18.2: The Figure in Crisis

- Page ID

- 232372

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Although Minimalists ostensibly created objects, what they really created were fields-activated zones of kinesthetic space. And within these fields, objects were no longer objects in the traditional sense. They were understood not as inert, constant, securely bounded packages of matter, but rather as shifting perceptual phenomena that changed constantly in relation to their surroundings and their viewers. Viewers in this expanded field were similarly redefined-from stable Cartesian selves coolly assessing objects in neutral spaces to beings whose self-awareness emerged in a continuous, variable relationship to the spatial and material environment. Expressed in artistic terms, Minimalism helped blur the distinction between "figure" and "ground"-bodies and their environments became entangled in a mutual interplay. The implications of this shift were felt throughout American art in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Bodily Dispersions: Postminimalism, Dance, and Video

One of the primary manifestations of this destabilization of the figure was the rise of a new interest in contingent forms and open-ended processes. This new approach developed simultaneously across many different media not only sculpture but also performance and the new medium of video. Some artists broke down the sculptural object (or sculptural figure) through the dispersion of materials; others the human object (or human figure) by exploring the dispersion in time and space of the viewer's consciousness.

EVA HESSE AND POSTMINIMALISM. Eva Hesse (1936- 70) was among the first to explore the changed condition of objects in the newly charged environmental field of Minimalism. As is evident in Contingent of 1969 (fig. 18.14), Hesse's work had strong ties to Minimalism: like Minimal works, her sculptures derived from serial repetition, simple geometries, and synthetic materials (polyester resin, latex, fiberglass, and plastic tubing in her case). But while Minimal sculpture triggered the viewer's awareness of bodily contingency, Hesse's works carry signs of bodily contingency themselves. Her forms seem marked by time, gravity, and atmosphere: they crack, wrinkle, slump, congeal, yellow, and harden. They seem vaguely human in their organic vulnerability. But their random massing, scattered arrangement, indeterminate contours, and decaying materials suggest not intact, independent figures but rather a kind of invertebrate, primitive, or incontinent corporeality. It is as if the new field of change and contingency opened by Minimalism had begun to act upon the very forms that had triggered it.

Hesse's work is widely understood to have served as the bridge between Minimalism and an entire subgenre called Postminimalism. Searching for a new kind of sculptural form that would be defined by its environment rather than vice versa, Richard Serra (b. 1939) splashed molten lead along the bases of gallery walls; Lynda Benglis (b. 1941) made floor works of pooled and puddled acrylic foam; Robert Morris filled galleries with drooping felt and thread-waste. Many artists saw in work like this the true fulfillment of Minimalism's anti-figural aims. These "sculptures" have no independent formal integrity; they borrow their contours from the spaces they occupy.

At age thirty-four, just as her career was beginning to flourish, Hesse died of brain cancer. While it is tempting to see her scattered, slumping forms as premonitions of her own bodily deterioration, the decay implied in Hesse's work need not be understood as wholly tragic. If in her work we witness the body becoming the field-moving away from its status as "figure" and becoming closer to what we might call "ground"-this is not necessarily a negative process. For the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose writings on bodily perception were to be found on many artists' bookshelves during these years, this field condition approximated our true relationship to the world: we do not move through our environment as self-contained figures in front of neutral backgrounds, but are rather constantly engaged in a perceptual, physical, reciprocal "intertwining" with our surroundings. In Merleau-Ponty's thought, figure and ground, object and context, merge. Robert Morris echoed this sentiment when he suggested that the new sculpture approximated "heterogeneous, randomized distributions that characterize figureless sectors of the world."22

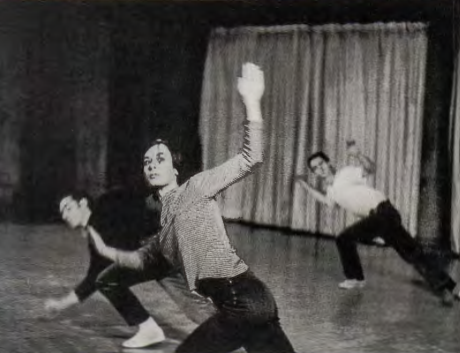

YVONNE RAINER AND A NEW CHOREOGRAPHY. Perhaps the last place that one would expect to find a "figureless sector of the world" would be the world of dance. After all, dance involves bodies (figures) moving in space. But here, too, the 1960s saw an increasing emphasis on the choreographic equivalent of the field condition. In many of Yvonne Rainer's performances, the bombastic tendencies of traditional dance were deemphasized; spins and leaps were replaced by everyday "task-oriented" or "deskilled" movements like walking, eating, or sitting down and standing up. In her work Trio A of 1966 (fig. 18.15), moreover, Rainer destroyed the choreographic equivalent of the figure: the "dance phrase." Dance phrases are a key tool in the traditional choreographic vocabulary, because they allow the dancer to mark the passage of time into a series of coherent, discrete stages, each building to a high point of physical exertion that serves as the main image or "figure" of the dance. Rainer removed such stops and starts and flattened out the hierarchy of movement, so that the dance would appear as a fluid continuum. As art historian Carrie Lambert-Beatty puts it, "the dance becomes difficult to parse visually, like a sentencewithoutspacingbetweenwords."23 The dancer's body is spread out evenly over time in a process akin to the spread of forms over the gallery space in Eva Hesse's work.

VIDEO AND THE NEW-MEDIA BODY. This dispersion of the body in time and space was especially marked in the new medium of video. Video first became widely available to artists at the time of Minimalism's ascendancy, when Sony introduced its relatively affordable "Portapak" camera and recording system in 1965. It was quickly adopted by artists like Nam June Paik (1932-2006), Joan Jonas (b. 1936), Dan Graham (b. 1942), and Bruce Nauman (b. 1941), who, through their associations with Minimalism and performance, were already working with expanded space and durational time. In his installation Live/ Taped Video Corridor of 1970 (fig. 18.16), Nauman took advantage of features peculiar to the video medium, such as its ability to transmit a live image from one place to another, in order to complicate the viewer's existence in time and space. The installation consists of a closed-circuit video system deployed within a long, narrow hallway just 20 inches wide. At the near end of the corridor, above the entrance, is a video camera, and at the far end are two television monitors. One of the monitors shows a live image of the corridor as surveilled by the camera at the entrance; the other shows a taped image of the corridor while empty.

The simplicity of this arrangement belies the mindboggling quality of the experience once the viewer sets it into motion. Upon entering the corridor, the viewer sees herself moving on the live monitor in the distance. The first and natural impulse upon seeing oneself in a television monitor with a live video feed is to treat the monitor like a mirror (which, indeed, it closely resembles in its real-time relay of movement). One tends to move narcissistically toward the monitor, expecting the image to come forward as well. In his installation, Nauman encourages this behavior by placing the monitors far enough away that one needs to proceed down the corridor in hope of seeing one's image clearly. But a viewer entering the corridor finds that as she moves toward the monitor in order to "meet" her image, the image on the screen recedes rather than approaches. Because the camera is behind her, the closer she comes to the monitor, the further she is from the camera, which means that as she approaches the monitor at the end of the hall she sees her own back walking away. Narcissistic satisfaction is thus always tantalizingly out of reach: with each step taken to attain it, it only becomes more elusive. The image on the live monitor forces the viewer to identify with two viewpoints operating at cross-purposes. The other monitor, which shows only a taped image of the empty corridor, proves equally disorienting. Its persistent blankness puts the viewer in the position of a vampire whose reflection in the mirror is always empty. Nauman's corridor makes it difficult for the viewer to hold herself together in the here and now. In doing so, however, it demonstrates the kinesthetic relationship between perception and bodily consciousness in a way that no traditional sculpture could.

