4.4: Asian Landscapes (Late 1500s – 1700)

- Page ID

- 134986

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

The Manchus were a people who originated from Northeast Asia. In 1644, they established the Qing Dynasty, the last of the great imperial dynasties in China. Under the Manchus, art in China underwent significant changes as the new rulers brought with them their cultural traditions. Blended with Chinese traditions, they created a distinctive form of art still celebrated today. Under the Manchus, the art of calligraphy underwent significant changes. Calligraphy had long been a revered art form in China, but a new style known as “running script” emerged during the Qing Dynasty. This style was characterized by a more fluid, cursive approach to writing, in contrast to the more rigid types dominated in previous eras. Running script calligraphy was popular among the literati and the general public, and it played a significant role in shaping the era's aesthetics.

Finally, the Manchu rulers were patrons of the arts and played a significant role in the development of art under their reign. The Kangxi Emperor, who ruled from 1661 to 1722, was particularly interested in the arts, and he is credited with having established a new style of painting known as the “Kangxi Landscape.” This style was characterized by a more naturalistic approach to painting, with a greater emphasis on realism and detail. The Kangxi Emperor was also a ceramics patron, and his reign saw the development of new techniques and styles in this field. The Manchu Dynasty significantly impacted the development of art in China. The new rulers brought their cultural traditions, which blended with Chinese customs. Today, art from the Qing Dynasty is celebrated for its beauty, innovation, and role in shaping China's cultural identity.

During the Ming and Qing periods, increased wealth and the widespread use of printing enhanced the literacy of men and women of high rank. The period also gave rise to the courtesans, women who were well-educated and entertained men. The women were known for their painting skills and ability to write poetry. After completing a painting, the artist also wrote a poem to add a definition of the image. Other female artists were from families of artists and learned from their fathers or grandfathers. Today, researchers can only rely on surviving artwork to understand what was produced and the styles of art created by female artists. Although women artists are frequently divided into "courtesan painting" and "gentry women painting," their work was similar and indistinguishable from female painters of any class. It was permissible for women to paint; however, they could not publicly circulate their art.[1]

Women were not constrained to any genre style; however, women generally painted flowers and birds, called Bird-and-flower painting. Women artists may have painted the genre because they found inspiration in nearby gardens. The garden was part of the home and, therefore, always accessible for viewing. They also tended to use similar brushstrokes and compositional themes using conservative methods. Perhaps female artists were not exposed to the art world in general and different or new methods accessible to men. Female artists in the Western world were constrained from studying or painting the nudes male artists did. However, this was not a problem in China because neither sex painted nudes.

For painting and calligraphy, artists traditionally used four basic types of equipment; paper, brushes, ink, and inkstone. The ink was made into a cake. The artist ground some of the ink onto the inkstone with a small amount of water. The ink the artist puts on the brush depends on the artist's drawing. Black ink cakes were generally made of carbonized pinewood or oil soot, mixed with glue, pounded, shaped, and dried. Colored pigments were made from natural plants or minerals and mixed with glue. The bond allowed the pigments to bind to the paper or silk. Brushes were generally made with deer, goat, or rabbit hairs and were very pliable. A painter used techniques similar to calligraphy, with the brush as a tool dipped into colored pigments or black ink and manipulated to form delicate line structures.

Solid ink sticks are the go-tos for painters in China, but to make them, artisans must spend more than a year collecting ash, pounding, molding, and painting each bar by hand. This laborious process means many think ink sticks are more precious than gold. We visited a master in Anhui province to see how they are made.

This is a beginner's video explaining how to use the ink. The sumi ink stick is used for Japanese calligraphy, illustration, or other artwork.

