19.3: Contemporary American Art and Globalization

- Page ID

- 232378

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Globalization is a complex phenomenon that often seems to exist only as the sum total of a handful of contemporary catchwords-"de-territorialization," "nomad.ism," "transnationalism," "diaspora," "consolidation," "connectivity," "liquidity." Behind each of these terms, however, lies a common connotation of movement, exchange, and communication. Globalization can be considered, most broadly, as a worldwide process of translation-translation achieved by establishing common codes and languages between previously isolated entities. Given this broad emphasis on translation, we need not think of globalization as belonging only to the economic sphere; it is also a technological, biological, and, of course, a geopolitical force.

It is standard practice to view globalization in economic terms: separate national economies are linked through standard systems of trade and monetary variables so that transnational exchange can take place easily. The Euro, for example, provides a common unit of exchange that allows relatively unfettered trade between different nations of Europe. The globalization of the economy is producing the rapid consolidation of trade networks, speeding the flow of information and resources across national boundaries, producing a steep rise in outsourcing and other transnational business practices, and exposing local cultures and value systems to the homogenizing pressure of a single global economy. The ultimate implications of this process are now a subject of intense debate, but one possible outcome is the retreat of the nation-state and the rise of the corporation or conglomerate as the basic unit of geopolitical identity and power.

Globalization can also be understood technologically. Economic consolidation is closely linked with the development of digital technologies, which function by reducing all information, whatever its form, into a binary code. This permits the mobility and interchangeability of all information, regardless of its original medium of inscription; thus college students can now listen to wax-cylinder sound recordings by Thomas Edison and the soundtracks of recent Hollywood films in rapid succession on a single media player. Differences in form and medium are obliterated for the sake of easy transfer and broad dissemination. Also sharing in this process of transcoding is the current revolution in genetic engineering, for it allows the migration of genetic information between previously separated groups and species. In essence, by opening up new means of communication, grounds of similarity, and avenues of equivalence and exchange, the process of globalization transposes the location of "encounter" into new spaces- mobile, monetary, and microcosmic. American art today reflects both optimism and anxiety about these changes.

Nomads

Few works have focused debate about the art world implications of globalization as intensely as the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (fig. 19.22). Bilbao, a center of the once prosperous steel industry in the Basque region of Spain, was attempting in the 1990s to reinvent itself for the tourist and information economy. It thus welcomed the advances of the Guggenheim Foundation, which was pursuing a global expansion of the Guggenheim Museum and searching for a site for a new building. Thomas Krens, the director of the Foundation, felt that globalization offered unprecedented opportunities for museums. The Guggenheim, like any other corporation, would benefit (according to Krens) from developing a "global brand" and opening 'branches" throughout the world. This would allow it to acquire sorely needed new exhibition space (like most museums, the Guggenheim can exhibit only a fraction of its collection at any one time), to increase the cultural influence of its collection, and to create new opportunities for revenue, all while efficiently streamlining its administrative operations.

Because the Guggenheim 'brand" was already synonymous with a futuristic architectural landmark (see figs. 17.35, 17.36), Krens sought a similarly bold statement for the Bilbao location. The architect Frank Gehry (b. 1929) was chosen to design the building; it was completed in 1997. It has already become an unofficial icon of the era's utopian dreams-of fluidity, connectivity, and technological sophistication-as well as of some of its nightmares.

Despite its gigantic size, the Guggenheim Bilbao, like the information world itself, seems constantly to be in motion. Its complex curves suggest ships' hulls, sails, and the shimmer of darting fish (Gehry's signature forms derive from childhood memories of watching carp swimming). The building also suggests weightlessness and flight appropriately so, since its contours were designed with the aid of a computer program originally developed for the aerospace industry. The titanium "scales" that clad the structure provide an infinitely variable response to the site, echoing the gleam of the adjacent river and reflecting color from the sky and surrounding buildings. Titanium, which provides far more resistance to urban pollution than does stone, is so tough that the scales need be only a third of a millimeter thick. The panels are so thin that the surface pillows slightly, even fluttering a little in a strong wind.

Unlike a traditional museum space, Gehry' s building does not pretend to be a neutral space architecturally, nor is it designed for small, obedient objects. It features soaring galleries that can easily accommodate even the most immense, ambitious, and difficult sculptural installation. Yet some critics have charged that the breathtaking spaces of Gehry's building function as mere spectacle, overwhelming the viewer's critical faculties with a kind of empty wonderment. They also argue that these spaces overwhelm the art within them. This, they feel, has destroyed any opportunity for productive tension between art and its architectural frame and has neutralized the critical function of the art that the museum absorbs. Many of the works displayed at the Guggenheim were originally developed as part of the institutional critique movement (see Chapter 18), and were intended to strain at the limits of the spaces they inhabited. Institutional critique has, in this sense, been swallowed whole at the new Guggenheim. As the art critic Hal Foster recently described the diminished critical presence of art in spectacular museums like Gehry' s: "It used to be Ahab against the whale, now it is Jonah in the Whale."20 Debates about the ultimate implications of the Guggenheim are ongoing. Critics argue that the museum has alighted like an alien spaceship in the city of Bilbao, ready to colonize the local culture with the aesthetic standards of New York and other major art world capitals (the museum does not provide exhibition opportunities for Basque artists). This, they feel, suggests that its formal gestures toward integration with its surroundings are ultimately meaningless. And yet there is no question that the Guggenheim has brought prosperity to Bilbao, as it has become an important site of art world pilgrimage. It has brought a major cultural resource to an area of Spain that might not otherwise have been able to develop one, and it has become a point of pride for the local Basque population.

Whatever the final verdict on Gehry's structure at Bilbao from the museological perspective, it is clear that its elastic forms respond to one of the key challenges driving current architectural design; namely, how to adapt an art of monumentality and permanence to a cultural milieu of mobility, portability, and liquidity. Gehry addresses this problem by adopting aeronautical engineering techniques and glistening, quasi-mobile surfaces.

But not all contemporary architecture attempts to adopt the Guggenheim's monumental scale. Indeed, in a globalizing climate with an increasing emphasis on itinerancy, there has also been a resurgence of interest in mobile, transient, and compact architectural forms. Oddly enough, projects like Krzysztof Wodiczko's Homeless Vehicles (see fig. 19.11) of the late 1980s can be understood as important precedents for contemporary architecture. The conditions of homelessness that Wodiczko explored (the confusion of distinctions between public and private space, the imperative of constant relocation, and the need for protection) are becoming increasingly common attributes of domesticity itself. Indeed, artists and architects are exploring portability of all sorts as they search for the limit conditions of domesticity under the pressure of mobility. Andrea Zittel (b. 1965), for example, creates luxurious "Living Units" that unfold from portable crates. Lot-Ek Architects of New York (Ada Talia, b. 1964, and Giuseppe Lignano, b. 1963) design homes made from tanker trucks, cement mixers, and other mobile containers. The standard shipping container-both symbol and agent of today's global economic network- serves as the basic module of many of their architectural designs. Their MDU Mobile Dwelling Unit (fig. 19.23) can be transported as a single container but unfolds into a fully functioning modern home.

Many of the most celebrated contemporary artists working in the United States emigrated from elsewhere, and their work often addresses their experiences of dislocation. Do-Ho Suh was born in Seoul, Korea, in 1962, and moved to New York City in 1997. For him, one of the strangest aspects of the move was the shift in the scale and texture, between Korea and the United States, of the architectural and spatial environment. He found himself grappling with an acute sense of disorientation: "I felt that I was granted a new body when I came to America. I was dropped into a strange, foreign space. I felt like I didn't know how long my arms were or how tall I was. I tried to find ways to relate to myself in this new environment .. .. "21 The memory of this dislocation colors much of his work, which deals with issues of migration, memory, and longing.

