19.5: The High Renaissance

- Page ID

- 53061

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The High Renaissance

The High Renaissance refers to a short period of exceptional artistic production in the Italian states.

Describe the different periods and characteristic styles of 16th century Italian art

Key Points

- Many art historians consider the High Renaissance to be largely dominated by three individuals: Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci.

- Mannerism , which emerged in the latter years of the Italian High Renaissance, is notable for its intellectual sophistication and its artificial (as opposed to naturalistic) qualities, such as elongated proportions, stylized poses, and lack of clear perspective .

- Some historians regard Mannerism as a degeneration of High Renaissance classicism, or even as an interlude between High Renaissance and Baroque —in which case the dates are usually from c. 1520 to 1600 and it is considered a positive style complete in and of itself.

Key Terms

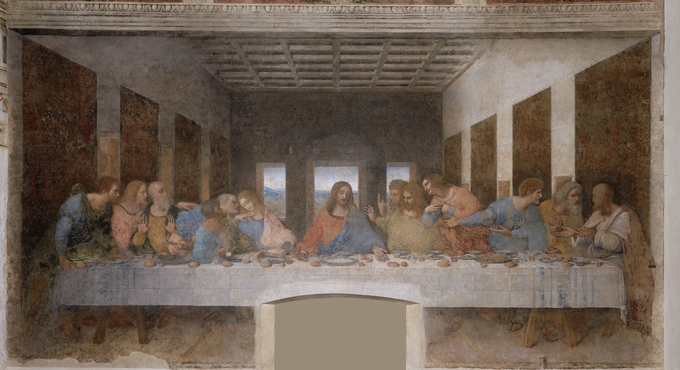

- High Renaissance: The period in art history denoting the apogee of the visual arts in the Italian Renaissance. The High Renaissance period is traditionally taken to have begun in the 1490s, with Leonardo’s fresco of The Last Supper in Milan and the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence, and to have ended in 1527, with the Sack of Rome by the troops of Charles V.

- Mannerism: A style of art developed at the end of the High Renaissance, characterized by the deliberate distortion and exaggeration of perspective, especially the elongation of figures.

High Renaissance Art

High Renaissance art was the dominant style in Italy during the 16th century. Mannerism also developed during this period. The High Renaissance period is traditionally taken to begin in the 1490s, with Leonardo’s fresco of TheLast Supper in Milan, and to end in 1527, with the Sack of Rome by the troops of Charles V. This term was first used in German (“Hochrenaissance”) in the early 19th century. Over the last 20 years, use of the term has been frequently criticized by academic art historians for oversimplifying artistic developments, ignoring historical context, and focusing only on a few iconic works.

High Renaissance art is deemed as “High” because it is seen as the period in which the artistic aims and goals of the Renaissance reached their greatest application. High Renaissance art is characterized by references to classical art and delicate application of developments from the Early Renaissance (such as on-point perspective). Overall, works from the High Renaissance display restrained beauty where all of the parts are subordinate to the cohesive composition of the whole.

Many consider 16th century High Renaissance art to be largely dominated by three individuals: Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci. Michelangelo excelled as a painter, architect, and sculptor and demonstrated a mastery of portraying the human figure. His frescoes rank among the greatest works of Renaissance art. Raphael was skilled in creating perspective and in the delicate use of color. Leonardo da Vinci painted two of the most well known works of Renaissance art: The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa. Leonardo da Vinci was a generation older than Michelangelo and Raphael, yet his work is stylistically consistent with the High Renaissance.

The Last Supper, 1495–1498, Leonardo da Vinci

Mannerism

Mannerism is an artistic style that emerged from the later years of the 16th century and lasted as a popular aesthetic style in Italy until about 1580, when the Baroque began to replace it (although Northern Mannerism continued into the early 17th century throughout much of Europe). Michelangelo’s later works, such as The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel , and the Laurentian Library, are considered to be Mannerist style by some art historians.

Last Judgment, 1536-1541, Michelangelo

Some historians regard Mannerism as a degeneration of High Renaissance classicism, or even as an interlude between High Renaissance and Baroque—in which case the dates are usually from c. 1520 to 1600 and it is considered a positive style complete in and of itself. The definition of Mannerism, and the phases within it, continues to be the subject of debate among art historians. For example, some scholars have applied the label to certain early modern forms of literature (especially poetry) and music of the 16th and 17th centuries. The term is also used to refer to some Late Gothic painters working in northern Europe from about 1500 to 1530, especially the Antwerp Mannerists, a group unrelated to the Italian movement. Mannerist art is characterized by elongated forms, contorted poses, and irrational settings.

