7.6: Harlem Renaissance (1918-1930s)

- Page ID

- 216463

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Introduction

In 1865, the Civil War ended, and hundreds of thousands of enslaved people were suddenly freed with the promise of participation in American life and an opportunity for self-determination. By the end of the 1870s, white supremacy restructured local and state laws, the "Jim Crow laws," taking away the right of African Americans to the promised Freedom and relegating them to poverty and powerlessness. A few people escaped the legislated constrictions, but most formerly enslaved people had to work as sharecroppers. At the same time, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) terrorized the southern countryside with lynchings and intimidation. The fundamental rights of the African American population were destroyed, segregation became the law, and voting rights were erased.

At the beginning of the new 20th century, the economies in the northern and Midwestern states were booming, and African Americans in the south saw the opportunity for economic advancement, jobs, education, and a more tolerant environment. Thousands of African Americans became part of the Great Migration, moving to the bigger cities in the North and West. A small region covering only a three-square-mile sector of Manhattan called Harlem developed into a significant location for African Americans moving from the south, people determined to build a new life and identity. Part of the migration included people of all backgrounds, talents, and abilities. Harlem became a major cross-disciplinary artistic center of African American artists, writers, and entertainers, developing one of the country's most critical cultural movements—the Harlem Renaissance. People in other cities also participated in the movement, but its heart was Harlem. The poet Langston Hughes wrote, "…artists who create now intend to express our dark-skinned selves without fear or shame."[1] During the period of the Harlem Renaissance, Harlem was known as an epicenter of American culture. "The neighborhood bustled with African American-owned and operated publishing houses and newspapers, music companies, playhouses, nightclubs, and cabarets. The literature, music, and fashion they created defined culture and "cool" for blacks and whites alike, in America and around the world."[2]

With the end of the 1920s and the stock market crash in 1929, the Great Depression ended prosperity throughout the country and Harlem. The Renaissance and culture developed in Harlem expanded worldwide, changed the perception of African Americans, challenged the racist stereotypes of southern Jim Crow, and illuminated the talents and capabilities of the people living in Harlem and other cities.

- Laura Wheeler Waring (1887-1948)

- Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877-1968)

- Augusta Savage (1892-1962)

- Loïs Mailou Jones (1905-1998)

- Selma Burke (1900-1995)

Laura Wheeler Waring

Laura Wheeler Waring (1887-1948) was born in Connecticut; her family ancestors had been active in anti-slavery events; her father was a minister, and her mother, was an artist and a graduate of Oberlin College. Waring graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1914, receiving a scholarship to study at an academy in Paris. However, her time in Paris was cut short when World War I started, and she returned to the United States. Waring married her husband, who was a university professor. After the war, she went back to Paris and enrolled in one of the academies, a time she started to paint portraits. Her style changed, becoming more realistic with vibrant colors. Her artwork focused on portraits of prominent African Americans who achieved success across multiple disciplines and illustrated numerous magazine covers and articles. In addition to pursuing her work as an artist, she taught school during her long career.