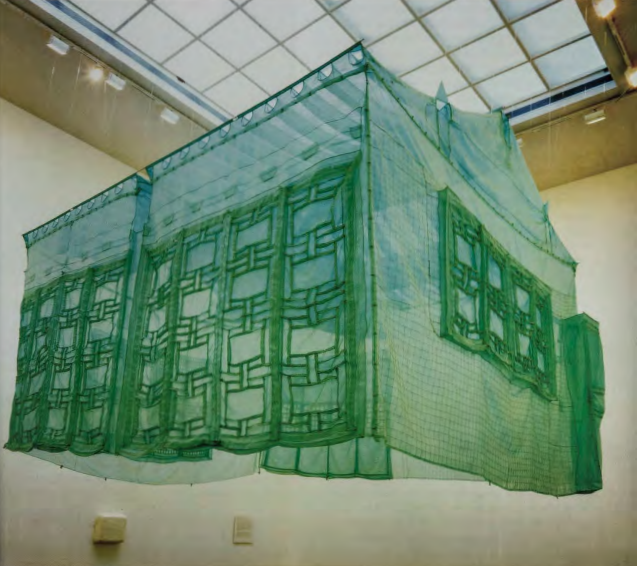

In 1999 Suh returned to the Korean home of his own childhood to produce the work Seoul Home, which is a full-scale, meticulously detailed reproduction in diaphanous green silk of the architectural space of the building. Working in collaboration with master Korean seamstresses, Suh produced a custom-fitted dressing of silk that perfectly reproduced in its sewn seams all of the many architectural details of the original house. Suh's cross of architecture and dressmaking here is not unusual, for as the culture of nomadism develops and architecture searches for more dynamic models of shelter, fashion-which is, in its own way, a portable shell or home for the body-has become a productive metaphor.

When finished, this "dressing" was folded, packed, and taken to the Korean Cultural Center in Los Angeles, where we see it installed (fig. 19.24). The work subsequently traveled throughout the United States and Britain and, as it did, Suh expanded its title to include the names of all the cities in which it had been hosted. As of 2002, its title was no longer Seoul Home, but rather Seoul Home / L.A. Home / New York Home / Baltimore Home / London Home / Seattle Home. The title of the work functions as a record of its public exhibition history. This means that the work internalizes the globalization of the art world itself (major installation pieces like this are now routinely carted around the world to be featured in an ever-expanding network of international biennials). In addition, and perhaps more importantly, the growing list of cities modifies the noun "home" in such a way that it loses its firm association with a single emotional origin and slips paradoxically into an itinerary of displacement. Accordingly, Suh conceives of this "home" as a kind of vehicle for safe passage-"my transportable Korean house has been my parachute," he has written.22 ''.As we all move around from one country to another, from one city to another, and from one space to another, we are always crossing boundaries of all sorts. In this constant passage through spaces, I wonder how much of one's own space one carries along with oneself."23

Cyborgs

In the contemporary mythology of globalization, the elite "new nomads" and the unfolding architectures designed for them move through a series of "nonplaces." As Carol Becker describes them, "Nomads traditionally are pre urban or unurban, but this new breed of nomads is actually posturban, dwelling for a large part in airports-shelters of transport- all over the world, living within a series of temporary nonengagements, ... yet connected to those not present through nomadic objects- cell phones, laptops."24 These posturban nonplaces are often associated with cyberspace, and indeed they share many qualities- featurelessness, timelessness, and homogeneity. This "nonplace" global space has the potential to be liberating, as it allows for unrestricted movement and constant reinvention. But there are other nomads today, far more numerous: the dispossessed, traumatized, or poverty stricken who must move in order to survive or find a tolerable life. This is the globalization of the migrant laborer, the political refugee, the exile, and the literally homeless. For these, the act of crossing is not as seamless as it is for the nomadic elite, and the global space they inhabit, policed by border patrols and distorted by ancient prejudices, is not as exhilarating.