Artists in Asian Landscapes:

- Ma Shouzhen (1548-1604)

- Qiu Zhu (1565-1585)

- Wen Shu (1595-1634)

- Xue Susu (1564-1634)

- Yun Bing (unknown)

- Ma Quan (unknown)

- Li Yin (1610-1685)

- Shin Saimdang (1504-1551)

- Heo Nanseolheon (1563-1589)

Ma Shouzhen

Ma Shouzhen (1548-1604) was born in Nanjing in the later part of the Ming dynasty. She spent her life as a courtesan and lived in the entertainment district where many courtesans practiced their trade. Ma was considered an elite courtesan and taught other young women how to become proper courtesans. An elite courtesan was a complete artist and well-trained in poetry, calligraphy, and painting. Because of her status, Ma only accepted men who were educated or one of the young lords into her residence. The style name she received as an adult was Ma Xiangian (Orchid of the Xiang River) because the paintings she liked the most were those of orchids. During the Ming dynasty, women were supposed to be wives and mothers, and the use of any talents was discouraged. However, courtesans were expressly educated in painting, writing, and music. They were also able to own property. Ma was educated as a courtesan at an early age and was exposed to multiple writers, poets, and other artists, and she learned to write poems.

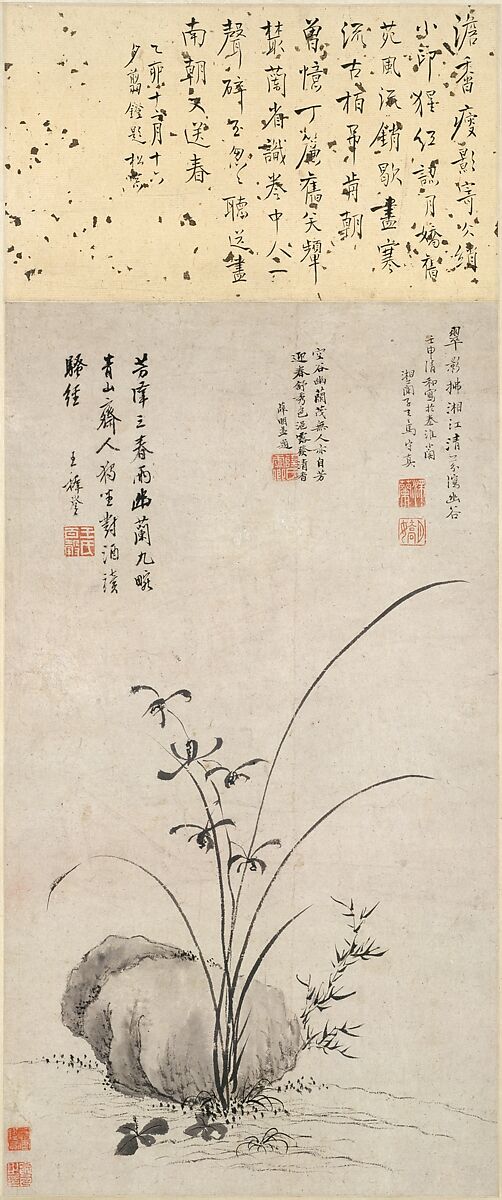

Ma was a prolific painter known for her landscapes and images of orchids and bamboo. Because she loved writing and poetry, Ma included extensive calligraphy in her paintings. She preferred working on scrolls or fan shapes. Although she created multiple works of art, little has survived today. Orchid and Rock (4.4.1) are painted on a scroll with her usual delicate brushwork. Ma used a monochromatic color palette, with the finely-inked orchid plant growing right next to the oversized rock. The rock's solid appearance anchors the plant's delicate flowers and leaves. On the upper right-hand side, the inscription reads:

Deep green shadows are cast onto the Xiang River; Pure aroma fills the secluded valley.[2]

Other artists or collectors who came in contact with the painting also added red seals to the scroll, a typical Chinese custom.

Qiu Zhu

Qiu Zhu (1565-1585) was Qiu Ying's daughter, considered one of the four masters during the Ming dynasty. It is generally assumed Qiu Zhu learned her painting skills from her father. Although she used firm brushstrokes, her drawings were very delicate and ethereal. Qiu was a successful artist with commissions for paintings. She also provided the image as part of a poet's writing, a collaboration of a poet and painter. In most of Qiu's paintings, she focused on a figure instead of the usual pure landscape. The goddess Guanyin was one of her favorite subjects. Guanyin was considered the bodhisattva of compassion, a figure of interest to women. Qiu created a series of twenty-four portraits in an album portraying Guanyin along with text passages.

