19.3: Renaissance Sculpture

- Page ID

- 53059

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Renaissance Sculpture in Florence

Renaissance sculpture originated in Florence in the 15th century and was deeply influenced by classical sculpture.

Identify the impetus behind the sculptural output in 15th century Florence, its major exponents, and its best known works

Key Points

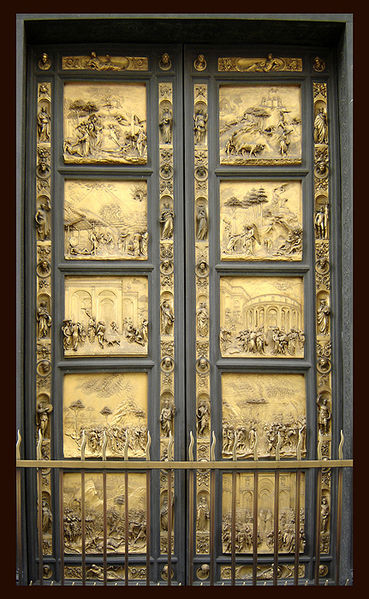

- Renaissance sculpture proper is often thought to have begun with the famous competition for the doors of the Florence baptistry in 1403, which was won by Lorenzo Ghiberti.

- Ghiberti designed a set of doors for the competition, housed in the northern entrance, and another more splendid pair for the eastern entrance, named the Gates of Paradise. Both of these gates depict biblical scenes.

- Ghiberti set up a large workshop in which many famous Florentine sculptors and artists were trained. He revived the lost wax casting of bronze , a technique that had been used by the ancients and had subsequently been lost.

- Donatello created his bronze David for Cosimo de’ Medici. Conceived independently of any architectural surroundings, it was the first known free-standing nude statue produced since antiquity .

- The period was marked by a great increase in patronage of sculpture by the state for public art and by wealthy patrons for their homes. Public sculpture became a crucial element in the appearance of historic city centers. Additionally, portrait sculpture, particularly busts, became hugely popular in Florence.

Key Terms

- allegory: The representation of abstract principles by characters or figures.

- lost wax: A method of casting a sculpture in which a model of the sculpture is made from wax: the model is used to make a mould; when the mould has set, the wax is made to melt and is poured away, leaving the mould ready to be used to cast the sculpture.

- baptistry: A designated space that may stand within a church as a separate room or even as a separate building associated with a church, where a baptismal font is located, and consequently, where the sacrament of Christian baptism (via aspersion or affusion) is performed. Typically during the Renaissance, baptisteries were separate buildings as people would be baptized before entering a church or Cathedral.

Commonly known as “the cradle of the Renaissance,” 15th century Florence was among the largest and richest cities in Europe and its wealthiest residents were enthusiastic patrons of the arts, including sculpture. Departing from the International Gothic style that had previously dominated in Italy, and drawing from the styles of classical antiquity, Renaissance sculpture originated in Florence and was self-consciously influenced by ancient sculpture.

Lorenzo Ghiberti

Renaissance sculpture proper is often thought to begin with the famous competition for the doors of the Florence baptistery in 1403, from which the trial models submitted by the winner, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and the runner up, Filippo Brunelleschi, still survive. Ghiberti’s bronze doors consist of 28 panels depicting scenes from the life of Christ, the four evangelists, and the Church Fathers Saints Ambrose, Jeromy, Gregory, and Augustine. They took 21 years to complete and still stand at the northern entrance of the baptistery, although they are eclipsed by the splendor of his second pair of gates for the eastern entrance, which Michelangelo dubbed “the gates of paradise.” These new doors were commissioned in 1425 and built over a 27-year period. They consist of 10 rectangular panels depicting scenes from the Old Testament and employ a clever use of the recently discovered principles of perspective to add depth to the composition . They are surrounded by a richly decorated gilt framework of fruit and foliage, statuettes of prophets, and busts of the sculptor and his father.

In order to carry out these huge commissions, Ghiberti set up a large workshop in which many famous Florentine sculptors and artists trained in later years, including Donatello, Michelozzo, and Paolo Uccello. He revived the lost wax casting of bronze, a technique which had been used by the ancients and subsequently lost. This made his workshop particularly famous and was a great draw for aspiring artists.

Donatello

Another deeply influential sculptor from Florence was Donatello (1386—1466), who is best known for his work in bas- relief , a form of shallow relief that he used as a medium for the incorporation of significant 15th century sculptural developments in perspectival illusion. Donatello received his early artistic training in a goldsmith’s workshop and then trained briefly in Ghiberti’s studio before undertaking a trip to Rome with Filippo Brunelleschi, where he undertook the study and excavation of Roman architecture and sculpture. Roman art became the single most important influence on Donatello’s work. His foremost sponsor in Florence was Cosimo de’Medici, the city’s greatest patron of art.

Donatello created his bronze David for Cosimo’s court in the Palazzo Medici. Conceived entirely in the round and independent of any architectural surroundings, it was the first known free-standing nude statue produced since antiquity and represented an allegory of civic virtues overcoming brutality and ignorance. This sculpture represented a particularly important development in Renaissance sculpture: the production of sculpture independent of architecture, unlike the preceding International Gothic style where sculpture rarely existed independent of architecture.

Donatello’s other important projects in and near Florence include the marble pulpit of the facade of the Prato cathedral , the carved Cantoria or choir at the Florence Duomo, which was influenced by ancient sarcophagi and Byzantine ivory chests, the Annunciation scene for the Cavalcanti altar in the church of Santa Croce, and a bust of Young Man with a Cameo, the first example of a lay bust portrait since the classical era.

Patronage of Sculpture

The period was marked by a great increase in patronage of sculpture by the state for public art and by wealthy patrons for their homes. Public sculpture became a crucial element in the appearance of historic city centers, and portrait sculpture, particularly busts, became hugely popular in Florence following Donatello’s innovations. These 15th century innovations soon spread throughout Italy and later through the rest of Europe.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Florence - David by Donatello. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Florence_-_David_by_Donatello.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Florenca146. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Florenca146.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- lost wax. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/lost_wax. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Donatello. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Donatello. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Lorenzo Ghiberti. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorenzo_Ghiberti. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sculpture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Sculpture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Scultura rinascimentale. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: it.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Scultura_rinascimentale. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- baptistry. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/baptistry. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- allegory. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/allegory. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike