18.3: American Spaces Revisited

- Page ID

- 232373

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)By the mid-1970s, American art had fulfilled many of Kaprow's 1958 predictions about a "new concrete art." It had shifted decisively toward a direct and multifarious engagement with everyday life, and had become an instrument of social activism and political confrontation. In the process, many layers of aesthetic distance that traditionally separated art from its objects of commentary had been stripped away. As art_ moved to occupy the spaces of everyday life, it altered those spaces irrevocably; this was particularly true of three spheres that have long traditional histories in American culture: the museum, the landscape, and the home.

Challenging the Museum

The most immediate space to be transformed by these newly active arts was the museum itself. Whereas in 1822 Charles Willson Peale had pictured the museum in a natural and seamless relationship to the artist (see The Artist in His Museum, fig. 5.33), artists now had more complex, antagonistic attitudes toward the institutions that controlled the presentation of their work. Minimalism, Pop, Conceptual art, and Performance were the origins of what is now known as institutional critique, a cluster of art practices that aim to reveal the social and political conditions of the art museum (its funding structures, its class, race, and gender biases, etc.) that are neutralized or rendered invisible by traditional practices of display.

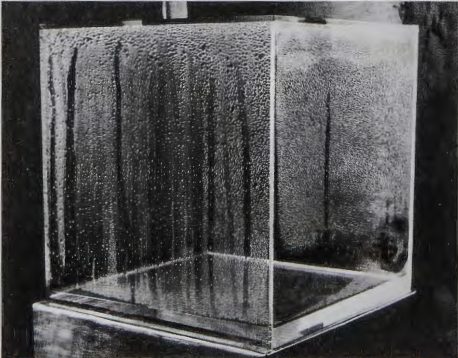

HANS HAACKE AND VITO ACCONCI. An early and influential work of institutional critique was Hans Haacke's (b. 1936) Condensation Cube of 1963-5 (fig. 18.27). Produced at the height of Minimalism's popularity, it elegantly demonstrated that Minimalism's hypersensitivity to its surroundings could lead to a broader awareness of the conditions governing museum display. The piece is disarmingly simple: a quantity of water is sealed inside a plastic cube and set on a pedestal. Gallery spotlights, along with the presence of warm bodies in the room, cause the temperature inside the unventilated cube to rise. The water inside evaporates and condenses along the inner surface of the plastic, changing the appearance of the work. Thus, while Condensation Cube resembles Minimal sculpture, it is closer in spirit to the small instruments in museums ( called hygrometers) that measure humidity. Museums install these instruments to help ensure that atmospheric conditions remain constant in the galleries and do not affect the art. Haacke's cube, on the other hand, is not there to protect art from such "conditions," but rather to internalize and display them. Art, it suggests, is inseparable from the conditions under which it is observed.

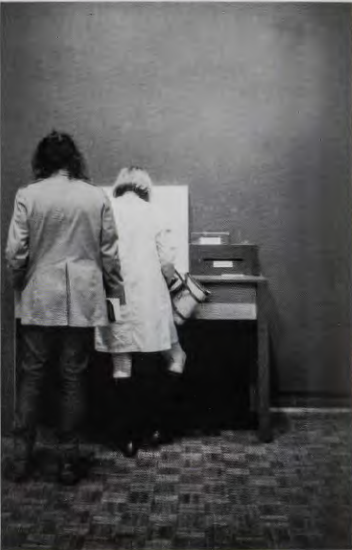

Vito Acconci's (b. 1940) 1970 work Proximity Piece used the strategies of Performance and Conceptual art to demonstrate that the "neutral" conditions of the art museum required careful social maintenance (fig. 18.28). His work, too, was inspired by Minimalism; speaking of Minimal artists, Acconci said that "their work made me think of a room as an art space, rather than just a space that happens to hold art. The notion of being forced to confront that space and the people around the sculpture was exciting to me."33 This confrontation was coded into Acconci's proposition for Proximity Piece: "I wander through the museum and pick out, at random, a visitor to one of the exhibits: I'm standing beside that person, or behind, closer than the accustomed distance-I crowd the person until he / she moves away, or until he / she moves me out of the way." 34 The stereotypical museum experience is one of quiet, solitary contemplation in which the individual viewer communes intimately with art and factors out everyday social life. Acconci's Proximity Piece attacked this truism, forcing other museum goers into the uncomfortable realization that the contemplation of art is not natural or neutral, but is sustained by an elaborate series of social conventions that only become visible when they are breached.

