banner's art covered different styles, including her work with text, sculpture, and installations.

Don't Look Back (9.5.20) were panels made with black text on silver paper over three panels. The words were from a documentary about Bob Dylan called Don't Look Back. Dylan had just completed a tour of England, and the film was about his music and concerts. When Banner discovered the documentary film was not available to the public on video, she decided to write her narrative about the film. Each panel displays different words, although, from a distance, they all appear the same. One panel emphasizes the song's lyrics, another documents the placards Dylan held, and the third describes some parts of the film. Banner wrote the panels in the first person to give an illusion of a person in attendance, explaining their viewing. She made many different text images recounting other scenes from war films to pornography. Each of the large-scale works reflected her personal view of the scenes unfolding. Banner used various media, including paint, marker pens, pencils, and screen-printing.

Banner's sculptures were frequently oversized, and she created five bold Full Stops (9.5.21) placed throughout the plaza by the London Bridge. The round sculptures were coated with the same shiny black paint used for London taxis. The smooth sheen allowed the surrounding building to reflect off the surface of the sculptures. Each of the five sculptures represents different font types; Slipstream, Optical, Courier, Klang, and Nuptail.[6] Banner said, "If these sculptures are full stops, then we, walking amongst them and the buildings that frame them, become like the missing letters and words of a sentence. Banner gives us in solid form the pause, the silence, the moment we draw breath and reflect."[7]

Banner received a commission to create an installation using two decommissioned airplanes. One plane was a Sea Harrier (9.5.22) jet that flew in the war over Bosnia, and the other was an RAF Jaguar (9.5.23) used in Desert Storm. The Harrier is hung from the ceiling, looking like a trussed-up bird, while the Jaguar has its belly up, resembling a wounded animal. Banner said she was always fascinated with war and planes. As a child, she walked in the hills of Wales with her father, and Harrier jets would come out of nowhere and rip up the sky. She believed, "It was a completely transformative moment, but we were left, literally with words knocked out of us, wondering how something that was such a monster could be so beautiful."[8] Banner used the planes in the exhibit to demonstrate the odd juxtaposition of the beauty of the plane and the destruction they bring. Banner removed the paint from the Jaguar, allowing viewers to see their reflection. The Harrier was painted with feather markings to accent the concept of a trussed bird. The planes also demonstrate the unusual placement of jet planes in a neo-classical gallery.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.theartstory.org/movement...itish-artists/

[2] Retrieved from https://www.jupiterartland.org/art/a...urs-out-of-me/

[3] Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/artandde...igallery.art10

[4] Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/20...6/kateconnolly

[5] Retrieved from https://craigberry93.medium.com/rach...n-135c9482f024

[6] Retrieved from https://atlondonbridge.com/art/full-stops/

[7] Retrieved from https://publicartaroundtheworld.com/...ang-sculpture/

[8] Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/artandde...n-fiona-banner