Qiu painted women in different activities, as seen in Painting of Women Playing Musical Instruments (4.4.2). One woman in the background is arranging flowers while others are playing instruments, seated on a carpet. The wall in the background and the yard indicate the women are nobles and safe in their own space. The decorative roof over the door, a tree, and some women's clothing are all painted bright green and stand out against the monochromatic, dark background. At the top of the painting are the inspirational words accompanying the image. In Inspired by a Tang Poet (4.4.3), Qiu used much lighter colors based on a similar color palette. The woman is anchored at the bottom of the painting and becomes the focal point. Qui balanced the figure with the flowers, trees, and rocks. Qiu used red as the accent color in this painting; the greens pushed to the background.

Wen Shu (Wen Chu)

Wen Shu (Wen Chu) (1595-1634) used Hanshan and was considered a master painter of flowers and insects. Her great-grandfather and father were painters, and Wen learned to paint early. Wen married one of her father's students, and they only had one daughter. They adopted one of his cousins as their son to continue her husband's male line. Wen was a respected artist and earned money as a tutor to noble girls and married women. Although landscape painting was considered an unsuitable subject for women, Wen Shu chose flowers and wildlife for her paintings. Flowers were becoming a viable commercial subject matter for artists. Because most of Wen's work has no poetry or dedications, most historians believe her work was created for a commercial audience.

Wen Shu usually used a simple background allowing the subject to stand out. In Hua Niao Tu: Painting of Flowers and Bird (4.4.4), the scene is quiet, muted, a peaceful feeling. The background is made with a mogu style, a wash of ink, and color without outlines. Wen carefully blended the colors into a semi-cloud atmosphere. Against the background, the branch, leaves, and birds stand out. The images are very detailed, and the veins on the leaves and delicate white flowers are noticeable. The bird is carefully painted, and each feather seems to be visible. Wen used the branch to tie the images together.

Xue Susu (Xue Wu)

Xue Susu (Xue Wu) (1564-1634) spent most of her childhood in Beijing and her adult life in Nanjing before returning to Beijing. Xue was highly accomplished in the skills of a courtesan and was well known as a painter and poet, an expert in xiao (bamboo flute) and weiqi (a board game). She also was skilled in mounted archery, an unusual talent for a woman. At many of her parties, Xue gave archery performances to the public earning her the nickname of a female knight-errant. Poets even wrote poems about her skills as an archer. One poet wrote, "While she gallops on horseback, she shoots two balls from the crossbow, making the first ball hit the second in the air…she never misses one such shot in a hundred."[3] Xue studied military activities and tried to influence different events. Xue was married multiple times, her marriages never lasting very long or producing any children. Later in her life, Xue became a Buddhist, remained unmarried, and left the courtesan life.

Xue was a talented painter as a teenager, and one of her paintings was considered "the most accomplished work of its kind in the whole of the Ming period." Her brushwork was "vigorous and forceful," and she was called "a master of technique."[4] Xue was known for her work with traditional objects of bamboo, flowers, and landscapes. Xue incorporated multiple elements in Lan Zhu Song Mei Tu (Orchid, Bamboo, Pine, and Plum) (4.4.5). The short dramatic leaves of bamboo fill one side of the painting, balanced by the long, thin leaves of the orchid. Xue used black ink without color to create the images, applying different amounts of ink and pressure to achieve the shaded gray look. The background was carefully applied ink using the mogu brush style and creating gradations of tones. Xue was also known for her figure painting, an uncommon topic for female painters and similar to the subject matter for male painters. Beautiful Woman in Plain Lines (4.4.6) depicts the woman working on her painting. Xue used delicate, fine lines to draw the clothing with detailed patterns demonstrating her mastery of brushstrokes. The vase on the table holds two peacock feathers. During the Ming dynasty, the peacock represented power and beauty, and the eyes on the feathers were related to the goddess Guanyin.

Yun Bing

Yun Bing (unknown) was born in Changzhou. Her family had many talented artists, including her grandfather, who founded a school and was considered a master of the mogu style. The style became a symbol for the artists in the family, including Yun Bing. The Yun family was well documented in the family genealogy book, noting some of the artists. Yun Bing married and sold her paintings and poetry to help support the family.

Yun's artistic style followed the family's use of the mogu method in her bird-and-flower paintings. She used strong lines to define the outlines of petals or leaves. Yun carefully studied the flowers, grass, and insects around her home to develop her inspiration from nature. She wanted to understand how the light reflected on the top and bottom of leaves and their shapes to obtain a three-dimensional look. Both her paintings of Flower Study (4.4.7, 4.4.8) demonstrate her attention to the leaves. Every leaf is perfectly shaped, with fine lines illustrating each leaf's veins. Some parts of the leaves are darker depending on the light or shading of another leaf or a flower. Yun used a muted palette in both paintings, except for the red image.

Ma Quan

Ma Quan (unknown) remains relatively unknown; however, some information suggests Ma was from Changshu. Historians believe her father or grandfather was a well-known artist. After Ma was married, she sold paintings to add to the family income and taught other students. Her work became popular, and Ma had others formulate her paint, allowing her to create more works to sell. Unfortunately, in later life, Ma became blind and could no longer paint. Ma painted the bird-and-flower genre and liked to include those elements in the typical garden.

Flowers and Butterflies (4.4.9) is a section of the handscroll filled with butterflies flitting around the flowers. Most of the colors Ma used on her palette are light and pastel against the light background. The muted colors on some background butterflies and flowers strongly contrast with the darker butterflies in the foreground. Ma was known for the precise lines seen on each of the butterflies. Each one has a different pattern demonstrating her skill with the brush. The White Head's Honor and Glory (4.4.10) contrast Ma's light palette in her other painting. This painting has a dark background making it harder to see the two birds in the tree. Ma used white and pink for the detailed, small flowers in the tree, with the larger roses anchoring the bottom half of the painting. Ma created a landscape with roses so close one might smell them. The cliff and trees appear farther from the flowers, yet the birds are in the foreground. The rocks near the bottom bring depth as they seem far away.

Li Yin

Li Yin (1610-1685) was born in Zhejiang with little information about her family. Some researchers believe she studied poetry and painting early in her life, although the family had little money. Li became a courtesan and was able to learn art from well-known teachers. Li's talent was recognized as a teenager, and a court official, Ge Zhengqi, married Li as a concubine. Ge was also an artist; they painted and wrote calligraphy early on. Because he worked as a court official, they traveled on imperial business, and Li wrote poetry and painted the sights of her travels. After Li's husband died, she sold paintings to support herself for forty years. Li's paintings of flowers and birds were so famous her works became a souvenir for visitors to her home city. Li gained a reputation as one of the finest female painters.

Li preferred to paint flowers and birds using ink she applied directly to the paper or silk with freehand brushwork. The Lotus flower has long been a divine symbol and a frequent element in Asian paintings. Li used the lotus flower in Lotus Flowers and Birds (4.4.11), demonstrating the elegance and beauty the flower represents. She created a white flower in the middle of the painting with more muted pink flowers on top. The large lotus leaves are perfectly painted, exhibiting Li's skill with free-flowing inks. The leaves are large and folded, and Li masterfully colored the bottoms and tops with different tones. The birds stand on thin, long legs, each bird in a different pose and activity. In Pines and Eagle (4.4.12), the eagle is perched on a branch in the middle of the painting; its head swiveled around. The wing seems almost ready for flight, and the tail feathers are tucked downward. Li positioned the bird in a manner open for interpretation, leaving the viewer to wonder if the bird is startled or threatening an invader. The pine branch flows through most of the painting and is covered with delicate needles. The painting demonstrates Li's ability to freely use her brush and ink to make fine lines or dramatic poses.

