2.3: Women Artists in Early Art (5000 BCE - 1000 BCE)

- Page ID

- 201449

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Egyptian

It's important to recognize that women have played a vital part in the evolution of jewelry and metalworking throughout history. Their contributions have been invaluable and continue to inspire new generations of artisans and designers in these fields. In many ancient cultures, women were skilled in metalworking and created intricate jewelry and decorative objects. For example, in ancient Egypt, women were responsible for creating detailed gold and silver jewelry, often buried with the dead as a form of wealth and status. The art of ancient Egypt is perhaps one of the most well-known and iconic examples of ancient world art. The ancient Egyptians created a vast array of art, from monumental sculptures and reliefs to intricate jewelry and pottery. One of the most famous examples of ancient Egyptian art is the Great Sphinx of Giza, which dates back to around 2500 BCE. This massive sculpture, which stands over 20 meters tall, depicts a lion with the head of a pharaoh and is thought to have been built to guard the pyramids of Giza.

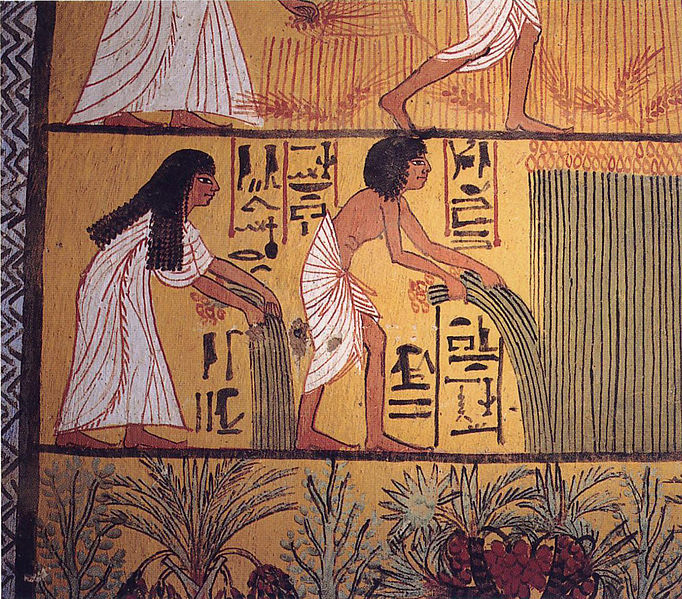

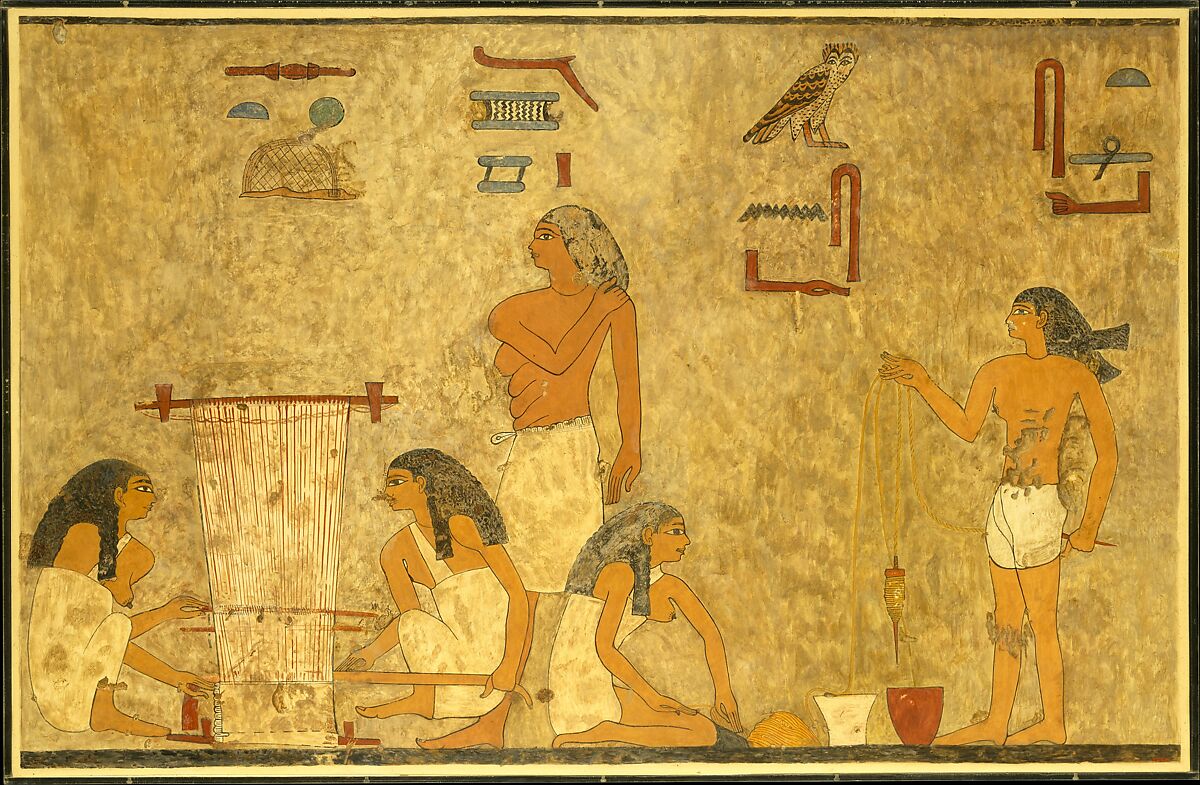

Women in Egypt had legal equality back to 2750 BCE and could own property, sign documents, and leave their property to whoever they wanted. As a fully legal people, Egyptians had more rights than women in the US in 1950. They wove baskets, ground up rock for paint, and were even boat pilots. Most house chores, like making bread every morning, were up to women. Egyptian women were essential in producing linen, a staple fabric in ancient Egypt. Making linen (2.3.1) involved several stages, from planting and harvesting flax to spinning threads and weaving cloth. Women were involved in almost every step of the process, from planting the flax to weaving the final product. All of these factors provide a glimpse into the significant contributions and rights that women in ancient Egypt held.

The process of growing flax involved several tasks such as soil preparation, seed planting, and plant care. When the flax plants reached maturity, the harvest involved physically pulling them out of the ground by their roots. This was a demanding process that required significant physical effort. Following the harvest, the women separated the fibers from the rest of the plant by soaking the flax in water and then beating it with a wooden flail. The fibers were then combed to remove any remaining debris.