This "other" global space has been explored by the performance artists Roberto Sifuentes (b. 1955) and Guillermo Gómez Peña (b. 1955), whose work traces the persistence of brick-and-mortar politics in global cyberspace. As Gómez Peña writes in his essay "The Virtual Barrio @ The Other Frontier," he was "perplexed by the fact that when referring to 'cyberspace' or 'the net,' [some American artists] spoke of a politically neutral, raceless, genderless, classless, and allegedly egalitarian 'territory' that would provide everyone with unlimited opportunities for participation, interaction and belonging ... . The utopian rhetoric around digital technologies reminded me of a sanitized version of the pioneer and frontier mentalities of the Old West .... "25

Sifuentes and Gómez Peña set out to show that the new frontiers retained many of the qualities of the old, especially regarding the stereotypes surrounding Chicano and Mexican culture. In 1995 they began working on an internet-based performance project (fig. 19.25). At the height of 1990s anxieties over NAFTA and border policy, they opened a website that invited visitors to confess their most deeply held views of Mexican American culture. Finding that the majority of the responses were variations on the theme of an unstoppable invasion from south of the border, the artists decided to call the project the Mexterminator project. They used the stereotypes collected on the site in order to build hybrid cyborg performative personas ("El CyberVato," etc) that would embody the fears and desires of their internet audience. "The composite personae we created were stylized representations of a non-existent, phantasmatic Mexican/ Chicano identity, projections of people's own psychological and cultural monsters- an army of Mexican Frankensteins ready to rebel against their Anglo creators."26

Humor is an important aspect of the Mexterminator project. Hoping "to infect virtual space with Chicano humor," Sifuentes and G6mez-Pefia use the absurdity of their hybrids to ask why they seem funny in the first place.27 Why do people smile at terms the artists invent like "cyber-immigrants," "web-backs," "lowrider laptop," and "Naftaztecs"? The laughter these composite terms and objects elicit is, for the artists, direct proof of the persistence of stereotypes of Latinos as technologically inept. Gómez Peña has noted that even the language of techno culture reveals its lingering attachment to Anglo-American hierarchies. Any phoneme from the Spanish language sounds jarringly foreign in technospeak, and by inserting it there, Sifuentes and Gómez Peña hope to make cyberspace a truly global space- not an anglocentric zone masquerading as an abstract nonplace but a real contact zone, filled with what the artists call "Linguas Polutas" like Spanglish, Franglais, and cyberñol. Eventually, the hope is, Mexicans crossing into cyberspace will not seem funny or threatening-anymore.

Hybrids

As bioengineering becomes a more and more conspicuous feature of the current cultural landscape, artists are becoming interested in examining another aspect of global "crossing" -namely the crossing of genes. Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle is one of many contemporary artists exploring the politics of identity and hybridity in genetic terms. His genetic portraits (p. 622) are large, luminous photographic prints showing side-by-side colored DNA analyses of three individuals. They are presented as group portraits, loosely based on a form of eighteenth-century Spanish colonial group portraiture known as casta painting. Each casta painting featured a three-figure family: two parents of different ethnicities ( carefully labe;ed), and their child (also labeled). The paintings were usually presented in gridded sets so that all possible combinations of racial mixing could be pictured and seen at once. The casta paintings may themselves be understood as concerned with 'bioengineering," inasmuch as they respond to the genetic hybridization that slavery and colonialism brought to New Spain in the eighteenth century. The paintings attempted to codify the uncontrollable process of racial mixing.

Manglano-Ovalle's work updates casta painting by translating it into the conventions of scientific imaging and by emphasizing the destabilization of identity that the previous paintings had already hinted at. The DNA analyses reveal vestiges of individuality- after all, none of the three portraits is the same-but by acknowledging that these individualities are simply effects of differing patterns of the same basic units, the portraits seem to predict the future transcoding, intermingling, and perhaps even homogenization of these separate identities. More disturbingly, they demonstrate that at the deepest levels of the self, supposedly immured and protected from the reaches of globalization and information culture, there are only more codes; codes that can be exchanged and manipulated like any other part of the global economy. Here we see globalization penetrating the most intimate recesses of the body itself, a place that we might otherwise like to imagine to be "off the grid." By drawing our attention to the penetrability of our bodies by the informational matrix, work like Manglano-Ovalle's also entails a radical collapse of the distinctions between interior and exterior space. To quote Mona Hatoum (6. 1952), another contemporary artist working with themes of globalization and exile, "we are closest to our body, and yet it is a foreign territory."28