Painting in the High Renaissance

The term “High Renaissance” denotes a period of artistic production that is viewed by art historians as the height, or the culmination, of the Renaissance period.

Describe the key factors that contributed to the development of High Renaissance painting and the period’s stylistic features

Key Points

- The High Renaissance was centered in Rome , and lasted from about 1490 to 1527, the end of the period marked by the Sack of Rome .

- The restrained beauty of a High Renaissance painting is created when all of the parts and details of the work support the cohesive whole.

- The prime example of High Renaissance painting is The School of Athens by Raphael.

Key Terms

- High Renaissance: A period of artistic production that is viewed by art historians as the height, or the culmination, of the Renaissance period. The period is dated from 1490–1527.

The High Renaissance

The term “High Renaissance” denotes a period of artistic production that is viewed by art historians as the height, or the culmination, of the Renaissance period. Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael are considered High Renaissance painters. While the term has become controversial, with some scholars arguing that it oversimplifies artistic developments and historical context, it is hard to ignore the works of these High Renaissance artists as they remain so iconic even into the 21st century.

High Renaissance Style

The High Renaissance was centered in Rome, and lasted from about 1490 to 1527, with the end of the period marked by the Sack of Rome. Stylistically, painters during this period were influenced by classical art, and their works were harmonious. The restrained beauty of a High Renaissance painting is created when all of the parts and details of the work support the cohesive whole. While earlier Renaissance artists would stress the perspective of a work, or the technical aspects of a painting, High Renaissance artists were willing to sacrifice technical principles in order to create a more beautiful, harmonious whole. The factors that contributed to the development of High Renaissance painting were twofold. Traditionally, Italian artists had painted in tempera paint. During the High Renaissance, artists began to use oil paints, which are easier to manipulate and allow the artist to create softer forms . Additionally, the number and diversity of patrons increased, which allowed for greater development in art.

If Rome was the center for the High Renaissance, its greatest patron was Pope Julius II. As patron of the arts, Pope Julius II supported many important artists, including Michelangelo and Raphael. The prime example of High Renaissance painting is The School of Athens by Raphael.

Raphael was commissioned by Pope Julius II to redecorate the Pope’s living space in Rome. As part of this project, Raphael was asked to paint in the Pope’s library, or the Stanza della Segnatura. The School of Athens is one of the frescoes within this room. The fresco represents the subject of philosophy and is consistently pointed to as the epitome of High Renaissance painting. The work demonstrates many key points of the High Renaissance style; references to classical antiquity are paramount as Plato and Aristotle are the central figures of this work. There is a clear vanishing point , demonstrating Raphael’s command of technical aspects that were so important in Renaissance painting. But above all, the numerous figures in the work show restrained beauty and serve to support the harmonious, cohesive work. While the figures are diverse and dynamic, nothing serves to detract from the painting as a whole.

Sculpture in the High Renaissance

Sculpture in the High Renaissance demonstrates the influence of classical antiquity and ideal naturalism.

Describe the characteristics of High Renaissance sculpture

Key Points

- Sculptors during the High Renaissance were deliberately quoting classical precedents and they aimed for ideal naturalism in their works.

- Michelangelo (1475–1564) is the prime example of a sculptor during the Renaissance; his works best demonstrate the goals and ideals of the High Renaissance sculptor.

During the Renaissance, an artist was not just a painter, or an architect, or a sculptor. They were typically all three. As a result, we see the same prominent names producing sculpture and the great Renaissance paintings. Additionally, the themes and goals of High Renaissance sculpture are very much the same as High Renaissance painting. Sculptors during the High Renaissance were deliberately quoting classical precedents and they aimed for ideal naturalism in their works. Michelangelo (1475–1564) is the prime example of a sculptor during the Renaissance; his works best demonstrate the goals and ideals of the High Renaissance sculptor.

Bacchus

The Bacchus is Michelangelo’s first recorded commission in Rome . The work is made of marble, it is life sized, and it is carved in the round . The sculpture is of the god of wine, who is holding a cup and appears drunk. The references to classical antiquity are clear in the subject matter, and the body of the god is based on the Apollo Belvedere, which Michelangelo would have seen while in Rome. Not only is the subject matter influenced by antiquity, but so are the artistic influences.

Pieta

While the Pieta is not based on classical antiquity in subject matter, the forms display the restrained beauty and ideal naturalism that was influenced by classical sculpture. Commissioned by a French Cardinal for his tomb in Old St. Peter’s, it is the work that made Michelangelo’s reputation. The subject matter of the Virgin cradling Christ after the crucifixion was uncommon in the Italian Renaissance, indicating that it was chosen by the patron .

David

When the David was completed, it was intended to be a buttress on the back of the Florentine Cathedral . But Florentines during that time recognized it as so special and beautiful that they actually had a meeting about where to place the sculpture. Members of the group that met included the artists Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli. What about this work made it stand out so spectacularly to Michelangelo’s peers? The work demonstrates classical influence. The work is nude, in emulation of Greek and Roman sculptures, and the David stands in a contrapposto pose. He shows restrained beauty and ideal naturalism. Additionally, the work demonstrates an interest in psychology, which was new to the High Renaissance, as Michelangelo depicts David concentrating in the moments before he takes down the giant. The subject matter was also very special to Florence as David was traditionally a civic symbol. The work was ultimately placed in the Palazzo Vecchio and remains the prime example of High Renaissance sculpture.

Architecture in the High Renaissance

Architecture during the High Renaissance represents a culmination of the architectural developments that were made during the Renaissance.

Describe the important architects of the High Renaissance and their achievements

Key Points

- The Renaissance is divided into the Early Renaissance (c. 1400–1490) and the High Renaissance (c. 1490–1527).

- During the Early Renaissance, theories on art were developed, new advancements in painting and architecture were made, and the style was defined. The High Renaissance denotes a period that is seen as the culmination of the Renaissance period.

- Renaissance architecture is characterized by symmetry and proportion, and is directly influenced by the study of antiquity .

- The architects most representative of the High Renaissance are Donato Bramante (1444–1514) and Andrea Palladio (1508–1580).

The Renaissance is divided into the Early Renaissance (c. 1400–1490) and the High Renaissance (c. 1490–1527). During the Early Renaissance, theories on art were developed, new advancements in painting and architecture were made, and the style was defined. The High Renaissance denotes a period that is seen as the culmination of the Renaissance period, when artists and architects implemented these ideas and artistic principles in harmonious and beautiful ways.

Renaissance architecture is characterized by symmetry and proportion, and is directly influenced by the study of antiquity. While Renaissance architecture was defined in the Early Renaissance by figures such as Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) and Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), the architects most representative of the High Renaissance are Donato Bramante (1444–1514) and Andrea Palladio (1508–1580).

Donato Bramante

A key figure in Roman architecture during the High Renaissance was Donato Bramante (1444–1514). Bramante was born in Urbino and first came to prominence as an architect in Milan before traveling to Rome . In Rome, Bramante was commissioned by Ferdinand and Isabella to design the Tempietto, a temple that marks what was believed to be the exact spot where Saint Peter was martyred. The temple is circular, similar to early Christian martyriums, and much of the design is inspired by the remains of the ancient Temple Vesta.

The Tempietto is considered by many scholars to be the premier example of High Renaissance architecture. With its perfect proportions, harmony of its parts, and direct references to ancient architecture, the Tempietto embodies the Renaissance. This structure has been described as Bramante’s “calling card” to Pope Julius II, the important Renaissance patron of the arts who would then employ Bramante in the historic design of the new St. Peter’s Basilica .

Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) was the Chief Architect in the Republic of Venice in the 16th century. Deeply inspired by Roman and Greek architecture, Palladio is widely considered one of the most influential individuals in the history of Western architecture. All of his buildings are located in what was the Venetian Republic, but his teachings, summarized in the architectural treatise, The Four Books of Architecture, gained him wide recognition beyond Italy. Palladian Architecture , named after him, adhered to classical Roman principles that Palladio rediscovered, applied, and explained in his works. Palladio designed many palaces, villas, and churches, but his reputation has been founded on his skill as a designer of villas. Palladian villas are located mainly in the province of Vicenza.

Villas

Palladio established an influential new building format for the agricultural villas of the Venetian aristocracy. His designs were based on practicality and employed fewer reliefs . He consolidated the various standalone farm outbuildings into a single impressive structure and arranged as a highly organized whole, dominated by a strong center and symmetrical side wings, as illustrated at Villa Barbaro. The Palladian villa configuration often consists of a centralized block raised on an elevated podium, accessed by grand steps and flanked by lower service wings. This format, with the quarters of the owner at the elevated center of his own world, found resonance as a prototype for Italian villas and later for the country estates of the British nobility. Palladio developed his own more flexible prototype for the plan of the villas to moderate scale and function.

Leonardo da Vinci

While Leonardo da Vinci is admired as a scientist, an academic, and an inventor, he is most famous for his achievements as the painter of several Renaissance masterpieces.

