19.1: Decenterings - The 1980s

- Page ID

- 232376

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)American art of the 1980s drew upon developments of the previous two decades. In Minimalism and Postminimalism, for example, the center or anchor of the work had been impossible to locate; it emerged dynamically at the interstices between object, viewer, and space. This decentered model of meaning applied not only to art but also, increasingly, to artists. In works like Andy Warhol's silkscreen paintings or Mierle Laderman Ukeles's floor-scrubbing performances (see figs. 18.8 and 18.30), the artist's own inner source of creativity was similarly unlocatable. By adopting readymade content and rote, mechanical, or otherwise automatic production techniques, much of Pop and Conceptual art threatened to reposition the artist as a kind of borrower rather than a sovereign creator drawing upon an interior wellspring of genius.

"The Death of the Artist" in Postmodernism

The meaning of artistic creativity was under intense investigation across the humanities and across the globe during the late twentieth century. The transatlantic, interdisciplinary nature of this discussion was evident in the close ties between American art criticism and French literary criticism during this period. The French critic Roland Barthes (1915-80), to suggest just one example, became an influential figure in American art at this time. His 1967 essay "The Death of the Author" challenged the standard mythology of the artist, and became a hallmark of debates over the nature of creativity and the possibility- or not- of true originality.

Barthes argued against the usual tendency to explain works of literature by recourse to the author's biography or internal development. Not only was this simply too easy, he argued, but it also ignored the vast "intertextual" web of sources from which every author must draw while writing. Narrative structures, turns of phrase, even the very words that any writer uses are preexisting elements created by collective cultural systems- they come, in other words, from without rather than within. A piece of literature should be understood as "a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centers of culture."1

Barthes's essay became required reading in the 1980s art world because it helped focus and articulate an array of tendencies that were beginning to coalesce under the term Postmodernism. These included a new interest in the formative activity of reception (as Barthes argued, the work would find its true "origin" not in the mind of the author but rather in the shifting perspectives of its multiple readers), a suspicion of intentionality (the idea that the meaning of a work lies entirely in the artist's intentions), and a new interest in appropriation art (that which unabashedly copies or borrows prefabricated content).

FILM STILLS BY CINDY SHERMAN. Cindy Sherman's photographs exemplified the doubts about selfhood, creativity, and identity that Barthes and others had introduced to the American art world (fig. 19.1). In 1977, Sherman (b. 1954) began to take black-and-white photographs that she called Film Stills. For each of the dozens of images that came to constitute the series, Sherman dressed up and posed herself in settings that recall stereotypical scenes and characters from European and American films. In one she posed as the classic 1950s pin-up beauty, in another the runaway teenager, in others the lush, the office girl, the librarian, etc. Sherman was particularly interested in evoking the look of B-movies-low-budget films that tend to deploy stock characters and predictable stereotypes rather than investing in complicated character development.

Although each of Sherman's photographs is technically a self-portrait, no single self is being portrayed-only a parade of familiar caricatures. There are as many Shermans as there are photographs; she, like the series, is unfinished, fragmented, and arbitrary. In each image Sherman aimed for an expressionless look, as if she were a doll or a robot without internal motivation. This uncanny blankness, as well as the evacuation of identity that it suggests, contributes to the general sense of listlessness that haunts the series. In each image, the protagonist seems immobilized, as if waiting for direction. Indeed, as fictional film stills, Sherman's images adopt a format in which activity is drained out of the image by definition. "The shots I would choose were always the ones in-between the action."2 Something seems always about to happen to the protagonist, who waits for what? Perhaps for the external "reading" that will bring her the meaning that she cannot carry alone.

It was not only their radical deconstruction of identity that made Sherman's Film Stills so influential; it was also their basic status as photographs. During the 1980s, the displacement of individual creativity became increasingly associated with the medium of photography. The rhetoric of mastery and genius that had surrounded auteur photographers of earlier decades gave way to an emphasis on the mechanical production and infinite reproducibility of the photographic image. As a medium whose basic operation does not require extensive training, photography could be seen as part of the "deskilling" of technique that attended so much contemporary art production. For the same reason, it became an ideal medium through which to explore the collapsing distinctions between high art practice and mass media production. Its inherent reproducibility also made it a perfect tool for interrogating the status of originality in art.

Another text that became important for photographers and art critics at this time was the German philosopher Walter Benjamin's 1936 essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," which argued that photography tended to confuse the distinction between the original and the copy. Compared to traditional media like painting, Benjamin (1892-1940) argued, there is no meaningful concept of the "original" in photography. However fanatically collectors might chase after vintage prints, it makes little sense to seek a single authentic print from a negative that can always yield new ones. All prints are equally secondary. All photographs, in other words, are already copies.

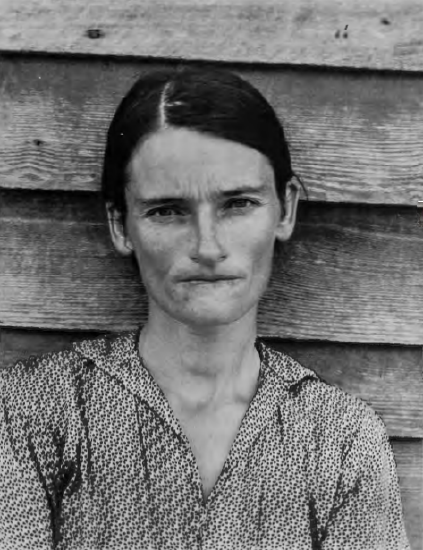

SHERRIE LEVINE'S REPHOTOGRAPHS. In the early 1980s Sherrie Levine (b. 1947) took a series of photographs that brazenly asserted the status of photography as reproduction. A typical example from the series is Untitled, After Walker Evans (fig. 19.2) of 1981. At first, nothing about the picture seems amiss; it is a searching, beautifully composed portrait. But Levine's photograph is, in fact, a photograph of an existing photograph- a 1930s documentary image taken by Walker Evans (1903- 1975) of the sharecropper's wife Allie Mae Burroughs (see fig. 16.23). In this act of appropriation, Levine reproduced Evans's image without altering it, and exhibited it in such a way that only the title acknowledged anything about its "original" authorship. As the critic Douglas Crimp wrote, Levine "merely, and literally, takes photographs."3

