7.8: Surrealism (1920 – 1950s)

- Page ID

- 135005

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

The Manifesto of Surrealism by André Breton was a publication for a literary movement based on experimenting with writing about the subconscious or dream states, the world of imagination, and irrationality. Early artists experimenting with Surrealism were from multiple countries, creating diverse and symbolic images emerging from the subconscious mind, a place of superior authenticity and the absence of control. Surrealist work was tense and sexual, based on hidden psychological forces in the subconscious. The rational mind was suppressed, and societal controls locked in imagination. They didn't look for art in real everyday life; instead, they used the impulses of the primitive unconscious mind.

Sigmund Freud also influenced Surrealism with his book, The Interpretation of Dreams. He wrote how dreams revealed real human emotion and cravings stemming from the inner mind and its revelation of sex, violence, and longing. Although they embraced Freud, they focused on idiosyncrasy instead of a view of madness. Imagery is the most distinguishable part of Surrealism, often eccentric, weird, or bewildering, meant to make the viewer uncomfortable and challenge their general assumptions of imagery and art. Elements of nature were frequently included in a painting, positioned in strange places, and juxtaposed against an illogical background. Some of the artists supposedly used drugs to connect with their inner minds. In the past, religious beliefs of the mind were instrumental in creating remarkable masterpieces; for Surrealists, the release of the thoughts of the subconscious mind gave rise to this period's great works.

Many painters based their work on political ideals or struggles and revolutionary politics. By the 1930s, with Surrealism embraced by painters worldwide, the movement became a way to redefine ordinary objects into informal organization or meaning, bringing a feeling of alienation, a common position in the modern world. During World War II, many artists came to North America to escape the Nazis and Fascism, bringing their ideas of escapism and dream imagery.

During the 1900s, female artists achieved success; however, risking the tendency to be overshadowed by a male husband or lover. "…for women involved in the Surrealist circle, the situation was even more fraught. The Surrealists were fascinated by women: beautiful women, mad women, young women, or preferably all three conjoined in the ideal figure of the femme-enfant, the child-woman, whose untamed nature might be the conduit to a realm of fantasy and indulgence." [1] Male Surrealist artists generally used females as a symbol of unpredictability. Most of the female artists used different mythical or historical female figures to outmaneuver their imagined conditions, figures with some basis of power, a witch, fairy, crone, pixie, or sprite. Artists in this section:

- Frida Kahlo (1907-1954)

- Remedios Varo Uranga (1908-1963)

- Leonora Carrington (1917-2011)

- Kay Sage (1898-1963)

- Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012)

- Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944)

- Maria Izquierdo (1902-1955)

"Surrealism: The Big Ideas" is a condensed history of the Surrealist Movement, providing a foundation for artists learning to make their own surreal art.

Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was born in Mexico with the name Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón; Kahlo is her father's family name, and Calderón is her maternal last name. She started drawing as a child, although she did not consider an art career. At age six, she contracted polio, causing a permanent limp. In 1922, Kahlo went to the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria to study medicine at the prestigious school. Unfortunately, a bus collision left her with multiple broken bones and internal injuries when she was eighteen, leaving her with life-long pain. Her recovery was extensive, and Kahlo started painting as she lay in bed. After the disastrous accident, she was in a body cast, bound to the bed. Kahlo's mother hung a mirror above her four-poster bed while Kahlo recovered, and her reflection became the main subject of her art throughout her life. Ultimately, Kahlo used her art to help her heal while she spent countless days alone in bed. Afterward, she was forced to wear orthopedic corsets and endured multiple spinal surgeries and many miscarriages. All her pain was reflected in her artwork.

