7.3: Cubism (1907-the 1920s)

- Page ID

- 135002

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Introduction

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque created Cubism a few years after the opening of the new century. They developed different ideas of how objects or figures were composed, becoming one of the most influential design concepts of the 1900s. Louis Vauxcelles, an art critic, wrote of Braque's landscape painting as Cubism because the images were formed into geometric shapes or "bizarre cubiques." The Cubist artists did not believe in the usual standards of how elements appeared in nature or concepts of proper perspective or foreshortening. Instead, they redefined the shapes and objects in their paintings into geometric forms, pulled them apart, and reformed them into overlapping and interwoven sections, allowing different perspectives of the three-dimensional parts of the object. The artists also accentuated the two-dimensional flatness of the surface, obscuring the concept of depth. They traded the traditional perspective of an imaginary distance for a way to hold the eye on the flat surface and experience three-dimensionality.

Cubism comprised two stages; analytical Cubism, the early form of Cubism in muted tones of blacks, grays, or ochres preventing color from interfering with the fragmented objects. The form also had intersecting and overlapping lines and surfaces, with multiple ways to view the object through the assemblage of deconstructed and reassembled parts. The works from 1908-12 used a palette evoking a somber feeling. By 1912 and synthetic Cubism, the shapes were simpler, full of bright colors, and frequently collaged with other materials. The parts were reassembled on top of each other similar to magazine displays on racks, with less focus on space and the ability to understand layers of shapes. Collaging and adding other resources like paper or newsprint was one of the more essential concepts of Cubism, ideas that permeated into future modern art. The concept of how to depict space and anything in space was defined in the Renaissance period. It had been the guiding ideal for artists until the Cubists, who blended space and objects into multiple angles.

In the early 1900s, female artists began pushing their way into the art world. Cubism provided a style with few restrictions and freedom for women to create new and different art. The period was also marked by a world war, revolutions, and new opportunities emerging from a restructured Europe. New educational prospects for female artists became available in many countries, and they could paint nude models. Cubist artists in this section include:

- Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979)

- Marie Laurencin (1883-1956)

- Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973)

- Natalia Sergeevna Goncharova (1881-1962)

- Lyubov Popova (1889-1924)

- Mary Harriet Jellett (1897-1944)

Sonia Delaunay

Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979) was born in Ukraine and sent to live with wealthy relatives in St. Petersburg, Russia, who traveled with her throughout Europe. In school, she was classically trained before moving to Paris. Her early work in France was influenced by the Post-Impressionists and the Fauvists and their uses of color. In 1908, she married an art gallery owner who helped her exhibit work and entered the art world so he could access her dowry and have a perfect cover for his homosexuality. She met Robert Delaunay at the gallery, divorced her husband, and married Delaunay in 1910. She said, "In Robert Delaunay, I found a poet. A poet who wrote not with words but with colors."[1] After their son was born, she transitioned from the concepts of perspective and natural appearance to experimenting with Cubism and the intersection of color. The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists were influenced by Michel Eugéne Chevreuil's concepts and his law of simultaneously contrasting colors. Both Delaunays, working with the theory, started painting with the overlapping planes and lines of Cubism combined through the concentration and vibrancy of color. A friend of the Delaunays described Cubism as Orphism, a more lyrical abstraction with bright and pure colors.