MIERLE LADERMAN UKELES. Conceptual art, by incorporating everyday forms of labor and activity into the work of art, made it possible to imagine a collapse in the traditional distinctions between artistic work and regular work. This contributed to institutional critique because it allowed the museum itself to be seen as a space of everyday labor rather than privileged creation. After having her first child in 1969, sculptor Mierle Laderman Ukeles (b. 1939) found herself torn (like so many women before her) between her work as a mother and her work as an artist. Instead of spending her time doing creative work in the studio, she found herself overwhelmed with the repetitive, seemingly endless tasks of nurturing that an infant requires. She eventually came to realize that it was not so much the activities of feeding, bathing, and changing diapers that bothered her as it was that "there were no words in the culture that gave value for the work I was doing." She realized that her art training had only prepared her for a very particular model of work: creative work that led to breakthroughs, advances, and innovations. "Nothing educated me for how to bring a wholeness to taking care, not only creating life, but maintaining life. The creating, the originating, that's the easy part." But the "implementation ... follow through, hanging in there" had been lacking. "I had no models, none, in my entire education to deal with repetitiveness, continuity."35

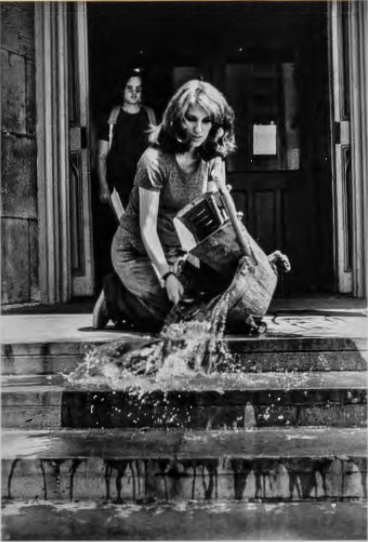

In 1969 she published a "Maintenance Art Manifesto" and began using the tactics of Conceptual and Performance art to promote visibility and appreciation for housework, sanitation, and maintenance tasks that are usually regarded as "outside culture, thus formless and unspeakable." 36 She illuminated these activities "outside culture" by bringing them into the space most fully inside culture (the art museum) and demonstrating how they were normally excluded from view in this context. For Ukeles, art museums maintained their cultural status by functioning as temples of creativity, genius, and originality, which were thereby obligated to stigmatize and marginalize maintenance activities (with their close association with "women's work"). In 1973 she performed a series of planned actions at Hartford's Wadsworth Atheneum that dramatized these priorities. In Hartford Wash, she spent eight hours scrubbing the entry steps and floor of the museum, confronting visitors with the normally invisible labor that was necessary to keep gleaming galleries clean and "neutral" (fig. 18.29).

By revealing the social valencies of exhibition space, artists like Haacke, Acconci, and Ukeles opened the way for subsequent critiques of art-world demographics and representation. For if the apparently neutral gallery space ("The White Cube," as artist and art critic Brian O'Doherty labeled it in 1976) could be revealed as socially charged, so might the objects and artists chosen to fill that field. We will return to these critiques in Chapter 19.

The Mediated Landscape

Like the landscape painters of earlier centuries, late-twentieth-century American landscape artists worked to interpret the interface between nature and culture. Yet by the 1970s this interface was changing rapidly. Although some new landscape art expressed nostalgia for a sublime natural space safe from an increasingly polluted realm of culture, the most influential landscape art in this period sprung from the recognition that nature and culture were inextricable. The global extent of tourism, mapping, mining, and manmade technology suggested that there was no longer any such thing as virgin wilderness. Working directly in the landscape, often at a monumental scale, the new landscape artists encountered nature as an already-mediated sphere rather than a symbol of unsullied purity.

ROBERT SMITHSON. Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty, built in 1970, springs into the Great Salt Lake from a remote point on its northern shoreline (fig. 18.30). The work is monumental in size as well as ambition: built from 6650 tons of rock and mud by a crew of skilled engineers and heavy equipment operators, the spiral is a quarter-mile long. Spiral Jetty was designed to meld with the geology and ecology of its site. Smithson (1938-73), who was interested in crystallography, knew that the lake would eventually deposit a layer of ghostly salt crystals along the margins of the black rock. He knew that the sheltering arms of the spiral would increase the concentration of brine and microorganisms in the salt water, turning the water a deep blood red at the center of the earthwork. He recognized that the Jetty would be subject to the same forces of erosion, alluviation, and disintegration as the rest of the landscape, and would thus function less as outdoor sculpture than as natural formation. All this, along with the profound isolation and stark beauty of the site, makes it tempting to interpret Spiral Jetty as a fully "natural" work of art.