While Nauman' s corridor borrowed its drama of bodily awareness (as well as its monitor 'boxes") from the vocabulary of Minimalism, by using video it connected Minimalist space to media space. Thus, along with other video work done at the time, it brought contemporary debates about television and surveillance technology into the purview of the art world. During the 1960s and 1970s, as television attained a definitive hold on American cultural life, well-known media theorists like Marshall McLuhan explored the collapse of distance and the new forms of connectivity that the televisual world would bring. Would this connectivity bring humankind a new and ecstatic form of global awareness? Would the human body transcend its physical limits through media technology (the "extensions of Man," as McLuhan put it) and attain a new, utopian potential? Or would new media usher in a dystopian surveillance state and the destruction of privacy and individuality? Nauman's installation explores these questions without offering an easy solution. The media space in Nauman's corridor-with its delayed, displaced, and self-estranged body- partakes of both the funhouse and the haunted house.

The Subject and the System: Conceptual Art

In the work of Hesse, Rainer, and Nauman, figures lose their integrity and melt into their spatial and perceptual environments. But there are other kinds of environments that also affect the bodies within them: consider the networks of language, information, and economics that structure social and material life. Conceptual art explored the impact of these symbolic systems.

DEFINING CONCEPTUAL ART. Although the meaning of the term "Conceptual Art" is still actively contested among art historians, it generally refers to concept-driven art that flourished on a global scale in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is sometimes defined as art in which ideas take precedence over physical execution. In the late 1960s, for example, Lawrence Weiner wrote a series of terse statements describing the production of hypothetical works, such as Gloss White Lacquer Sprayed for 2 Minutes at Forty Pound Pressure Directly Upon the Floor. As far as Weiner was concerned, a statement like this was the work. The work could either remain in this propositional state indefinitely, or it could be physically performed as instructed. Weiner claimed that this decision was up to the owner.

Because art like Weiner's invested so conspicuously in language, with a physical existence limited to a few dry leaves of documentation, some early commentators claimed that his work, like much Conceptual art, promised a new "dematerialization" of art. But even works that were never physically realized remained stubbornly material as written inscriptions on a surface medium. As writing, these propositions always had some kind of body, and the absence of the described work made the physicality of the inscription all the more precious and conspicuous. Indeed, many Conceptual artists made a point of exploring the visual, physical, and even aesthetic dimensions of seemingly immaterial language. In the late 1960s, John Baldessari (b. 1931) produced a series of paintings featuring snippets of prescriptive prose that he borrowed from art history books. After selecting the passages, he hired a commercial artist to paint the texts onto stretched canvases in standard lettering styles (fig. 18.17). The results, as in What is Painting? of 1968, are humorously paradoxical. The words claim that ''.Art is a creation for the eye and can only be hinted at with words," but the painted words proclaiming this are the art, and themselves appeal to the eye as a pleasing arrangement of lines and shapes.

Given works like these, it is difficult to define Conceptual art simply as "dematerialization." It is ultimately more accurate to say that it exposed the interdependence of ideality and materiality. We will define it here as art that explores the tension between an idea or conceptual system and its embodiment in the real, material world.

CONTRACTUAL PROCEDURES. Like Weiner's statements, works of Conceptual art often consisted of two clearly defined stages: proposition and execution. The artist would first set forth a formula, define a parameter, or simply devise a set of instructions for making a work of art. The plan or idea might then be systematically realized in material form (not necessarily by the artist him- or herself). Sol Le Witt (see fig. 18.13) was influential in articulating this formulaic, contractual procedure. Le Witt, whose work had both minimal and conceptual qualities, insisted that once the parameters of a work had been set, the artist must assiduously obey them. There was no room for improvisation once the process of realization had begun: "The idea becomes a machine that makes the art. If the artist changes his mind midway through the execution of the piece he compromises the result." "The process is mechanical and should not be tampered with. It should run its course."24

The contractual basis of Conceptual art was closely related to the rise of the post-industrial service economy in the 1960s and 1970s. As the American economy began to focus more and more upon the management of information and capital (leaving the actual production of goods to unskilled workers and foreign subcontracts), the relationship between the proposition and the execution of ideas became explicitly political. As art historian Helen Molesworth has argued, Conceptual art production "mimick.[ed] the logic of labor's division into manual and mental realms."25 Conceptual artists were aware of these associations; as LeWitt wrote, the artist "functions merely as a clerk cataloguing the results of his premise."26 Thus, while the Minimalists had borrowed their formal vocabulary from industrial fabrication, the artists associated with Conceptual art tapped into what Benjamin Buchloh has called the "aesthetic of administration." This aesthetic was evident in the appearance of much Conceptual art: typewritten texts, mimeographed diagrams, charts, graphs, reports, and black-and-white documentary photographs presented in gridded formats. And much like a scientific experiment, corporate business plan, or military training exercise, the actual production of the work was a strictly controlled procedure.