Once the fibers were cleaned and prepared, women spun them into thread. This was done using a spindle, a simple tool made of wood or bone that allowed the fibers to be twisted into thread. Spinning was a time-consuming process that required a lot of skill and practice. Once the thread was spun, women wove the thread into cloth. This was typically done on a vertical ground loom, a simple frame made of wood or bamboo. The warp threads were tied to the loom, and the weft threads were woven in and out of them to create the cloth. Weaving was a complex process requiring much precision and attention to detail.

The production of linen was an essential part of ancient Egyptian society, and it was used for various purposes, including clothing, bedding, and even mummification. Linen was highly valued for its strength, durability, and coolness, making it ideal for Egypt's hot and dry climate. The role of women in the production of linen was essential to the economy and society of ancient Egypt. Women were responsible for almost every stage, from planting the flax (2.3.2) to weaving the final product. This gave them an essential role in the household economy and the broader economy of Egypt.

Women in ancient Egypt were not just limited to producing linen. They played important roles in society, such as managing households, raising children, and serving as priestesses and healers. Although their rights and opportunities were restricted in comparison to men, their contributions were highly valued. The weaving of linen was a crucial aspect of the ancient Egyptian economy and society, and women played an indispensable role in every stage of production, from planting and harvesting flax to spinning and weaving. Their expertise and contributions were vital to the production of this essential fabric.

Nubian

The Nubian women of Sudan have a long and distinguished history of crafting breathtaking ceramic pots (2.3.3) are made using techniques passed down through generations and play a significant role in Nubian culture and daily life. Nubian ceramic pots are used for storing and are both intricate and ornate. The techniques used in the creation of these pots have been passed down from generation to generation, and they hold a significant place in Nubian culture and daily life. The pots are used as containers for carrying and storing water, food, and other essential items, and they are embellished with complex patterns and designs that hold deep cultural and spiritual meaning.

Nubian women's exceptional talent and artistry in crafting these pots has earned them recognition and admiration both locally and globally. Their contributions to the cultural legacy of the Nubian community have been brought to the forefront, highlighting their resilience in the face of obstacles such as limited access to resources and materials. Despite these challenges, the practice of Nubian ceramic pottery continues to thrive and remains an integral part of the community's cultural identity.

