7.5: Expressionism (1912-1935)

- Page ID

- 216464

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Introduction

At the beginning of the new 20th century, European artists were dissatisfied with the academic standards and style of the art community. They began experimenting with new ideas for the modern world and expanding cities. As part of the European transformations, Expressionism was born in Germany; art charged with emotions and subject matter found in urban settings. The director of a German museum stated, "The German artist looks not for harmony of outward appearance but much more for the mystery hidden behind the external form. He or she is interested in the soul of things and wants to lay this bare."[1]

As part of a pre-World War II change, Expressionism included art, literature, theatre, and music, fueled by young people from Germany and Russia pushing for change in the social and political structures. The movement started at the turn of the century. It continued until the 1930s when the National Socialists (Nazis) grew in power, a government rejecting Expressionism in all forms and condemned it as 'degenerate.'

The Expressionists used bold colors and unusual forms to create expressive, exaggerated images. Instead of duplicating realistic images, the artists wanted to express inner feelings and used simple shapes and broad brushstrokes to illustrate their emotional ideas. Two groups were dominant in the movement, Die Brucke (the bridge), led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Der Blaue Reiter (the blue rider), started by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc.

The new art styles of Expressionism flourished, were displayed in museums, and were purchased by collectors. In 1933, after Adolf Hitler was named to head the government, the Nazis started dismantling the artwork and removed 20,000 artworks from the museums owned by the state. "In 1937, 740 modern works were exhibited in the defamatory show Degenerate Art in Munich to 'educate' the public on the 'art of decay.'"[2] The pictures in the exhibit were hung overlapping or askew; graffiti was written on the walls with crude sayings. The work was defined as blasphemous, art defaming women or art from Jewish or communist artists. The exhibition encouraged the people to see the art as a plot against Germany. Many of the works were subsequently destroyed, sold to make money for the government, or hidden and discovered much later. Artists in this section:

- Marianne Werefkin (1860-1938)

- Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907)

- Gabriele Münter (1877-1962)

- Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

- Anita Malfatti (1889–1964)

Marianne Werefkin

Marianne Werefkin (1860-1938) was born in Russia and started as an art student early in her life. However, her right hand was shot during a hunting excursion in her twenties, making it difficult to use and only recovering through persistent practice. When she married and moved to Germany, she suspended her painting until her late forties. She exhibited with a group of Expressionist artists, including Kandinsky and Marc. With the advent of World War I, she moved to Switzerland, where she remained. One of the few women artists, her work was abstracted yet expressed how she felt about the human spirit, people set in scenes, hunched over, frequently displaying their poverty. She wrote about life in her diaries and once said,

One life is far too little for all the things I feel within myself, and I invent other lives within and outside myself for them. A whirling crowd of invented beings surrounds me and prevents me from seeing reality. Color bites at my heart.[3]

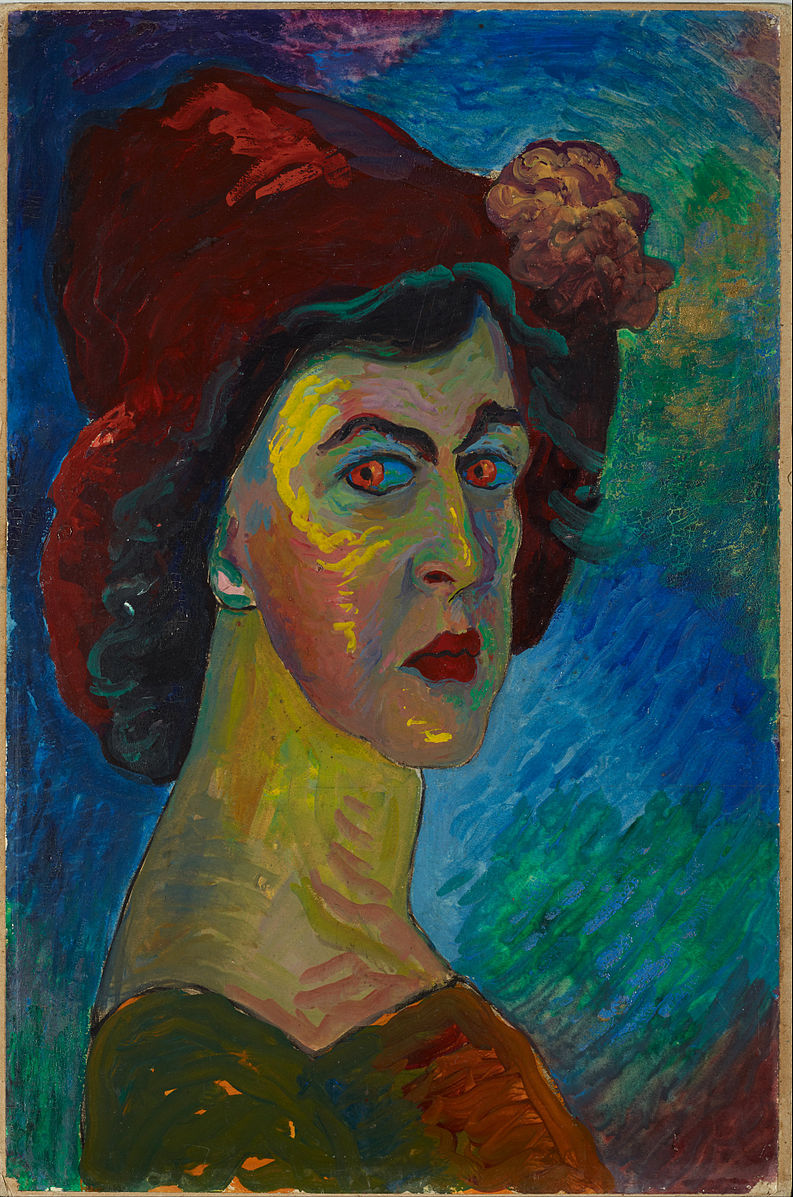

Werefkin painted her Self-portrait (7.7.1) when she was in Germany and part of the Expressionist group. She used deep greens and blues for the background with broad brushstrokes to contrast with the other colors of her face and clothes. She was heavily influenced by how the Post-Impressionists used color and painted dynamic colors to portray emotions and intensity. Some historians deem her self-portrait one of the more extraordinary self-portraits in art.

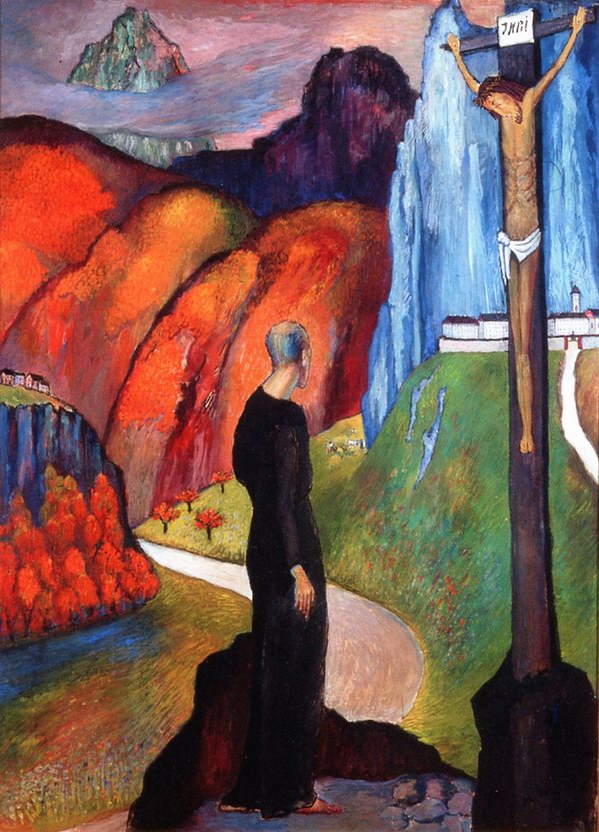

The Monk (7.7.2) reflected her interest in religion and the symbolic nature of religious concepts and icons. The crucifixion is found in many of her later paintings. The cross against the bright blue of the ethereal world is balanced against the dark or bold colors of the natural world inhabited by the monk. The mountains reflect her view of the world in Switzerland, a winding road through the mountain pass; the monk appears to focus on the road and reality instead of the cross and the suffering it implies. The bright reds and oranges are balanced by the dark purple mountain in the center and the soft blue on the right. The monk wears dark clothing, bringing a profound depth to the painting as he looks down the open road.

Paula Modersohn-Becker

Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), born in Germany, is considered one of the essential artists of early Expressionism in Germany. Her artistic ability was recognized when she was younger, and she trained with private instructors before going to Paris multiple times to study, including at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Although married, she and her husband frequently lived apart in Paris or Germany. She was trained in Realism and Neoclassicism; however, she abandoned those styles after being influenced by Cezanne and Gauguin and their bold colors and contours instead of the traditional realistic lines and expressed flatness. During her career, women painters seldom had nude females as models and did not paint nude females. Modersohn-Becker painted herself in many nude self-portraits, an unprecedented idea for female artists. Much of her information is from the daily diary entries, frequently writing about motherhood and if she wanted children. At age thirty-one, she had her first daughter, encountered pain in her leg from an embolism after the delivery, and sadly died when the baby was only nineteen days old.

According to [Diane] Radycki, Modersohn-Becker was a "daring innovator of gender imagery"—the first woman artist to create nude self-portraits and the first to paint nude images of mothers and children. As a result, Radycki credits Modersohn-Becker as being the first modern woman artist. As she states, Modernism's style and subject matter innovations begin with his [Picasso's] Cubism and her [Modersohn-Becker's] female bodies.[4]