INFORMATION AND ITS FAILURES. Conceptual artists used these methodical procedures in order to analyze and critique the administrative powers from which they had been appropriated. In translating directions into action, they highlighted the failures and uncertainties of the process, thus promoting skepticism about the wonders of efficient administration. In Trisha Brown's Roof Piece of 1973 (fig 18.18), for example, fourteen dancers in bright orange uniforms were spread out across a mile-long line of rooftops in lower Manhattan. Brown initiated a sequence of movements, which the next dancer observed and then attempted to replicate, onward through the line of dancers and ultimately returning to Brown herself. But the distance separating the dancers assured that atmospheric "noise" interfered with the accuracy of the "signal," and made this piece a visual equivalent of the game of telephone. By the time the gesture had returned to Brown, it had decayed noticeably from the original. In a decade defined by the rise of information technology (this was the era of the efflorescence of digital computing), Brown's work questioned the accuracy of the transmission and transcription of information. As critic Jack Burnham put it in a 1970 essay about Conceptual art's range of concerns, "Questions of information's predictability, improbability, complexity, message structure, dissemination, delay, and distortion are factors ... for consideration."27

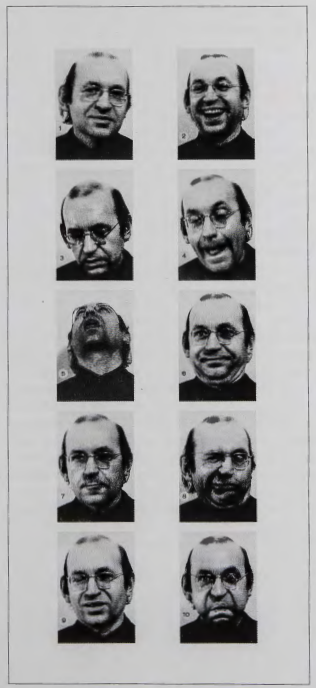

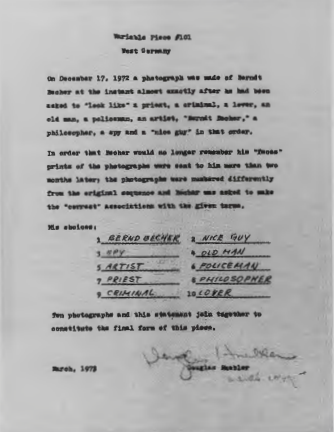

Other artists explored the inadequacy of systems of social classification. For his Variable Piece no. 101 of 1973 (fig. 18.19), Douglas Huebler (1924-97) sat down with a friend (the German photographer Bernd Becher) and read to him the following words: "priest," "criminal," '1over," "old man," "policeman," "artist," "Bernd Becher," "philosopher," "spy," and "nice guy." Becher's job was to adopt a facial expression that would embody each social type while Huebler documented the expressions in photographs. After this initial stage of the project, Huebler waited for two months and then mailed the photographs to Becher, asking him to match the faces he had made with the labels that had originally inspired them. Becher could not put them in the proper order.

Variable Piece is, of course, funny-and not just because Becher' s face has such droll elasticity. Conceptual art frequently reveals, with comic sobriety, the mistranslations, fumbles, and failures of logical and linguistic systems. But this is a critical brand of humor, for Huebler's piece is quite serious about the problem of stereotypes. Huebler demonstrates the inaccuracy-even the cruelty-of the semiotic systems that make society comprehensible. At root, Huebler's work opposes the despotic power of language to promote stereotypical thinking. 'Tm speaking," said Huebler, "against the irresponsibility of language."28

THE ARTIST'S BODY: ELEANOR ANTIN AND CHRIS BURDEN. In Huebler's work, the failure of language to map itself accurately onto the human body exemplified broader concerns with the unstable intersection of subjects and systems in the 1970s. In many Conceptual works, artists used their own bodies to reveal the uncomfortable collision of abstract systems and living, breathing individuals. In these cases, the distinctions between Conceptual art and what is sometimes called Body art become increasingly difficult to draw, and the social criticism becomes more evident. Eleanor Antin's (b. 1935) Carving: A Traditional Sculpture of 1973 (fig. 18.20 ), for example, used a Conceptual vocabulary to deliver a lashing critique of the impact of cultural ideals of feminine beauty. During the summer of 1973, Antin put herself on a strict diet. She documented the diet with one hundred and forty-four 5 x 7 black and white photographs arranged in a grid, showing her progressively thinning body as seen each morning from the front, back, left, and right sides. Carving was based on the tradition of "ideal form" in the history of sculpture. Antin had found a paragraph in a book on carving technique instructing the artist to turn the piece intermittently on its four axes, carving off a bit at a time until the ideal form had been achieved. By following these instructions to document her own weight reduction program; Antin suggests that dieting is an ongoing Conceptual sculpture in which women suffer to achieve artificial idealizations of beauty.

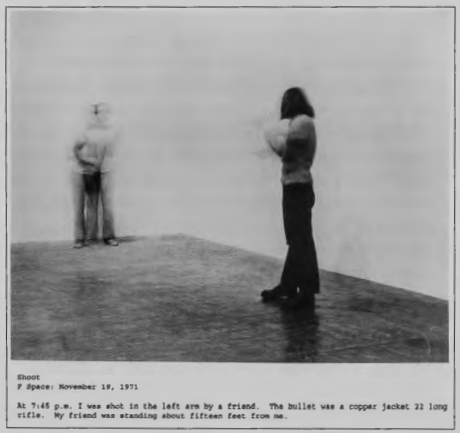

The monkish discipline of Antin's performance was a common aspect of Body art and Conceptual practice, in which artists passively followed their own injunctions, even at the expense of comfort or safety. In its extreme forms this practice shaded into outright masochism, the notorious apex of which was reached on the evening of November 19, 1971, at 7:45 p.m., when the Los Angeles artist Chris Burden (b. 1946), in front of a small invited audience, had a friend shoot him in the arm with a 22 caliber rifle from a distance of 15 feet (fig. 18.21) . The intended result was that the bullet would merely graze Burden's flesh, but some flinch either of Burden's or the marksman's caused the bullet to stray off course. Burden's arm was shot all the way through and he had to be rushed to the hospital.

Burden already had a reputation for placing himself in dangerous or excruciating situations. For his first performance, while still in graduate school, he confined himself in a locker for five consecutive days- a locker just two feet high, two feet long, and three feet deep (Five Day Locker Piece, 1971). He would go on to crucify himself on the hood of a Volkswagen (Transfixed, 1974) and to bring himself, several times, to the verge of electrocution (Doorway to Heaven, 1973, 220, F-Space , 1971). Did these performances stem from some deranged sensationalism? Or were they more meaningful than that?

For Burden, Shoot was the epitome of American art, with deep roots in American folklore and culture. As he put it, "Being shot, at least in America, is as American as apple pie, it's sort of an American tradition almost." "Everybody watches shooting on TV every day. America is the big shoot-out country. About fifty per cent of American folklore is about people getting shot."29 Burden performed Shoot against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, which was by then being presented in horrific detail on the nightly news. Like Warhol's Disaster paintings, Burden's work raised questions about the representation of violence and the possibility of an empathetic response to it.