Eduardo Kac (6. 1962) is a Brazilian-born artist who has been living and teaching in Chicago since 1989. Kac is interested in exploring a new kind of "encounter" and "translation" that is being made possible through bioengineering: the crossing of traditional species barriers. He hopes to introduce subtlety and ambiguity into the highly polarized debates over genetically modified organisms, stem cell research, cloning, and the Human Genome Project. For his GFP Bunny project, Kac collaborated with a French laboratory to produce Alba, a transgenic rabbit (fig. 19.26). Alba's genes have been spliced with a gene from a fluorescent jellyfish, so that when she is illuminated with a certain wavelength of blue light, her entire body glows green. The gene for GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) is routinely used in bioengineering as a marker. But by "commissioning" Alba as an art project, Kac has raised ethical debates about the propriety of bioengineering as an art medium and ultimately about the distinction-if any remains- between the ethics of art and science. By commissioning the rabbit as an artwork, he insists that biotechnological development be examined through an interdisciplinary dialogue.

Kac describes the GFP Bunny project as "a complex social event that starts with the creation of a chimerical animal"29 and follows the ethical controversies that arise from that creation. But his idea is not simply to set off a cascade of ethical debates; he is also determined to remain forever responsible for the socialization of the rabbit, "above all, with a commitment to respect, nurture, and love the life thus created."30 He insists that Alba is a sovereign life form, not a laboratory object, and that the interspecies communication that genetic modification sets in motion must move beyond mere manipulation to become an ongoing conversation.

The same eerie blue light that triggers Alba's transgenic green glow bathes large swags of ancestral corn in the Tuscarora artist Jolene Rickard's Corn Blue Room of 1998-9 (fig. 19.27). Rickard (b. 1956), who was trained in photography and worked in advertising in Manhattan before becoming a full-time artist and scholar, descends from a family of prominent activists who lived ( as she continues to) on the Tuscarora Reservation near Buffalo, New York. Her grandfather founded the Indian Defense League in 1926, and was a tireless advocate for Native rights. This activism fuels her work, which explores issues of Native American cultural sovereignty. Corn Blue Room is comprised of ancestral Iroquois corn which hangs in the center of a space formed by photo stands arranged in the shape of a traditional Iroquois longhouse. The photos there, and in the accompanying CD-Rom projected on the wall, may seem incongruent: corn, a sunflower, a power line, generating stations, and photos of Iroquois political marches. The kaleidoscope of images sets up juxtapositions between manifold forms of power, particularly the industrial power and energy generated by the Niagara Mohawk Power Authority, which in 1957 flooded one-third of Tuscarora land (and which is today one of New York State's biggest polluters), and the caloric energy and cultural power generated by the strains of corn kept and nurtured by generations of Tuscarora women.

The blue light in the installation (which is now widely associated with genetic engineering) confers an aura of technological know-how on the corn, suggesting that the protection of these strains by Tuscarora women is not to be regarded as a merely "natural" or instinctual behavior, but has amounted to a sophisticated form of genetic knowledge and management all along. Indeed, Tuscarora white corn has been carefully bred for size and flavor; its kernels have as much as 50 percent more protein than ordinary corn. At the same time, the blue light seems alien and hostile, and reminds us that these native strains of corn are constantly threatened by the genetic pollution introduced by the genetically modified corn hybrids used widely in American agribusiness. In order to avoid the migration of commercially modified genes into their stock, Native horticulturalists now must time their plantings so that their corn pollinates at a different time from the commercial corn planted nearby. The installation suggests that transgenic encounter is not always beneficial, and that the right to refuse genetic "communication" requires as much knowledge, power, and vigilance as does the impulse to impose it.