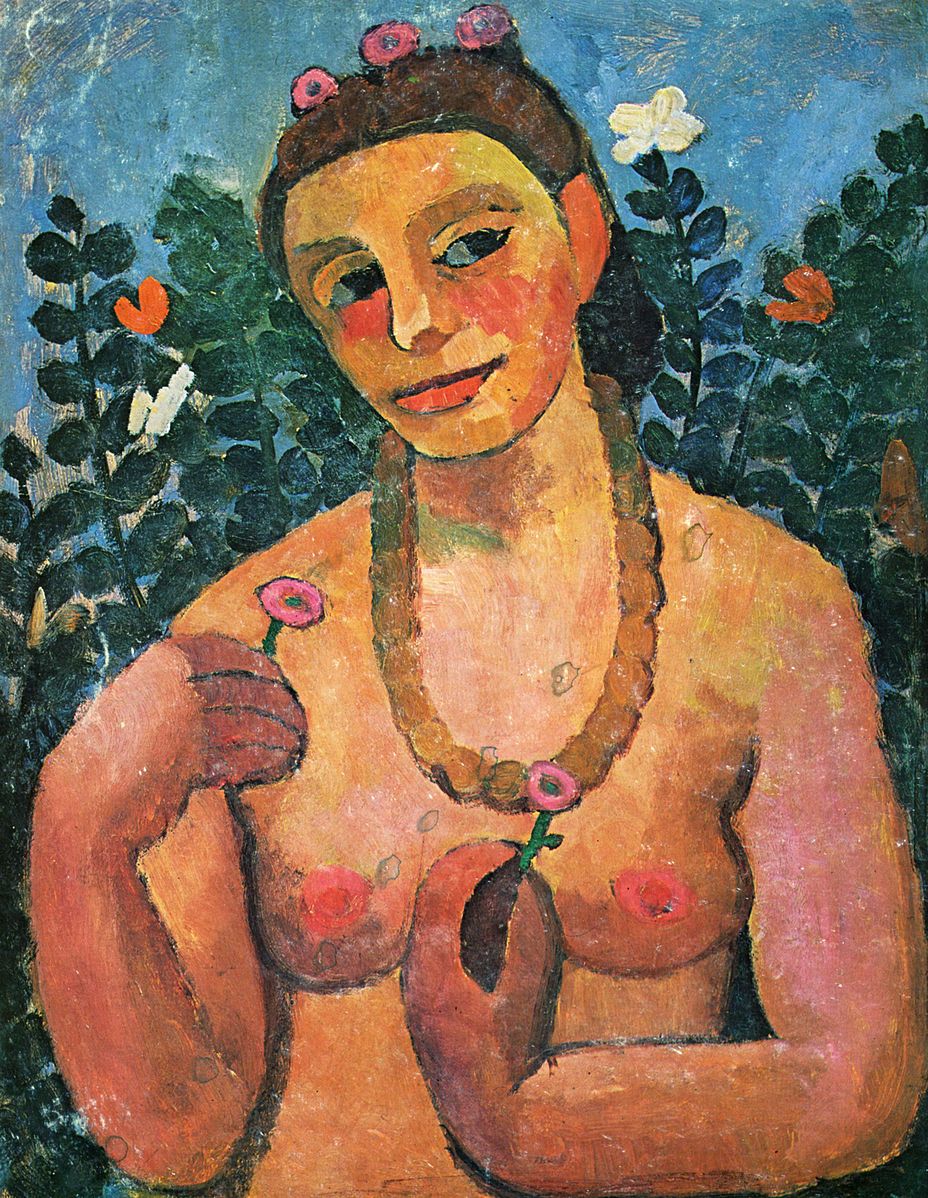

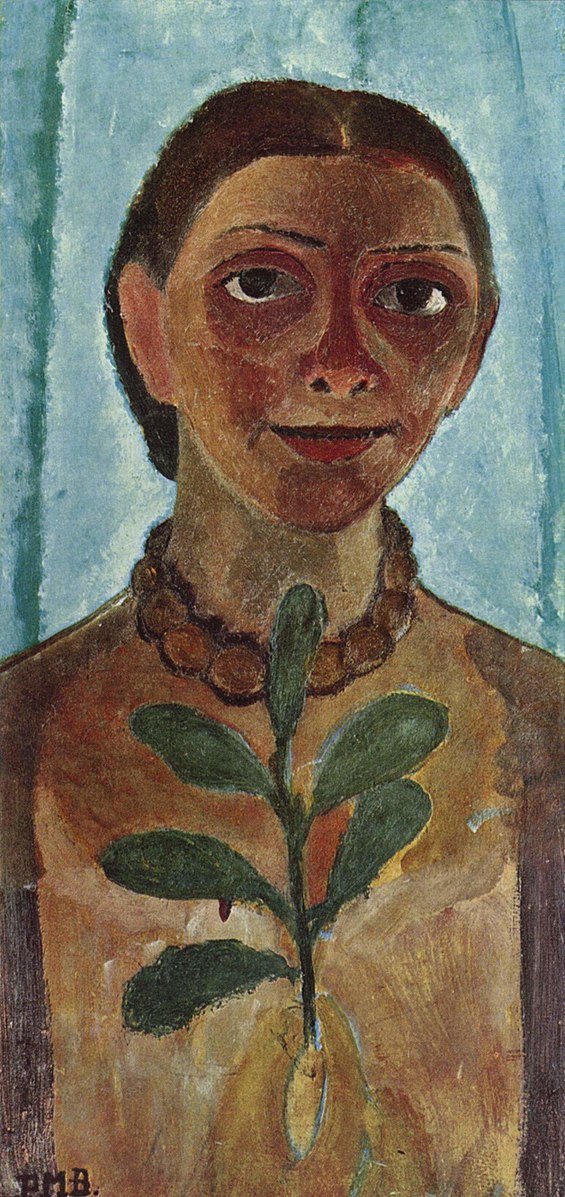

Self-Portrait, Nude with Amber Necklace Half-Length II (7.7.3), was exhibited after Modersohn-Becker's death, a painting she completed the year before. She looks straight at the viewer, not as the artist herself, but as the representative of women and their presence and beauty qualities. She is wearing an amber necklace, an object Modersohn-Becker frequently included in paintings, flowers decorate her hair, and the foliage in the background frames the image. In The Painter with a Camellia Branch (7.7.4), Modersohn-Becker grasps a branch from a camellia plant, a calm look in her oversized eyes and a gentle expression. She was swayed by Egyptian artwork and painted this image on wood in the same tall, narrow format used in Egyptian paintings. The face is in the shadows contrasted against the light blue background. This image was the last work she painted seven months before she died. In one of her earlier diary entries, she wrote, "I know that I won't live very long. But is that sad? Is a festival better because it's longer? And my life is a festival, a short, intensive festival." [5]

To ready Paula Modersohn-Becker's "Self Portrait" (1907) for MoMA's reopening in October, conservator Diana Hartman tackles the question of how to repair holes in the painting’s canvas. She figures out that a curved needle typically used in eye surgery might allow her to avoid removing the work from its original stretcher. And her inventiveness doesn’t end there: Using an adhesive made from a sturgeon bladder, she secures linen thread to the needle to darn the pieces back together with the help of a microscope. Hartman shows how she makes unobtrusive repairs, to keep viewers’ gaze focused on the portrait itself. “Just by doing this treatment,” Hartman says, “we’ve given this painting a breath of fresh air.”

Gabriele Münter

Gabriele Münter (1877-1962) was a founding member of the Blue Rider group of the German Expressionists. She was born in Berlin, Germany, and started drawing as a child. Her parents were upper-middle class and had enough money to educate Münter using a private tutor. She trained in a local artist's studio as an adult and attended the Damenschule (Women's School). When Münter was only twenty-one, both parents were deceased, leaving her enough money to be independent. Münter went to America to visit her sister, and when she returned to Germany, she started studying art in different schools and studios. At the Phalanx School, Münter learned to mark the canvas with a palette knife and use bright, bold colors. She also met Wassily Kandinsky at the school, who became her teacher and lover. Münter developed her technique of painting landscapes using dark outlines and bright, unmixed colors. In her diary, Münter wrote, "After a short period of agony, I made a great leap, from copying from nature, in a more or less Impressionist style, to feeling the content of things-abstracting-conveying an extract."[6]

Münter and Kandinsky spent ten years traveling through Europe and Africa, still returning to Germany. During World War I, she went to Switzerland, and Kandinsky returned to Russia. Münter stopped painting until the late 1920s when she moved back to Germany. By the 1930s, Germany was under the control of the Nazi government, and the Nazis condemned the modern art movements as degenerate. Münter hid much of her work and other works of the Expressionists. As the Nazis searched and destroyed the art of the Expressionists, the works hidden by Münter were never found by the Nazis. Later, she gave the hidden works to a museum in Munich, artwork saved by Münter's efforts to keep the art from the Nazi's fires.

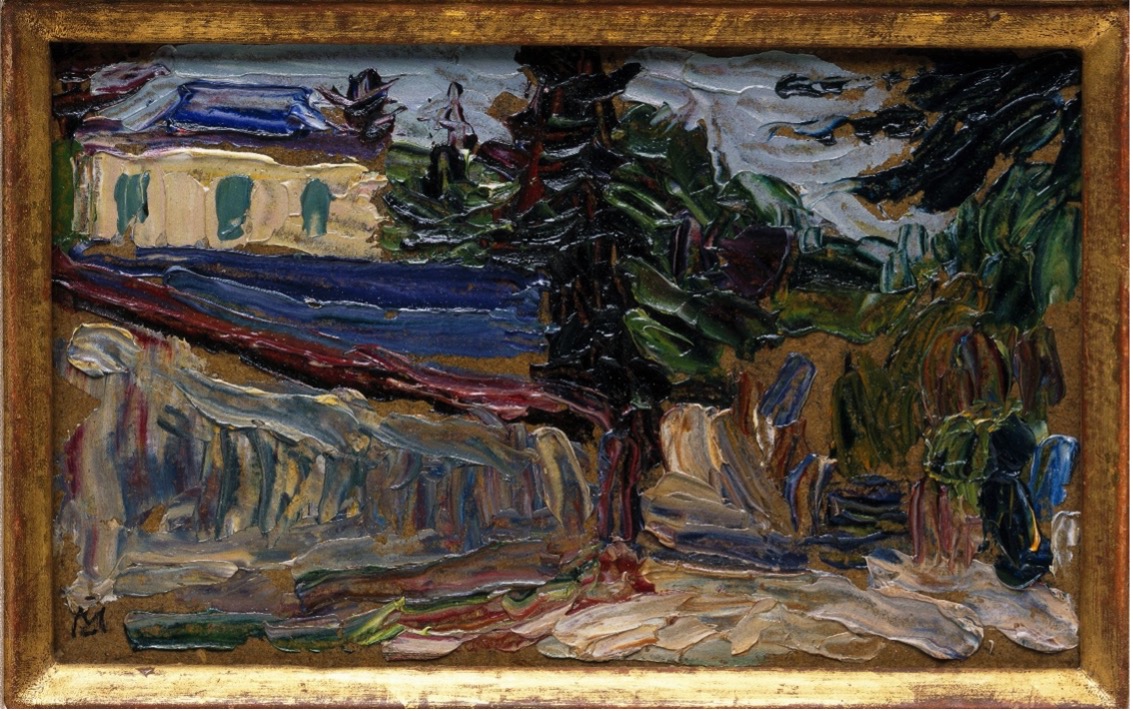

Münter painted on her boards by creating heavy, dark black outlines and filling the outlines in with thick, broad-brush strokes or a palette knife. She wanted the paintings to be spontaneous and painted quickly to fill in different colors. Münter used a palette of yellows, greens, and browns early in her artwork. Her later landscapes incorporated stronger colors with the addition of blues, greens, yellows, and accents of red. Countryside Near Paris (7.7.5) was painted when Münter traveled in Europe. She created the work "en plein air," working outside. She worked quickly and was known to paint a piece in one day. This painting demonstrates how she thickly applies the paint, with a significant amount of paint on her knife or brush. The effect is an image of the wind blowing through the trees and grasses. Münter used darker colors except for the bright yellow house in the background.

Nightfall in St. Cloud (7.7.6) is another of Münter's landscapes in the countryside of Paris. The painting is a tribute to how good she was with the palette knife and the application of colors. The river flows from one side as it widens to fill part of the image. The mix of colors gives the impression of the quick movement of the water. Trees jut out of the river sides, and she used color to develop depth. Of her landscape painting, Münter said, "My main difficulty was I could not paint fast enough. My pictures are all moments of life—I mean instantaneous visual experiences, generally noted rapidly and spontaneously. When I begin to paint, it's like leaping suddenly into deep waters, and I never know beforehand whether I will be able to swim."[7]

Gabriele Münter was a German expressionist painter who was at the forefront of the Munich avant-garde in the early 20th century. She studied and lived with the painter Wassily Kandinsky and was a founding member of the expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter.

Käthe Kollwitz

Modern sculptures demonstrate our need to understand the world, especially in the complex modern and ever-changing world, and Käthe Kollwitz (1867 - 1945), a German artist, created a body of work portraying eloquent accounts of the despair of human life, especially about the tragedy of war. Kollwitz was born in Prussia; her family was known as radical Socialists. She was talented as a child, and her parents provided a tutor when she was twelve. Kollwitz went to Munich to study painting and married a doctor who worked with the poor, allowing her to continually view the plight of the people. She did not attend any formal schools yet was a master of etchings, lithographs, woodcuts, and sculptures. She did take classes with the Union of Women Artists, an informal group because women were not able to attend the all-male academies. In 1919, Kollwitz was honored and elected to the Academy of Arts in Germany, the first woman. She was active in the academy until the Nazis seized power of the government and she was forced to resign in 1933. In 1943, during World War II, her home was bombed and much of her work and studio were destroyed.

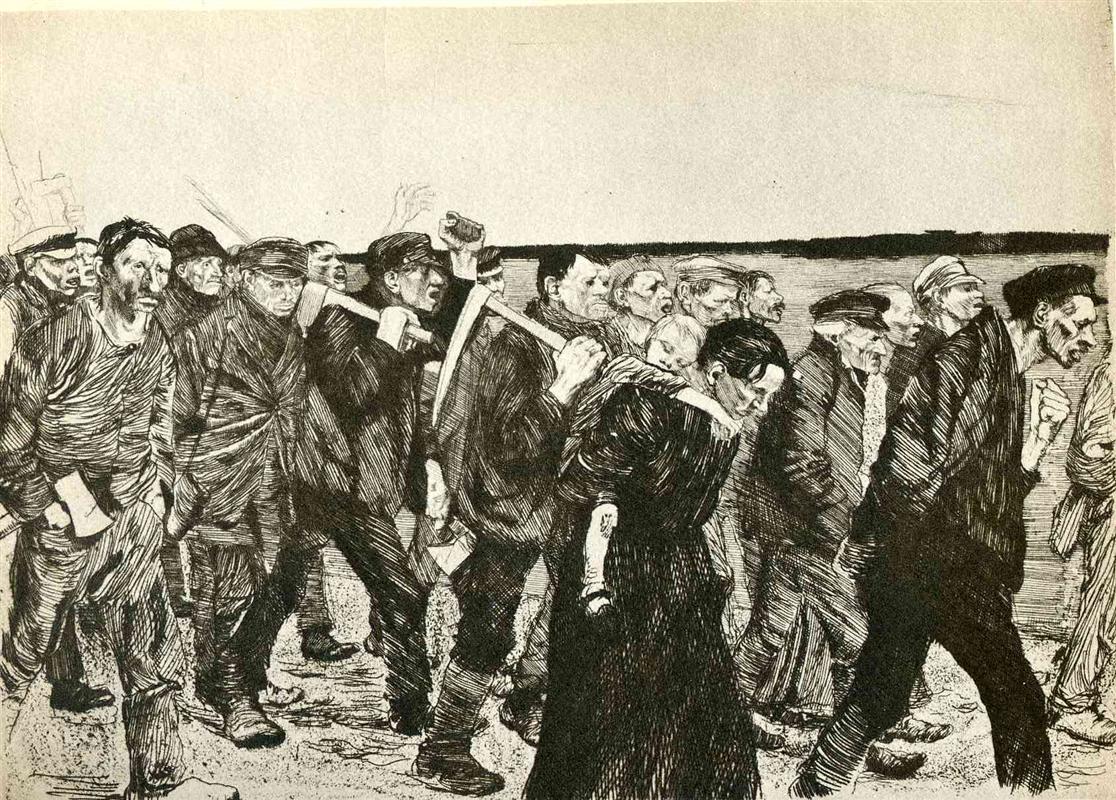

Using multiple mediums, including etching, woodcut, drawing, painting, and sculpting, she reproduced the emotions of poverty and war. The etching (7.7.7) was based on the play The Weavers in Berlin when the workers rallied at the employer's house who calls the military. In the scuffle, an old man is killed. Kollwitz generally based her work on images of poverty, infant mortality, and political unrest. Some of the people in the etching display anger while others are resigned to poverty and look down. Kollwitz successfully used a series of lines to define the people's clothing. Each character is composed of a different set of lines, some dark and heavily filled in and other with lighter lines. She also developed unique faces on each person. The video describes her work.

A brief artist's bio illustrated by selected works from the collection of McMaster Museum of Art, McMaster University.

The death of Kollwitz's son drove her to create the memorial Mother with Her Dead Son (7.7.8) for him. On the anniversary of her sons death, Kollwitz wrote in her diary, “I am working on the small sculpture that is the result of my sculptural experiments to portray old age. It has become a kind of Pietà. The mother is seated, her dead son lying on her lap between her knees.”[8] Mother with Her Dead Son shows a reflection of her pain, the loss of her son in the war. Kollwitz did not consider this a religious sculpture; rather it demonstrates the love of a mothers grief over the loss of her son. The statue is highly draped with folds of material encapsulating the son as she hugs him into her body. The statue is positioned in the center of a large room (7.7.9) creating a feeling of isolation which only enhances the emotions of suffering and sadness. The bronze memorial is a tribute to all the victims of war and tyranny.

Anita Malfatti

Anita Malfatti (1889–1964), a South American Brazilian female artist, painted in many European abstract modern art movements popular in the early 20th century while studying in Europe. She is thought of as the pioneer of modern art in Brazil. Malfatti was born in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and studied at Mackenzie College in Sao Paulo. However, Brazil did not have many art school and in the existing schools there was conflict about what art should be – traditional or modern. While she was at school in Europe, she learned to focus on the human body in the context of the new modern movements. Malfatti liked to distort parts of the body and used a very colorful palette. Sometimes she was inspired by Cubism's flattened and twisted effects, and other times incorporated strong, vibrant, and non-naturalistic use of a color like the Fauves. Her work was not well accepted in Brazil at first and she was a woman who did not follow proper feminine etiquette. Although she earned a one-person exhibition in Sao Paulo, an important event for a woman to have her show, she was rejected by academic art. A lack of a clear Brazilian identity in her works made her exhibition all that more controversial.

In The Fool (7.7.10), Malfatti created imagery generally upsetting the conservative Brazilian public. The art critic Monteiro Lobato said her work as "beastly" and "deformed," the latter a satirical play on the translation of her Italian last name ("mal fatti"); he declared her painting to be akin to art produced by the mentally insane, work born of "paranoia and mystification," and finally he dismissed her as "a girl who paints."[9] In the painting, the girls face is slightly distorted, her hair oddly arranged with the strong part in the middle. Malfatti's used highly contrasted colors, yellow as the focal point in most of the painting as the woman stands out. Even her face is made with the same strong yellow. Although, Malfatti used the cool contrast of blues and greens, the background is still prominent because of the strong, wide use of brushstrokes.

Malfatti's right hand and arm were atrophied, and she had to learn to write and paint left-handed. In many of her paintings of women she includes arms and hands in different positions. Paintings were still based European styles and the painting of the mixed race girl did not fit in the perception of proper art. In Tropical (7.7.11), Malfatti painted a classic Brazilian part of live. The young woman appears mixed race with dark skin, dark eyes and hair, and thick lips. She is holding Brazilian fruit in her basket and all the appearances of a peasant woman. The painting was highly critiziced and a group of artists rallied to support Malfatti, starting the change in Brazilian art. Anita Malfatti is considered the instigator of modernism in Brazil

[1] Kirchner – Expressionism and the City, Royal Academy 2003. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/2007pdf0926234509/http://static.royalacademy.org.uk/files/kirchner-student-guide-13.

[2] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3868

[3] Retrieved from https://www.lenbachhaus.de/collection/the-blue-rider/werefkin/?L=1

[4] Retrieved from https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2893&context=gc_etds

[5] Retrieved from https://arthistoryproject.com/artists/paula-modersohn-becker/self-portrait-with-a-camellia-branch/

[6] Retrieved from https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/arti...-munter-artist

[7] Retrieved from https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/openc...n/objects/4943

[8] Retrieved from https://www.kollwitz.de/en/pieta-sculpture-en-bronze

[9] Retrieved from https://smarthistory.org/modern-art-sao-paulo/