By staring down the barrel of the gun himself, Burden brought the American culture of violence into the purview of what we might call the conceptual contract. This contract, common to both Body and Conceptual art, places the artist on both sides of the disciplinary divide: the artist functions as the litigator, administrator, executioner-the designer or enforcer of the system-as well as the subject who is subject to its physical and psychological effects. This double role caused considerable anxiety for Burden: "Dealing with it psychologically, I have fear-but once I have set it up, as far as I am concerned, it is inevitable .... Sometimes I can feel myself getting really knotted up about it, and I just have to relax, because I know it is inevitable. The hardest time is when I am deciding whether to do a piece or not, because once I make a decision to do it, then I have decided-that's the real turning point. It's a commitment. That's the crux of it right then."30

In Shoot, because Burden had initiated the procedure that he now found himself enduring, the option of simply aborting the experiment was always available. Thus the absurdity, danger, and arbitrariness of the procedure were highlighted, and the "inevitability" Burden invokes above brought into question. The art historian Frazer Ward draws attention to the role of the audience in Shoot, showing that the work also begged the question of public complicity. By including a small but formal audience in the performance, Burden shifted part of the dilemma of responsibility onto them. Why did no one in the audience stop the shooting? By inviting this question, Burden's work aligns the conceptual contract with the social contract. For if Burden's shooting was not really inevitable, how inevitable are the similarly contractual rules and abstractions (military strategies, the death penalty, etc.) that lead to violent deaths around the world? Burden's meticulous passivity in the face of "inevitable" procedures functioned as a call to action, and forged a concrete connection between the ethics of art and the ethics of obligation.

Figures of Resistance

The crisis of the figure in the 1960s and 1970s was carried out primarily through real bodies-we have traced it, for example, in video works that disperse the viewer's bodily consciousness and in conceptual works that subject the artist's body to mechanistic procedures. But despite the flourish of these direct bodily practices in this period, figurative representation-the depiction of the human form-did not simply disappear. In addition to its persistence in Pop painting, figuration developed in vibrant new directions in the work of artists like Chuck Close (b. 1940), Alice Neel (1900-84), and Philip Pearlstein (b. 1924). And it played a critical role in the work of artists of color, who used it to contend with political problems related to the perception-the representation-of bodies. This activist figuration operated on many levels. Faith Ringgold (b. 1930), in her Black Light series of 1967 (fig. 18.22), developed an entirely new theory of color in painting, in which she rejected the traditional use of white paint to create the effects of light in an image, substituting instead subtle variations of color. In her paintings, the beauty of the black body does not depend upon a color scale in which white signifies light or purity.

T. C. CANNON AND BETYE SAAR: REANIMATED STEREOTYPES. More commonly, artists of color used figurative imagery as "found imagery," which they repurposed in order to dismantle derogatory stereotypes that misrepresented their historical experiences. Native American artists, long laboring under the rubric of the "Vanishing Race," had much to gain by critiquing such stereotypes. But instead of attempting to circumvent or deny the feather-bonneted warriors that had been this country's visual legacy since George Catlin and Edward Curtis, many Indian artists in the 1970s seized these stereotypes and turned them to their own purposes. T. C. Cannon's (1946--78) painting Collector no. 5 or Osage with Van Gogh of 1975 (fig. 18.23) updates Wohaw Between Two Worlds (see fig. 9.37) of a century earlier. Unlike Wohaw, the Indian subject no longer seeks rapprochement between two worlds-he has achieved it. Although he strikes the stereotypical pose of the stoic Indian, Cannon's collector embraces the globe with his eclectic possessions: a Navajo rug, an Indonesian wicker chair, historic Oklahoma Native finery, and Van Gogh's iconic Wheatfields on the wall. Inverting the expected ethnicities of collector and collected, he crosses his leg jauntily, confident in his understanding that Native peoples have long mediated diverse worlds in a cosmopolitan manner (see portrait of Hendrick, fig. 2.22).