Levine's act of rephotography, however simple it may have been as a technical operation, raised all sorts of complicated questions about the general possibility of originality and about Evans's originality in particular. For if we agree that Levine's photograph is merely a copy, what, we must next ask, is it a copy oft It isn't exactly a copy of Evans's photograph, because Levine aimed her camera not at an original photographic print, but rather at a photomechanical reproduction printed in a book. So her photo is really a copy of a copy; and since even the "original" print was itself a copy (as Benjamin would have it), Levine's is then a copy of a copy of a copy. Once this reverberation of copying has been set into play, it becomes possible to see that even Evans's original vision for his photograph-for example, the flat background that creates a direct connection between sitter and viewer, the cropping and composition that focus attention on the face-is itself derived from the long tradition of religious icon painting that has provided the ultimate model of portraiture in the West for millennia. Evans's "original" photograph, in other words, is itself a collection of copies, a "tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centers of culture." Levine's objective in copying Evans was not simply to announce that she was a copyist (that much was obvious), but also that Evans, despite all of the rhetoric of documentary immediacy surrounding his work, was also a copyist. As a favorite catchphrase of the day put it, "underneath each picture there is always another picture."4

Levine's work was not a personal attack on Evans; it was a critical statement concerning visual culture in general. Her rephotographs dramatized the process of appropriation, reproduction, and re-use that distinguishes the entire history of art. Photography, for Levine, is merely a more conspicuous model of the borrowing and reproduction that haunt all representation and all "expression"; all artists share the same heritage of appropriation and inauthenticity. Levine's critique of the originality of the work of art, moreover, was analogous to the critique of the centered and original self that Sherman explored in her "self" portraits. Just as Barthes had argued that there is no original point of authorship lurking at the core of a text, but only echoes of language itself, so is all identity understood as constructed from borrowed self-images. As Crimp put it in reference to appropriation artists like Levine, "In their work, the original cannot be located; it is always deferred; even the self which might have generated an original is shown to be itself a copy."5

1970s Feminism vs 1980s Feminism

IT IS NO ACCIDENT that women like Sherman and Levine played prominent roles in deconstructing the art world pieties of genius and originality. Most of the "original geniuses" and "masters" in Western art had been, after all, defined categorically as men. Feminist artists had an outsized role in defining the Postmodern emphasis on the external construction of identity and the impossibility of the centered self. But these new understandings of the self also altered the development of feminism and led to a rift within the community of feminist artists.

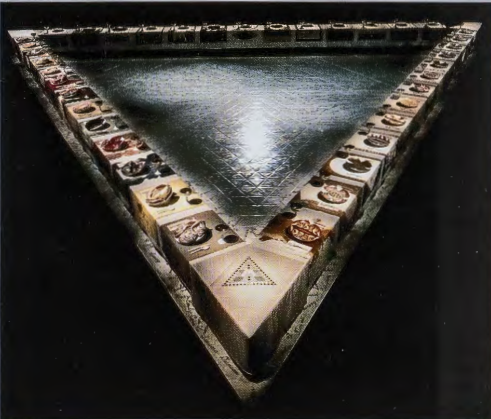

The most prominent and influential feminist art of the 1970s had insisted upon creating positive images and practices out of the traditionally devalued terms of womanhood. It seized upon aspects of femininity that have historically been understood as weak, passive, or empty (the intimate, infolded biology of the female reproductive organs, the mythical history of women's close relationship to nature and to the earth, and the ancient practices of domesticity, craft, and "women's work"), and inverted them into images of strength. This frequently involved reimagining the history of civilization from a "gynocentric" perspective. Judy Chicago's (b. 1939) famous installation The Dinner Party of 1974-9 did just this. At a large triangular dinner table, she and her team of collaborators made place settings for women whose talents had been marginalized throughout history. Each "plate" evokes the woman in question with a blatantly vaginal/floral ceramic object (fig. 19.3). Chicago, in an obvious allusion to the Last Supper, "sets a place" for women at the world-historical table. The plates celebrate, rather than disavow, the feared and despised elements of feminine anatomy and creative production.

Chicago's work accepts the unique cultural and biological status of women, and seizes upon femininity as a platform for collective action. By the 1980s, however, this strategy was coming into conflict with the new critiques of stable selfhood. The new brand of feminism that was emerging in the work of artists like Cindy Sherman positioned femininity- indeed, gender itself-as socially constructed rather than biologically essential. Although the distinctions between essentialist and constructionist feminism were hardly absolute, 1980s feminists often felt that their 1970s precursors had slipped into a restrictive biological determinism. Another critique was that 1970s feminists had proposed a false unity among all women, ignoring social, cultural, and economic differences (the differences between the experiences of white and black, or upper- and working-class women, for example) that cannot be explained biologically but can be analyzed politically.

1980s feminists refused to posit any essentially feminine qualities. They argued that the very concept of "the feminine" had emerged from patriarchal social systems in order to provide an opposite and subordinate term to all that was masculine. Hoping to disrupt this social binary, they defined femininity not as a real quality but rather as a masquerade or a performance, a detachable costume that anyone, male or female , could shed and change at will. They worked on both the visual and theoretical level to analyze and expose the codes and stereotypes of gender polarity. This new model had an activist dimension - if femininity was merely a construction, after all, then it was certainly available for deconstruction. But many 1970s-era feminists felt that the new model was damaging. Many even argued that it was insidious, for it questioned the very possibility of identity at precisely the moment that women and other disenfranchised groups had begun to assert their power and autonomy.

POSTMODERN THEORIES OF REFERENCE. According to the logic of Levine's photographs, the viewer has no access to the plenitude and truth of the thing shown (in this case, Allie Mae Burroughs). One looks instead at a picture that sits, in a sense, atop an infinite stack of other pictures, references, and copies. ''Allie Mae Burroughs" can simply never be reached (in period parlance this was known as "the flight of the referent"). This model of representation denies the possibility of any access to reality-indeed, it denies the possibility that any knowable reality exists outside the act of representation. Many theorists and philosophers who came to prominence during the late 1970s and 198os-Jean Baudrillard (b. 1929), Fredric Jameson (b. 1934),Jacques Lacan (1901-81),Jacques Derrida (1930---2004), Michel Foucault (1926-84), and others-offered versions of this argument. This belief that there is no "deeper" meaning 'behind" representations (representations and signs being all that there are) was one of the guiding rubrics of Postmodernism.

While some understood Postmodernism as a philosophical truth (i.e., humans have never had access to reality) it was equally common to view the Postmodern as a historical condition. In this version, as articulated by the critic Fredric Jameson, the late twentieth century was an era of "late capitalism," in which the global proliferation of mass media and the commodification of experience left no authentic, original, or individual space uncolonized. As the painter and theorist Thomas Lawson (b. 1951) wrote: "the insistent penetration of the mass media into every facet of our daily lives has made the possibility of authentic experience difficult, if not impossible .. .. Every cigarette, every drink, every love affair echoes down a never-ending passageway of references-to advertisements, to television shows, to movies-to the point where we no longer know if we mimic or are mimicked."6

POSTMODERN PASTICHE IN ARCHITECTURE. Many theorists of Postmodernism had been inspired by Warhol's silkscreen paintings (see fig. 18.7), where replicated images, seeming to float atop a shallow surface, refuse access to an "interior" meaning or content. Indeed, although Postmodern theories of pictorial representation came to critical fruition in the 1980s, their continuity with the image recycling of Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and the Pop artists twenty years earlier was clear. The advent of Postmodernism in the realm of American architecture, however, was more jarring, for it rudely interrupted the preeminence that the International Style had enjoyed throughout the mid-century period (see Chapter 17). The AT&T Building (now the Sony Building), completed in Manhattan in 1984 (fig. 19.4), was a bellwether of the new architectural paradigm. Its departure from formula was surprising because it was designed by Philip Johnson, who had been one of the curators of the groundbreaking 1932 Museum of Modern Art exhibition The International Style and one of the most prominent American advocates of the purist Modernism of Mies van der Rohe (see fig. 17.31) during the middle of the century.

The AT&T building evokes multiple design styles and historical periods at once: gigantic arches along the base of the building recall a Renaissance chapel by Brunelleschi, the broken pediment at the top evokes eighteenth-century Chippendale highboys, and the fenestration pattern along the sides resembles a Rolls Royce radiator grille. Whereas the International Style had shunned historical reference in favor of an elegant, universal functionalism, here were historicism and referentiality with a vengeance. True to the new models of referential superficiality espoused by Postmodernists, these historical signals function ornamentally. They are not pure, nor are they rigorous revivals of historical techniques or forms: they are "stuck on" to the building, forming an unapologetically flamboyant pastiche.

Art and Language

If Postmodern models of the image rejected the notion that pictures provided clear, unfettered access to the referents "behind" them, Postmodern models of text did the same. Many artists of the 1980s, producing works that were based primarily in text and typography, explored the opacity of language. By fostering doubt about the objectivity of text, they demonstrated that language is not a neutral carrier of information, but rather a supple tool for the creation and perpetuation of power relationships. They aimed to expose the hidden politics lurking beneath ostensibly neutral language.

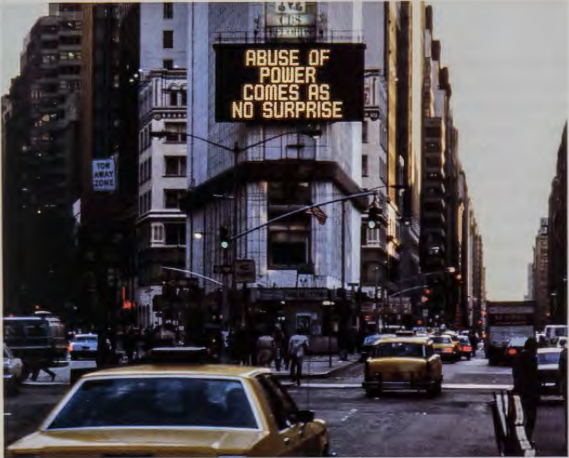

JENNY HOLZER. In a career spanning from the 1970s to the present, Jenny Holzer (b. 1950) has aimed to disrupt the apparent objectivity of "common language." For her Truisms project, produced between 1979 and 1982, she wrote short statements that resembled commonsensical aphorisms but carried disturbingly sinister, violent, or cynical messages: 'Absolute submission can be a form of freedom"; 'Abuse of power comes as no surprise"; "Enjoy yourself because you can't change anything anyway." She then disseminated the statements throughout Lower Manhattan on cheap offset posters; soon she had them appearing on T-shirts, hats, pencils, electronic signs, and even condom wrappers. In 1982, they were flashed at 40- second intervals to a mass urban audience on the enormous Spectacolor board in Times Square (fig. 19.5).