Kahlo grew up during the Mexican Revolution, inspiring her future political fervor. She met Diego Rivera, twenty years her senior, in 1927 and married him in 1929, accepting his infidelities. Both were active in political revolutionary groups supporting the communists and other protest groups. In the early 1930s, Kahlo and Rivera traveled through Mexico and the United States. Their marriage was turbulent as both had multiple affairs, including Kahlo's young sister's affair with Rivera and Kahlo's open bi-sexuality. They even divorced in 1940 and remarried again. Her health was always a problem and deteriorated in the late 1940s, finally dying as she slept in 1954, only 47 years old. Kahlo struggled to be Diego's perfect Mexican wife, which clashed with her multicultural upbringing. One of Kahlo's most celebrated works, The Two Fridas (7.8.1), illustrates this struggle between wearing a traditional tehuana dress and a European Victorian dress. She completed the painting after her divorce from Rivera, with a heart on each person. The heart of traditional Frida was torn and cut, the scissors in her hand, blood dripping on the white dress. Dark clouds fill the background suggesting the turmoil of her feelings.

Kahlo passionately gathered Mexican folk art, especially toys, adorned ceramics, colorful textiles, and religious images, influencing her artwork. Her work reflected the art of Mexico, especially folk art and historical images from the pre-Columbian and Aztec societies, conquering Mexico's culture and revolutionary times and incorporating the culture of Mexico over time. Kahlo's work developed into mainly self-portraits or images of her friends, all based on her extraordinary imagination. She was often immobilized in a cast and forced to paint as she lay in bed. She even attended her first exhibition, transported by ambulance and lying in a four-poster bed the gallery set up for her, disregarding her doctor's orders. Kahlo's work frequently incorporated her physical or psychological pain and the iconography of historical Mexican images. Kahlo also integrated motifs from nature, mainly foliage from local flora and animals, adding a more realistic and organic look to her Surrealistic images. She wore elaborate clothing designed in the style of early Mexican costumes, clothing seen in her paintings. Her pain and agony were also visible in her work, her face contorted into a mask-like appearance, eyes staring as internal organs spilled out from her body. She did not like to say she was associated with any movement, only declaring she was a Surrealist based on her reality, not dreams. Although some of the irrational impulses of Surrealist artists are visible in her work, Kahlo opens her own life and herself as the main subject and concern in her work. She stated, "They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn't. I never painted dreams. I painted my reality." [2]

Frida Kahlo is the most famous female artist in history. She deviated from the traditional portrayal of female beauty in art, and instead chose to paint raw and honest experiences. A near fatal bus accident at 18 left Frida crippled and in chronic pain her whole life, but she managed to make a virtue out of adversity, and astonishing original art out of her pain. She was a Mexican, female artist who was disabled, in a male-dominated environment in post-revolutionary Mexico. A feminist icon who broke all social conventions, and produced some of the most haunting and visionary images of the 20th century.

Many cultures used monkeys as a cultural symbol, usually associated with lascivious and defined as lust, a primal image of a man in Mexico. However, Kahlo owned a pet spider monkey, incorporating it into her work, portraying the monkey as a protective symbol, an animal with its personality and soul. In Self Portrait with Monkeys (7.8.2), the monkeys encircle her, seemingly shielding her from those outside the painting. Kahlo started as a teacher at an art school in Mexico City when her injuries worsened, and she had to teach at her home, her class drifting away to only four students who stayed with her. Many believe she incorporated the four monkeys in this painting to honor those four students. The background is decorated with leaves, a typical adornment in her work, and a bird of paradise, a flower commonly found in Mexico. Kahlo said, "I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone because I am the person I know best." [3]

Most of Kahlo's paintings included elements of pain and suffering, a continual part of her life as she had several surgeries for her back and wore different rigid corsets for support. The Broken Column (7.8.3) is reminiscent of her hospitalization, her back broken, and her agony and horrific pain evident in the painting. She used a metal column to represent her broken spine; the column fractured in multiple places and was seemingly ready to collapse. Her body was held together with a surgical brace as nails punctured her face and body. Her lower body is covered with a cloth resembling a hospital sheet. Despite the pain, she looks forward to a triumph over her situation. The image also demonstrates her as a young, still viable woman displaying the nude sections of her upper body. To create the painting, she used firm brushstrokes and well-defined colors.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=720&height=929)

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=744&height=775)

Kahlo started Portrait as a Tehuana (7.8.4) in 1940 after she divorced Diego Rivera after ten years of marriage and was unwilling to tolerate his affairs any longer. She painted an image of Rivera on her forehead, giving the self-portrait the alternative names of Diego in My Thoughts and Thinking of Diego, demonstrating her continued love for him. For the self-portrait, she wore the clothing worn by the Tehuantepec women. On her head are leaves with roots similar to a spider's web, perhaps trying to entrap her feelings about Rivera. As with other self-portraits, she maintains the bold, self-assured image, staring forward, her dark eyebrows highlighting the directness of her eyes. Kahlo frequently wore the clothing of the Tehuana women, a pre-Hispanic people where women realized equality with their male counterparts; women also had strength and sensuality. Kahlo looks directly at the viewer in Self Portrait with Necklace of Thorns (7.8.5). A thorn necklace smothers her throat and chest with the black love charm hummingbird, a pendant dangling from the thorns. However, this hummingbird is dead instead of lively and colorful. The monkey on her shoulder tugs at the necklace; the thorns draw blood. Because Rivera gave a monkey to Kahlo, some historians view the monkey as a symbol of Rivera inflicting pain with the thorns. The image is set in a background of leaves and insects, her face solemn as though she knows she has to endure the continual pain.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=775&height=871)

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=792&height=1056)

Remedios Varo Uranga

Remedios Varo Uranga (1908-1963) was born in Spain. Her original name was Maria de los Remedios Alicia Rodriga Varo y Uranga, named to honor the Virgin of Remedies (Virgen de los Remedios), a child born shortly after her older sister passed away. As a hydraulic engineer, her father recognized his daughter's artistic talent and had her draw his technical plans to learn perspective and geometric shapes.Her life was also filled with an education from books based on science, mysticism, philosophy, and her Catholic faith, concepts found in her artwork. Initially, she attended the Escuela de Bellas Artes as a teenager. Uranga married and spent a short time in Paris before returning to Barcelona, a center for avant-garde artists. In 1937, she left her husband in Spain to fight the civil war and fled to Paris, where she had several affairs before escaping to Mexico when the Nazis invaded Paris. Uranga remained in Mexico for the rest of her life. During her early career, she demonstrated elements of Surrealism and spent her time in Paris with other Surrealist artists working as an illustrator for avant-garde magazines. During her earlier period in Mexico, muralism was the dominant artistic venue, Surrealism not acceptable. Other artists fled to Mexico to escape the war in Europe, forming a local art colony and bringing changing ideals of art.

The allegorical styles of Renaissance art stimulated Varo's art, concepts she brought to her Surrealistic paintings. She generally used oil on prepared Masonite panels, painting with delicate brushstrokes applied closely next to each other. The female Surrealists were not accepted into the male echelon of artists. The female artists had to develop different characteristics, and Varo generally displayed images of women in defined spaces, mostly with androgynous and spiritual figures. Ascension at Mount Analogue (7.8.6) depicts the lone figure awakened and starting a long ascent up the mountain. The figure seeks "a golden alpine flower that could be picked only if one did not want it; a flower said to be the source of spiritual purification, inner peace, and immortality." [4] The flower symbols for spiritual refinement and the transformation of the person. Varo uses red-orange as the robust color of the gown and wings to act like sails. The figure moves from the cave and faces the mountain; the mountain is a frequent symbol of spiritual transformation as a connection between the earth and the sky. Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst (7.8.7) portrays a woman in the courtyard, her face imprinted in the fabric of her gown, a disembodied head she appears to be dropping into the pool, and little emotion on her face. The basket under her cloak contained what Varo defined as "yet more psychological waste." [5] As she continues along the pathway of self-reflection, she will lose more waste. Varo used bright colors positioning the olive green against the yellow-brown walls. The white-winged headdress and white head move the viewer around the image. The clouds in both images were created with soufflage, blowing the paint on canvas with a straw, giving an otherworldly appearance.

_Remedios_Varo_-_Ascensin_Al_Monte_Anlogo_(5579572452).jpg?revision=1)

Leonora Carrington

Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) was born in England; her father gained his wealth in manufacturing. Numerous tutors and governesses educated her, only to be expelled from different schools for poor behavior. Despite her father's disagreement, she finally attended art school in London. Carrington saw the works of Max Ernst at a Surrealist exhibition in London and was attracted to his work and Ernst himself. When they met in person, Ernst left his wife, and he and Carrington moved to France, supporting each other's careers. At the onset of World War II, Ernst, a German, was arrested by the French government as a hostile alien, released by the intervention of his friends. The Nazis invaded France shortly after, and the Gestapo arrested Ernst as a degenerate artist. He escaped to the United States, leaving a devastated Carrington behind. She went to Spain and suffered a mental breakdown. Her parents hospitalized her, and she was treated with highly potent drugs. Carrington escaped to the Mexican Embassy, seeking refuge. During this time, Ernst married and never resumed their relationship. Carrington married Renato Leduc, the Mexican Ambassador, as a marriage of convenience and a way to travel to Mexico under diplomatic immunity. Although she divorced Leduc, she lived in Mexico for the rest of her life, marrying again and having two sons. Carrington was active in the feminist movement in Mexico and wrote many articles about issues of masculine authority or Surrealist-themed novels, including The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington or Down Below.

As a rebellious daughter, Carrington frequently included a woman trapped in creepy situations, crumbling houses, or claustrophobic enclosures. A monster or religious clergyman or another restraining persona might imprison her. The images are a reflection of her own tumultuous early life. Her painting, Self-Portrait (7.8.8), depicts a female figure with wild dark hair in a chair. Carrington frequently included horses in her paintings as representations of freedom, the horse her alter-ego. The white horse, her surrogate, is running free outside the window, the moving, tailless hobby horse trapped inside the room. The room is devoid of any furnishings except the chair. The hyena dances in front of her outstretched hand, imitating her posture.

Carrington also used the hyena in her paintings and writings, often a surrogate for her image. In one story she wrote, a debutante brought a hyena to the party to prove the power of women. Carrington told an interviewer, "I'm like a hyena; I get into the garbage cans. I have an insatiable curiosity." [6] In the elaborate labyrinthine, Ulu's Pants (7.8.9), characters are based on Carrington's interest in Celtic mythology. The significant figures line the bottom of the painting as though actors are aligned on the stage in a play. As a symbol of fertility and birth, the egg guards the opening along with the red-headed blob of a figure. The other figures wait at the gate as distant amorphous characters try to find a path through the secretive maze.

-1.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=745&height=993)

Carrington also made multiple oversized bronze surrealistic sculptures (7.8.10) using her recurring animal themes of hyenas, horses, and even half-crocodiles, some resembling ghosts or giant women, winged animals, or a conglomerate of an animal. The sculptures were based on folklore or myths, often in dream-like formats. She did not define the meaning of her sculptures, preferring the viewers to develop their assumptions and thoughts when they observed her work.