But culture and industry also inform the Jetty. The earthwork lies just a few miles from Promontory Summit, the site of the driving of the Golden Spike that completed the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Smithson was aware of this when he planned Spiral Jetty, and the two monuments (Golden Spike and Spiral Jetty) remain bound in a cross-historical dialogue today. The Jetty's own structure- a roadbed embankment with a path atop it-makes explicit reference to railroad trackbeds. And the Jetty was built with the same heavy machinery and engineering techniques indeed, by some of the same men-as the railroad causeways that were built across the Great Salt Lake in the twentieth century. The earthwork synthesizes industrial processes with natural processes.

By integrating the idea of the railroad in this way, Smithson enters a perennial artistic discourse about the relationship between nature and civilization, landscape and technology. Nineteenth-century imagery tended to place the railroad and the natural world either into a limited state of balance within a narrow "middle landscape" (see Chapter 8), or into strictly oppositional positions. In Asher B. Durand's Progress (see fig. 7.12), for instance, Native Americans, emblems of vanishing nature, resignedly observe the railroad as it conveys the force of "civilization" across the frontier. Spiral Jetty, by contrast, rejects any opposition between nature and industry. In doing so, it also rejects any model of progress measured by the advance of technology over nature; indeed, Spiral Jetty, as it swerves counterclockwise into the lake, suggests a derailment of the linear progress that the transcontinental railroad once embodied. Smithson linked nature and culture in a dialectical synthesis; for him, all landscape was "middle landscape."

Mark Dion

SMITHSON'S MEDIATED STATE of nature remains compelling for artists today. Mark Dion (b. 1961), one of many contemporary artists influenced by Smithson, explores the systems of knowledge that humans devise to comprehend the natural world. Dion has studied both art and biology, traveled in the Central American rainforests, and worked in a conservation laboratory specializing in Hudson River School landscape painting. His installations typically involve the sorting, arrangement, and display of specimens that are ambiguously located between nature and culture. In his Upper West Side Plant Project of 1993, for example, a collection of fruits, vegetables, and plants purchased on Broadway between 110th and mth Streets were dried, preserved, and displayed as if they were strange exotica gathered on a far-flung expedition.

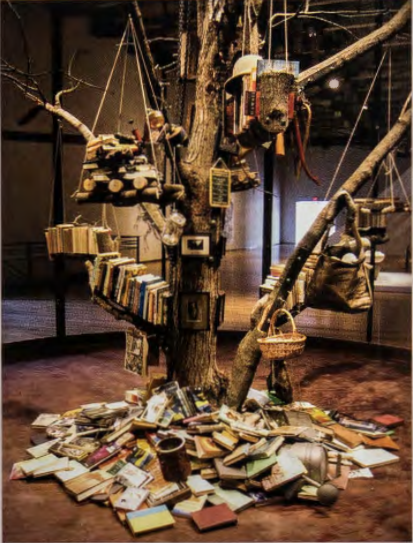

Dion's 2005 installation, Library for the Birds of Massachusetts (fig. 18.31), in a nod to John James Audubon (see p. 170), features a large aviary. Within the aviary is a dead maple tree whose branches, functioning like library shelves, are . filled with ornithology books. Flitting around the tree are twelve live zebra finches. Viewers are invited to enter the aviary and observe the beautiful birds up close. Dion thus creates for his viewers an intimate encounter with real nature (live birds), but everything about the installation calls the directness of that encounter into question. The books are not really "for the birds"; instead they represent the human "tree of knowledge" that structures and determines our understanding of the actual creatures flying around our heads. Dion's point is that just as the birds are trapped in the aviary, we, too, are trapped within a cage of knowledge. We cannot escape it and see these birds in their true unmediated state of reality.

