15.3: Festivals- Invented Traditions and Ancestral Memories

- Page ID

- 232355

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)During the period from the 1880s to the 1950s Americans in small towns and larger cities originated a rich variety of civic, religious, and historical festivals and pageants. These served many functions, from commemorating significant events in local or regional history to promoting pride of place, with major benefits to commerce and tourism. The "San Jacinto Day Festival" held in San Antonio, for instance, marks Texan independence from Mexico in 1836. German populations in Texas and Missouri originated a variety of "Maifests" and "Oktoberfests" in the later nineteenth century that reinvented seasonal harvest and winemaking celebrations. Suspended during the two world wars because of anti-German feeling, they were resumed and still draw tourists at a time when ethnic ties to Germany are several generations removed.

Such festivals continue into the twenty-first century. Given the deep effect of mass media in shaping our personal and collective identities, along with the spread of a consumer culture that transcends regional and ethnic identities, the role these occasions play in shaping these identities remains an open question. Do they still help renew ties across space and between generations? Or have they become events staged under increasingly artificial conditions, primarily directed at tourism? Both effects are seen, in different degrees.

The Late-Twentieth-century Santero Revival

THE MOST RECENT REVIVAL of the santero tradition dates from the 1980s; according to one account, it has produced more artists than the entire period from 1790 to 1890.14 The current revival, which draws energy from the ethnic identity movements of the 1960s, now includes women, among them Marie Romero Cash, whose La Santisima Trinidad of 1994 (fig. 15.19) revives a nineteenth-century tradition of showing the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Ghost) as three identical figures (see fig. 3.17). Artists such as Romero Cash forge deliberate links with the past, reviving the old ways of making images of the saints. They also embrace innovation, appraising their cultures with the eyes of men and women who have gone away and returned. The disruption of village life resulting from modernization, national markets, new patterns of work, and the growing "Anglo" (or non-Hispanic) presence in New Mexico have brought a new self-awareness among santeros. Studiously exploring a two-hundred-year history has given them an enlarged perspective on their art, as well as a new measure of interpretive freedom. As with Native arts, standards of authenticity, often imposed by outsiders, have conflicted with the artists' desire for innovation. And, as with the Pueblo potters discussed above, the market often insists on a timeless image of their culture. By embracing change and hybridity, however, ethnic artists honor the creative adaptations and cultural mixing that have always characterized encounter in the Southwest.

The proliferation of communal festivals from the 1880s on may be linked to what the historian Eric Hobsbawm has called "the invention of tradition." In a society undergoing transformation from a rural to an urban economic order, with the growing movement of small-town residents to the city, and with the trauma of two world wars, invented traditions were able to provide a connection to a "suitable historic past."15 The invented festivals of the last century reaffirmed the continuities between the generations and assured participants of the persistence of old ways in times of rapid change. They helped Americans make the transition from rural to urban life in a time of geographical and familial uprooting. But the reinvention of tradition also involves reinterpreting the past. To serve the needs of the present, such reinterpretations can result in pronounced topicality, as in the case of the 1947 "Democracy vs. Communism" festival of Aransas Pass, Texas, later renamed the grand "Shrimp-O-Ree," in honor of the community's primary industry. Festivals serve the search for roots in a time of change; they likewise introduce new themes into older forms, balancing tradition with innovation. While noting the continual incorporation of contemporary themes, the historian Beverly Stoeltje nevertheless insists that "if the traditional substance becomes lost, the festival dies."16

"Fiestas Patrias"

Throughout the Southwest, a long history of Hispanic presence and cultural influence is marked by fiestas patrias- ethnic nationalist festivals- which celebrate Hispanic cultural traditions and art forms. Such ethnic festivals rally shared loyalties and maintain historical bonds in the face of pressures to assimilate. Increasingly, with the commodification of ethnic identity, such festivals have played a role in the tourist industry, and are promoted by chambers of commerce. Many of these fiestas patrias are supported by Hispanic business people working "to promote our way of life to the younger generation," in the words of one fiesta organizer.17