Holzer crafted the Truisms so that they would seem to have been issued by an anonymous common voice rather than a particular individual. She wanted them to appear to emanate from the genderless, ubiquitous "they" in the phrase "you know what they say." As Holzer said, "I find it better to have no particular associations attached to the 'voice' in order for it to be perceived as true."7 The illusion of anonymity, in other words, begets the illusion of unanimity. Yet even as she established this illusion, she immediately undermined the Truisms' truth value by riddling them with contradictions (one Truism will often contradict another). And by pushing each of them just beyond the edge of generally acceptable sentiments (for example, "Bad intentions can yield good results"), Holzer jarred her viewers out of their customary passivity in the face of public pronouncements. She hoped that this would set up a resistance, however small, to the suggestions of mass communication that were normally accepted unreflectingly. As described by the critic Hal Foster, "coercive languages are usually hidden, at work everywhere and nowhere: when they are exposed, they look ridiculous."8 Ideally, this exposure causes viewers to question all the other messages (especially advertisements) surrounding them in common space. In her momentary disruption of a cultural operation that normally functions imperceptibly, Holzer builds upon the strategies of Conceptual artists of the 1970s (see figs. 18.17, 18.19), who were also revealing the distortions within systems of language.

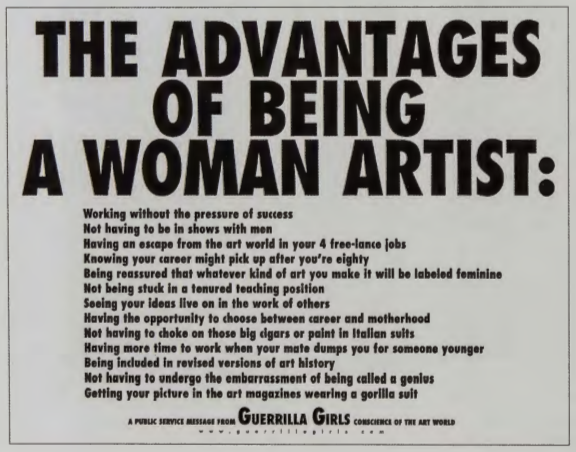

GUERRILLA GIRLS. Other artists hijacked the seeming objectivity of institutional language in order to smuggle disruptive messages into the public sphere. In 1985, a series of mysterious "Public Service Messages" began appearing in art magazines and on Manhattan streets, buses, and subways. In stark, affectless black type, using lists and statistics, the posters exposed the biases of prominent art institutions. The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist (fig. 19.6) dispassionately enumerated the absurd discrimination still facing women artists in 1989. In Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?, the text noted that women made up less than five percent of the artists shown, but eighty-five percent of the nudes. Who had created these posters? They bore only the enigmatic attribution "Guerrilla Girls: Conscience of the Art World."

When groups of people answering to that description began to appear in public at lectures and press events, they kept their identities concealed behind gorilla masks. The pun on guerrilla / gorilla was typical of the group's wordplay. But despite the humor of their subversions, the group's need to resort to guerrilla tactics served as testimony to the strength of the forces arrayed against them. During this period of conservative retrenchment (see pp. 635-6), feminism had been defanged. Feminism was often perceived as embarrassing; the dissatisfactions of women were interpreted as if they were symptoms of personal hysteria rather than rational responses to real conditions. The businesslike rationality and statistical acumen of the Guerrilla Girls' text works helped disarm this critique. So, too, did their anonymity. Like Holzer's Truisms, their voiceless texts projected an air of commonsensical validity.

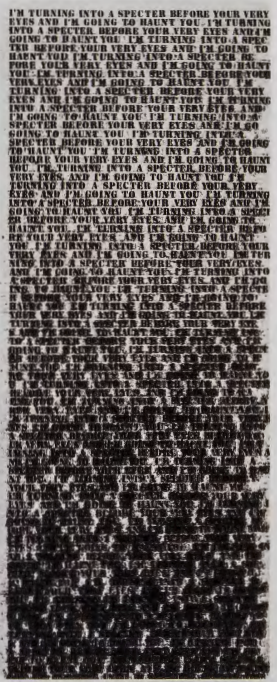

GLENN LIGON. Glenn Ligon's textual paintings explore the power of language to obscure, rather than enable, communication. In his 1992 Untitled (I'm Turning into a Specter Before Your Very Eyes and I'm Going to Haunt You) (fig. 19.7), Ligon (b. 1960) used a black oilstick and hand stencil to repeat, line after line, a phrase adapted from Jean Genet's 1958 play The Blacks. As the words spill down the canvas, the stenciling becomes less and less precise, until the phrase becomes so blotched, smirched, and smudged as to be virtually illegible. Like Jasper Johns's Gray Numbers (seep. 550), the painting emphasizes the material weight and heft of writing. One looks at Ligon's text, not through it. The painting refuses the notion of language as a transparent tool for the conveyance of meaning, producing instead an effect of blockage and opacity. This is further emphasized by the size of the canvas, 80 X 32 inches, which is precisely the dimension of a standard doorway. Thus the painting sets itself up as a threshold, a space for passage and communication, but becomes instead a barricade of language.

As a black artist who grew up in the Bronx at the height of the Civil Rights struggle in the 1960s, Ligon was particularly interested in the language barricades that the haunting legacy of racial discrimination imposes upon African Americans. Even if outright slavery has ended, its effects still resound in the English language. How are black Americans to communicate when using a language that defines them negatively and oppositionally, as the non-white, the not-quite-human? How are they to communicate when they do not yet have full status as free speakers? Ligon's work exposes these difficulties; the reader's struggle to make sense of the clotted letters parallels the speaker's struggle to be understood.