Describe the works of Leonardo da Vinci that demonstrate his most innovative techniques as an artist

Key Points

- Among the qualities that make da Vinci’s work unique are the innovative techniques that he used in laying on the paint, his detailed knowledge of anatomy, his innovative use of the human form in figurative composition , and his use of sfumato .

- Among the most famous works created by da Vinci is the small portrait titled the Mona Lisa, known for the elusive smile on the woman’s face, brought about by the fact that da Vinci subtly shadowed the corners of the mouth and eyes so that the exact nature of the smile cannot be determined.

- Despite his famous paintings, da Vinci was not a prolific painter; he was a prolific draftsman, keeping journals full of small sketches and detailed drawings recording all manner of things that interested him.

Key Terms

- sfumato: In painting, the application of subtle layers of translucent paint so that there is no visible transition between colors, tones, and often objects.

While Leonardo da Vinci is greatly admired as a scientist, an academic, and an inventor, he is most famous for his achievements as the painter of several Renaissance masterpieces. His paintings were groundbreaking for a variety of reasons and his works have been imitated by students and discussed at great length by connoisseurs and critics.

Among the qualities that make da Vinci’s work unique are the innovative techniques that he used in laying on the paint, his detailed knowledge of anatomy, his use of the human form in figurative composition, and his use of sfumato. All of these qualities are present in his most celebrated works, the Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, and the Virgin of the Rocks.

The Last Supper

Da Vinci’s most celebrated painting of the 1490s is The Last Supper, which was painted for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan. The painting depicts the last meal shared by Jesus and the 12 Apostles where he announces that one of the them will betray him. When finished, the painting was acclaimed as a masterpiece of design. This work demonstrates something that da Vinci did very well: taking a very traditional subject matter, such as the Last Supper, and completely re-inventing it.

Prior to this moment in art history, every representation of the Last Supper followed the same visual tradition: Jesus and the Apostles seated at a table. Judas is placed on the opposite side of the table of everyone else and is effortlessly identified by the viewer . When da Vinci painted The Last Supper he placed Judas on the same side of the table as Christ and the Apostles, who are shown reacting to Jesus as he announces that one of them will betray him. They are depicted as alarmed, upset, and trying to determine who will commit the act. The viewer also has to determine which figure is Judas, who will betray Christ. By depicting the scene in this manner, da Vinci has infused psychology into the work.

Unfortunately, this masterpiece of the Renaissance began to deteriorate immediately after da Vinci finished painting, due largely to the painting technique that he had chosen. Instead of using the technique of fresco , da Vinci had used tempera over a ground that was mainly gesso in an attempt to bring the subtle effects of oil paint to fresco. His new technique was not successful, and resulted in a surface that was subject to mold and flaking.

Mona Lisa

Among the works created by da Vinci in the 16th century is the small portrait known as the Mona Lisa, or La Gioconda, “the laughing one.” In the present era it is arguably the most famous painting in the world. Its fame rests, in particular, on the elusive smile on the woman’s face—its mysterious quality brought about perhaps by the fact that the artist has subtly shadowed the corners of the mouth and eyes so that the exact nature of the smile cannot be determined.

The shadowy quality for which the work is renowned came to be called sfumato, the application of subtle layers of translucent paint so that there is no visible transition between colors, tones , and often objects. Other characteristics found in this work are the unadorned dress, in which the eyes and hands have no competition from other details; the dramatic landscape background, in which the world seems to be in a state of flux; the subdued coloring; and the extremely smooth nature of the painterly technique, employing oils, but applied much like tempera and blended on the surface so that the brushstrokes are indistinguishable. And again, da Vinci is innovating upon a type of painting here. Portraits were very common in the Renaissance. However, portraits of women were always in profile, which was seen as proper and modest. Here, da Vinci present a portrait of a woman who not only faces the viewer but follows them with her eyes.

Virgin and Child with St. Anne

In the painting Virgin and Child with St. Anne, da Vinci’s composition again picks up the theme of figures in a landscape. What makes this painting unusual is that there are two obliquely set figures superimposed. Mary is seated on the knee of her mother, St. Anne. She leans forward to restrain the Christ Child as he plays roughly with a lamb, the sign of his own impending sacrifice . This painting influenced many contemporaries, including Michelangelo, Raphael, and Andrea del Sarto. The trends in its composition were adopted in particular by the Venetian painters Tintoretto and Veronese.

Raphael

Raphael was an Italian Renaissance painter and architect whose work is admired for its clarity of form and ease of composition.

Discuss Raphael influences and artistic achievements

Key Points

- Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael forms the traditional trinity of great masters of the High Renaissance . He was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop, and despite his death at 30, he had a large body of work.