Shin Saimdang

Shin Saimdang (1504-1551) lived during the 500-year Joseon period at her maternal grandmother's home. Her father was a government official and frequently lived elsewhere. Because Saimdang, her mother, and her sisters continued to live with their grandparents, Saimdang was educated by her grandfather with the same skills as a male child. She was exceptionally talented and skilled in calligraphy, embroidery, writing, and painting. Saimdang married at nineteen and had to travel with her husband to different places as part of his governmental position. They also had eight children. One of the sons became a well-known Korean Confucian scholar who, along with Saimdang, appears on a current Korean banknote. Ironically, Saimdang's real name is unknown. Sometimes she was called Shin In-seon; however, no record of her name exists in history.[5] The name Shin Saimdang is a pen name she used.

Saimdang paintings were based on elements of nature, flowers, insects, fish, and landscapes. Her work was known for the delicacy of her brushstrokes and the use of ink and colors. Saimdang painted eight panels for a folding screen using illustrations reminiscent of her garden. Her Chochungdo (grass and insect) paintings were very detailed and selected the insect and plant combinations for the seasons they appeared together. Of the eight panels, the two Chochungdo panels (4.4.13, 4.4.14) are painted in vibrant colors. Each leaf on a plant is carefully rendered depending on how the leaf is folded. Less than forty paintings are associated with Saimdang because they are difficult to trace. As a woman, she did not have a seal or any signature. Historians believe Saimdang created many more paintings that cannot be directly attributed to her. One official said, "Under the Confucian society, her best value was producing Yi I, one of the greatest scholars of the time."[6] Today Saimdang is one of the best-known artists and writers in Korean history.

Shin Saimdang 신사임당 (1504-1551) was a Korean artist, writer, poet, and calligraphist born in the Joseon dynasty 조선시대 (1392-1897).

Heo Nanseolheon (Heo Cho-hui)

Heo Nanseolheon (Heo Cho-hui) (1563-1589) was born into a well-known political family of distinguished scholars. Her father had multiple children with his two wives; Nanseolheon was the daughter of his second wife, a daughter of a political family. Nanseolheon's father strongly believed in the Confucian concept of Namjon Yubi (Men are honored, but women are abased). Women were incompetent and inferior to men and severely restricted outside the home.[7] From an early age, Nanseolheon was known as a gifted child in poetry and art. Her brother was the only one who encouraged and supported her and obtained a tutor. She married at age fifteen, an unhappy marriage as her husband continued to have relations with other women. Nanseolheon had two children who died as infants, and she died at the early age of twenty-seven.

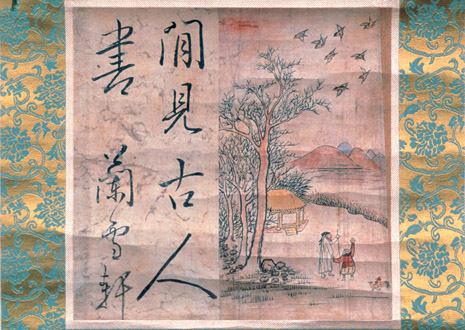

Historians have yet to learn exactly when she wrote and painted. However, her early work was about nature and folklore, and her later work lamented the circumstances and suffering of women. After Nanseolheon died, her older brother ordered her work to be burned. One of her younger brothers kept most of her poems and later published them. Although Nanseolheon was best known for her poetry, she was also considered an accomplished painter. Anganbigeumdo (4.4.15) depicts a girl watching a flock of birds in the sky. At the time, girls were never drawn in paintings, and perhaps this girl demonstrates Nanseolheon's frustration with a woman's place in society. The girl waves to the birds, admiring their freedom. Much of her work was destroyed after her death; however, this painting was thought to be kept by her younger brother. The dense, hard brushwork strokes may reflect her feelings and sorrow at her position as a woman.

[1] Retrieved from https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.ed...46a3fd/content

[2] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/48932

[3] Retrieved from https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.ed...46a3fd/content

[4] Victoria B. Cass (1999). Dangerous women: warriors, grannies, and geishas of the Ming. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 39 Retrieved fromhttps://archive.org/details/dang...ge/38/mode/2up

[5] Retrieved from https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art...91_225097.html

[6] Retrieved from https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art...7/03/691_22509

[7] Retrieved from https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:...31/metadc3987/