Consumption, Critique, and Complicity

Postmodernism suggested that "original" expression is wholly derived from existing cultural systems. When added to the growing suspicion that, in the era of late capitalism, the existing cultural system was wholly determined by market values and consumer behavior, an unprecedented debate arose about the collapsing distinction between art and commerce. While avant-garde art had, throughout the century, attempted to oppose commercialism from the outside, it now seemed that there was no longer any expression-much less any art expression-free from the taint of market values. Given this situation, many artists felt that rather than attempt to find a space outside capitalism from which to attack it, they might do better to explore a complex and subversive complicity, penetrating the system in order to expose and thereby destabilize its otherwise invisible functions. As the artist Barbara Kruger (b. 1945) put it, "I wanted [my work] to enter the marketplace because I began to understand that outside the market there is nothing-not a piece of lint, a cardigan, a coffee table, a human being."9

HAIM STEINBACH. Haim Steinbach (b. 1944) made "commodity sculptures" in which he arranged shiny store bought objects on clean, minimal, laminated shelving (fig. 19.8). Featuring everything from Yoda masks to toilet brushes, the installations combine the strategies of Pop, Minimalism, and the Duchampian readymade. Steinbach's work equates artistic production with the practice of appraising, choosing, purchasing, and displaying- the major activities of consumer society: "What I do with objects is what anyone does ... with objects, which is talk and communicate through a socially shared ritual of moving, placing, and arranging them."10 Contemporary identity, for Steinbach, is a product of consumption rather than production. It is not developed from within but rather patched together out of brand affiliations and consumption choices made in the marketplace.

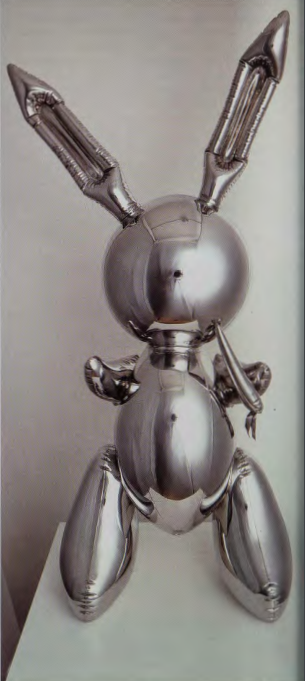

JEFF KOONS. Jeff Koons (b. 1955) produced vexing sculptures that expose the strangeness of a world in which art has become a commodity and commodities have become art. His sculpture has qualities associated with cheap products that are designed to attract consumers gleaming, shiny surfaces, seductive bright colors, and kitschy, popular, or sentimental subject matter. But his pieces are typically rendered in heavy, permanent materials, expanded to a looming scale, or otherwise presented as if they are monuments to the achievements of Western civilization. His most iconic work of the 1980s was Rabbit of 1986 (fig. 19.9), a solid stainless steel cast of a child's popular blow-up Easter toy. The toy's transformation into steel grants permanence to a fleeting, obsolescent consumer object, but also changes the character of that object in unsettling ways. In the process of casting, the air in the toy was heated, so the final sculpture has an especially taut and distorted shape, its seams straining as if it were about to explode. Koons produced several other sculptures that used a paradoxical blend of gravity and buoyancy to explore the contradictions of late capitalism's merger of art and the commodity; these featured inflatable rescue devices like rafts and life vests cast in heavy bronze. Each of these works lent art world gravitas to the effervescent, inflationary quality of the American economy, but hinted that both worlds might thereby sink.

Although these sculptures had a critical element, Koons was frequently accused of exploiting, rather than resisting, the logic of consumer capitalism and its speculative bubbles. He certainly knew that logic well as he spent six years as a commodities trader on Wall Street before turning full-time to his art. He was a savvy self-promoter, introducing each new series of sculptures with glamorous advertisements. He produced eminently saleable luxury objects- and they sold briskly-just as a boom in the 1980s art market sent prices skyrocketing. The perfect ambivalence of Koons's work-was it cynical or oppositional?-made him a test case for art criticism of the 1980s, much of which devoted itself to making increasingly fine-grained and difficult distinctions between critique and complicity among artists whose work engaged the theme of consumption.