- Some of Raphael’s most striking artistic influences come from the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci; because of this inspiration, Raphael gave his figures more dynamic and complex positions in his earlier compositions .

- Raphael’s “Stanze” masterpieces are very large and complex compositions that have been regarded among the supreme works of the High Renaissance. They give a highly idealized depiction of the forms represented, and the compositions, though very carefully conceived in drawings, achieve sprezzatura , the art of performing a task so gracefully it looks effortless.

Key Terms

- sprezzatura:The art of performing a difficult task so gracefully that it looks effortless.

- loggia:A roofed, open gallery.

- contrapposto:The position of a figure whose hips and legs are twisted away from the direction of the head and shoulders.

Overview

Raphael (1483–1520) was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form and ease of composition and for its visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur. Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael forms the traditional trinity of great masters of that period. He was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop; despite his death at 30, a large body of his work remains among the most famous of High Renaissance art.

Influences

Some of Raphael’s most striking artistic influences come from the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci. In response to da Vinci’s work, in some of Raphael’s earlier compositions he gave his figures more dynamic and complex positions. For example, Raphael’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1507) borrows from the contrapposto pose of da Vinci’s Leda and the Swans.

While Raphael was also aware of Michelangelo’s works, he deviates from his style . In his Deposition of Christ, Raphael draws on classical sarcophagi to spread the figures across the front of the picture space in a complex and not wholly successful arrangement.

The Stanze Rooms and the Loggia

In 1511, Raphael began work on the famous Stanze paintings, which made a stunning impact on Roman art, and are generally regarded as his greatest masterpieces. The Stanza della Segnatura contains The School of Athens, Poetry, Disputa, and Law. The School of Athens, depicting Plato and Aristotle, is one of his best known works. These very large and complex compositions have been regarded ever since as among the supreme works of the High Renaissance, and the “classic art” of the post-antique West. They give a highly idealized depiction of the forms represented, and the compositions—though very carefully conceived in drawings—achieve sprezzatura, a term invented by Raphael’s friend Castiglione, who defined it as “a certain nonchalance that conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless.”

View of the Stanze della Segnatura, frescoes painted by Raphael

In the later phase of Raphael’s career, he designed and painted the Loggia at the Vatican, a long thin gallery that was open to a courtyard on one side and decorated with Roman style grottesche. He also produced a number of significant altarpieces , including The Ecstasy of St. Cecilia and the Sistine Madonna. His last work, on which he was working until his death, was a large Transfiguration which, together with Il Spasimo, shows the direction his art was taking in his final years, becoming more proto-Baroque than Mannerist .

The Master’s studio

Raphael ran a workshop of over 50 pupils and assistants, many of whom later became significant artists in their own right. This was arguably the largest workshop team assembled under any single old master painter, and much higher than the norm. They included established masters from other parts of Italy, probably working with their own teams as sub-contractors, as well as pupils and journeymen.

Architecture

In architecture, Raphael’s skills were employed by the papacy and wealthy Roman nobles. For instance, Raphael designed the plans for the the Villa Madama, which was to be a lavish hillside retreat for Pope Clement VII (and was never finished). Even incomplete, Raphael’s schematic was the most sophisticated villa design yet seen in Italy, and greatly influenced the later development of the genre . It also appears to be the only modern building in Rome of which Palladio made a measured drawing.

Draftsman

Raphael was one of the finest draftsmen in the history of Western art, and used drawings extensively to plan his compositions. According to a near-contemporary, when beginning to plan a composition, he would lay out a large number of his stock drawings on the floor, and begin to draw “rapidly,” borrowing figures from here and there. Over 40 sketches survive for the Disputa in the Stanze, and there may well have been many more originally (over 400 sheets survived altogether).

As evidenced in his sketches for the Madonna and Child, Raphael used different drawings to refine his poses and compositions, apparently to a greater extent than most other painters. Most of Raphael’s drawings are rather precise—even initial sketches with naked outline figures are carefully drawn, and later drawings often have a high degree of finish, with shading and sometimes highlights in white. They lack the freedom and energy of some of da Vinci’s and Michelangelo’s sketches, but are almost always very satisfying aesthetically.

Michelangelo

Michelangelo was a 16th century Florentine artist renowned for his masterpieces in sculpture, painting, and architectural design.

Discuss Michelangelo’s achievements in sculpture, painting, and architecture

Key Points

- Michelangelo created his colossal marble statue, the David, out of a single block of marble, which established his prominence as a sculptor of extraordinary technical skill and strength of symbolic imagination.