CHRISTO AND JEANNE-CLAUDE. Another important landscape work of the 1970s was Running Fence, designed by the husband-wife team of Christo (b. 1935) and Jeanne-Claude (b. 1935). Over the span of two weeks in the autumn of 1976, this 18-foot-high, 24 and a half mile-long white nylon "fence" meandered through the hilly grasslands north of San Francisco (fig. 18.32). Christo and Jeanne-Claude spent years preparing this transitory work, which, despite its massive scale and complexity, was financed entirely through the sale of preliminary drawings, collages, and early work of the 1950s and 1960s. Catching and conducting the shifting natural light and color, billowing, stiffening, and slackening in the breezes, and following the gentle roll of the hills, this "ribbon of light" was breathtakingly beautiful. But Christo and Jeanne-Claude did not intend Running Fence simply to accentuate the natural sublimity of the area; they also hoped that it would "grab [the] American social structure." 37 In other words, they hoped the Fence would register cultural as well as natural conditions.

In order to realize the project, Christo and Jeanne-Claude required the cooperation of engineers, surveyors, fabricators, politicians, and ordinary citizens. The Fence ran through fifty-nine privately owned ranches and other properties, crossed fourteen roads, and bisected a town. Thus the challenges facing the artists included not only design and construction, but also the securing of building permits, easement agreements, removal bonds, and environmental impact reports-in short, the permission of society. The project was constantly exposed to the possibility of failure. Through seventeen contentious public hearings, the artists had to persuade people unfamiliar with the virtues of contemporary art to support their efforts. A group of local citizens skeptical of the artists' intentions formed "The Committee to Stop the Running Fence" (at hearings, one man repeatedly compared the work to a giant roll of toilet paper). But Christo and Jeanne-Claude considered even their most implacable opponents to be full participants in the project. Every gap and switchback added to avoid the land of an uncooperative rancher, every design compromise made to mollify traffic officers, helped the Fence to reveal the political contours of this particular landscape. And, four years and 3,000,000 dollars after it was conceived, Running Fence was finally built.

The achievement of Running Fence was to manifest a social reality that was not openly acknowledged in earlier American art: namely, that the American landscape is always a ground of passionate opinions, public debate, dissent, conciliation, improvisation, and legal process. In the end the shape of the work follows a political trajectory as much as it does the natural topography, and demonstrates that the western landscape it occupies has as much to do with fences as it does with wide open spaces.

ANA MENDIETA. Fences; administration; territory: these were inevitable catchwords for an art that occupied the real land rather than picturing it from afar. But these words also capture the experiences of many of the immigrants and refugees who encountered the American landscape as part of an unstable new Cold War geography. Ana Mendieta (1948-85) came to the United States in 1961, at the age of twelve. Her parents in Cuba sent her as part of Operation Peter Pan, a controversial effort organized by the CIA and the Roman Catholic Church to evacuate Cuban children who were perceived as vulnerable to Castro's revolutionary government. Although the operation was touted as a rescue, Mendieta remembered it as a wrenching, lonely exile; it was five years before her mother was able to enter the United States to join her. She moved through a series of foster homes and orphanages in Iowa, where she was a frequent target of ethnic slurs.

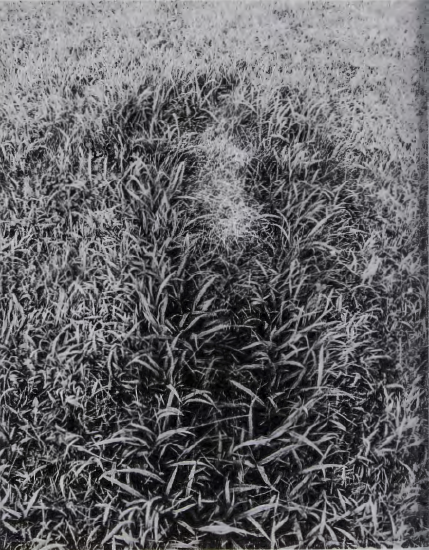

Mendieta studied Performance art, Land Art, and Body art in graduate school, and in 1973 began her series of earth/ body performances called the Silueta series. In these landscape interventions, many of them in Iowa, she used dirt, grass, flowers, etc., to make silhouettes in the scale and shape of her own body ( often pressing her body to the ground to do so), then documented the imprint in photographs and films (fig. 18.33). Mendieta's series embodies the double logic of the silhouette as a form that suggests both presence and absence (see Chapter 6). Mendieta felt acutely that she was in the American landscape but not of it, present in Iowa but always only because she was absent from Cuba. As rendered by Mendieta, the Iowa earth-the heartland of American Regionalism (see fig. 15.5)- becomes a place of alienation.

The forms of the Siluetas recall the ancient fertility "Earth-Mother" that many feminist artists of the period used as a symbol of feminine strength. But Mendieta presents these Venus-like contours as traces rather than presences. She thus celebrates the female figure but protects it from the problematic and dangerous state of objecthood. Throughout the 1970s, Mendieta protested vigorously against the objectification of women's bodies she was one of many feminist artists in America at the time who staged performances that challenged societal indifference to violence against women. Mendieta's dissolution of bodily presence further illustrates the Postminimalist strategy of "figurelessness" as also seen in the work of Hesse, Rainer, and Nauman. Indeed, what better example of the body-becoming-field than a ghostly form merging into an Iowa prairie?

Art and Feminism in the 1970s

AS A STRATEGY designed to overcome the isolation of women, one of the most important feminist tactics of the 1970s was known as "consciousness-raising." It involved bringing groups of women together to share their personal experiences. As they talked, women often realized that the difficulties that they had assumed were personal and particular to them were actually shared by other women. They also learned to consider the ways in which their problems might stem from restrictive cultural norms and social policy rather than personal or biological failings.

An important catchphrase for feminists at this time was "the personal is political." This equation had a galvanizing effect on many women artists of the 1970s, and led them to produce art based on personal experience that would also expose broader political realities. It also laid the groundwork for women artists to explore the causes of gender discrimination in the art world. Linda Nochlin's provocatively titled 1971 essay "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" did just this. Nochli n rejected the argument that women were inherently inferior as artists, and went on to demonstrate in detail the institutional and cultural barriers that prevented women from succeeding. Feminist art programs slowly began to develop in universities, where newly energized artists and scholars began to rescue women artists of the past from historical oblivion and to fight for recognition for contemporary women artists.

Broken Homes

The expanded field of American art after the 1960s embraced not only the vast American landscape but also smaller, more intimate spaces. Myths and traditions surrounding "The American Home" became an especially important field of artistic interrogation. Many of the most influential domestic interventions in the early 1970s were associated with the feminist movement and its reconsideration of traditional assumptions about the home as the realm of women.

The model of American domesticity in the years following World War II was the suburban home, constructed by the tens of thousands and featured as the natural habitat of the nuclear family in countless TV shows and magazines. This wholesale suburbanization of middle-class life combined with the gendered division of labor that characterized the post-war economy: men had careers and mobility; women had children and stayed home.

By the late 1960s, a newly energized feminist movement began to develop the tools to analyze this situation, its causes, and its effects upon American women. Betty Friedan's 1963 bestseller The Feminine Mystique punctured the romanticized myth of the happy, hyperfeminine homemaker, exposing the frustration and despair of women trapped in a "separate sphere" that differed little from the domestic ideal of nineteenth-century American sentimental culture (see Chapter 6).

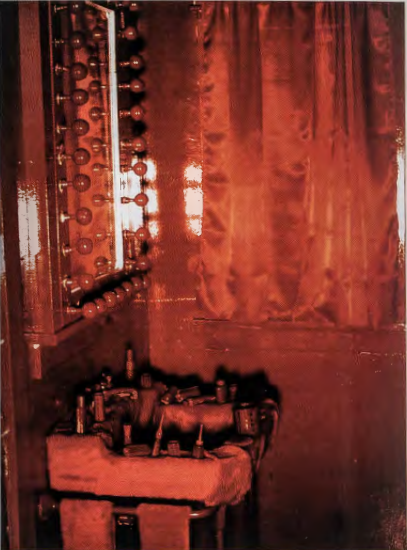

WOMANHOUSE. The Womanhouse project of 1972 was a collaborative performance / installation work that intervened in domestic ideology by physically altering a house. A group of twenty-one students in the pioneering Feminist Art Program, run by Judy Chicago (1939-) and Miriam Schapiro (1923-) at the California Institute of the Arts, transformed a derelict seventeen-room Hollywood mansion into a scathing attack on the "feminine mystique." The house, lent to the group by the City of Los Angeles, had been condemned and scheduled for demolition. In order to prepare it for exhibition, the women had to replace broken windows, install heating and plumbing, rehang doors, replaster walls, and refinish floors (inverting the usual gendering of "domestic labor" as they did so). Once the house was stabilized, each member of the group was responsible for transforming a single room or area.