HISPANIC ETHNIC FESTIVALS. These festivals take numerous forms. Las Posadas, celebrated in both Arizona and New Mexico, traces its origins to Mexico in 1587, when the Catholic Church used its reenactment of Joseph's and Mary's pilgrimage to Bethlehem, and their search for an inn ("posada"), as a way of attracting Indian converts. The drama was revived in Arizona in 1937 by an Anglo schoolteacher as a means of instilling cultural pride in her Mexican students. It is still performed in Santa Fe during the Christmas season. Also drawing upon the Christ story for popular theater is the Teatro Campesino in San Juan Bautista, California, which produced for television a modern version of the Annunciation to the Shepherds, complete with low riders, migrant farmworkers, and other elements of modern life.

Tejano festivals celebrate the unique Hispanic culture of Texas. Yet like all such invented traditions, they draw on a range of cultural sources and rituals combining Spanish, Aztec, Arab, Jewish, African, German, and Scottish influences, all of which have fed into the modern day cultures of the Southwest.

El Dia de la Raza is celebrated by Hispanic communities on Columbus Day, reinventing Columbus as the father of mestizaje, the mestizo fusion of Hispanic and Native American cultures unique to the New World. An expression both of Hispanic cultural pride and of the new cultural identity emerging from the encounter of European and Native societies, such festivals contributed to the Chicano identity movements of the 1970s.

"DAYS OF THE DEAD." Festival traditions follow the movement of people and cultures across national borders, as communities maintain the traditions of their homelands under new conditions. Mexican festivals such as Cinco de Mayo (the "Fifth of May," honoring a decisive Mexican victory against the French in the 1862 Battle of Puebla) and Los Dias de las Muertos (the Days of the Dead) have acquired new life in El Norte-the country north of the border.

Like other aspects of New World Catholicism, the Days of the Dead festival incorporates elements of preConquest indigenous traditions. The Christian holy days- "Feast of All Saints" (November 1) and "Feast of All Souls" (November 2)-were established in medieval Europe to celebrate the dead who had been observant. The Aztecs of Mexico had two summer festivals that separately honored dead children and dead adults. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, under Spanish Catholic rule, these shifted to late autumn, in order to continue under cover of the Christian holy days. In Mexico it is believed that, on the Days of the Dead, the spirits of the deceased return to this realm. So families hold all-night parties in cemeteries where they offer the pleasures of life, including food, drink, music, flowers, and cigars, to the spirits of their loved ones.

As the festival has migrated across the border, however, the rituals and meanings associated with it have changed subtly. In the Southwest, the Days of the Dead celebrations strengthen kinship ties across generations and national borders, as well as between the living and the dead. Like other more local or regional festivals these celebrations- now seen as a Mexican version of Halloween- bind generations to one another. Related to the Days of the Dead is the "calavera," the laughing or dancing skeleton popularized by the Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada (1852- 1913). Crossing the boundary between the living and the dead, the animated skeleton, whose barbed wit is aimed at those still on earth, has become a familiar figure in the cultural landscape of the Hispanic Southwest. Other practices associated with the Days of the Dead range from the decoration of the grave sites to the creation of ofrendas, domestic altars piled with flowers, candles, and food offerings for the dead (fig. 15.20). More recently, the ofrenda has become a vehicle for exploring issues of Mexican American identity and shared traditions binding those who have crossed the border to those left behind.

Carnival

Many hybrid cultural performances throughout American history have featured a strong African American component. Mostly forgotten today is Pinkster, derived from a Dutch Christian celebration in New Amsterdam, but which in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was an occasion for both slaves and free blacks to come together for revelry, and to crown an ''.African king." An eighteenth century poet wrote of Pinkster, "Every colour revels there, from ebon black to illy fair." More familiar is the Mardi Gras Carnival celebrated in New Orleans, which has become an ever-changing fusion of centuries-old European and sub-Saharan African performance traditions and beliefs.

Celebrated throughout the Catholic world, from Europe to the Caribbean and South America, as well as in New York City, Toronto, and New Orleans, Carnival's origin is in medieval European Christianity, marking the last opportunity for revelry before the devout austerities of Lent. Carnival varies in form from place to place. In the New World, it has especially come to exemplify the transnational links of the African diaspora, an event occasioning vibrant displays of black solidarity and creative outpouring. (Also see Winslow Homer's 1877 painting Dressing for the Carnival, fig. 9.8, showing "Pitchy-patchy," an African American performer in patchwork costume who appeared at various occasions, including Carnival.) New Orleans' carnival hybrid of medieval European and African modes of performance fused in the melting pot of the Caribbean from the seventeenth through the nineteenth century. In the United States, New Orleans was a crucible for the merging of cultures. Around 1800, the city was nearly 50 percent black (both slave and free). Its population included Native Americans, as well as French, Hispanic, and British settlers. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, blacks congregated in "Congo Square" in the French Quarter to dance on Sundays, and it was here that African American contributions to Carnival coalesced.

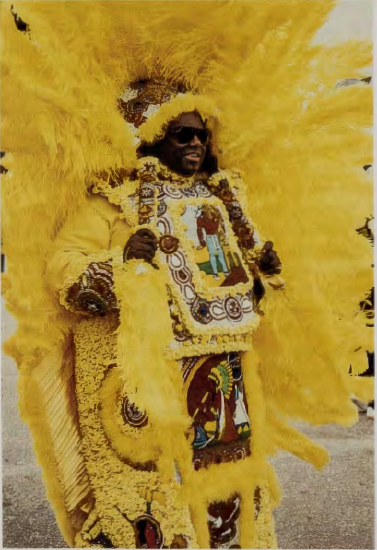

MARDI GRAS "TRIBES." In addition to festival performance mimicking European-style high society (with kings and queens, lords and ladies, and jesters), African American performers added something new in the 1890s: they dressed as American Indian warriors (fig. 15.21). In this lavish fantasy of a Plains Indian costume, the eagle feather headdress is replaced by dyed ostrich feathers, while heavily encrusted panels of sequined beadwork replace the buckskin garments of the Indian warrior. Long hair extensions (again, feathered and sequined) mimic the warrior's braids.

The black Mardi Gras Indian performance troops of New Orleans refer to themselves as "tribes." The making of their sumptuous costumes is a year-long endeavor, requiring a cash outlay of several thousand dollars' worth of ostrich plumes, beads, sequins, and velvet. The "tribe" members are predominantly working-class black men for whom this represents a substantial investment, though some recoup a portion of their expenses by selling the beaded panels of their shirts and dance aprons. Proceeds then go toward inventive new costumes made afresh for the next Mardi Gras season.

Such performers thrive not just in New Orleans, but throughout the Caribbean, in Bermuda, the Dominican Republic, Trinidad, Jamaica, and Cuba.18 The derivation of the black Indians is complex, involving multiple strands of popular culture, religious practice, American and Caribbean history, and a grassroots understanding of the potency of visual symbols for cultural survival. Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show (see fig. 9.42) toured New Orleans in early 1885, just before the Mardi Gras season. The beaded and feathered costumes of the Plains Indian performers in that spectacle surely impressed the African American viewers. Concurrently, in the syncretic Afro-Christian religion of Puerto Rico and Cuba called Espiritismo, some of the "spirit guides" are Native American warrior spirits, whose power derives from their status as aboriginals who resisted European encroachment. Africans in the New World (religious practitioners and festival dancers alike) must have seen in the figure of the American Indian strong parallels to their own oppression. So the American Indian warrior became a symbol of resistance.

Whites were wary of blacks assembling for dancing and performing in ways that might assert their autonomy, so African-style masked performances were sometimes outlawed. The art historian Judith Bettelheim has suggested that while an African American could not masquerade as a powerful African warrior, he could get away with doing so as an American Indian warrior.19 Since white Americans, too, were fascinated with Plains Indians, this was not seen as threatening. In this fashion, a subversive message was carried in an altered medium. To battle with finery rather than weapons, and to adopt the identity of proud warriors of another ethnicity, was one way for African Americans covertly to assert cultural autonomy and resistance in an ostensibly harmless performance.