Nubian pottery is a unique form of ceramics developed by women in the Nile Valley region of northern Sudan. For centuries, Nubian women have created beautiful and functional pottery using traditional techniques passed down from generation to generation. The Nubian people are an ancient African civilization living in the Nile Valley region for thousands of years. Nubian pottery reflects the rich cultural heritage of the Nubian people and is an integral part of their cultural identity.

The exquisite craft of Nubian pottery making involves the careful selection of clay from the riverbanks and nearby areas. The clay is then artfully mixed with water and shaped into various forms using traditional techniques, such as coiling, pinching, and slab-building. To achieve its final form, the pottery is fired in a kiln to harden and strengthen it. The remarkable tradition of Nubian pottery has been passed down from generation to generation, with women being the primary producers of these exquisite pieces of art. Their exceptional skills and expertise have been honed over the years, often working together in small groups to share their knowledge and skills, creating a sense of profound community and sisterhood.

Nubian pottery boasts a unique characteristic in its ornamental designs. The intricate patterns are crafted using diverse techniques, including incising, carving, and painting. These designs mirror the natural environment of the region, showcasing the plants, animals, and landscapes surrounding the Nubian community. However, Nubian pottery is more than just a work of art, as it serves practical purposes such as cooking, storage, and transportation. These pots are often sold at local markets and are a vital source of income for many Nubian women. Nonetheless, the production of Nubian pottery is not without its challenges, as these women often face limited resources, market access, and low product prices. Despite these difficulties, many Nubian women continue to create exquisite pottery and uphold their cultural heritage.

Nubian pottery is a basic form of ceramics developed and produced by women in northern Sudan for centuries. It reflects the Nubian people's rich cultural heritage and is essential to their cultural identity. Women have played a central role in producing Nubian pottery, sharing their skills and expertise, and creating a sense of community and sisterhood. While there are challenges facing the production of Nubian pottery, it continues to be an important source of income for many women and an essential part of the cultural landscape of northern Sudan. The resurgence of interest in Nubian pottery and its cultural significance has been a source of inspiration. The Sudanese Women's Development Organization has been instrumental in empowering women to create beautiful pottery and providing them with the resources and means to sell their products. Thanks to the growth of tourism, Nubian women are now able to showcase their creations to a wider audience and share their unique cultural heritage with the world.

Greece

During the classical period (approximately 800 BCE to 500 CE), women persisted in creating art in diverse forms. The Greek society of that era was known for its patriarchal tendencies, where men held most of the power, and women were restricted to the domestic sphere. Nonetheless, some women challenged these societal conventions and made noteworthy contributions to the art world. Despite their limited opportunities, these women defied societal norms and left a significant impact on the world of art. Their artistic endeavors have sparked inspiration for generations of artists, and their legacy continues to influence the art world even today.

Women were involved in creating pottery, textiles, and other decorative arts. However, their contributions were often overshadowed by the work of male artists and philosophers. Despite this, some notable female artists emerged during this period, such as the poet Sappho and the painter Irene of Athens. However, their work has often been lost or overlooked due to the patriarchal nature of ancient Greek society.

A woman's position in the ancient world was generally well-defined, placing them in positions to support men, bear children, and maintain the household. The concept of art and artists were a term usually reserved for men. In Classical Greece, the average woman cared for their children, managed the family, and wove the fabric. They had some mobility and capabilities to socialize when gathering water at the well or attending festivals. Despite the defined and restrictive roles for Greco-Roman women, the Greeks worshipped powerful goddesses, a phenomenon unavailable to later Christian women. Although there were women artists, they seldom signed their names or otherwise identified their work. However, Pliny the Elder, who documented his view of the world in his treatise on Natural History, identified several female artists as part of his chapters on art history.[1]

The artists included are:

- Timarete (or Thamyris) (5th C. BCE)

- Irene (5th century BCE)

- Myrtis (5th century BCE)

- Sappho (6th century BCE)

- Phryne (4th century BCE)

- Aristarete (6th century BCE)

- Eirene (6th century BCE)

- Iaia of Cyzicus (116-27 BCE)

- Helena of Egypt (probably 4th century BCE)

Timarete and Irene

It is believed that Timarete (5th C. BCE) (also known as Thamyris) was the daughter of the painter Micon the Younger, who inspired her to pursue art instead of traditional women's work. According to Pliny the Elder, Timarete was known for her paintings of the goddess Diana at Ephesus. Another female painter, Irene, was also recognized as the daughter and student of the artist Cratinus. Her artwork included depictions of an elderly man, a young girl, and a juggler named Theodorus, but she was especially renowned for her paintings of the goddess Athena, which received high praise from her contemporaries.