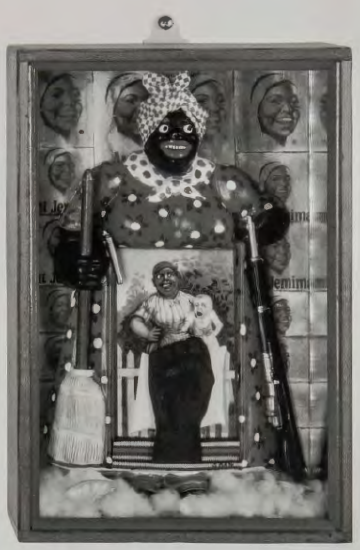

In the 1970s, African American artists also confronted a pervasive culture of stereotype that they were determined to overturn. As in the New Negro movement earlier in the century (see Chapter 15), their overall intent was to replace negative images with positive images, but their approach refrained from the assimilationist tone of New Negro rhetoric. The California artist Betye Saar applied militanthumor to her reworking of the "black mammy" stereotype, used for decades in advertising as a symbol of cheerful and reliable subservience. In her 1972 assemblage The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (fig. 18.24), inspired in part by Joseph Cornell's box assemblages (see fig. 14.34), Saar used a found figurine, a "black mammy" memo-and-pen holder, and recontextualized it in order to reverse its original meanings. She augmented the figure's emblem of servitude, the broom, with a pistol and a shotgun, converting docile servility to angry volatility. In the place of the memo pad, Saar inserted an image of a black nursemaid holding a white baby together with the symbol of the Black Power movement-a clenched fist. The "memo" to be taken here, Saar implies, is that black slaves and servants have taken care of whites long enough. The shallow wooden box is lined with a grid of faces from the Aunt Jemima pancake mix logo and bracketed with mirrors so that the smiling stereotypical faces seem to extend forever. Repeated ad infinitum, the smile becomes sinister, perhaps masking other, more aggressive intentions. Saar's repetition and recontextualization of the 'black mammy" stereotype transform it from a racist device into a new symbol of the black woman as knowing, powerful, and ready to act in her own interests.

MURALS, ON AND OFF THE WALL. A strong community of Chicano figurative artists developed in Los Angeles in the 1970s. Perhaps the most conspicuous- and certainly the largest- example of their work is The Great Wall of Los Angeles. Painted under the direction of Judith Baca along a concrete wall in the San Fernando Valley, the mural stretches over a half mile. The longest mural in the world, it reinterprets the history of Los Angeles from a multiracial perspective, using figurative representation to recover and preserve narratives that might otherwise have been lost (fig. 18.25). The project was· part of a nationwide revival during the 1960s and 1970s of the mural form, which had been made popular by Mexican artists in the 1930s (see Chapter 16). Unlike the murals of the 1930s, however, Chicano murals flourished without institutional endorsement. Like graffiti, these murals tended to be produced "a la brava," which means that they were improvised in the field without elaborate preparatory sketches.

In the early 1970s, the Chicano artists' group Asco (meaning "nausea" in Spanish) devised a form of active figuration that combined Conceptual art and performance with the mural painting tradition. The members of Asco felt that murals had become too comfortably established as the "Chicano" medium, and had succumbed to the inertia of tradition. Moreover, the members (including Harry Gamboa, Jr. (b. 1951), Gronk (b. 1957), Willie Herron (b. 1951), and Patssi Valdez (b. 1951)) felt that in recovering lost histories, murals tended to immobilize them within predictable formats. Asco preferred the uncertainty of a constantly rewritten present. As Gronk put it, "A lot of Latino artists went back in history for imagery because they needed an identity, a starting place ... . We didn't want to go back, we wanted to stay in the present ... and produce a body of work out of our sense of displacement."31

That sense of displacement became evident in Asco's displacement of the mural tradition itself. Asco was (to quote Gamboa) "intent on transforming muralism from a static to a performance medium."32 In 1972, having been rebuffed by a curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for suggesting that Chicano art be included in museum exhibitions, group members spray-painted their names, graffiti style, onto all of the museum entrances. This "mural," according to Gamboa, became "the first Conceptual work of Chicano art to be exhibited at LACMA." In Instant Mural (1974), two members of the group were strapped to the exterior wall of an East Los Angeles liquor store with masking tape. In Walking Mural (fig. 18.26), the group dressed up as characters from typical mural scenes and wandered along a busy street in East Los Angeles. One character's headdress included part of a portable masonite wall-structure, making it clear that this was a mural that had come down from the wall and walked away. For Asco, history was not to be encapsulated in representational form but was to be perpetually reanimated, capable of making direct and unpredictable interventions in contemporary politics.