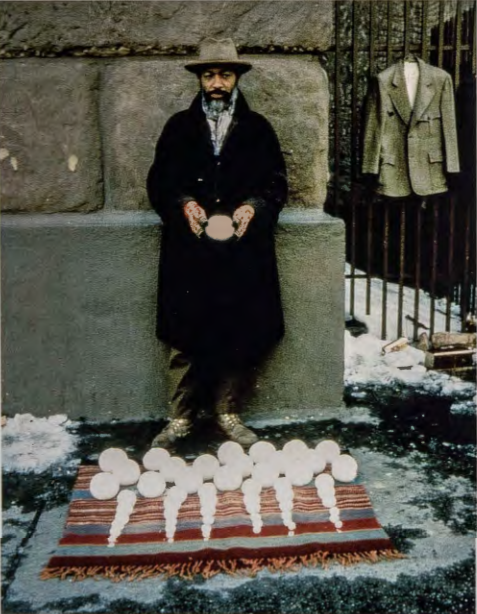

DAVID HAMMONS. More unambiguously critical was art that approached the culture of consumption from the standpoint of the dispossessed. David Hammons (b. 1943) held his Blizzard Ball Sale in 1983 on a cold Manhattan street corner (fig. 19.10). Working and living in Harlem, Hammons was known in the 1980s for work that reflected both the deprivation and the ingenuity of African American material culture in economically stagnant urban areas. He had previously lived in Los Angeles, where he was inspired by Melvin Edwards's Lynch Fragments made of scavenged steel (see fig. 18.13); his own work made use of even baser materials such as hair, grease, and paper bags. For the Ball Sale he formed street snow into near-perfect spheres of variable sizes and arranged them for sale to passersby. Like Steinbach and Koons, Hammons is explicit about the commodity context of his art-he is, after all, hawking his work on the street. But his model of salesmanship is hardly Koons's white-collar enterprise of finance and slick advertising. It is closer, instead, to the face-to-face haggling that characterizes bootstrap, street-level commercial exchange in the inner city. Like Koons and Steinbach (not to mention Warhol), Hammons offers an array of consumer choices: his snowballs come in several different sizes, carefully arranged in "product lines." He thus mimics the way the American economy stimulates consumption by offering an abundant selection of slightly different products, but he also signals the patent superficiality of all such illusions of choice. When it comes right down to it, it is all just snow. Like Koons and Steinbach, Hammons makes saleable objects, but his will serve rather poorly as durable private property. In fact, the point of sale is also the point of destruction, since in handling and carrying the snowballs, any "collectors" would either throw them or cause them to melt.

It is this very delicacy that matters most in Hammons's sale. Everything about it is liminal and tenuous: only the finest of material and conceptual distinctions separate these artworks from worthless urban detritus. A small folded rug is all that separates Hammons's handiworks from the slush on the sidewalk from which, one presumes, they originated. This is definitely "commodity sculpture," but it speaks of a world in which the exchange of commodities represent not the promise of accumulation but rather the thin line between survival and desperation. Note that there are other "sales" going on around Hammons's; people have set out makeshift tables to sell products that are nearly as heartbreakingly worthless as snowballs.

Despite its "low" materials and locale, Hammons's sale reflects upon the most refined art trends of the twentieth century. Its liminality suggests not only the poverty line but also the conceptual line-first limned by Duchamp with his readymades-between art and everyday objects (see fig. 13.11). Its pure geometric forms mimic abstract sculpture generally, and Minimalism specifically; especially in their meticulous layout, serial repetition, and ground-based presentation. The elements of absurdism, performance, obsolescence, and audience participation recall Happenings and Fluxus events. As "sale art," it evokes Pop and particularly Oldenburg's The Store (see fig. 18.3). For Hammons, both art and economic life are tenuous. He explores the economies of desperation that spring up around the edges of affluence-scavenging, recycling, and repurposing-and adopts them as art practices.

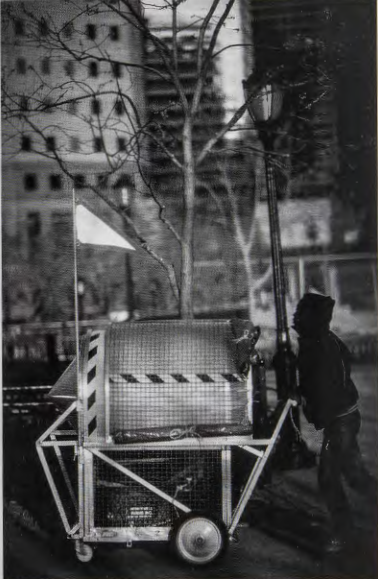

KRZYSZTOF WODICZKO. These liminal economies were also addressed by Krzysztof Wodiczko (b. 1943), a Polish artist who had recently immigrated to the United States. In 1988-9 he developed and tested a series of prototype Homeless Vehicles in Manhattan (fig. 19.11). In New York, severe cutbacks in funding for public housing, new development policies favoring the destruction of low-income neighborhoods for corporate development, and the wholesale deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals had led to a drastic increase in homelessness. And yet the homeless seemed to remain invisible. They were frequently evicted from public spaces or simply ignored through workaday acts of neglect, as other citizens sidestepped them on the streets.

Wodiczko's Homeless Vehicles were designed to ameliorate the most pressing problems of the homeless and, simultaneously; to force those problems back into public visibility. Designed in active consultation with homeless people, the vehicles were part sleeping pod, part security capsule, part recycling cart, and part aerodynamic symbol of the perpetual movement that defines the state of homelessness. They gave concrete shape to the struggle for survival in the city. In doing so, they interrupted the existing consumer order. From a classical economic perspective, it is absurd to design and manufacture specialized equipment to meet the needs of the destitute. After all, in a consumer society, products are designed only for those who have the resources to buy them. Wodiczko, who had worked for many years as an industrial designer in Warsaw, considered his project to be an example not of traditional product design but instead of "interrogative design," which draws attention to problems and serves as "a point of convergence that concentrates a plethora of embarrassing questions." 11 Therefore, while the vehicles served as temporary palliatives for their homeless users, they were also intended as an irritant to the city at large, which was forced to notice these gleaming symbols of the scandal of homelessness.

JAUNE QUICK-TO-SEE SMITH. Native American artists were in a position to make particularly nuanced contributions to the period's debates about American consumerism. Jaune Quick-To-See Smith (b. 1940), of French Cree, Flathead, and Shoshone descent, came from a family of nomadic horse traders. Her 1992 work Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People) (fig. 19.12) drew its visual vocabulary from the Indian rock art of Montana, the prehistoric paintings of Lascaux, the abstracted figuration of Plains ledger drawings, and the amalgamation of painting and collage in Robert Rauschenberg's work (see fig. 17.17). The heavy red paint that layers the surface drips down like blood, an indictment of the so-called "exchange" between Native and non-Native.