Myrtis

Myrtis, an extraordinary female artist, is known to have lived in ancient Greece during the 5th century BCE. Her poetic prowess was exceptional, and she was highly regarded for her elegies and epigrams. Typically, her compositions were dedicated to honoring the deceased, and their quality was widely admired by those who knew her. Despite her remarkable artistic achievements, little is known about her personal life.

Sappho

Sappho, a renowned poet who lived during the 6th century BCE in Greece, is widely recognized as one of the most influential figures in the world of art. Her lyric poetry, which was characterized by its emotional depth and romantic themes of love and desire, continues to captivate readers and inspire countless poets to this day. Sappho's contributions to the world of literature have left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape, and her legacy is a testament to the power of creative expression.

Phryne

During the 4th century BCE, a sculptor by the name of Phryne ascended to prominence as a female artist of great renown. Her works, which consisted of lifelike statues, were highly sought after by affluent patrons. One of her most notable creations was a statue of the goddess Aphrodite, which was celebrated for its breathtaking beauty and inspired increased devotion to the deity. Phryne's contributions to the art world were significant and enduring, solidifying her legacy as a highly skilled and revered artist.

Aristarete and Eirene

The historical records briefly mention Aristarete, who was the daughter and student of Nearchus, a renowned painter. Although she was not well-known for her artwork, Pliny the Elder mentioned one of her paintings which depicted Asciepius, the Greek god of medicine. As Aristarete's father was active between 570-555 BCE, she was born in the 6th century BCE. Similarly, Eirene was the daughter and student of the painter Kratinos. Pliny the Elder's word choice created confusion, as her female figure painting was either of a girl or the deity Kore. Eirene was also credited with paintings of an older man and a dancer.

Iaia of Cyzicus

Iaia of Cyzicus was not the daughter of an artist and lived and painted in different cities. She is known to be living during (116 -27 BCE). She used a brush and a stylus (a graver at the time). Iaia used tempera (pigment mixed with water and binder) and encaustic (paint mixed with hot wax and oil). "Iaia may have used a special technique of encaustic painting, employing chemical reactions to mix fugitive oils with wax to brush the paint onto the surface of her works." [2] This method prolonged the life of her work than those with a water base. Generally, her subjects were women, including a self-portrait she painted of herself using a mirror. Her work garnered high prices and was often considered better quality than more well-known painters. Iaia never married and lived in Rome, where the art market was strong. Unfortunately, none of the works of this set of painters exist, and we only have the documentation of Pliny the Elder, who lived at a different time. However, information about their personal life exists in historical files, and most historians accept the concept that women were artists.

Helena of Egypt

Helena of Egypt (probably 4th century BCE) was the daughter of Timonos of Egypt. She was believed to be the painter of the Battle of Issos (333 BCE), a significant war between Darius III from Persia and Alexander the Great. Her work is only known from Ptolemy's anecdotal list written in the 1st century CE in his New History and later reinterpreted by Photios I in his Bibliotheka circa 9th century CE. Photios I wrote, "She painted the Battle of Issus when she was at the height of her powers. The picture was displayed in the Temple of Peace under Vespasian." [3]

[1] Plinius Secundus, C, Natural History, Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1968. The Elder Pliny's Chapters on the History of Art (Translated by K. Jex-Blake with commentary by E. Sellers) Chicago, 1968. Retrieved from https://womeninantiquity.wordpress.c...s%20to%20Pliny

[2] Frasca-Rath, A. (2020). The origin (and decline) of painting: Iaia, butades and the concept of 'women's art' in the 19th century. Journal of Art Historiography, (23), 1-17. Retrieved from https://womeninantiquity.wordpress.c...s%20to%20Pliny

[3] Retrieved from http://www.my-favourite-planet.de/en...liotheka-texts