As they developed their installations, the artists held consciousness-raising meetings in order to tap their memories of childhood homes and their current perceptions of domestic space. Many of the resulting installations used irony and exaggeration to portray the entrapment and loneliness of home life. The kitchen and bathrooms, as highly gendered spaces, were transformed in particularly memorable ways. In Lipstick Bathroom (fig. 18.34), Camille Grey coated the space in a bright lipstick red, as if the room had preserved on its surfaces all of the lipstick applied in front of the mirror over the years. Inevitably recalling blood as well as lipstick, the bathroom equated beauty with horror and highlighted the obsessive quality of makeup rituals and the social insecurities that encourage them. Vicki Hodgetts's Nurturant Kitchen (another monochromatic space-this time in pink) made the biological determinism of the kitchen disturbingly explicit, as multiple fried-egg forms glued to the ceiling morphed into breasts that lined the pink kitchen walls, eventually transforming into plates of prepared food along the counters.

Womanhouse fused art world trends with feminist tactics. The Minimalist use of serial repetition was here deployed to emphasize the numbing repetition of domestic life and labor. Conceptual art's deconstruction of "pure ideas" became a tool for demonstrating the inadequacy of sentimental idealizations of ethereal womanhood. The participatory audience, as awakened by Happenings, was granted a communal space for support and discussion. Womanhouse was open to visitors for the entire month of February 1972, attracting widespread media coverage and some ro,ooo people to see the environment and performances.

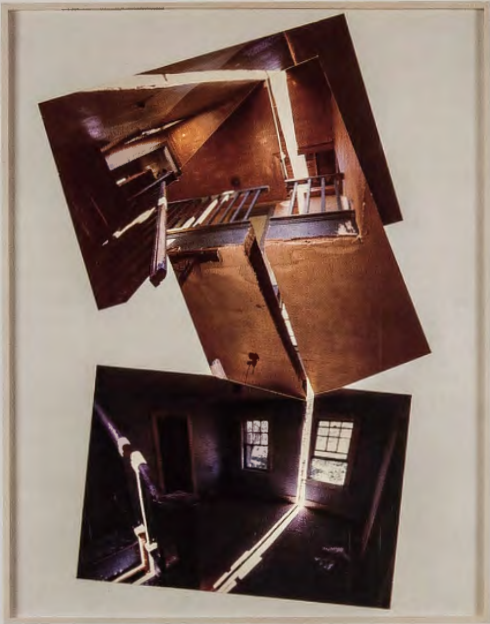

GORDON MATTA-CLARK. Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-78), like the Womanhouse artists, treated architecture as a medium for sculptural alteration. Using everything from chisels to acetylene torches, he made 'building cuts" that altered the perception of architectural space. Following upon the Minimalists' shift from fictive space to real space, Matta-Clark wondered: "Why hang things on the wall when the wall itself is so much more a challenging medium?"38

Matta-Clark's cuts perforated domestic structures, opening new connections between public and private space. The site for his 1974 project Splitting was a condemned suburban house in a blighted area of Englewood, New Jersey (fig. 18.35). With the help of Manfred Hecht, Matta-Clark sliced the house clean down the middle. The idea was simple, but the procedure was extremely difficult. After making the cut (no small task in itself), half of the house had to be held in place with jacks while the foundation below it was cut away. Then the jacks were carefully released and the entire house-half lowered so that the cut would blossom into an open wedge above. This was an exhausting and hazardous endeavor; as Hecht put it, "It was always exciting working with Gordon-there was always a good chance of getting killed."39

Matta-Clark had been trained as an architect at Cornell but soon disavowed the profession; he felt that modern buildings imposed ideology and that architecture was too easily accepted as a limit. In Splitting, he breached that limit. The cut produced a delicate tracery of light that transected the building with "long slivers of liberated space."40 Unexpected spatial relationships between rooms became apprehensible. Thus, even though it literally severed the house, the cut had a connective effect, joining previously separated areas of the house to each other and to the outside world. Matta-Clark wanted to replace the viewer's architectural conditioning with a sense of ambiguity.

For all its beauty, Splitting did not directly address certain of its own preconditions: namely, the planned demolition of the building and the eviction of the African American family that had lived there. In an interview about the project, Matta-Clark noted that "the shadows of the persons who had lived there were still pretty warm,"41 but their fate remains ambiguous. A contradiction embedded in both Womanhouse and Splitting is that their revolutionary reorganization of domestic space depended upon economic upheavals, the condemnation of the host buildings, and the displacement of the former residents. By the 1980s, as artists became more sensitive to such displacements, they began to address domesticity by systematically examining its negation-homelessness- as we shall see in Chapter 19.