6.5: Impressionism (1874-1886)

- Page ID

- 134999

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Impressionism significantly changed the process of painting, influencing artists around the world. The main passion the Impressionistic artists shared was natural light and color, how the light made colors intense or changed the hue. They also wanted to capture the moment, sitting outside en plein aire and working with quick, dynamic brushstrokes on brushes loaded with paint. The ideas created new concepts of nature and people, and how things portrayed on the canvas formed an impression of a view instead of smoothly blended details. The artists discovered how dark shadows, gray cloudy skies, or deep water fashioned a continual change of colors. Colors brushed with freedom formed lines and contours, making the short, quick brushstrokes recognizable objects. Artists had long painted outdoors, usually sketching partial images and completing them on larger canvases or panels in the studio. The Impressionist artists wanted to work outside and capture a moment in time to exploit the natural light. A few essential inventions facilitated the movement.

The history of the Paris salons and Impressionism were intertwined. The salons held annual shows and only exhibited traditional styles of art. Only a few women consistently exhibited in the salons. When a few adventurous painters tried to submit nontraditional paintings, they were rejected. Some painters worked together and inspired others to try new ideas. From 1874 to 1886, the Impressionists held their shows apart from the Salon and its standards. Critics panned the artwork declaring the colors unblended, with little detail and visible brushstrokes, not artists deserving serious attention. Claude Monet entered the painting Impression Sunrise, and a critic derided the painting as just an impression, not a completed painting, only indistinct and blurry forms. The other artists and Monet started to call themselves Impressionists, and the name remained forever.

During this period in Paris, where the Impressionist movement started, upper-class women were still restricted. Unmarried women needed a chaperone to leave home. Women were expected to learn music, painting, or other arts and find activities performed in the company of other women. The Impressionist style was well suited for women. Traditional art was painted on large canvases and followed heroic or historical themes, concepts defined as unsuitable for women to paint. Impressionists used small-sized canvases with portable easels and paint. Capturing a moment based on natural light allowed women to work quickly. They painted in the garden or made snapshots of commonplace activities by family and friends. The more informal subject matter was easy to observe and complete within their daily domains. Women still faced rejection and were subjected to the demands of their husbands if they married. The artists in this section include:

- Mary Cassatt (1844-1926)

- Berthe Morisot (1841-1895)

- Marie Bracquemond (1840-1916)

- Eva Gonzales (1849-1883)

- Lilla Cabot Perry (1848-1933)

- Louise Catherine Breslau (1856-1927)

Mary Cassatt

Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), born in America, first studied at the Academy of Arts in Pennsylvania before going to Paris to complete her training and travel through Europe, believing art education in America was inadequate. She successfully entered works into the Salon and was critically accepted. Cassatt never married and was independent, free to become very successful and develop a profitable career. In 1877, Edgar Degas, who had seen Cassatt working in the Louvre copying old masters, was captivated by her talent. He invited her to become part of a set of artists called the Impressionists, the only American in the group. Degas became Cassatt's mentor as she changed her techniques, learning new ways to incorporate light and color and developing a specialty painting for women and children. She became a successful Impressionist painter and printmaker, only stopping in the last years of her life because of failing eyesight.

Images of women and children depicted in modern settings, well dressed and fashionable regardless of the activity, became the subject matter for Cassatt's work, a sense of femininity. She focused on children's and adults' relationships and intimate social connections. In most of her paintings of women, Cassatt generally positioned the figure in a diagonal, starting in one upper corner and moving the figure to the reverse corner, stopping around the knees of the subject. "Not only did she make her subjects women, and quite often, women who are not in the presence of men, … in control of their spaces, true to the social realities of the period but not subordinate to the unrealities of academic or allegorical painting."[1]

Afternoon tea was an essential function for the women in the upper or upper-middle classes, part of their daily lives. Cassatt's sister, Lydia, and her mother also lived in Paris, and she used Lydia as a model in many of her paintings, including The Cup of Tea (6.5.1). Cassatt applied brushstrokes and color to form the shadows and shapes of the painting. The soft pinks and white present the feminine image contrasted against the dark stripes of the chair. The well-placed vase of flowers centers the eye; however, the darker blue of the vase blends into the same blue tones of the wall, the painting a balance of complementary colors.