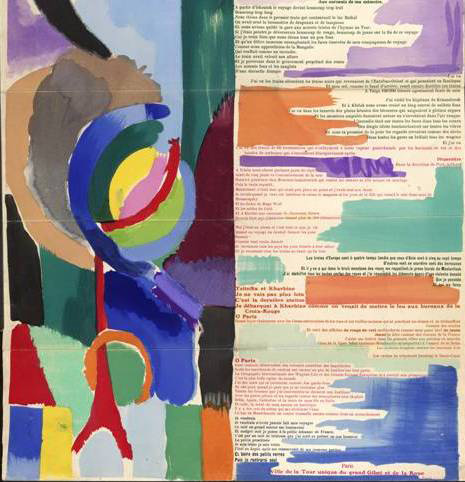

One of Delaunay's first major projects was the illustration of the poem of Blaise Cendrars, who wrote Prose of the Trans-Siberian and Little Jehanne of France. The book was two meters long and formed into an accordion-pleated book. Delaunay combined her design with the text, as seen in the last section (7.2.1). The book and her illustrations were well received and helped establish her talents. After the Russian Revolution, she lost financial support from her family in Russia. She started designing costumes and sets for the theatre and a successful clothing business. Later in her life, she continued designing textiles, jewelry, clothing, and tableware until she died in 1979 at 94.

Prismes Electriques (7.2.2) attracts light variations with color as the primary theme. The energy of the circular patterns moves throughout the painting as light is diffracted, bringing movement to the circles. The overlapping circles form curved spaces of primary colors and neighboring secondary colors. The rest of the painting has multiple geometric rectangular and oval planes. She was supposedly influenced by the glow of the electric streetlights and used Chevreuil's concept of color to produce light; she combined lighter and darker colors to create a similar pattern.

Sonia Delaunay was known for her vivid use of color and bold, abstract patterns, breaking down traditional distinctions between the fine and applied arts as an artist, designer, and printmaker.

Marie Laurencin

Marie Laurencin (1883-1956) was born in Paris and studied ceramics before changing to oil painting. She was romantically linked to poet Guillaume Apollinaire, associated with Metzinger, Braque, and Delaunay, and exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in concert with the Cubists. She married a German, causing her to lose French citizenship because a woman had to take her husband's citizenship. During World War I, the two had to flee to Germany; however, she divorced him and returned to Paris after the war. Upon returning, she adopted her new style, painting the thin, willowy, otherworldly female figures with simplified volumes and curvilinear in muted pastel colors, focusing on grays and pinks. She painted portraits and defined theatre and ballet sets, watercolors, and prints.

Jeune Femmes (Young Girls) (7.2.3) was one of Laurencin's first paintings exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911. Her curvilinear lines simplified the geometric shapes, giving the painting graceful lines. She used the darker, muted tones found in early Cubism painting with a small amount of color. Le Bal Elegant, La Danse a la Campagne ( Elegant Ball, Dance in the Country) (7.2.4) was painted a few years later. Laurencin used her traditional lighter and more feminine palette with muted pinks and grays. The shapes are also more fragmented, following the style of Braque and Picasso. The figures have soft edges as the background shapes and lines become straighter and more fractured.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_115_x_146_cm%252C_Moderna_Museet%252C_Stockholm.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=941&height=726)

Les Désguisés (7.2.5) depicts two figures dressed in elegant apparel who appear almost ghostly. The stylized images are rendered in muted colors, the dreamy duo adorned with flowing headdresses. She also added a bird on the head of the seated woman and a bouquet. Laurencin painted the images after returning to Paris from Germany, as new avant-garde ideas began. She still used flat planes of pastel colors giving the painting a look similar to the earlier Cubist works.

In 60 seconds, Assistant Curator Meg Slater recounts the life and work of Parisian artist Marie Laurencin.

Tarsila do Amaral

Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) was from Brazil, the daughter of a wealthy plantation owner. She had the money to travel and study different art movements in Europe. However, she was not as direct in her interpretation of Cubism. Amaral chose abstracted tropical landscapes and portraiture upon her return to Brazil in 1924 after studying in Paris. She blended the techniques of modern European masters, a highly abstract yet very personal representation of the people and land of her native Brazil. She developed a color palette that is significant to Brazilians and different from those in European art. Her work inspired others in Brazil to create artwork unique to their country. After the great depression, her family lost their wealth, and a dictatorial government led her to paint with a more political subject matter.