- In painting, Michelangelo is renowned for the ceiling and The Last Judgement of the Sistine Chapel , where he depicted a complex scheme representing Creation, the Downfall of Man, the Salvation of Man, and the Genealogy of Christ.

- Michelangelo’s chief contribution to Saint Peter’s Basilica was the use of a Greek Cross form and an external masonry of massive proportions, with every corner filled in by a stairwell or small vestry. The effect is a continuous wall-surface that appears fractured or folded at different angles.

Key Terms

- contrapposto: The standing position of a human figure where most of the weight is placed on one foot, and the other leg is relaxed. The effect of contrapposto in art makes figures look very naturalistic.

- Sistine Chapel: The best-known chapel in the Apostolic Palace.

Michelangelo was a 16th century Florentine artist renowned for his masterpieces in sculpture, painting, and architectural design. His most well known works are the David, the Last Judgment, and the Basilica of Saint Peter’s in the Vatican.

Sculpture: David

In 1504, Michelangelo was commissioned to create a colossal marble statue portraying David as a symbol of Florentine freedom. The subsequent masterpiece, David, established the artist’s prominence as a sculptor of extraordinary technical skill and strength of symbolic imagination. David was created out of a single marble block, and stands larger than life, as it was originally intended to adorn the Florence Cathedral . The work differs from previous representations in that the Biblical hero is not depicted with the head of the slain Goliath, as he is in Donatello’s and Verrocchio’s statues; both had represented the hero standing victorious over the head of Goliath. No earlier Florentine artist had omitted the giant altogether. Instead of appearing victorious over a foe, David’s face looks tense and ready for combat. The tendons in his neck stand out tautly, his brow is furrowed, and his eyes seem to focus intently on something in the distance. Veins bulge out of his lowered right hand, but his body is in a relaxed contrapposto pose, and he carries his sling casually thrown over his left shoulder. In the Renaissance , contrapposto poses were thought of as a distinctive feature of antique sculpture.

The sculpture was intended to be placed on the exterior of the Duomo, and has become one of the most recognized works of Renaissance sculpture.

Painting: The Last Judgement

In painting, Michelangelo is renowned for his work in the Sistine Chapel. He was originally commissioned to paint tromp-l’oeil coffers after the original ceiling developed a crack. Michelangelo lobbied for a different and more complex scheme, representing Creation, the Downfall of Man, the Promise of Salvation through the prophets, and the Genealogy of Christ. The work is part of a larger scheme of decoration within the chapel that represents much of the doctrine of the Catholic Church.

The composition eventually contained over 300 figures, and had at its center nine episodes from the Book of Genesis, divided into three groups: God’s Creation of the Earth, God’s Creation of Humankind, and their fall from God’s grace, and lastly, the state of Humanity as represented by Noah and his family. Twelve men and women who prophesied the coming of the Jesus are painted on the pendentives supporting the ceiling. Among the most famous paintings on the ceiling are The Creation of Adam, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the Great Flood, the Prophet Isaiah and the Cumaean Sibyl. The ancestors of Christ are painted around the windows.

The fresco of The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel was commissioned by Pope Clement VII, and Michelangelo labored on the project from 1536–1541. The work is located on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, which is not a traditional placement for the subject. Typically, last judgement scenes were placed on the exit wall of churches as a way to remind the viewer of eternal punishments as they left worship. The Last Judgment is a depiction of the second coming of Christ and the apocalypse; where the souls of humanity rise and are assigned to their various fates, as judged by Christ, surrounded by the Saints. In contrast to the earlier figures Michelangelo painted on the ceiling, the figures in The Last Judgement are heavily muscled and are in much more artificial poses, demonstrating how this work is in the Mannerist style .

In this work Michelangelo has rejected the orderly depiction of the last judgement as established by Medieval tradition in favor of a swirling scene of chaos as each soul is judged. When the painting was revealed it was heavily criticized for its inclusion of classical imagery as well as for the amount of nude figures in somewhat suggestive poses. The ill reception that the work received may be tied to the Counter Reformation and the Council of Trent , which lead to a preference for more conservative religious art devoid of classical references. Although a number of figures were made more modest with the addition of drapery, the changes were not made until after the death of Michelangelo, demonstrating the respect and admiration that was afforded to him during his lifetime.

Architecture: St. Peter’s Basilica

Finally, although other architects were involved, Michelangelo is given credit for designing St. Peter’s Basilica. Michelangelo’s chief contribution was the use of a symmetrical plan of a Greek Cross form and an external masonry of massive proportions, with every corner filled in by a stairwell or small vestry. The effect is of a continuous wall surface that is folded or fractured at different angles, lacking the right angles that usually define change of direction at the corners of a building. This exterior is surrounded by a giant order of Corinthian pilasters all set at slightly different angles to each other, in keeping with the ever-changing angles of the wall’s surface. Above them the huge cornice ripples in a continuous band, giving the appearance of keeping the whole building in a state of compression .

The Venetian Painters of the High Renaissance

Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese were the preeminent Venetian painters of the High Renaissance.

Summarize the impact of the paintings of Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese on art of the Venetian High Renaissance

Key Points

- The Venetian High Renaissance artists Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese employed novel techniques of color, scale, and composition , which established them as acclaimed artists north of Rome .

- In particular, these three painters followed the Venetian School ‘s preference of color over disegno .

- Giorgio Barbarelli da Castlefranco, known as Giorgione (c. 1477–1510), is an artist who had considerable impact on the Venetian High Renaissance. Giorgione was the first to paint with oil on canvas.

- Tiziano Vecelli, or Titian (1490–1576), was arguably the most important member of the Venetian school, as well as one of the most versatile. His use of color would have a profound influence not only on painters of the Italian Renaissance, but on future generations in Western art.

- Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) was one of the primary Renaissance painters in Venice , known for his paintings such as The Wedding at Cana and The Feast in the House of Levi.

Key Terms

- disegno: Drawing or design.

- Venetian School: The distinctive, thriving, and influential art scene in Venice, Italy, starting from the late 15th century.

Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese were the preeminent painters of the Venetian High Renaissance. All three similarly employed novel techniques of color and composition, which established them as acclaimed artists north of Rome. In particular, Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese follows the Venetian School’s preference of color over disegno.

Giorgione

Giorgio Barbarelli da Castlefranco, known as Giorgione (c. 1477–1510), is an artist who had considerable impact on the Venetian High Renaissance. Unfortunately, art historians do not know much about Giorgione, partly because of his early death at around age 30, and partly because artists in Venice were not as individualistic as artists in Florence. While only six paintings are accredited to him, they demonstrate his importance in the history of art as well as his innovations in painting.

Giorgione was the first to paint with oil on canvas. Previously, people who used oils were painting on panel, not canvas. His works do not contain much under-drawing, demonstrating how he did not adhere to Florentine disegno, and his subject matters remain elusive and mysterious. One of his works that demonstrates all three of these elements is The Tempest (c. 1505–1510). This work is oil on canvas, x-rays show there is very little under drawing, and the subject matter remains one of the most debated issues in art history.

Titian

Tiziano Vecelli, or Titian (1490–1576), was arguably the most important member of the 16th century Venetian school, as well as one of the most versatile; he was equally adept with portraits, landscape backgrounds, and mythological and religious subjects. His painting methods, particularly in the application and use of color, would have a profound influence not only on painters of the Italian Renaissance, but on future generations of Western art. Over the course of his long life Titian’s artistic manner changed drastically, but he retained a lifelong interest in color. Although his mature works may not contain the vivid, luminous tints of his early pieces, their loose brushwork and subtlety of polychromatic modulations were without precedent

In 1516, Titian completed his well-known masterpiece, the Assumption of the Virgin, or the Assunta, for the high altar of the church of the Frari. This extraordinary piece of colorism, executed on a grand scale rarely before seen in Italy, created a sensation. The pictorial structure of the Assumption—uniting in the same composition two or three scenes superimposed on different levels, earth and heaven, the temporal and the infinite—was continued in a series of his works, finally reaching a classic formula in the Pesaro Madonna (better known as the Madonna di Ca’ Pesaro). This perhaps is Titian’s most studied work; his patiently developed plan is set forth with supreme display of order and freedom, originality and style . Here, Titian gave a new conception of the traditional groups of donors and holy persons moving in aerial space , the plans and different degrees set in an architectural framework.

Veronese

Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) was one of the primary Renaissance painters in Venice, well known for paintings such as The Wedding at Cana and The Feast in the House of Levi. Veronese is known as a supreme colorist, and for his illusionistic decorations in both fresco and oil. His most famous works are elaborate narrative cycles, executed in the dramatic and colorful style, full of majestic architectural settings and glittering pageantry.

His large paintings of biblical feasts executed for the refectories of monasteries in Venice and Verona are especially notable. For example, in The Wedding at Cana, which was painted in 1562–1563 in collaboration with Palladio, Veronese arranged the architecture to run mostly parallel to the picture plane , accentuating the processional character of the composition. The artist’s decorative genius was to recognize that dramatic perspective effects would have been tiresome in a living room or chapel, and that the narrative of the picture could best be absorbed as a colorful diversion.