Smith's painting features a huge canoe of the type used for trading expeditions; strung above it are the "gifts" of the title. These are not Native-made items, but the kitsch to which Indian identity has been reduced: fake headdresses and arrow quivers, a plastic Indian princess doll, a Red Man tobacco tin, Washington Redskins and Atlanta Braves baseball caps, and cheap beaded belts made in China or the Philippines. This work was made in 1992 as a commentary on Columbus's journey to the Americas in 1492-the year that the Native American "market" was first opened to Europe and a year that Smith has sardonically called "the year that tourism began." Whereas the stereotypical 'beads-for-Manhattan" fable envisions white men snickering as they trade trinkets for huge tracts of land, Smith here imagines the inversion of that situation. Now it is white people who are entranced by cheap plastic gimcracks. Smith's work also followed closely upon the passage in 1990 of an important Federal law- NAGPRA, or the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act- which compelled American museums to return (or "repatriate") Native remains and sacred objects to Native groups if requested. Smith's work suggests a kind of reverse repatriation. The commodities attached to the painting serve certain sacred anthropological purposes for whites but do not belong in Native value systems. So Smith offers to give them back to the American museum world.

The Culture Wars

In 1980 the United States entered a phase of political and cultural conservatism signaled by the election (and, in 1984, the reelection) of Ronald Reagan as president. Reagan's administration corresponded with a widespread backlash against feminism, civil rights, gay rights, and many other socially progressive trends of the 1960s and 1970s. Reagan's financial policies (popularly called "Reaganomics") emphasized tax cuts and a general reduction in governmental economic regulation, encouraging the expansion of large corporations and the consolidation of individual wealth. Both the cultural and the fiscal conservatism of the Reagan years had a direct impact on the American art world. On the one hand, the Reagan economy stimulated a boom in the art market, while on the other hand, its tone of social conservatism antagonized artists who did not hold to its definitions of art and propriety. By the early 1990s, the hostility between the conservative establishment and the art world had erupted into a full-blown "culture war."

At the same time, the highly theoretical basis of much advanced art in the 1980s contributed to a broader disconnection between the art world and mainstream culture. For many Americans, art had begun to seem overly rarefied and "difficult," out of touch with commonsense aesthetics. In the polarized cultural climate of the time, there were few incentives to bridge the gap between the intellectual vanguard and an increasingly alienated mainstream audience. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, this misfit became evident on many levels. Most troubling was a series of highly publicized clashes between artists and conservative religious organizations in the late 1980s.

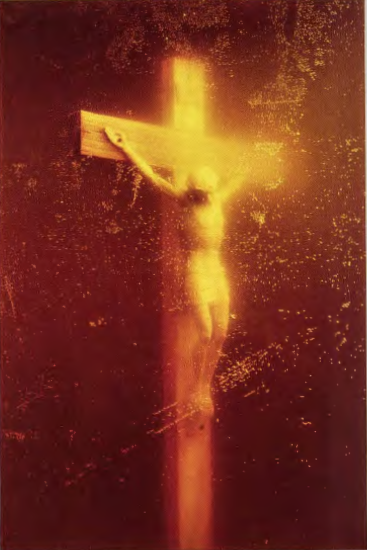

ANDRES SERRANO'S PISS CHRIST. In 1987, Andres Serrano (b. 1950), a Brooklyn artist of Honduran-Afro-Cuban ancestry who had spent a troubled childhood taking refuge among Renaissance religious paintings at the Metropolitan Museum, exhibited an altarpiece-sized photograph showing a crucifix surrounded by a luminous, ethereal glow (fig. 19.13). The controversy lay in the fact that the photograph was titled Piss Christ, and that Serrano had produced it by immersing a small plastic crucifix in a Plexiglas tank of his own urine. When Donald E. Wildman, leader of the Christian decency group the American Family Association, found out about the photograph, and learned that Serrano had previously received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, he sent a protest letter to every member of Congress and encouraged his followers to do the same. This resulted, eventually, in the conservative legislator Jesse Helms calling Serrano a "jerk" on the Senate floor, and begging his supporters "to stop the liberals from spending taxpayers' money on perverted, deviant art."12

Serrano had been photographing bodily fluids such as blood, milk, and urine in tanks for some time, interested in their abstract formal beauty as well as their complicated relationship to the Catholicism with which he grew up. He was interested in Catholicism's deep ambivalence about the body. As he put it: "The Church is obsessed with the body and blood of Christ. At the same time, there is the impulse to repress and deny the physical nature of the Church's membership. There is a real ambivalence there ....In my work, I attempt to personalize this tension in institutional religion by revising the way in which body fluids are idealized."13 Such ambivalence, however, was drowned out by the fervor of religious outrage that followed. Serrano had intended his photograph to be provocative, but he did not count on such a broad audience among Americans outside the art world. This audience approached the photograph (or, rather, reproductions of it) without any knowledge of Serrano's larger body of work, nor, generally, with any understanding of the traditions of Body art, Assemblage, and Postmodernism that might have permitted a more nuanced understanding of the image. Whereas Postmodernism modeled the photographic image as a juxtaposition of mere signs without any real connection to the things represented (Serrano's obviously cheap plastic crucifix emphasizes the superficial status of the picture as a whole), many politicians reacted to the image literally, as if Serrano were actually pissing on Christ.

Added to the problem was the fact that bodily fluids in general had taken on a highly political charge by the late 1980s. The AIDS crisis had erupted, and it had become evident that HIV could be spread through the blood and other bodily fluids. Bodily fluids thus conveyed connotations of confusion and fear, and became associated with the conflation of homosexuality and toxicity. Urine was also politically charged, since, in Reagan's "War on Drugs," debates were raging about the constitutionality of routine drug testing. The battles over Serrano's photograph thus came to be about much more than art or even religion-at stake for both sides was the freedom or restriction of bodies in a context of fear, uncertainty, and misunderstanding.

CONTROVERSIES OVER PUBLIC FUNDING. Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, several similar controversies erupted over federally funded art. Works deemed obscene or offensive, notably Robert Mapplethorpe's photographs of gay men engaged in sadomasochistic activities, were loudly and frequently denounced in Congress. Even abstract sculpture became controversial, as in the case of Richard Serra's federal art commission Tilted Arc, a 12-foot-high steel slab installed across the courtyard plaza of the Jacob Javits Federal Building in New York. The work was removed and destroyed in 1989 after protracted public hearings. Serra (b. 1939), working with the language of Postminimalism, had placed the sculpture in the open plaza in such a way as to force pedestrians to walk long detours to enter the building, thus drawing attention to the impact of physical objects on the bodily experience of public space. He wanted pedestrians to attend to the subtle perceptual changes that the sculpture created. But the language of Postminimalism did not translate clearly to the everyday lives of federal workers, many of whom resented being lectured to about phenomenology and felt that the piece was ugly and aggressive.

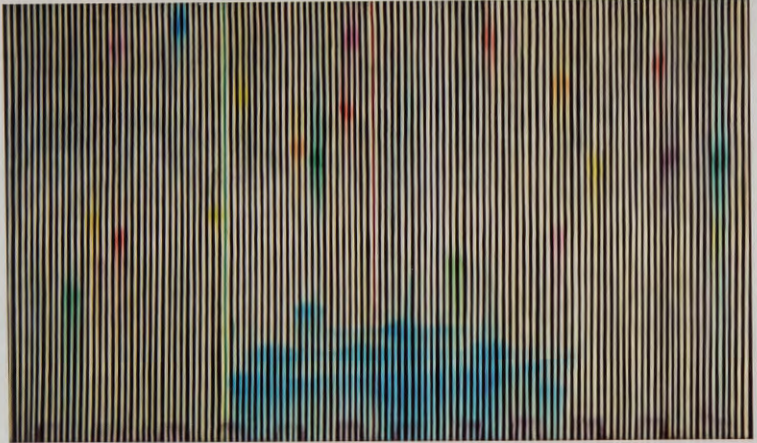

THE AIDS CRISIS. Although the culture wars were fueled by political differences and mistranslations between traditional ideas of art and the theoretical notions current in the art world, some art did manage to straddle this barrier. Ross Bleckner's (b. 1949) paintings (fig. 19.14) were made according to the logic of the Postmodern "flight of the referent." They lie somewhere between abstraction and representation-they look like dim and fuzzy representations of faraway abstract paintings, and have the melancholy air of the Postmodernist's inability to reach through the surface of pictures to something true and concrete below. They are beautiful, unthreatening, and unapologetically romantic, and they sold well in the gallery boom of the 1980s. But at the same time they are deeply political: they function as mourning pictures for Bleckner's many friends who had died of AIDS. In Bleckner's paintings, the postmodern "retreat of the real" paralleled other, more immediate losses.

The NAMES Project AIDS quilt (fig. 19.15) was a collective protest project born of grief and anger. But because it took the form of a quilt-perhaps the most comforting form of American art possible-it did not have the immediately polarizing effect that some other AIDS related art did in the 1980s. In 1985, when AIDS was still thought to be a disease limited to the male homosexual community; many either ignored AIDS deaths or claimed that they were justified punishments for the practice of homosexuality. Cleve Jones (b. 1954), a San Francisco gay activist who had recently been viciously stabbed by a homophobic gang and was facing his own death from AIDS, wanted to produce a memorial for the thousands of people who had already died. But in order to do so, he knew that he needed to find a way to break through the hostility and fear surrounding the disease so that the dead might be treated with empathy and respect: "I was just overwhelmed by the need to find a way to grieve together for our loved ones who had died so horribly, and also to try to find the weapon that would break through the stupidity and the bigotry and all of the cruel indifference that even today hampers our response."14 He remembered the cherished quilts that his grandmother and great-grandmother had made in his hometown of Bee Ridge, Indiana, and immediately he hit upon the idea of the AIDS quilt. As he relates in a recent interview (the development of triple cocktail AIDS drugs in the late 1980s saved his life): "I thought, what a perfect symbol; what a warm, comforting, middle-class, middle-American, traditional-family-values symbol to attach to this disease that's killing homosexuals and IV drug users and Haitian immigrants, and maybe, just maybe, we could apply those traditional family values to my family."15 He realized that a work of public art about AIDS in the format of a familiar domestic icon might jar Americans into acknowledging the humanity of the dead.

He invited others to contribute to the quilt and, within two years, some 1900 panels commemorating the lives of people who had died of AIDS were exhibited on the Mall in Washington, D.C. By 2003, over 45,000 panels memorializing some 82,000 individuals had been added; more are submitted each month. Each quilt block is made up of eight 3 X 6 foot panels, each of which, in turn, mimics the size of a coffin-a fitting format for a funerary monument.

The AIDS quilt makes the collective loss immediate by recording the individual names of the dead. Just as the nineteenth-century quilter Elizabeth Roseberry Mitchell recorded the names of her dead sons on tiny coffins in her graveyard quilt which honored her whole family (see fig. 8.5), the AIDS quilt honors both the dead and the bereaved who made the panels. The NAMES Project Archive has kept meticulous records of these individuals, including photos, letters, and personal statements. The work was last seen in its entirety in 1996, when nearly 40,000 panels covered the full eleven-block expanse of the Mall in Washington-the largest urban public space in the entire United States. Having now outgrown the Mall, the quilt is exhibited in portions. At every installation site, the ritual of remembrance is enacted by unfolding and laying down the quilt blocks and reciting the names of the dead.