Kay Sage

Kay Sage (1898-1963) was born in New York; her father was wealthy from the timber business and a longtime state senator. Her parents divorced shortly after Sage was born; her mother moved with Sage to Europe. Her father supported her, and she attended private schools and formal art training. She married in 1923 and, for ten years in Italy, lived a socialite's life which she considered years thrown away with little purpose, then divorced her husband. Sage moved to Paris and became enamored with Surrealism, painting and exhibiting her work. She also met her next husband, Yves Tanguy, a close friend of André Breton. Although still married, Tanguy was separated from his wife, and after meeting with Sage, he divorced his wife. Sage had a lot of money from her father's estate and frequently helped support other artists, sometimes accused of being arrogant and deemed a princess. When Germany invaded Poland, starting the war, Sage returned to America and helped establish a Surrealist community in New York City, complete with exhibitions. She married Tanguy in 1940, and they moved from their studios to a farm. Although she developed a moody or unapproachable character, she did gain a reputation as an artist. During their marriage, Tanguy was abusive; however, when he died in 1955, she was devastated and seldom painted afterward.

Unusual Thursday (7.8.11) depicts a scene of a desolate landscape of architectural, pyramidal shapes in beige colors and deep shadows from an unseen sun. An eerie skeletal shape stands in the foreground, draped in a red cloak. Critics felt she had "a feel for drapery as well as for architectural forms…the work is seen as 'strong and attractive,' and the use of color' persuasive.'" [7] In the Third Sleep (7.8.12), she displays her ability to develop the draping images and the large divided shapes that rise out of the structure, jutting across the stark landscape. Again, Sage used a limited palette, giving white the primary position and deep shadows across the structure. Two small shapes appear as buildings; white and shadows balance the central shape as a small red wall running through the structure encircling the parts. As in both paintings, Sage uses a flat monotone and cloudless sky with little change from the horizon upward. They both have a surreal, dream-like state found in the subconscious. Sage said, "Things are half mechanical, half alive." [8]

Tomorrow is Never (7.8.13) was painted after she stopped working for five months after her husband died. Sage used the imagery of landscapes to depict the subconscious and the psychological cycles of existence. She continued to combine surreal landscape backgrounds with draped figures trapped inside the lattice-like structures arousing positions of entrapment and disarticulation, the melancholy gray tones adding to the feeling. The image was her last major painting before she committed suicide in 1963.

Dorothea Tanning

Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012) was born in Illinois, attended the local high school, and spent a few years in college. She wanted to pursue art and moved to Chicago and then to New York in 1935, working as an illustrator in the fashion industry. A local gallery exhibited her work and introduced her to other Surrealist artists, including Max Ernst. Although Ernst was married, he left his wife and moved in with Tanning, whom he later married. Over the years, they lived in Sedona, Arizona, Paris, and New York. In Sedona, she found a place of unique views, prickly plants, immense red rocks, the arid desert, and bright blue skies. Tanning developed friendships with other Surrealist painters and writers, observing their methods as she taught herself the necessary skills. Many of them visited Ernst and Tanning in Sedona. Tanning used the characteristic Surrealist techniques of meticulous features with careful brushstrokes. Her early years and through World War II were her most productive. Over time, she also expanded her styles to follow new methods and movements. Tanning was always interested in literature and writing, and later in her long life, she focused on writing and publishing many poems.

In her early career years, Tanning's work was more exact figurative executions in dream-like settings and imaginative stories. Tanning wanted viewers to find hidden places and transformed images. She loved to include doors in her images (and dogs), adding doors everywhere; doors were open, closed, inside and outside, doors leading to nothingness. Many Surrealist painters used a repetitive element to create a thread in their paintings; Magritte's apples or Dali's clocks. Her doors brought the mystery, what was behind the door or where did it lead, doors appearing more sinister than welcoming.

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (7.8.14) displays the hotel corridor; the two girls dressed in tattered skirts appear to be sleepwalking as the enormous sunflower sends out menacing tendrils toward the girls. One of the doors is ajar with the light on, perhaps a refuge for the girls, an escape, yet what would happen if they entered the room? As Tanning said, "Behind the invisible door (doors), another door; more doors, no doubt, new dimensions, deeper down the rabbit hole." [9]

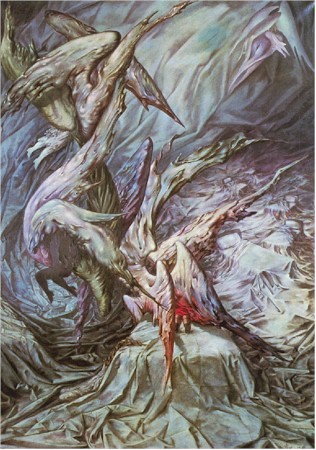

Tanning generally used female figures in her painting. Some feel she painted about her childhood and family; however, she stated she had a happy childhood and believed Enigma was good, forcing viewers to explore beyond what they see. She did grow sunflowers by her Sedona house and was fascinated by their giant size and used it to demonstrate the unknown forces in our lives, saying, "It's about confrontation. Everyone believes he/she is his/her drama. While they don't always have giant sunflowers (most aggressive of flowers) to contend with, there are always stairways, hallways, even very private theatres where the suffocations and the finalities are being played out." [10] A Guardian Angel (7.8.15) depicts a churning tangle of figurative translucent human shapes, all mirrored by the sails painted on the suitcase and the smoke ballooning out of the smokestacks. She used red to accent the small red lips and bouquet of roses above the bottom part of a female torso next to the torso of a man in blue pants. Tanning believed life was not smooth; the pleasure was explosive, the painting unsettling, a swirling vortex.

Florine Stettheimer

Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944) was born in New York as one of nine girls. Her father deserted the family, and her mother raised her. The family traveled and lived in both the United States and Europe. When Stettheimer was ten, she attended a boarding school in Germany and studied art. During their European travels, she spent time in museums and galleries, continued private lessons, and studied the Old Masters. Stettheimer graduated from the Art Students League in New York, expanding her ability to paint in the traditional European portraiture style with further European study. When World War I started, Stettheimer, her mother, and her sisters moved back to New York. The family became the center for artists, writers, musicians, and actors. Her sisters created extravagant dishes of food and drinks and continuous parties for people who gathered and could be themselves regardless of sexual orientation (gay and lesbian relationships were illegal at the time). All the visitors' elaborate, colorful, and creative clothing influenced Stettheimer's design. Leading feminist art historian Linda Nochlin defined Stettheimer's work as "subversive rococo," a form of undercutting the sexism in the art world found in the twentieth century.[11] Stettheimer used flowing lines, small delicate shapes and forms, and lighter colors. Her figures were adorned with jewels, lace, flowing materials, and other decorations.

Stettheimer's Cathedral series defined her work with flat, simplified images, pastel colors contrasted by bright reds, intensive pinks, and the extensive use of gold. In some of the areas of the paintings, Stettheimer used thin brush strokes, and in other parts, she used a palette knife to apply thick, heavy paint. The paintings were large, each one 152.4 x 127.3 centimeters. The four paintings depicted the pursuits of the wealthy and privileged in art, business, and theater. The works demonstrated the glitter and glamour of the period for those who had money, including her life with a wealthy family. When Stettheimer came to New York from Europe, she wrote:

Then back to New York

And sky towers had begun to grow

And front stoop houses started to go

And life became quite different…

Which I think is America having its fling

And what I should like is to paint this thing.[12]

The four paintings, The Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue (7.8.16), The Cathedrals of Art (7.8.17), The Cathedrals of Wall Street (7.8.18), and The Cathedrals of Broadway (7.8.19), were based on Stettheimer's vision of New York City and the institutions of the city. The Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue were founded on people's love of lifestyle pursuits and how the wealthy shopped and ate in the luxurious temples of New York City. The Cathedrals of Art depicted the gathering of critics, gallery owners, and photographers who controlled the success or losses in the art world. The Cathedrals of Broadway displayed the atmosphere found in the theaters of New York. Spotlights and neon lights illuminated the scene as the wealthy gathered for an evening of entertainment. The images in The Cathedrals of Wall Street illustrated America's belief in money and the manipulation of Wall Street. All the paintings represented the main ingredients of the rich in New York City, showing business, art, formal lifestyles, and money. Each of the paintings contained multiple images presenting a show of different scenes. Each mini-scene was created as a satire or frivolous depiction of serious activities, a period of the gilded age finally coming to a crash.

"She had almost a cinematic sensibility. She wanted to tell the whole story." Artist Joan Snyder reflects on Florine Stettheimer's "Cathedrals" paintings in this episode of The Artist Project—an online series in which artists respond to works of art in The Met collection.

Maria Izquierdo

Maria Izquierdo (1902-1955) was an artist from Mexico who created esoteric paintings, often focusing on women and their concerns. She was enrolled at the art school where Diego Rivera worked and developed a relationship with Rivera. She had to leave the school, and later he was forced to resign. Izquierdo's work often incorporated themes of loss, consequences, traditional Mexican values, and feminism – although she also rejected being called a feminist. The esoteric quality of her work placed her in the Surrealist category, though she also rejected that identification. The cover of an art book portrays her image, The Racket (7.8.20). Various objects are placed in distinctive ways and viewable from different levels resembling Surrealism. The darkness out the open window and past the tunnel brings the quality of a hallway. As seen in her other works, she brings the feeling of the experience found on a long journey to freedom, in the open air, out the window.

The high point of her life was when her dream of painting a government-sponsored public mural in Mexico was realized, only to be canceled. Izquierdo was rejected because her mentor, Diego Rivera, interfered. Along with David Alfaro Siqueiros, Rivera claimed she was not experienced enough to complete the project. Undoubtedly, her focus on the concerns of the female also played a part. The project was canceled, leading to the artist's suffering. Izquierdo was a professional artist recognized internationally and was the first female Mexican artist to exhibit her work in the United States. Today she is often overlooked and overshadowed by her contemporary, Frida Kahlo.

Izquierdo started painting still lifes combined with landscapes in the 1940s using common Mexican themes. Naturaleza Vivia (7.8.21) is a series of still life reminiscent of a picnic in Mexico. Local fruits and shellfish are arranged on the table, and the watermelon is cut and ready to eat. In the background, Izquierdo painted an extensive landscape moving far into the horizon with barren trees and desert-like land—the colorful abundance of food sitting on the table in sharp contrast to the surreal, dry background. Calabazas con Pan de Muerto (7.8.22) is an image of pumpkins with bread. The ornate bottle in the background was formed in the shape of the Virgin, and the bread was in honor of the Mexican holiday, the Day of the Dead. The background of the wall and sky demonstrated the incorporation of landscape and still life. Izquierdo emphasized more of her Mexican heritage in her later works. Her creations of still lifes were a radical departure from her other artist peers.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/leonora-carrington-rewrote-the-surrealist-narrative-for-women

[2] Retrieved from https://www.sfmoma.org/artist/frida_kahlo/

[3] Retrieved from https://www.fridakahlo.org/self-portrait-with-monkey.jsp

[4] Haynes, D., The Art of Remedios Varo, Issues of Gender Ambiguity and Religious Meaning, Woman's Art Journal, Spring/Summer 1995, 16/1, p. 31.

[5] Derks, M. (2011). Translating Magic: Remedios Varo's Visual Language, University of Missouri-Kansas City, p.55.

[6] Wise, S. (2019). Leonora Carrington: A Bestiary, Western Kentucky University, p. 20.

[7] Suther, J. (1997). A House of Her Own: Kay Sage, Solitary Surrealist, University of Nebraska Press, p. 111.

[8]https://artmuseum.williams.edu/kay-sage-serene-surrealist/

[9] Retrieved from https://lucywritersplatform.com/2019/04/03/dorothea-tanning-at-tate-modern/

[10] Retrieved from https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/tanning-eine-kleine-nachtmusik-t07346

[11] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/artists/5657

[12] Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2...rbara-bloemink