Although Cassatt frequently used relatives in her paintings, she also used different unrelated models, as the two viewed in Young Mother Sewing (6.5.2). The child leans against her mother, who seems undisturbed, continuing her sewing. The girl gazes at the viewer, displaying her boredom and desire to be elsewhere. The woman wears a well-defined striped dress against the color outside the window and a green apron matching the grass. Stripes were a significant theme Cassatt incorporated into her paintings. The vase of orange flowers compliments the softer green. Cassatt's paintings' other motifs are the window opening and the park-like background. The woman who purchased the painting remarked, "Look at that little child that has just thrown herself against her mother's knee, regardless of the result and oblivious to the fact that she could disturb 'her mamma.' And she is quite right; she does not disturb her mother. Mamma simply draws back a bit and continues to sew."[2]

The Loge (6.5.3) depicts a woman dressed for the opera, a popular pastime in Paris and a place to see others and be seen by your peers. Entertainment venues like the theater or racetrack were popular activities for Parisians. Other Impressionists also painted attractive females at the opera, using the opportunity to paint scenes with multiple light styles, all reflecting in the spaces. Cassatt's figure was looking actively through the glasses across the audience instead of pointing her glasses downwards to the stage. A man in the upper part of the painting has turned his view towards her; she has attracted his attention for some reason.

Mary Cassatt, In the Loge, 1878, oil on canvas, 81.28 x 66.04 cm / 32 x 26 inches (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Berthe Morisot

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), born in France, was fortunate to be supported by her family to pursue an art career; her grandfather was Jean-Honore Fragonard, a noted Rococo painter. She copied the old masters found in the Louvre and had one tutor who educated her in the standards of plein aire painting. Morisot associated with Edouard Manet and regularly sent work to the Salon. Critics defined her work as feminine because of her paintings' subject matter and delicacy. She married Manet's brother, Eugene, and had one daughter who became a frequent model in her paintings. Morisot became friends with Degas, who encouraged her to work with other Impressionist artists and enter her work in their first show outside the Salon. Often seen as a pioneer to be the first female exhibiting in the Impressionist show, such was her standing that Degas declared: "We think Berthe Morisot's name and talent are too important for us to do without."[3]

The Cradle (6.5.4) depicts Morisot's sister sitting by the cradle with her daughter, Morisot's first portrayal of motherhood, a subject she frequently used in later paintings. The contemplative look on the mother's face, the positioning of her arms, and her soft expression all demonstrate a feeling of intimacy between a mother and child. Morisot uses her characteristic feathery brushstrokes of white and gray accented with pinks, blues, and lavender. Her first painting in the new Impressionist exhibit was not considered a critical success, only defined as elegant.

The Impressionists held eight shows of their work; Morisot exhibited Lady at Her Toilette (6.5.5) in the fifth show, a painting positively received by the critics. Morisot used soft, delicate brushstrokes, portraying intimacy with muted shades of pink, blue, and lavender swirling around white and gray. The painting was considered erotic, an emotion frequently pursued by male artists and seldom approached by female artists. Although the images in the painting are delicately developed, a sense of voyeurism is also created. The woman is unaware of the people viewing her in the mirror, a woman in the privacy of her bath.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Lady at Her Toilette (1875-1880, oil on canvas, 60.3 x 80.4 cm) (Public Domain)

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Lady at Her Toilette (1875-1880, oil on canvas, 60.3 x 80.4 cm) (Public Domain)Gloria Groom, curator of the exhibition Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, takes you on a tour of one of the Berthe Morisot's masterpieces.

Summer Day (6.5.6) portrays two women floating on the lake, each looking in a different direction, contemplating their thoughts. It was acceptable for women to walk along a pathway or picnic in the park; therefore, Morisot could set up her easel in this standard location. She could not sit at an easel and paint the corner café or city streets as her male counterparts did. Morisot used her typical feathery strokes to capture the light on the water, the swimming swans, and the reflections of the plants on the bank. Critics of the time felt the work was too sloppy and unfinished.