The Wedding at Cana offers little in the representation of emotion: rather, it illustrates the carefully composed movement of its subjects along a primarily horizontal axis. Most of all, it is about the incandescence of light and color. Even as Veronese’s use of color attained greater intensity and luminosity, his attention to narrative, human sentiment, and a more subtle and meaningful physical interplay between his figures became evident.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- C39Altima_Cena_-_Da_Vinci_5.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Last_Supper_(Leonardo_da_Vinci). License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Last_Judgement_28Michelangelo29.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Last_Judgment_(Michelangelo). License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Mannerism. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Mannerism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- High Renaissance. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Renaissance. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mannerism. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mannerism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Italian art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_art%23Arts_of_the_late_1400s_and_early_1500s. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- High Renaissance. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/High%20Renaissance. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- School of Athens. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_School_of_Athens. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The School of Athens. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_School_of_Athens. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- High Renaissance. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Renaissance. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Piet_-_Wikipedia_the_free_encyclopedia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Piet%C3%A0. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 27David27_by_Michelangelo_JBU0001.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Michelangelo. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Michelangelo_Bacchus.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Bacchus_(Michelangelo). License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Bacchus (Michelangelo). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Bacchus_(Michelangelo). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- David (Michelangelo). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/David_(Michelangelo). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Michelangelo. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Michelangelo. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Michelangelo. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Michelangelo. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roma-tempiettobramante01R.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Pietro_in_Montorio#The_Tempietto. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Villa_Barbaro_panoramica_fronte_Marcok.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_Barbaro. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Andrea Palladio. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrea_Palladio. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- San Pietro in Montario. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Pietro_in_Montorio#The_Tempietto. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Italian Renaissance. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_Renaissance. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Donato Bramante. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Donato_Bramante. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- High Renaissance. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Renaissance. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Leonardo_Da_Vinci_-_Vergine_delle_Rocce_28Louvre29.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Virgin_of_the_Rocks. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- u00daltima Cena - Da Vinci 5. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:%C3%9Altima_Cena_-_Da_Vinci_5.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Mona Lisa, by Leonardo da Vinci, from C2RMF retouched. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mona_Lisa,_by_Leonardo_da_Vinci,_from_C2RMF_retouched.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Leonardo da vinci, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne 01. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_da_vinci,_The_Virgin_and_Child_with_Saint_Anne_01.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Leonardo da Vinci. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonardo_da_Vinci%23Painting. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- sfumato. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/sfumato. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Leonardo Da Vinci. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonardo%20Da%20Vinci. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Raffael stcatherina. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Raffael_stcatherina.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Raffaello2C_pala_baglioni2C_deposizione.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Deposition_(Raphael). License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 1_Estancia_del_Sello_28Vista_general_I29.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Raphael_Rooms. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Raffaello, studi per madonne col bambino. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Raffaello,_studi_per_madonne_col_bambino.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Saint Catherine of Alexandria (Raphael). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Catherine_of_Alexandria_(Raphael). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Raphael. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Raphael. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- contrapposto. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/contrapposto. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- sprezzatura. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/sprezzatura. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- loggia. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/loggia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- David von Michelangelo. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:David_von_Michelangelo.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Petersdom von Engelsburg gesehen. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Petersdom_von_Engelsburg_gesehen.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Michelangelo, Giudizio Universale 02. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Michelangelo,_Giudizio_Universale_02.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- St Peter's Basilica. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Peter's_Basilica%23Michelangelo.27s_contribution. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- David (Michelangelo). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/David_(Michelangelo)%23Interpretation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Michelangelo. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Michelangelo%23Life_and_works. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- contrapposto. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/contrapposto. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sistine Chapel. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Sistine%20Chapel. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Paolo Veronese, The Wedding at Cana. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Paolo_Veronese,_The_Wedding_at_Cana.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The Tempest, Giorgione, c.1505-1510. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Giorgione. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tizian 041. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tizian_041.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The Wedding at Cana. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wedding_at_Cana. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Assumption of the Virgin (Titian). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Assumption_of_the_Virgin_(Titian). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Tempest (Giorgione). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tempest_(Giorgione). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Giorgione. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Giorgione. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tintoretto. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tintoretto. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Paolo Veronese. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Paolo_Veronese%23Villa_Barbaro_and_refectory_paintings. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Titian. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Titian. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Venetian School. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian%20School. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//art-history/definition/connoisseurship. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike