18.1: The Space and Objects of Everyday Life- Performance, Pop, and Minimalism

- Page ID

- 172922

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In 1958, the young artist and art historian Allan Kaprow (1927- 2006) published an article titled "The Legacy of Jackson Pollock":

Pollock, as I see him, left us at the point where we must become preoccupied with and even dazzled by the space and objects of our everyday life . .. . Not satisfied with the suggestion through paint of our other senses, we shall utilize the specific substances of sight, sound, movements, people, odors, touch. . . . Not only will [future artists] show us, as if for the first time, the world we have always had about us, but ignored, but they will disclose entirely unheard of happenings and events, found in garbage cans, police files, hotel lobbies, seen in store windows and on the streets, and sensed in dreams and horrible accidents. An odor of crushed strawberries, a letter from a friend or a billboard selling Drano; three taps on the front door, a scratch, a sigh or a voice lecturing endlessly, a blinding staccato flash, a bowler hat-all will become materials for this new concrete art.1

Reading Jackson Pollock's work through the intervening influence of John Cage, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg (see Chapter 17), Kaprow argued that Pollock had broken painting open to a direct encounter with reality, rescuing art from its traditionally secondhand relationship to the world. For Kaprow, the performative quality of Pollock's painting motions, the physicality of his environmentally-sized canvases, and the materiality of his paint hinted at "new concrete art" to come.

Kaprow's analysis turned out to be prophetic, predicting much that would follow in late twentieth-century American art. Kaprow suggested that after Pollock the realm of aesthetics need no longer be populated by discrete "art" objects (paintings, sculptures) or confined to designated "art" spaces (museums, galleries), but might rather extend to "the space and objects of our everyday life." Aesthetic apprehension need no longer be funneled solely through vision (the proper "art" sense) but might also function through smell, touch, hearing, and taste. Art need no longer pretend to exist in a timeless realm, but might flow seamlessly through ordinary time and ordinary events.

Performance

Kaprow was part of a community of artists, dramatists, dancers, choreographers, and musicians in New York in the 1960s who were working to develop new forms of multimedia art and performance. Along with Kaprow and artists closely associated with him, other groups like the Judson Dance Theater and Fluxus (from the Latin for "flow") shared a common focus on chance techniques, ephemeral materials, sensory complexity, and audience participation.

HAPPENINGS. In his own work, Kaprow attempted to bring to fruition the all-enveloping, interactive, multisensory art that Pollock had begun to introduce. He did this at first by developing "environments." In 1958, at the Hansa Gallery in New York, he filled a room with tangles of scotch tape, sheets of plastic, Christmas lights, and skeins of shredded fabric hanging from the ceiling (all accompanied by a pine-scented deodorizer mist). In The Apple Shrine of 1960 (fig. 18.1), he used chicken wire, crumpled newspaper, and dangling straw. Visitors moved through these installations as if they were feeling their way through three-dimensional paintings.

Kaprow went on to expand these quasi-painterly environments into what were eventually called Happenings. Happenings included all of the unpredictable textures and smells of the environments, but added unpredictable events that unfolded in the temporal dimension. These events were initiated by small groups of performers who, working from loose instructions, carried out mundane tasks, made noises or improvised speeches, moved objects around the space, and interacted in various ways with the audience. For audiences, these events evoked surprise, delight, confusion, and even fear. Kaprow described the typical experience of a Happening this way:

Tin cans rattle and you stand up to see or change your seat or answer questions shouted at you by shoeshine boys and old ladies. Long silences when nothing happens, and you're sore because you paid $1.50 contribution, when bang! there you are facing yourself in a mirror jammed at you. Listen. A cough from the alley. You giggle because you're afraid, suffer claustrophobia, talk to someone nonchalantly, but all the time you're there, getting into the act ... 2

Happenings invariably provoked associations with theater. But traditional stage-and-curtain dramatic theater depends upon framing devices that divide the "real" space and time of the audience from the representational space and time of the performance. The stage is separated from the audience by a curtain, proscenium, lighting, and platform, and the beginning and end of the performance are clearly demarcated. These framing devices were abolished in the Happenings along with the separation of art and life that they signified. Happenings were not staged in theaters, but rather (as Kaprow put it), "in old lofts, basements, vacant stores, natural surroundings, and the street, where very small audiences ... are commingled in some way with the event, flowing in and among its parts.''3 Loosely scripted, Happenings were not repeatable or predictable, and it was often difficult to tell when they began or ended.

Happenings, Kaprow wrote in 1961, "are events that, put simply, happen."4 This seems obvious enough. But in uttering this statement Kaprow was alluding to an urgent problem; namely, that authentic everyday experience, the experience of something "simply happening," seemed more and more rare in a culture where every conceivable sensation could be prepackaged by corporate interests, advertising, and the media. In 1961, the historian Daniel Boorstin (1914-2004) wrote his influential book The Image, in which he argued that events in America were being rapidly replaced by "pseudo-events": planned activities like photo ops that might appear spontaneous but are, in fact, staged for public relations purposes. Against this background, Happenings were intended to provide the kind of "spontaneous experience" that was being leached out of American life.

In Happenings this goal of authentic experience, however utopian, more often than not required discomfort. For the duration of Kaprow's A Spring Happening of 1961, for example, spectators were crowded inside a wooden box with only a few peepholes. The Happening was over when the walls of the box collapsed and the people were driven out of the room with a power lawnmower. The sadism here was intentional; in fact, Kaprow had been deeply influenced by the French avant-garde dramatist Antonin Artaud's (1896-1948) notion of the "theater of cruelty," which argued that drastic measures must be taken to break audiences out of their habitually detached and passive absorption of theatrical spectacle. Forced to participate physically in the action, and denied the comforts of impervious spectatorship, the audience had no choice but to embody the encounter of art and life.

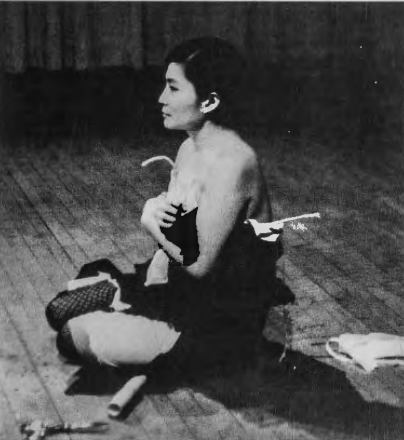

FLUXUS. Yet it was not only the audience whose complacency was shattered by this interactive ethic. Yoko Ono's Cut Piece, performed at Carnegie Hall, New York, in 1965, demonstrates how the artist, too, was now vulnerable (fig. 18.2). Ono (b. 1933) was associated with Fluxus, an international group of artists centered in New York in the mid-1960s. Fluxus "events" shared many qualities with Happenings but tended to be more spare and elegant in their execution. Cut Piece, in fact, consisted of a single directive. Ono knelt on a stage, wearing her best clothing, and set out a large pair of scissors. In a short verbal statement, she invited the audience members to come up one by one and cut away a piece of her clothing. She then remained silent as her audience progressively denuded her.

The artists associated with Kaprow's Happenings were mostly men (sometimes called "The Happenings Boys"), but women, like Ono, Carolee Schneeman (b. 1939 ), Charlotte Moorman (1933-1991), Trisha Brown (b. 1936) (see fig. 18.18), and Yvonne Rainer (b. 1934) (see fig. 18.15) were pivotal figures in performance-based art of the 1960s also. The impact of Cut Piece depends largely upon Ono's gender. As she was progressively stripped of her clothing with a sharp instrument, it was impossible to ignore the connotations of sexual violence. Moreover, as the performance progressed, Ono began to look less like a woman kneeling on stage and more like a "nude"-more like a work of art. Cut Piece thus made the disturbing suggestion that the aestheticization of the female nude in art had some root connection with violence.

As an artist of Japanese ancestry working in post-war America, Ono also brought historical resonances into play with Cut Piece. She had been twelve years old, starving in the Japanese countryside, when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. All her later work was informed by these events. As the art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson has shown, Cut Piece recalled photographs, widely circulated at the time, of bomb victims limping through ruins in tattered garments. In the mid1960s, American society was only beginning to come to terms with the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The participatory aspect of Cut Piece compelled the audience to revisit the nuclear destruction of World War II, but even as it served as a grim reminder, its ritual symbolism also suggested hope through collective gathering and shared witness. Audience members, dispersing, returned home with the scraps of fabric that they had cut, souvenir fragments imbued with a memory of their communal presence at the event. In performance, Cut Piece cut two ways: it activated both the memory of destruction and the imagination of peace.

Pop Art, Consumerism, and Media Culture

The liberatory blurring of art and life that artists like Kaprow and Ono hoped to achieve was not without its complications. Many post-war artists turned to the "everyday" as an antidote to capitalist conformism-as a field of spontaneity, serendipity, and freedom. But others wondered whether the American everyday had not, in fact, already been thoroughly saturated by corporate media. By the early 1960s, the post-war economic boom had progressed to the point where its commercial effects had permeated the everyday landscape with standardized objects, architectures, and media-dizzying arrangements of billboards, subway advertisements, tabloids, comic books, movie posters, and supermarket signs-and the din of televisions and radios. What would happen to the critical function of art if it were to expand so far as to include not only (to quote Kaprow) "the odor of crushed strawberries" but also "a billboard selling Drano"? Would art simply collapse into advertising? Would commodities be reclassified as art?

THE STORE AND THE FACTORY. One of the artists to confront these questions in the early 1960s was Claes Oldenburg (b. 1942), already well known for his Happenings and environments. In December 1961, Oldenburg opened an environment called The Store in an actual storefront on the lower east side of Manhattan (fig. 18.3). Surrounded by blue-collar clothing outlets and humble grocery stores, Oldenburg set up shop. He sold actual-scale versions, made of painted, plaster-soaked muslin, of the banal commodities for sale all around him in the neighborhood: ice cream sandwiches, cigarettes, cheeseburgers with everything. The Store asked uncomfortable questions about the distinctions (if any) between art and commerce. Was The Store a gallery or a retail space? The "goods" for sale alluded to ordinary manufactures and were sold in a storefront among storefronts, but they were also handmade, unique objects. Their price tags evoked both the art auction and the discount store (a man's sock at The Store, for example, cost $199.95).

Oldenburg's productive confusions between high and commercial culture helped stimulate the development of what we now call Pop art, which explored the unstable boundaries between aesthetics and commerce in America. Although The Store itself retained the slapdash look of environments and Happenings, many later Pop artists mixed traditional painting methods with the slick styles and production schemes of commercial imagery. Roy Lichtenstein (1923-97) painstakingly arranged and rebalanced his compositions according to academic dictates, but derived his images from lowbrow advertisements and comic books (fig. 18.4). His paintings featured the small "Benday" dots used in the mechanical reproduction of color in comic books and newspapers, but he painted these dots carefully by hand. Andy Warhol (1928-87) went even further: he appropriated his subject matter directly from product design and mass-media photojournalism, manufactured many of his paintings using commercial silkscreen technology, and worked in a studio he called "The Factory." Many Pop artists, like Oldenburg, also experimented with categorical overlaps between retail and gallery spaces. Galleries sometimes played along: the Bianchini Gallery in New York held a "supermarket" exhibition in 1964, where Pop art was displayed along with real products in an installation complete with aisles and refrigerated display cases.

Pop art like this filled the gallery space, which had long claimed to serve as a refuge from the vulgar commercial world, with the air of the marketplace. The acute cultural discomfort caused by this particular brand of art/ life encounter quickly became evident in Pop's critical reception. Max Kozloff asserted that "the truth is, the art galleries are being invaded by the pin-headed and contemptible style of gum chewers, bobbysoxers, and worse, delinquents."5 Alan Solomon lamented in 1963 that "Instead of rejecting the deplorable and grotesque products of the modern commercial industrial world . . . these new artists have turned with relish and excitement to what those of us who know better regard as the wasteland of television commercials, comic strips, hot dog stands, billboards, junk yards, hamburger joints, used car lots, juke boxes, slot machines and supermarkets."6

THE COMMERCIAL UNCONSCIOUS. The siege mentality that pervaded early criticism of Pop art mirrored widespread concerns-surfacing at precisely this time-about the possibility that the "wasteland of television commercials" had already infiltrated not only the autonomous gallery space but also the last refuge of individual authenticity in America: the psyches of Americans themselves. As the art historian Cecile Whiting has demonstrated, the growth of supermarket-style shopping in the 1950s and 1960s was accompanied by increasingly sophisticated "motivation research" on the part of advertisers. Through motivation research, advertisers hoped to pinpoint, and then exploit, the unconscious desires, fears, and fantasies that drove consumers (imagined almost universally as women) to purchase products. This, in turn, provoked intense concern about the psychological power of advertising. Vance Packard, in his well-known expose The Hidden Persuaders, went so far as to suggest that women floated through supermarkets in a trancelike state, dangerously vulnerable to the seductions of the packaging surrounding them.

The specter of the commercial colonization of the psyche was directly provoked by Pop art. Pop often presented itself as a parodic offshoot of Abstract Expressionism (see Chapter 17), suggesting that the collective unconscious once invoked by action painting had now been replaced by commercial culture. An image like Lichtenstein's Whaam! evokes all of the impact, immediacy, and heroic drama of an Abstract Expressionist painting, but it locates the source of that power in the lowbrow hyperboles of the popular comic book rather than in the roiling, primitive depths of the painter's subconscious. It suggests that the flood of authentic primal force coded in Abstract Expressionism might ultimately be inseparable from the equally formidable power of mass hucksterism: what one critic called the "Mississippi-like flood of information, cajolery, overstatement, and plain bamboozledom from which few Americans are ever free for long."7

Warhol's early painting Dick Tracy, of 1960, is painted in a deliberately fake Abstract Expressionist manner: the drips and gestural paint handling function as coy signs of spontaneity (fig. 18.5). The text in the speech bubble- granted a certain mystic ineffability through selective erasure of letters-resembles the half-formed archetypal symbols in Pollock's early paintings. But if we are to read this scumbled form as having been dredged up from the deepest registers of Warhol's subconscious, what he seems to have found there is not an appealingly preindustrial, Jungian archetype, but rather a vulgar, hackneyed commercial archetype; not Zeus or the She-Wolf but Dick Tracy (compare Pollock's 1943 Guardians of the Secret, fig. 17.4). Warhol proposes here a transfer of the universal archetype from the primordial depths of the collective unconscious to the droll superficiality of the Sunday funnies.

Warhol's painting begs an important question: Is this our true subconscious? Can the common denominator of American life really be found deep in the archetypal collective, or is it in the standardized products and media that all Americans consume? Although Warhol's true feelings on this and other matters were notoriously hard to determine, his work certainly suggested the latter: it is American mass consumption that provides the universal symbols knitting American life together, transcending all distinctions of class or celebrity. As he put it: "what's great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest . . . the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good."8 Unity and community emerge not through shared struggle or dialogue, but rather simply through mass production and consumption. In paintings like Two Hundred Campbell's Soup Cans of 1962 (fig. 18.6), Warhol's repetitive grid and "all-over" composition conveys abundance-an abundance subtly nationalized by its compositional resemblance to the stripes of the American flag. America, the supermarket: an array of commercial sameness in which distinctions and variations are minor and relatively meaningless.

WARHOL'S DISASTER SERIES. Warhol's experiments in a kind of commercial unconscious forced art to recognize its shared territory with marketing and advertising. In some ways, then, Warhol's paintings can be seen to have produced a bracing and transformative encounter with the consumerist reality of post-war American life. But Warhol's work also suggests that the new reality might not be "reality" at all; his paintings explore the possibility that commercial filters have blocked all access to authentic experience. Nowhere is this uncertainty more pronounced than in his Disaster series, produced beginning in 1963 by silkscreening multiple copies of horrific accident photographs onto painted canvases. The image in White Disaster (fig. 18.7) is almost inconceivably terrible: a man, thrown from a mangled, burning car, has been impaled on a nearby telephone pole. In an interview, Warhol evoked the numbing power of mass reproduction, explaining that the repetition of images in the media made them easier to take: "When you see a gruesome picture over and over again, it doesn't really have any effect."9 Yet the Disaster paintings seem determined to test rather than simply to prove this collapse of empathy. Are these images appalling enough to break the modern viewer out of the anesthesia of a packaged and mediated world?

Critics continue to disagree about the ultimate effect of these paintings. For Thomas Crow, the painful reality captured in the images does break through the surface: "the brutal fact of death and suffering cancels the possibility of passive and complacent consumption."10 For Hal Foster, on the other hand, the paintings can only point to an immediacy that has been irrevocably lost. He compares Warhol's repeated disaster images to the pathology of traumatic repetition, in which a person cannot fully absorb the impact of a traumatic event but can only meaninglessly repeat superficial recollections of its occurrence. According to Foster, Warhol's Disaster series, like all of contemporary life, consists only of "missed encounters with the real."11 Whatever one's position on the ultimate meaning of these images, it is clear that Warhol has chosen the most nauseating possible content and subjected it to a test of the limits of empathy in a mediated culture.

In Warhol's use of repetition as a distancing device, we can begin to ascertain a central irony of Pop art: although it helped return avant-garde painting to realism after many years of Abstract Expressionism, it tended to hold its subject matter out of reach, at an immeasurable and impassable distance. Pop art returned painting to the observation of the material world, but the material world had itself become dematerialized-it had become a shallow world of signs, information, and images rather than real things. If Pop art was a form of realism, it was a realism that represented the ways American consumer culture had altered the perception of reality itself.

WAR AND CONSUMPTION: F-111. Pop artists imagined themselves confronting a world in which the scale and compass of consumer capitalism, with its near-total saturation of society, exceeded traditional perceptual structures. The artist James Rosenquist (b. 1933) first felt this while working as a billboard painter in New York in the late 1950s. High above Manhattan, pressed up against a gigantic Hebrew Salami or Man Tan ad, he found himself intrigued by the simultaneously intimate and fragmented vision created by his close proximity to the oversized image. While painting one advertisement, "the face became a strange geography, the nose like a map of Yugoslavia."12 He realized that these intense yet disconnected glimpses of an ungraspable whole were analogous to the consumer's perception of the growing post-war economy, and he took to analyzing this insight in his own paintings.

In April 1965, Rosenquist exhibited F-111 (fig. 18.8) at the Leo Castelli Gallery. Scattered across the surface of the painting are images of various quotidian commodities: lightbulbs, broken eggs, a tire, canned spaghetti. An innocent-looking blond girl under a hair dryer presides over the assortment. But behind her, across the entire horizontal expanse of the painting, lurks an F-111, the new fighterbomber that had just been successfully tested by the Air Force. At 10 by 86 feet, Rosenquist's painting was so large that it wrapped four walls of the small gallery, crowding viewers with the same experience of fragmented proximity that he had experienced as a billboard painter. (This constriction has been relieved in the work's current installation.) F-111 also drew upon the work of the Mexican muralists (see Chapter 16), not only in its scale but also in its intermingling of bodies and machines, its compositional techniques, and its political intent.

For Rosenquist, what was menacing about the F-111 fighter was not only its destructive power, but also the nearly imperceptible way in which the mission of its production had insinuated itself throughout the entire consumer economy. 6703 suppliers located in forty-four states contributed to the design and production of the F-111. Moreover, because huge American corporations like General Electric were also major defense contractors for the project, consumers found themselves indirectly supporting the production of the F-m simply by purchasing items as seemingly innocuous as GE lightbulbs. As Rosenquist's interlocking images implied, the F-111 was inextricable from the general cornucopia of American consumer culture.

Echoing President Eisenhower's recent warnings about the growth of the American "military-industrial complex," Rosenquist claimed in an interview that the American consumer "has already bought these airplanes by paying income taxes or being part of the community and the economy. The present men participate in the world whether it's good or not and they may physically have bought parts of what this image represents many times. "13 When F-111 was exhibited, American combat troops had already entered Vietnam, and the question of whether the war was "good or not" was beginning to be controversial. Of course, Americans had been asked to contribute to many previous war efforts, but they generally did so knowingly. Rosenquist was criticizing a world in which Americans might be unwittingly contributing to a war that they did not support simply by switching on lightbulbs.

F-111 is assembled from fifty-one painted panels, each of which Rosenquist intended to sell separately. Each collector was supposed to take home a single panel, which would then appear as an unintelligible splinter of a larger image. Thus, built into the very structure of Rosenquist's painting was the reminder that every individual act of consumption is part of a bigger picture- a picture that may not be a pretty one. Like Yoko Ono's Cut Piece (see fig. 18.2), which was performed in New York in the same year that F-111 was exhibited, Rosenquist deployed the strategy of dispersion to help individuals recognize their connections to one another in an increasingly intangible social whole. Ironically, the leading Pop collectors Robert and Ethel Scull purchased the entire F-111 ensemble, which now resides intact at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Still, the cracks between the panels remain, hinting at the elusive and illusory nature of the consumer society with which Rosenquist grappled.

Minimalism

The regression of reality that Pop art explored would haunt American art and culture for the rest of the century. Is authentic experience possible in an age of mass consumption? Can reality be directly encountered? In the mid-1960s, a group of artists loosely termed Minimalists (for the spare, laconic objects they produced) took up this question in hopes of answering it in the affirmative. They did so by pursuing the seemingly remedial project of making objects that might be experienced as fully concrete, real entities. In order to create such literal "things," however, they needed to purge sculpture of all its remaining vestiges of representation and illusionism. This was a more difficult prospect than it might seem.

PRECURSORS OF MINIMALISM IN PAINTING. In their attempts to circumvent illusion, Minimalists followed upon painters who had already faced the same challenge. Any mark, however abstract, on a two-dimensional canvas tends to 'bend" the flat surface of the canvas into a suggestion of three-dimensional space, an illusionistic space that does not really exist. Coming upon such a painting, the viewer does not truly confront the painting as a thing in itself, a thing sharing her or his own space, but rather as a "window" into an imaginary representational space. As we have seen in paintings like Flag of 1954-5 (see fig. 17.15), Jasper Johns tried to solve this problem by flattening the flag's pattern and eliminating its background, creating an object (a flag placed bluntly in the viewer's immediate space), rather than a representation ( of a flag framed within some other illusionary space). Frank Stella (b. 1936), working largely in response to Johns, was also trying to break free of the illusionism and spatial slippage endemic to painting. Speaking of painters, he said, "If you pin them down, they always end up asserting that there is something there besides the paint on the canvas. My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there. It really is an object. ... What you see is what you see."14

In his "stripe paintings," like Ophir of 1960-1 (fig. 18.9), Stella attempted to develop a form of visual patterning that would resist slipping into illusionistic depth. The stripes guided the viewer's eye along the surface of the painting, like tracks. Stella painted the stripes in regular, parallel configurations to avoid producing the kind of overlapping planes that the Cubists had used to construct their shallow spatial oscillations. He also used a relatively hard edge, avoiding the misty, spatial atmospherics of color field paintings like those of Mark Rothko (see fig. 17.7). The stripes also followed a "deductive structure," meaning that their arrangement derived from, and drew attention to, the shape and dimension of the actual, physical canvas. Often using industrial metallic paints whose reflective qualities would repel the eye from the surface, Stella applied the paint in a flat, impersonal manner so as to avoid the psychological depth implied by gestural touches. The paint would not represent anything; it would just be itself: "I wanted to get the paint out of the can and onto the canvas. ... I tried to keep the paint as good as it was in the can."15

DONALD JUDD AND CARL ANDRE. Inspired by Stella's example, the artist Donald Judd (1928-94) felt that this kind of literalness would be even more powerful if it could be achieved in sculpture, because it would allow the artist to deploy "the specificity and power of actual materials, actual color and actual space."16 His drastic measures to destroy what he called "fictive space"-so drastic that for many his work ceased to function as art at all-can be seen in his Untitled of 1966 (fig. 18.10). Note, first of all, that Judd's piece sits directly on the floor, without a base. Traditionally, the sculptural base or pedestal is analogous to a frame around a painting; it separates the sculpture from its everyday surroundings. Taken off its pedestal, Judd's artwork shares the floor with its viewer, who must in turn share the floor with the work, and encounter it as an object in his or her own world.

One form of lingering illusionism that Judd and others hoped to eradicate from sculpture was anthropomorphism (the attribution of human form to nonhuman objects). Yet, inherent in our instinct to think symbolically, anthropomorphism is difficult to shake: even a simple standing column triggers an anthropomorphic response. We tend to confer personality upon it, sensing that, like a human being, it harbors an inner life of its own. During the mid-1960s, artists in many different media worked to forestall anthropomorphism and the illusionary "interpersonal" relationships it creates. There was a strong moral component to these efforts: Alain Robbe-Grillet (b. 1922), a French novelist whose work influenced many American artists of this time, felt that things in the world had become "clogged with an anthropomorphic vocabulary," and that it was only by returning objects to their mute, inanimate purview that humans would be able to define the sphere of their own control accurately, confront the world directly, and address social problems responsibly.17

Judd worked to evade anthropomorphism in several ways. First, by using synthetic materials, regularized compositions, and industrial fabrication, he purged his pieces of any traces of organic form. Second, he took measures to deny all interiority to his sculpture. In Untitled, he used shiny industrial materials on some faces of the box in order to emphasize the quality of a hard, repellent surface that cannot be imaginatively penetrated, and used transparent materials like colored Plexiglas on other sides, so that the interior opens as if to prove to viewers that it's only space- just ordinary everyday space-between the structural walls. Inspired by the principle of transparency that had been developed by Soviet Constructivist artists earlier in the century, Judd's piece allows no mystery about its method of construction and hides nothing from its viewer. Its avoidance of compositional complexity imparts a wholeness and reductive simplicity that prevent the viewer from projecting a narrative or personality onto it.

The low profile of Judd's Untitled was a common strategy among Minimalists. Carl Andre's (b. 1935) floor pieces-checkerboard arrangements of metal plates placed directly on the floor (fig 18.11)-were the most extreme examples of this. Not only did they represent the ultimate in horizontality, but their two-dimensional form removed all possibility of interiority. As the critic Rosalind Krauss described it, in Andre's work "internal space is literally being squeezed out of the sculptural object."18 There is a certain brutality about this evisceration of anthropomorphic internal space. Actual space destroys and displaces fictive space.

The Politics of Assemblage

THE MATERIALS OF Minimalism were new: fresh sheets of metal, cleanly cut lumber, and gleaming industrial plastics. But a parallel strand of sculptural production in the 1960s, broadly called Assemblage, favored the use of found objects, scrap metal, and other used materials. Assemblage drew upon a cluster of precedents: Duchamp's readymades, Cubist collages, and Surrealist techniques of juxtaposition. It was also related to current works like Rauschenberg's mixed-media pieces (see fig. 17.17) and the obsolescent props used in Happenings and environments. Assemblage was practiced throughout the United States by such artists as John Chamberlain (b. 1927), Joseph Cornell (1903-1972; see fig. 14.34}, H. C. Westermann (1922-1981), Bruce Conner (b. 1933), and Betye Saar (b. 1926; see fig. 18.24).

Assemblage thrived in a wide range of forms because its diverse materials activated historical and cultural associations that were not so readily conducted in the deadpan syntax of Minimalism. In 1963, for example, the Los Angeles artist Melvin Edwards (b. 1937) began a lifelong series of Lynch Fragments that address the long struggle for African American rights (fig. 18.12). He welded each elegant relief from battered and twisted scrap steel that carries connotations of violence, harm, or force: nails, spikes, chains, hammers, scissors, wrenches, etc. But the delicacy of his assemblies allows these same objects to suggest fortitude and transformation. The chain in Afro Phoenix, no. 1 implies both bondage and bonding; the horseshoe, both restriction and flight (and, with its blatantly vaginal form, fertility and rebirth). Although the Lynch Fragments are abstract, their source materials invite a complex play of cultural associations.

Edwards made Afro Phoenix No. 1 in 1963, the year of the March on Washington and the bombing of the 16th Street church in Birmingham. But given its title's reference to the phoenix (the mythical bird reborn from ashes), the work took on heightened significance two years later, in 1965, when the burning and rioting in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles left thirty-four people dead. This only reinforced Edwards's determination to provide hope and rebirth through his activity as an artist: "My effort in sculpture had to be as intense as injustice, in reverse."19

CRITICAL DEBATES ABOUT MINIMALISM. This rhetoric of aggression, along with the obduracy, blankness, and extreme reductiveness of Minimalist forms, led many critics to interpret Minimal sculpture as nihilistic. To some, the objects' indifference to the viewer seemed smug and sadistic, while to others the artists' denial of transcendent aesthetic experience seemed objectionable. Critics pointed out that Minimalism did not truly evade referentiality as its champions claimed. The industrial idiom and repetitive serial arrangements of the work "referred" to many aspects of contemporary American culture: the repetition of factory production, the technophilia of the military-industrial complex, the banalization of the built environment through urban "superblocks" and suburban "little boxes," and the anonymity of post-industrial finance capital. Indeed, corporations and conglomerates did sense a shared sensibility in Minimalism, and it quickly became part of the decorative lexicon of corporate boardrooms and plazas.

But for others, Minimalism empowered rather than disempowered the viewer by promoting an active, attentive, and expanded model of sculptural spectatorship. Denied the escape of illusionism, viewers were encouraged to appreciate their own existence as real presences in the real space of the gallery. The sculptor Robert Morris (b. 1931) was among the most eloquent proponents of this view. He argued that the underlying logic of Minimal sculpture was not so much reduction as deflection: Minimal sculpture constantly shunted the viewer's attention from the object to its broader context. "The better new work takes relationships out of the work and makes them a function of space, light, and the viewer's field of vision." This, in turn, produces a new awareness of the entire site, including all possible variables of light, positioning, and perspective. For Morris, whose matte gray plywood sculptures were among the most meticulously "minimal" of all, the simplicity of these objects produced a profound environmental and kinesthetic awareness in the viewer. The intimacy, incident, and complexity denied to the objects themselves were returned tenfold to the viewer in the form of an expansive awareness of participatory space. As Morris put it, "it is the viewer who changes the shape constantly by his change in position relative to the work."20

SOL LEWITT AND DAN FLAVIN: THE ROLE OF THE VIEWER. Sol LeWitt's (b. 1928) Open Modular Cube (fig. 18.13) demonstrates the active role of the viewer in the Minimalist installation. Although the sculpture seems so basic as to be simply a diagram of itself-it's just a multi-part cubic lattice-its form becomes endlessly complicated by the viewer's presence. From the shifting perspective of the perambulating viewer, the "arms" of the structure move in and out of alignment, gathering and sustaining the viewer's shifting sightlines as if plotting his or her trajectory in space. The sculpture's simplicity seems to promise the viewer a kind of mathematical purity, but it is impossible to see it from a disembodied position; the form does not remain still because it responds to the viewer's eye. This is true of all sculpture, of course, but the simplicity of Minimal sculpture made such effects of kinesthesia more obvious. As Morris put it, "One is more aware than before that he himself is establishing relationships as he apprehends the object from various positions and under varying conditions of light and spatial context."21

Some Minimalist artists chose to embrace light and space not just as "conditions" but also as artistic media. Beginning in 1963, Dan Flavin (1933-96) used standard fluorescent light fixtures as the primary building blocks of his work. Flavin's Untitled (To the "Innovator" of Wheeling Peachblow) of 1968 (p. 588) straddles the corner of the gallery space. Light from the yellow and pink lamps facing away from the viewer mingles in the corner to create a lovely peach-coral hue. As Flavin's title suggests, a similar color can be found in Wheeling peachblow, a form of late-nineteenth-century glassware that was manufactured in Wheeling, West Virginia. Flavin was an avid collector of peachblow pieces. The difference between his work and its glassware inspiration, however, is that the peachblow color cannot be located anywhere within the physical boundaries of Flavin's fluorescent tubes. Instead it emerges atmospherically and perceptually, by virtue of the mixing and reflection of colored light in the corner (and in the viewer's eye). The "sculpture" is that perceptual space itself.

This activated space was perhaps Minimalism's greatest legacy. Minimalism called for a new level of active participation in the production of meaning; it defined the work of art not as an object but as an encounter between an object, a space, and a viewer or viewers. The "meaning" of a Minimal work was not inherent to the object, but was defined in terms of a field of temporal, spatial, and bodily interaction. The Minimal work did not exist all at once, but rather changed and developed over the entire span of the viewer's attention. This suggested that meaning is constructed in a public space rather than a private one, and helped open art to the social and political field.