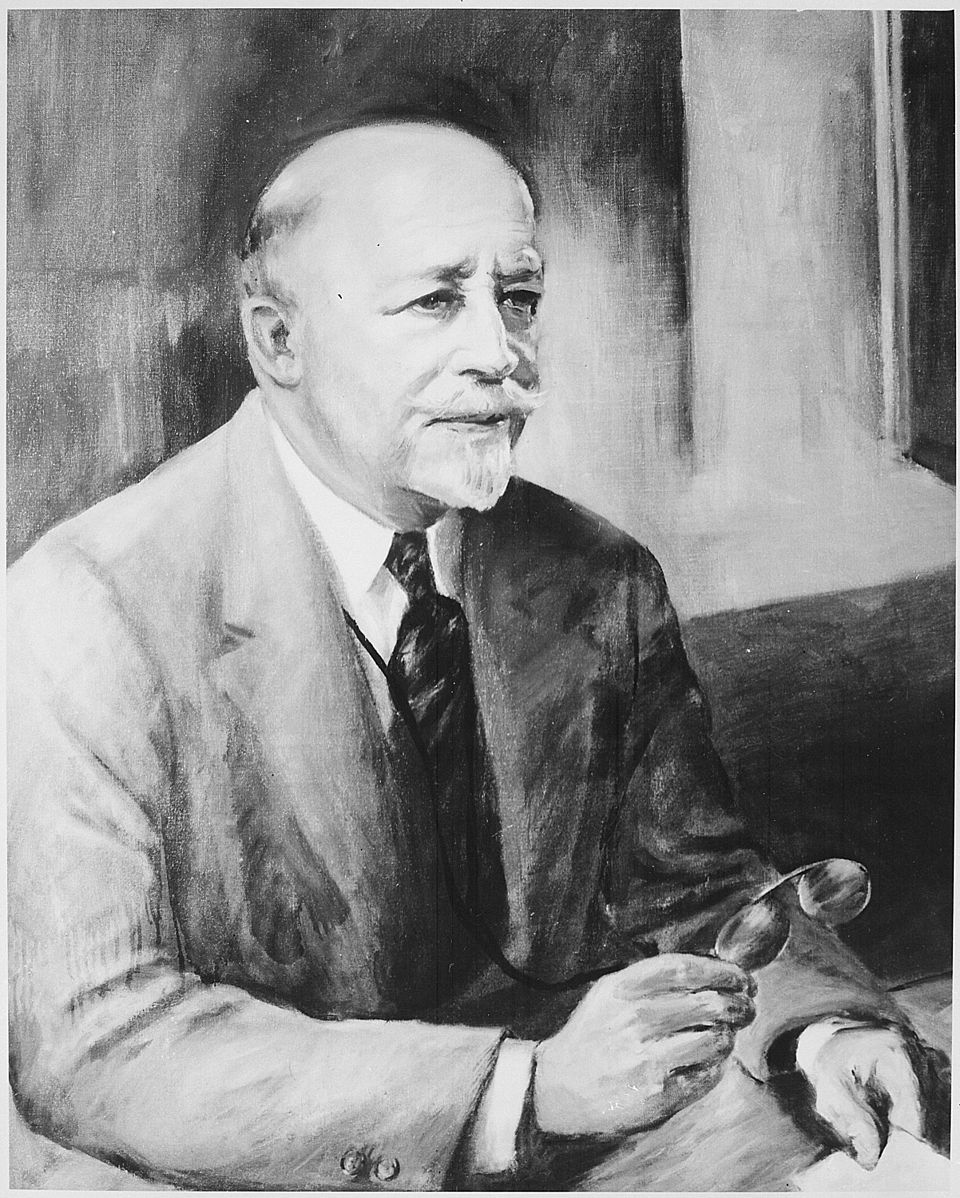

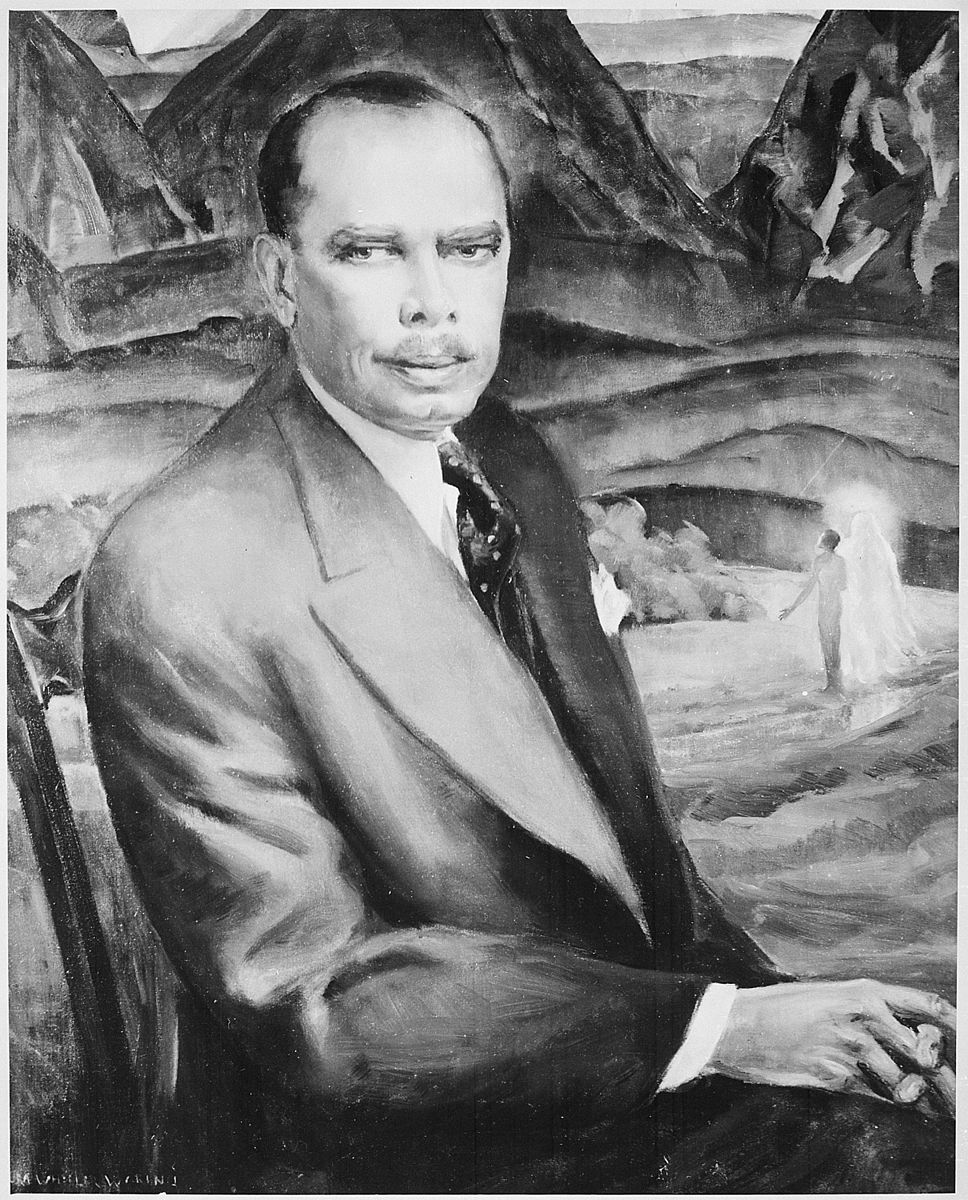

One of her first successful portraits was of Anna Washington Derry (7.5.1), an older woman who lived at the school in Cheyney where Waring taught. The painting earned her $400 and a gold medal from the Harmon Foundation, at the time, the only woman to receive the award. The Harmon Foundation commissioned her to paint a series, "Portraits of Outstanding American Citizens of Negro Origin."[3] This set of portraits earned her the most recognition, and they toured the United States to fight stereotypical beliefs and demonstrate the careers and successes of the people in the portraits. The series also included work by Betsy Reyneau. Some of the paintings in the series included: Alma Thomas (7.5.2), a fellow artist; W. E. B. Du Bois (7.5.3), a writer, historian, civil rights activist, and a founder of the NAACP; and James Weldon Johnson (7.5.4), a writer and civil rights activist. The original paintings were completed in color.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877-1968) was born in Philadelphia; her mother was a hairdresser and a wig maker, and her father was a barber. Her parents encouraged the family to visit museums, play musical instruments, sing, and draw. When Warrick graduated from high school, she went to the Philadelphia College of Art to study sculpture and even won first prize for her modeling work. As with many artists, she traveled to Paris to further her education, eventually working with Auguste Rodin as she developed a style of building expression and emotion into her work. When Fuller returned to the United States, she received a federal art commission, one of the first given to an African American woman. In 1901, she married a psychiatrist, and they moved to Massachusetts and faced an uprising from neighbors who did not want them to move into the suburb. Within a year, the building she stored her sculpture work in Paris was destroyed in a fire.