The most striking feature of the principal painting stage is Morisot's unique and unmistakable brushwork, much commented upon by her contemporaries. Its repeated zigzags give the image a shimmering, restless quality, as if the entire scene were refracted through countless prisms. This effect unifies everything into one continuous sweep of texture and color: figures, background, and water merge into a bright blond tonality that ripples across the whole picture surface. Individual forms are almost submerged in the decorative patterning of the paint.[4]

Marie Bracquemond

Marie Bracquemond (1840-1916) married Felix Bracquemond, a lithographer who worked with many early Impressionist artists. Marie was a painter who followed the ideals of Impressionism, and some believe she created far more exciting paintings. Historians have noted the support their son gave to Marie and the jealousy of the father, Felix. Marie Bracquemond often acted as a hermit; most paintings were created in her garden. Even though her husband disapproved of her art, she defended Impressionism throughout her lifetime, stating, "Impressionism has produced…not only a new but a beneficial way of looking at things. It is as though all at once a window opens, and the sun and air enter your house in torrents."[5] The Artist's Son and Sister in the Garden at Sevres (6.5.7) is Bracquemond's son and sister, who was a standard model for her paintings. The white dress with highlights of blue and pink and dotted with dark spots, spills everywhere, almost dominating the painting. The red blots of flowers form an encircling background to set off the figures, the son's white vest moving the eye from person to person.

Eva Gonzales

Born in Paris, Eva Gonzales (1849-1883) was educated in the artistic circles her father participated in and began training as an artist at age sixteen. She soon became a student of Manet and a model for many Impressionist artists. The basic style Gonzales learned under Manet remained the same throughout her life, based on concepts from ordinary people and how they lived, frequently using her family members as models. Gonzales often worked with pastels to keep her colors and contours softer with a lighter palette. Although the reviewers of the Salon felt she demonstrated outstanding technical skills, her work was defined as a 'female technique.'. Gonzales died in childbirth when she was only thirty-four years old.

Jeanne, Gonzales's sister, is depicted in Morning Awakening (6.5.8), an early morning scene, not quite awake. The image defines a second in time, one of the standards of the Impressionists, along with using the effects of light shining through the window. The image was cropped, only the top part of her sister, bringing the viewer into the bedroom scene. Gonzales used various blues, greys, pastel pinks, and violet, highlighting the white clothing, gossamer bedding, and curtains.

Lilla Cabot Perry

Lilla Cabot Perry (1848-1933) was the eldest of her family's eight children and was born in Massachusetts. As part of the illustrious Cabot family, her family was well-known in Boston society. From an early age and as a child of privilege, Perry studied literature, music, and art. In her early twenties, she married Thomas Perry, who was also from a well-known family. They had three daughters. Perry was able to start formal art training in 1884 when her father died a year later and left her a significant inheritance. With the money, she and her family traveled to Paris, where Perry studied for two years. She became friends with other Impressionists, especially Claude Monet and Camille Pizzaro. For the next ten years, the family stayed at Giverny near Monet in the summer to visit and illicit his advice on her artwork.

The ideas of Impressionism were introduced in America, and Perry began supporting the French artists and the other American Impressionist, Mary Cassatt. Perry organized art exhibitions based on the Impressionist style and displayed her works at the shows. Perry became a prolific artist and exhibited her work in major American cities and Paris. She demonstrated her diversity by painting landscapes and portraits. She successfully gained acceptance for her art and acknowledgment of the new type of painting. Perry's paintings of women were delicate and airy. She used family members as models, especially her daughters and their pets.

Lady with a Bowl of Violets (6.5.9) demonstrates Perry's Impressionist style with light-infused colors applied with visible brushstrokes to develop the colors. She had been to Tokyo and studied Japanese woodblocks. Perry incorporated a woodblock print in the background on one side of the painting and flowers on the other. Most of the plain background incorporates hues of blue and yellow, the colors repeated in the woman's clothing in contrasting positions. Perry's loose brushstrokes create the woman's skin texture and the lace trimming on her dress. The glow from the fireplace is reflected on the wall by orange highlights. Light from the window bathes the left side of the figure. Child at the Window (6.5.10) is an image of Perry's daughter. The scene might be in southern France or the United States, demonstrating Perry's love of Impressionism. The heavy, broad brushstrokes are evident throughout the painting. Using quick strokes of multiple paint colors and the light shining in the window, Perry developed the girl's dress without the realistic applications from the past. The vegetation was painted with unique brushstrokes to form each leaf. The broad window brought light into the room and onto the girl as the background in the window diminished into a hazy glow.

Louise Catherine Breslau

Louise Catherine Breslau (1856-1927) was born in Germany; her parents were of Polish Jewish descent. As a child, her family moved to Switzerland, where her father taught at the university. Breslau's father died when she was only ten years old. Because she had chronic asthma, Breslau was sent to live in a convent for care and education. Young women were expected to learn how to draw and play the piano, suitable attributes for becoming a wife. Breslau had a talent for art and knew she needed to leave to study art seriously. The Académie Julian in Paris was one of the few places a young woman could study art as a career. Breslau befriended Madeleine Zillhardt at the academy, who became Breslau's lifelong partner. The academy was also the only school to allow women to draw nude models. Breslau was an outstanding student and successfully exhibited her art at one of the salons and opened her studio. Her reputation grew, and she was a prosperous artist with many commissions from wealthy patrons. Breslau became the first foreign female artist to receive the French Legion of Honor award. Although Breslau did not think of herself as one of the Impressionist painters, she did adopt their styles, especially with her brushwork.

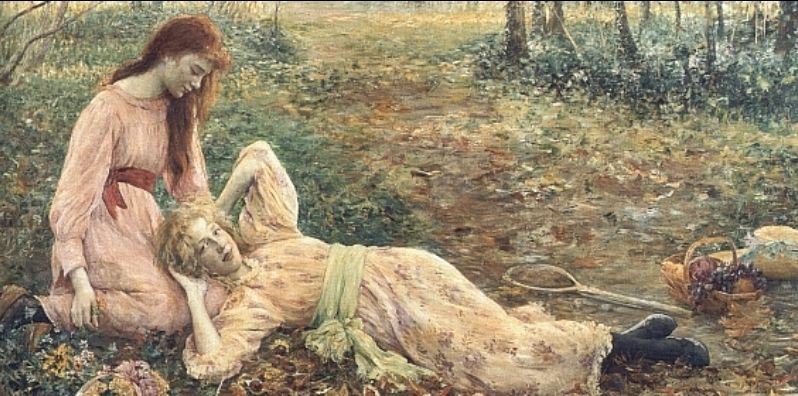

Gamine is the feminine form of the French gamin, meaning a wayward or naughty child. In the painting Gamines (6.5.11), tennis rackets lay on the ground near the two young girls. Women had to play games like tennis, still appropriately attired in long dresses and leather shoes with heels. The poses of the two girls appear romantic as one tenderly looks down on the other girl. Breslau used muted and limited colors in the painting. The scene is set with a brown pathway and green shrubs and trees. The girls wear dresses on the same color spectrum of oranges and yellows, their sashes contrasting. The quick, short Impressionist brushstrokes are evident throughout the painting. La Toilette (6.5.12) was a common theme for female artists to paint. The images were always intimate and personal and generally based on how a family member or friend dressed. Breslau captures this woman as she is fixing her hair. The person is in her night clothes, and the light from outside into the room is diminished. It is hard to define if the woman is getting ready for bed or if it is early morning and she has just risen. Breslau leaves the puzzle for the viewer to decide. Using the same muted colors and quick, thick brushstrokes, Breslau defines the woman's body, clothing, drapery, chair, and table covering. Each element is apparent even though the same colors are used, a mastery of the Impressionist style.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.radford.edu/rbarris/Women%20and%20art/amerwom05/marycassatt.html

[2] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10425?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=Mary+Cassatt&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=11

[3] Spence, R. (2012, May 1). Berthe Morisot, Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris. Financial Times.

Retrieved from https://colourlex.com/project/morisot-summers-day/

[4] Bomford D, Kirby J, Leighton, J., Roy A. (1990) Art in the Making: Impressionism. National Gallery Publications, London, pp. 176-181.

[5] Gaze, D. (2013). Concise Dictionary of Women Artists, Routledge, p. 206.