19.2: The New Arts of Memory

- Page ID

- 232377

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The AIDS quilt's success as a memorial has been due largely to its divergence from conventional models of monumentality. Mobile rather than static, flexible rather than rigid, personal rather than absolute, it suggests a form of active memory based in ritual, participation, and change, rather than a didactic history invested in oversized stone monuments. In this sense, the AIDS quilt has shared in recent redefinitions of the arts of memory.

Monuments and Memorials Redefined

Monuments have changed radically over the past quarter century. In the United States, where a polarized national politics has complicated the meaning of national identity, a new skepticism has arisen about the capacity of triumphal arches, equestrian statues, and grand obelisks to embody public memory. Many theorists now argue that such monuments stifle lived history beneath layers of didactic nationalist myth and prevent the internalization of memory by fixing history in external, material form. One of the inspirations for these critiques was the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL. World War II memorials in the United States, designed for a relatively unified public with a sense of clear moral certitude about the conflict, had tended to adopt traditional modes of heroic figuration. But when a national design competition was announced in 1980 for a Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Americans were still bitterly divided about the purpose and meaning of the war. Because it had lacked a clear motivation or resolution, because American soldiers had been associated with atrocities during the campaign, and because the soldiers that were killed disproportionately represented minority groups and lower income levels, the memory of the war continued to be unsettling for Americans. Acknowledging the complexity of the issue, the criteria for the design competition stipulated only that the memorial encourage contemplation- and explicitly forbade the designs from making overt political statements about the war.

Out of more than 1,400 entries to the open, anonymous competition for the memorial, the panel selected a stark and simple design that turned out to have been created by a twenty-one-year-old architecture student named Maya Lin (b. 1959). In contrast to the towering white monuments populating the rest of the National Mall, Lin's memorial would consist entirely of polished black granite and would be sited below ground level along a shallow embankment. The memorial would not be figurative but would instead take the form of a 500-foot-long, V-shaped wall, tapered at each end. Like a work of Land Art or Minimalism, the wall would establish an environmental situation rather than define a discrete artistic form. The names of each of the soldiers killed during the conflict (some 58,000 of them) would be incised into the stone according to the chronological order of their deaths, without regard for military rank.

Before the memorial was built, its design became the subject of intense public controversy. Members of the public who had expected a traditional design were quick to react against the emasculation suggested by what many took to calling the 'black gash of shame." Some expressed doubts about Lin's qualifications (as a very young woman) to represent the experiences of middle-aged American male war veterans. Some veterans were concerned that the memorial's equivocation about the meaning of the war would permanently enshrine the hostility and disavowal they had faced upon their return to the United States. Class concerns also intruded, since the abstraction of the design was prone to be interpreted as an elite pretension overwriting the populist preference for representational art.

But, as Lin relates, "The minute the piece was opened to the public, the controversy ceased, and I started getting the most amazing letters from veterans." 16 Viewers responded to the memorial's reticence, its intimacy, and the interpretive freedom it granted to them. Unlike the billboard-scale pronouncements carved into the other mall memorials, the thousands of names of the Vietnam dead are inscribed at an intimate scale-they require the viewer to come within a few feet of the wall in order to read them (fig. 19.16). Once at close range, viewers discover their own images reflected among the names in the polished facade. Rubbings of individual names can be taken from the surface of the monument; it invites both tactile and emotional intimacy. The memorial engages each viewer individually, even as its cumulative registration of names acknowledges a broader collective context (in this sense, Lin's design shares in the participatory spatial aesthetic of Minimalism).

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial, by presenting itself as an absence rather than a presence, radically inverted standard monumental strategy. It did not provide a form for memory so much as it provided a space for memory, and its impact on future memorial design in the United States and abroad was immense.

Memory and the Museum

Like monuments, museums and galleries are repositories of cultural memory. And they, too, have been engaged in a redefinition of memorial practice. In projects that synthesize institutional critique (introduced in Chapter 18) and memorial discourse, many contemporary artists have worked to change the shape of American history by intervening in the display and curation of museum collections.

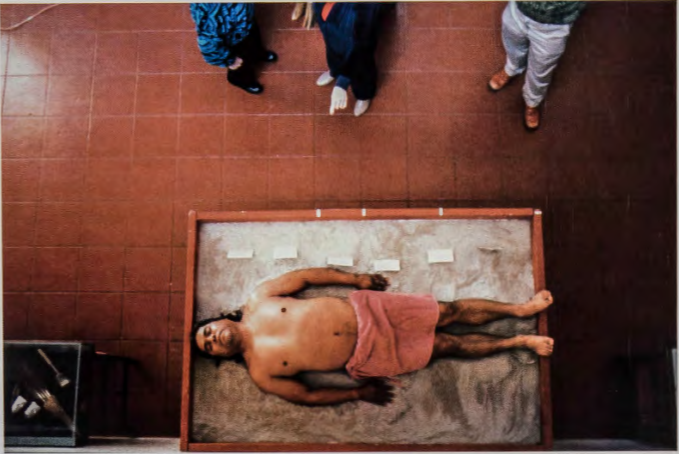

JAMES LUNA. James Luna (b. 1950) lives on the La Jolla Indian Reservation in northern San Diego County, California. He uses performance to challenge longstanding practices of placing Native American art in natural history museums rather than art museums, showing that this practice perpetuates damaging assumptions about Native Americans in both the past and the present. In Artifact Piece of 1987 (fig. 19.17), Luna resuscitated the tradition of live ethnographic display (see Box, "The Indian as Spectacle," in Chapter 7, p. 221) by lying in a glass case, wearing only a loincloth, in San Diego's Museum of Man. Typed labels on the display case described Luna's body-including its most intense physical and emotional scars-in the language of detached anthropological description: "Having been married less than two years, the sharing of emotional scars from alcoholic family backgrounds was cause for fears of giving, communicating, and mistrust. Skin callus on ring finger remains .... "17 Nearby, also encased behind glass, was a collection of his "artifacts," which included such "ritual objects" as a Rolling Stones album. Luna's performance embodied the conventional construction of Native Americans as a mummified, vanished race, whose productions are to be grouped with animals and minerals, but the signs of contemporaneity in the piece (whether the Rolling Stones album or Luna's own living, breathing presence) disrupted these conventions from within. For unsuspecting viewers, the installation shattered the customary detachment of this cross-cultural encounter. Shocked into recognizing Luna's shared humanity, they were forced to reconsider the assumptions underlying all the other ethnographic displays in the museum. Sophisticated Native American art, implies Luna, is still here and still breathing; it is not an extinct form of natural production.

FRED WILSON. While Luna_worked to expose the racism underlying natural history museum conventions, the New York artist Fred Wilson (b. 1954) was performing similar interventions. Having become interested in museum practices while working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wilson developed his own brand of "curatorial action" that he used at several museums to intervene in the normal course of object interpretation. He was invited in 1991 to spend a year as artist-in-residence at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore, whose director was looking for ways to transform the fusty traditionalism of its displays. Wilson was surprised to discover that the displays at the historical society, located in a city where eighty percent of residents were black, made scant reference to African American history The museum had never before mounted an exhibition about slavery, racism, or the Civil Rights struggle.

After a year of archival research, Wilson's Mining the Museum installation opened, becoming the most popular exhibition in the museum's entire 150-year history Wilson's work for the project did not involve creating new objects, but rather creatively curating the existing objects. He simply reinstalled the museum's collections, redistributing objects from storage to display contexts, rewriting didactic wall texts and manipulating lighting, color, and display architecture. In doing so, he rewrote the museum's history of minority life in Maryland. Wilson's tactics included a straightforward recovery of disregarded historical figures (as in his installation devoted to the Marylander Benjamin Banneker, a freeborn black astronomer of the eighteenth century), but also more complex acts of juxtaposition, as in the "Metalwork, 1723-1880" display, which featured a pair of iron slave shackles nestled among a collection of exquisitely crafted Baltimore silver (fig. 19.18). Arrangements like this transgress the hygienic segregation of artifacts that have structured conventional versions of American history: Wilson's "Metalwork" display reveals a real continuity between the fine arts and the blunter arts of slavery and repression. Other installations reflected upon absences, drawing attention to gaps in the collection. The first room of the exhibition featured a series of six low columns. Three white columns were topped with portrait busts of Henry Clay, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Andrew Jackson (white statesmen with no significant links to Maryland). Three empty black columns were labeled with the names of three eminent African American Marylanders whose absence from the bust collection thereby became conspicuous: Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Benjamin Banneker. By deftly highlighting gaps in the historical society's collection, Wilson illustrated the imperfect construction of history itself. For Wilson, history is an interrogative process that is always open to reinterpretation.

Craft Anachronism

Lin, Luna, and Wilson all refuse to let the past be past. By breaking history out of its petrified memorial forms, each of these artists practices a form of anachronistic critique. By inviting the past to inhabit-even to haunt the present, they argue against the idea of a linear historical progress in which the past is left safely behind. Similar motivations explain the tendency of a surprising number of contemporary artists to use "old-fashioned" media. Despite the proliferating array of sophisticated new digital media available, many artists today have chosen to revive relatively moribund historical media such as silhouettes and embroidery. Drawing upon widespread reconsiderations of craft practice by feminist artists in the 1970s, as well as the important precedent of the AIDS quilt, contemporary artists have rejected the stabilization of these media as docile "heritage arts," bringing them into an active and critical relationship with contemporary culture and politics.

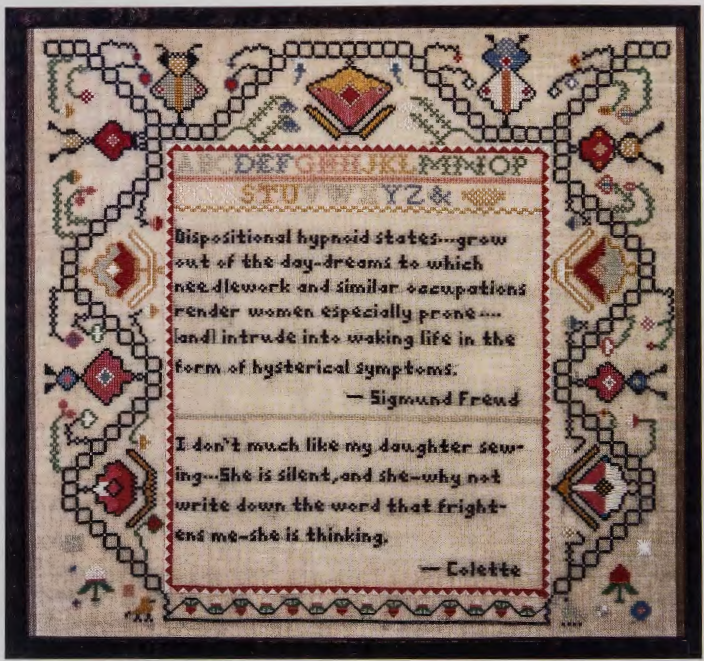

SAMPLERS BY ELAINE REICHEK. Elaine Reichek (b. 1943) was trained as a painter. In the early 1970s, while studying the geometric structure of abstract painting and the textual practices of Conceptual art, she had begun to wonder whether those avant-garde exercises were fundamentally different from the samplers and embroideries that had been produced by women for centuries (see fig. 5.28). When she realized the richness of this question, she decided to devote her entire career to needlework. Reichek produces erudite, witty, and skillful samplers that collapse the gendered hierarchy of art and craft. In one series, she replaced traditional maxims and epigrams with passages from canonical texts (Ovid, Melville, Darwin, Freud, Tennyson, Kierkegaard) that reveal cultural fears about the power of women and needlework. Her 1996 Sampler (Dispositional Hypnoid States) includes quotes from Freud and Colette that worry over the subversive potential of women as they enter the state of deep concentration required by knitting or embroidering (fig. 19.19 ). Reichek based this sampler on an eighteenth-century American design that already seemed to her to embody the darker side of feminine iconography: "the motifs around the border, which are actually florals, have little antennae and seem to metamorphose into insects- a creepy effect out of Kafka ..." 18

In her work and writings, Reichek has demonstrated the inescapable structural connection between needlepoint and the grid-based paintings of artists such as Jasper Johns (see p. 550). She has pointed out that modern computational systems originated in the nineteenth-century textile industry, and that the origin of writing itself is rooted in the history of textiles (the word "text" itself derives from the Latin word texere, to weave). In showing women's work to be at the center of high culture, Reichek does more than simply revive a historical medium. Rather, she uses that medium as the vehicle for a new kind of historical thought. Reichek proposes that history can be rewritten- or rather rewoven-by drawing threads between high and low, women's work and art work, so tightly that they cannot be unraveled.

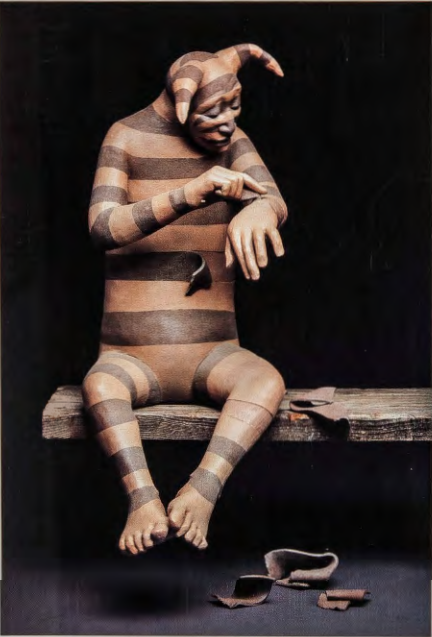

CLAY FIGURES BY ROXANNE SWENTZELL. While many Native American artists work in media like installation and video, others have deliberately chosen materials such as clay, beads, quills, or buffalo hides that have been used in their communities for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. In New Mexico, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, Pueblo potters continue to dig local clay, coil it by hand, and fire it outdoors, much as their ancestors have done since before 1000 C.E. Roxanne Swentzell (b. 1962), a sculptor from Santa Clara Pueblo, sees herself as part of this continuum that stretches back for generations through her maternal lineage. Swentzell operates within the standards of her community's pottery traditions, but also pushes their boundaries. Like her female ancestors, she rolls her clay into long sausage-like forms, and handcoils them to create her work. Yet, instead of building jars or bowls, she creates human forms (fig. 19.20). Some are self-portraits; others, like the one illustrated here, depict the striped Pueblo clown familiar in the art of the Southwest for a thousand years.

Certain male members of Pueblo secret societies paint themselves with the black and white stripes of the clown in order to perform in ceremony. Clowns teach through parody, buffoonery, and bad example (see discussion in Chapter 2). Swentzell's Despairing Clown misbehaves by peeling off his stripes, as if peeling off his very skin. In doing so, the figure (like the artist) interrogates the notion of a fixed Indian identity. Although born from a medium that embodies the deep origins of Pueblo society, Swentzell's figures occupy a Postmodern universe where identity is a matter of detachable surfaces. The irreconcilable tension between the old medium and the new message helps account for the note of melancholy in Swentzell's ostensibly humorous artifacts.

SILHOUETTES BY KARA WALKER. Kara Walker's 1997 installation Slavery! Slavery! (fig. 19.21) revives one of the most popular media of nineteenth-century America: the silhouette (see fig. 6.17). But instead of using the silhouette in its traditional, intimate portrait format, Walker (b. 1969) composes large-scale figures into complex scenes. Upon first viewing, the delicate, winsome outlines of her silhouettes evoke nostalgic associations of a bygone, simpler time. Moss-covered trees recall the moonlight-and-magnolia romance of the Old South, and Walker's composition and design suggest decorative refinement.

Upon closer examination, however, these genteel impressions are quickly dashed. Many of the decorative arabesques in the scene represent abject bodily liquids and gases. The "fountain" at the center flows with spit, urine, and breast milk; kneeling in front of it is a man farting. Other scenes (here and throughout Walker's work) include dismemberment, scatological spectacles, pedophilia, and various other improper sexual acts. Perhaps most disturbingly, in the figures that are meant to be interpreted as African Americans, Walker revives the derogatory stereotypical features of 'blackness" -low brows, large lips, "pickaninny" hair, etc-that have marked the most insidious images in the history of American visual culture. Walker has argued that the silhouette and the stereotype are structurally equivalent: both convey a lot of information with very little means.

Walker's nightmarish antebellum carnivals have been denounced by members of the previous generation of African American artists. In 1997, after Walker became the youngest person ever to win a MacArthur "genius" grant, Betye Saar launched a campaign to protest against Walker's work. Saar and many other artists were appalled by Walker's recirculation of harmful stereotypes; accusing Walker of complicity with the white art establishment that had eagerly embraced her work, Saar claimed that "Kara is selling us down the river."19 Saar, of course, had famously worked with stereotypes herself (see The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, fig. 18.24). But Saar had turned negative images against their creators, reinventing stereotypes as armed allies in the Civil Rights struggle. For Saar and some other artists of her generation, Walker's regressive stereotypes threaten to undo all of the progress they have made.

Walker, however, feels that the long and complex history of stereotyping in America, like that of slavery, has not yet been resolved, and that all Americans are implicated, consciously or not, in the perpetuation of racism. To her mind, the only way to obliterate these stereotypes is to confront us with their lingering presence in our own minds and fantasies. The silhouette art form allows Walker to implicate her viewers in the scenes before them in a way that would not be possible in other media. Most of the figures in her tableaux are life-sized, as if they were shadows thrown by the people standing in the room. This has the imaginative effect of collapsing historical distance and encouraging viewers to think about the persistence of slavery's impact today. Each viewer standing before the work is symbolically implicated in the shadow-play transpiring on the wall. Walker has compared her silhouettes to the Rorschach (ink blot) tests in which psychiatric patients are asked to describe what they see in a series of abstract black blobs against white backgrounds, thereby projecting their own mental states onto the forms. As art historian Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw has shown, the shadow also has a long cultural history as a symbol of repressed evil; the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung (whom we encountered in Chapter 17, pp. 553-4) gave the name of "shadow" to the repressed, socially unacceptable urges that inhabit the individual unconscious. Looming like shadows of America's past, Walker's silhouettes insist that the horrors and degradations of slavery have not been resolved and should not be forgotten.