In her work, Central Railroad of Brazil (7.2.6), Amaral used the Cubist forms to document the modern progress of Brazil, along with the bright colors other modernists used. In the image, Postcard (7.2.7), Amaral displayed her desire to return to working with the bright colors of crayons to depict the city of her homeland. She remembered using crayons as a child and was asked to reject them in art school; however, the vivid colors influenced her oil paint colors. Amaral's painting Abaporu (7.2.8) was one of her new styles to transform European methods into distinctly Brazilian. The background is simple in its form, a small ground hill for the earth, a few green cacti, and the pale blue sky lit by the yellow sun as seen in Brazil. The figure, however, is very distorted. The person is nude, ageless, and sexless. The immense foot and hand anchor the bottom of the painting as the figure grows smaller when moving upward. A small arm supports the head, the face contemplative, sad, bored, or however, a viewer wants to define the emotion.

In her native country, all you need to say is her first name - Tarsila - for people to recognize the woman "the Picasso of Brazil." But Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) is little-known in North America, despite her revolutionary art. Faith Salie visits an exhibition (now showing at New York City's Museum of Modern Art) of Tarsila's "cannibalist" paintings, which took the tropes of Western European art and turned them into something extremely Brazilian.

Natalia Sergeevna Goncharova

Natalia Sergeevna Goncharova (1881-1962) was born in a small Russian town and moved to Moscow as a child. Her father graduated from a well-known Moscow university as an architect and an influence on Goncharova's career. Her great-grandfather was the renowned Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. The whole family was educated and financially successful. Goncharova attended the prestigious Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, initially studying to be a sculptor. At the beginning of the twentieth century, women attending Russian art institutes were no longer segregated; however, they still could not be awarded a diploma when they finished their studies. Goncharova withdrew from the institute and studied in different artists' studios where she could study the nude figure.

Goncharova was part of the more extreme European modern art movements, and she exhibited in the Jack of Diamonds show in 1910. Goncharova and some other Russian artists broke away from the European styles to form their group of modern art, the Donkey's Tail. Their art was considered sinful because some female artists incorporated sacred and irreverent images in their work. It was not acceptable for women to paint religious icons. Goncharova was known for her scandalous public behavior, including living with her male partner, Mikhail Larionov. She wore pants and male shirts, unsuitable for a female. Goncharova and others painted their faces with flowers and walked through the streets bringing art to the ordinary person. Occasionally, she even appeared topless with symbols painted on her body. Goncharova was provocative and said to cross "the boundary of decency and to hurt your eyes."[2] In 1914, she and Larionov moved to Paris, where they married and lived the rest of their lives. Goncharova also was known for her costume designs, especially the Ballets Russes.

Goncharova's work became a basis for Russian Futurism as she incorporated Cubist styles into her work and became known for her Cubo-Futurism. Many Russian artists used dance as a theme in their images to portray folk culture and the incorporation of color. Circular Dance (7.2.9) was Goncharova's depiction of Russian folk women dancing. The scene appears at night with the deep sky color and dark shadows of the houses, trees, and ground. The colorful clothing of the dancers stands out against the dark background. Goncharova used minimal details to create the figures, relying on colors similar to Fauvists. The figures are coarsely rendered, each woman's face visible except the woman in the center with a bright red headdress.

The Cyclist (7.2.9) is painted in Goncharova's Cubist-Futurist style as the cyclist rides over the cobblestone street. Goncharova used the Cubist style of fragmentation to define the concept of speed. She used repeating and dislocating multiple parts to create the image. However, the background names on the buildings remain intact compared to the rest of the image. In the background, a visible finger is pointing in the opposite direction from the cyclist, bringing a clash between the action and movement of the bicycle and the static, reverse solid image of the finger.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=844&height=634)

Discover the art of Natalia Goncharova, the first woman artist of the Russian avant-garde. Her bold and innovative body of work influenced and transcended the art movements of the 20th century.

Lyubov Popova

Lyubov Popova (1889-1924) was from Russia. Her father was a successful merchant and supported the arts giving Popova early exposure to cultural Russia. She was always interested in art and started formal lessons at eleven. By age eighteen, Popova was formally studying art in private studios in Russia and then Paris. Popova became one of the early female artists to develop the Cubo-Futurism style, introducing Cubist and Futurist ideas into Russian art. Throughout the Russian Revolution, Popova worked with other artists to form new types of paintings as part of the revolutionary changes. She incorporated book and theatre design into her portfolio and taught others. Popova married in 1918 and had a son; her husband died a year later from typhoid fever. Popova lived a short life when she died two days after her son, both from scarlet fever.

When Popova was in Paris, she studied Cubism, how objects appeared in the spatial environment, and how they were arranged to create a comprehensible whole. Popova painted several figures, deconstructing the whole and assembling the parts into a unique image. The Model (7.2.11) is an example of how Popova used different-sized parts of the human anatomy and assembled them into the standing figure. She used brown and yellow inside multiple shapes to help define each element. The head of the model is relatively realistic as the torso splits into unusual shapes, sizes, and colors. Each leg and arm are composed contrarily, generating oversized legs and unreal arms. Popova used specific shapes to emphasize the joints, like the shoulders, knees, or elbows. The background is made from parts, generally in grays, softening the background and bringing the figure to the foreground.

In The Pianist (7.2.12), Popova used intersecting, confusing, curved lines, rectilinear planes, and geometric patterns. Her use of lines and planes brings movement to the image of the pianist moving to his music. She mainly used blacks, grays, and whites to depict the player against the rich browns of the piano, almost appearing as wood. The piano keys are flattened against the background as the pianist's fingers play on a different plane, yet the two parts work together.

Mary Harriet Jellett

Mary Harriet Jellett (1897-1944) was born in Dublin, Ireland. Her mother was a musician, and Jellett and her sisters had musical educations. Jellett started her training in art at age eleven and later went to the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin. In art school, Jellett continued her training as a classical pianist believing she would become a professional player. By 1921, Jellett moved to Paris and started exploring abstract art. In Dublin, she exhibited two paintings following the Cubist style and was highly criticized. Jellett became important in Irish art, supporting the new modernist styles while being attacked. IN 1923, the art critic George Russell said of her work that Jellett was "a late victim to Cubism in some sub-section of this artistic malaria and a proponent of subhuman art."[3] However, she continued challenging the Irish art world through exhibitions and lectures. By 1927, the Irish Times was calling Jellett one of the serious modern art painters in Ireland, and now she is touted as the woman who brought modern art to the country. Jellett lived in an Irish Catholic country, and religious concepts can be seen in her abstraction with shapes of altars, religious figures, or halos.

Jellett spent time in Achill, a western Ireland windswept coast location. The region was thought to be dramatic, with pounding beaches and peat-covered hills. She made a series of horse paintings situated in the region. Jellett positioned her horses in Achill Horses (7.2.13) on the hillside; the horses connected to the landscape and each other. Her palette mainly used earthy colors; the exception might be pink in the background. Jellett was a master at using curves to unify the images and link each of the horses with the multiple colors of the landscape. The shading on the two primary horses is carefully delineated, while the other horses in the painting are abstracted.

A Composition – Sea Rhythm (7.2.14) depicts the wild seas surrounding Ireland. Jellett used a color palette of the ocean, from the deepest depths to the shoreline, with waves crashing against the beach. She used curvilinear lines to depict the movement of the ocean. Each area in the painting was different, representing the waves in the ocean. Jellett anchored the image with dark brown like the seabed. Small grains of sand move through the middle of the painting.

[1] Baron, S., Damase, J. (1995). Sonia Delaunay: The Life of an Artist, Harry N. Abrams, p. 20.

[2] Natalia Goncharova – Art in Russia. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20170308...ia-goncharova/

[3] Retrieved from https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-...hocked-ireland