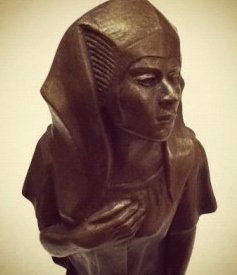

After a long hiatus and having three sons, she returned to sculpting and adopted African-American-based concepts. Ethiopia Awakening (7.5.5) was cast in 1922 as a full-sized bronze sculpture for a New York City exhibit. The female, emerging from her mummy-like wrappings, wears an Egyptian royalty headdress, her face defined as an African woman. The upper part of the torso appears to be reaching upward, the emergence of the African spirit. One of the most significant works by Fuller is the sculpture of Mary Turner (As a Silent Protest Against Mob Violence) (7.5.6). The work memorialized Mary Turner, who was brutally lynched when she was eight months pregnant. She holds an infant in the sculpture, grasping hands around the base. Turner's husband had been lynched, and when she denounced the lynching, the mob took her and brutally hung her upside down on a tree, where she and the infant died. The rough-hewn bronze on the bottom half shows the viciousness of the mob as she leans away from them. Fuller was a pioneer in depicting a lynching scene and continued creating many memorable sculptures. The video is a view of Fuller's life.

Meta Warrick Fuller's artwork celebrated African American heritage and cultural identity and resisted stereotypical representations in her depictions of the black body.

Augusta Savage

Augusta Savage (1892-1962), born in Florida, was creative as a child using the local natural red clay to make small sculptures and animals. Her father was a minister who strongly disapproved of her making clay figures, claiming they were graven images. She recalled, "My father licked me four or five times a week and almost whipped all the art out of me."[4] Fortunately, a principal in the high school recognized her talent and had her teach a clay class, generating in her a love for teaching and art. She married young and had one child, her husband dying right afterward. A few years later, she married again, divorcing after a few years. Savage continued to model clay figures, gathering prizes and commissions. By 1921, she left Florida for New York City and attended Cooper Union, graduating in three years. Savage applied for a summer art program in France and was rejected because she was a black person, a rejection spurring her interest in civil rights. She married again after graduation, her husband dying the following year. Although Savage received a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, she could not afford the living expenses or travel costs and had to turn down the opportunity. Savage finally went to France in 1929 with the help of fundraising parties in Harlem and other support groups, enabling her to study, research, and exhibit in Europe. When Savage returned to the United States, she established a studio for artists, facilitating education and support for many future artists.

Most of Savage's work is in clay or plaster; bronze is an expensive medium and is usually unaffordable. Gamin (7.5.7) is an image of a young boy whose personality is captured in his expressions and demeanor. His crumpled cap sits jauntily angled to one side as he tilts his head. His deeply set eyes and broad facial features give the boy a slightly defiant, appealing look. The boy was representative of the Harlem Renaissance concepts, a streetwise child defined by his African American heritage. The bust of the boy was made of painted plaster. Realization (7.5.8) only exists in photograph form. The project was for a commission by the Work Projects Administration in 1938, and its location is unknown. She made most of her work in clay and plaster; unfortunately, a significant amount of it was lost because it lacked the permanency of metal. Savage did not leave any notes about the work Realization, which appears to be about slavery and splitting family members to sell to different slave owners, the woman's top forced off. In the photograph, Savage almost seems to be joining the trio, supporting them in their agony.

Loïs Mailou Jones

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Loïs Mailou Jones (1905-1998) was interested in art as a child and encouraged by her parents to draw and paint. She attended a high school focused on the arts and had her first exhibition when she was seventeen. Jones studied art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and received her degree, followed by a graduate degree at the Design Art School in Boston. Eventually, Jones attended Howard University and received her formal Bachelor of Arts degree. Jones traveled extensively to study and understand European, Caribbean, and African art. Her art demonstrates a broad scope of interest, incorporating her training in textile designs, the use of costumes, different paint mediums, and collages. Jones went to Harlem every summer to study and work with other well-known Harlem artists. She spent much of her life teaching art and lecturing around the world. Jones wanted to create books with identifiable characters for children of color and illustrated several books. Initially, Jones was rejected by major museums because she was Black. So she sent her work to a few major museums where they did not know her, and she was accepted, starting her career. She lived a long time and, during her life, was an example of a successful and influential artist. Jones received several awards and honorary doctorates and was honored at the White House by the president for her outstanding achievements in the arts.

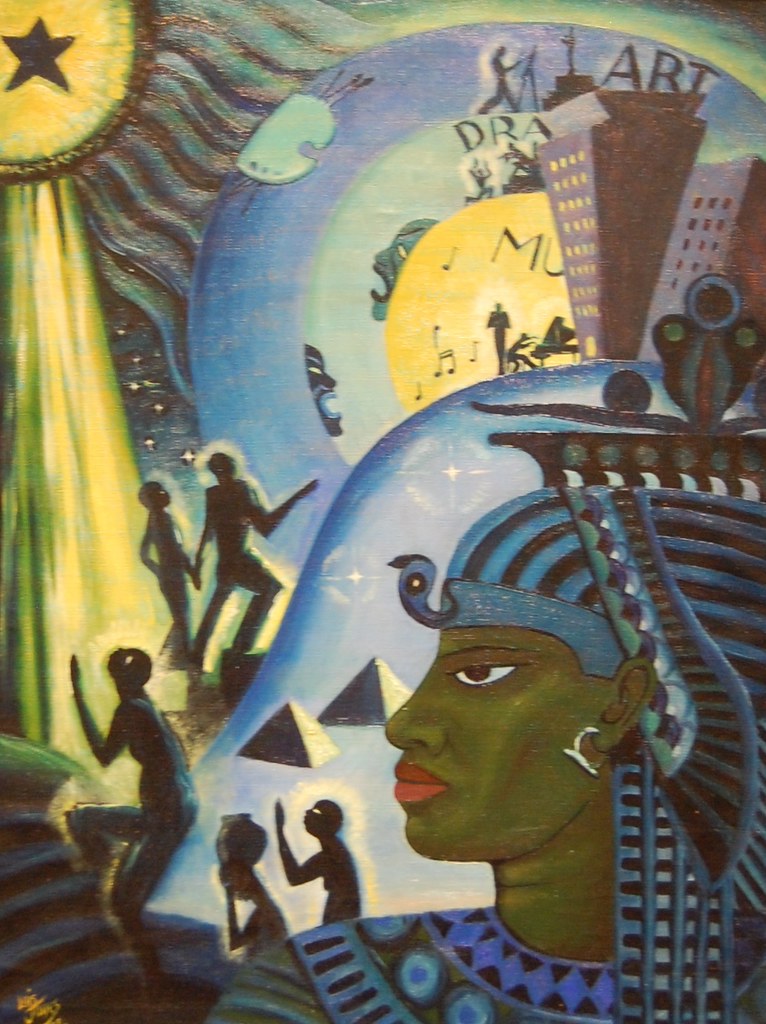

Jones used ideas of Egyptian motifs she learned when traveling to Egypt in her painting, expressing the concepts of the Harlem Renaissance. The art historian Tritobia Hayes Benjamin described the painting The Ascent of Ethiopia (7.5.9) by Jones as "a means of conveying profound respect for the Black experience, with a sympathetic and dignified treatment."[5] The resplendent pharaoh and figures move toward the city. Black artists, actors, and musicians are expressing their talents in the city. Jones's image linked the past with the future, demonstrating the influences of ancestors on modern artists. Jones used a muted palette of blues and browns with yellows as the accenting color. The painting has multiple points of interest, from the elegant pharaoh, the walking figures, words, and artists performing their work. Les Fetiches (7.5.10) is a group of randomly grouped African masks and figurative fetishes. Masks were made to project personal or cultural images. Jones spent time studying masks from Africa and other non-Western civilizations. She found her ancestry in the African masks and created the image to demonstrate the variety of masks used in the diverse and widespread African cultures. Jones abstracted the five masks using sharp planar lines and different color contrasts. The video is an interview with Jones.

Loïs Mailou Jones interviewed on Good Morning America at the age of 90 for Black History Month.

Selma Burke

Selma Burke (1900-1995) was born in North Carolina, one of ten children. Her father was a minister in rural North Carolina, and Burke played with the clay by the river. She experienced the sensation of squeezing the clay through her fingers and forming shapes, developing her interest in sculpture. Burke told the New York Post in 1945, "One day, I was mixing the clay, and I saw the imprint of my hands; I found that I could make something…something that I alone created."[6] Burke was discouraged from pursuing art, and she graduated from St. Agnes Training School for Nurses and became a nurse. She married in 1928, and the marriage only lasted a year because her husband died. She went to Harlem in New York and initially worked as a private nurse for a wealthy woman. While Burke was there, she took art classes and met people in the Harlem Renaissance group, especially Augusta Savage, who became her mentor and encouraged Burke to learn more about art. Burke traveled to Europe and obtained a scholarship to Columbia University, where she received her master's degree. Burke taught art to children at the Harlem Community Arts Center for a while before becoming an active sculptor. Her work usually focused on creating figures and busts, especially prominent African Americans. Burke lived to be ninety-five, and her last sculpture was the 2.7 meters high bronze statue of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1980.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=489&height=734)

When World War II started, she enlisted in the Navy as one of the first African American females. While driving a truck, she injured her back. As Burke recovered, she also entered a contest to create a bronze relief of President Franklin Roosevelt (7.5.13). She did not want to work from a photograph and asked Roosevelt if he would sit in person for her. Roosevelt accepted the request and sat twice while Burke sketched him. Before many citizens had no civil rights and Blacks were still segregated, a white president sat in a pose for a black artist. A third sitting was scheduled; unfortunately, Roosevelt died before the appointment. At the time of the sitting, Roosevelt was ill and aged. Burke chose to capture his image as a younger man. She said, "I made it for tomorrow, and tomorrow, I don't want people to feel something about a wrinkled old man. I want to give the feeling of a strong Roman gladiator that we could feel was strong and would lead our country."[8] The bronze plaque included the Four Freedoms added above the image; Freedom from want, Freedom from fear, Freedom of worship, Freedom of speech. The video reviews Burke's work.

Born in Mooresville, Selma Burke was a groundbreaking sculptor and one of the few women represented in the Harlem Renaissance. Her portrait of President Franklin D. Roosevelt is likely the model for his image on the back of the U.S. dime. She is also known for her public sculptures of African American figures, including Duke Ellington, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Booker T. Washington.

[1] Hughes, L. (2015). The Weary Blues, Knopf; Revised edition (10 February 2015).

[2] Retrieved from https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/new-african-american-identity-harlem-renaissance

[3] Leininger-Miller, T. (2005). "A CONSTANT STIMULUS AND INSPIRATION": LAURA WHEELER WARING IN PARIS IN THE 1910s AND 1920s. Source: Notes in the History of Art, 24(4), 13-23. Retrieved July 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23207946

[4] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artist/augusta-savage-4269

[5] Retrieved by https://blog.mam.org/2020/07/13/lois...t-of-ethiopia/

[6] Retrieved from https://www.womenshistory.org/educat...es/selma-burke

[7] Retrieved from https://www.sartle.com/artwork/untit...ld-selma-burke

[8] Retrieved from https://www.ourstate.com/artist-selm...d-dime-design/