15.4: The "New Negro" Movement and Versions of a Black Art

- Page ID

- 232356

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)"A people that has produced great art and literature has never been looked upon as distinctly inferior." Charles Johnson20

The 1920s and 1930s saw a renaissance of artistic and literary expression within the black community, known in these years as the "New Negro" movement, and mostly centered in the new black neighborhoods of America's cities. A lively debate emerged over what form the new black art should take. Long defined by distorted stereotypes and racist caricature, black artists sought to gain control over their own representations, and assume authority over their own cultural identity. Yet what was to be the shape of this cultural identity? Should it look to American urban modernity, where most black artists and writers were located? Or should it look to Africa? But were black Americans not also heirs, along with Americans of European descent, to the great visual traditions of Western art and European modernism? These questions percolated through discussions among artists and intellectuals about the nature of a black visual aesthetic.

Modern black identity is a product of momentous and often violent encounters between Europe, Africa, and the New World, originating with the transatlantic slave trade of the sixteenth century. In the wake of the emancipation movements of the nineteenth century, black artists, writers, and performers sought to give voice to their experience as members of American society. Given this complex and painful history of displacement, enslavement, exploitation, and disenfranchisement, the search for roots necessarily pointed in several directions.

The failure of Reconstruction following the Civil War initiated a system of racial apartheid which came to be known as "Jim Crow," in which black citizens were physically and socially segregated and denied basic civil rights in housing, employment, and education. From 1896 on, "separate but equal" (as declared by the Supreme Court decision Plessy vs. Ferguson) was the law of the land. The depth of black oppression was brought home dramatically when black soldiers, having fought for their country in World War I, were victimized in 1919 by a campaign of lynchings and race riots costing so many lives that it came to be known as Red Summer.

Recognizing the unique contribution the arts could make to the process of black self-definition, a broad alliance of writers and artists explored new forms of black self-expression. While much of this investigation occurred in Harlem, in New York City, it was by no means the only center of black intellectual and artistic activity. The nation's largest black community, Harlem promised economic, social, and cultural autonomy for a people who had lived on the fringes of white society throughout their history.

In a 1931 essay, "The American Negro as Artist," Alain Locke (1886-1954) , a noted black intellectual of the "Harlem Renaissance" -a subdivision of the New Negro movement-distinguished three categories of artistic practice: the Africanists or neo-prumtives, the traditionalists, and the modernists. Casting about for myths of their cultural and historical origins, some American black artists (Locke's Africanists or neo-primitives) turned to the ancestral continent for inspiration. Since the breakthrough years of Parisian modernism, African art had enjoyed new stature in the West. Picasso and many others had learned a great deal about abstraction by looking at African carvings in the museums of Paris. American black artists laid special claim to this heritage; their modernism did not have to derive from Europe but could now turn to Africa as the source of a "usable past." Identification with Africa engendered racial pride and a new cultural self-assertiveness. Recent decades have witnessed a greater embrace of the hybrid nature of black modern identity-the product of a European and American black diaspora-and a movement toward what the scholar Richard Powell identifies as "an international art language."21

Other black intellectuals and artists (Locke's traditionalists), struggling to articulate the distinctive features of the black American experience, looked to the African American folk culture of the South forged in the period of slavery and its aftermath. Here the wrenching separation from the culture of Africa became the justification for a cultural expression born of the American experience, including slavery and the "folk" characteristics of the black cultural heritage. Vernacular speech and musical forms migrated north between 1910 and 1930, as the black folk culture of southern slavery shaded into the culture of the black urban working class.

However, for a segment of newly urbanized African Americans (Locke's modernists), ties with a rural, oppressed past rooted in slavery appeared to be a liability, not an asset. Instead, this current of thinking identified black Americans as linked by their experience of forced displacement to the essentially rootless quality of modern life itself. Following the loss of their homelands, and their migration from country to city, the cultural essence of the modernist New Negro was to be found in a new black urban identity.

Underlying these varied prescriptions for a black cultural expression was the issue of the role of black history in the creation of a new modern black identity. Segregation and oppression produced deep social, economic, and polit- . ical suffering, but also gave urgency to the emergence of an assertively black cultural voice. Were the painful historical roots of black identity a burden to be thrown off or were they a necessary condition for self-fulfillment?

Africanist, traditionalist, and modernist approaches most often intermixed in the practice of black artists between the wars. Much of the work of those artists associated with the "New Negro" movement explored, with varying degrees of self-consciousness, the mixed or hybrid nature of black historical experience, as both urban and rural, African and American, modern and "folk." A vibrant expression of this hybrid black identity was jazz, a musical form that fused these varied elements. In Chapter 14, we explored one example of a black modern yet vernacular expression in the work of Archibald Motley. Here, we consider how black artists used traditional materials associated with the rural experience of life in the South.

The Black Artist and the Folk

By the late 1930s, African American artists and performers, from Paul Robeson, in theater, to Jean Toomer and Zora Neal Hurston, in literature, to Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway, in jazz, had all drawn upon southern black dialect and experience in shaping their expressive languages. Adding legitimacy to the artistic uses of such folk elements were oral histories taken from still living ex-slaves; recordings of the music of black chain gangs by Alan Lomax; and the "discovery" of Huddie Ledbetter, a.k.a. "Leadbelly," an ex-convict, performer, and songwriter whose music linked the 'blues" -an urban idiom-to southern rural musical forms. Southern black religion also was seen as a premodern "folk" form that transmuted physical and material hardships into moving spiritual and communal expression.

SARGENT JOHNSON. Black artists between the wars combined a sophisticated modernism with these varied vernacular cultural sources. Sargent Johnson, a California artist, epitomized this hybridity, marked by the multiple currents of twentieth-century history and culture. Based in San Francisco and Berkeley, he drew upon a rich mosaic of West Coast regional cultures: European immigrant, Mexican, Asian-Pacific. From his mentor, the Italian American Benjamin Bufano, Johnson absorbed the compact, monumental, and simplified forms that fused the modernism of Constantin Brancusi (1876--1957) with the influences of Mexican sculpture. From Diego Rivera (see Chapter 16), the Mexican muralist who had executed several Bay Area commissions in 1930, he found support for his own interest in the sober dignity of those who worked the earth-Mexican peasants for Rivera, the descendants of slaves for Johnson.

Johnson's Forever Free (fig. 15.22) grounds black identity in emancipation and the ongoing struggle for freedom that connected the past and future of black Americans. Past and future are apparent as well in the forms he uses. The simplified style of "folk" art had gained new validity in the 1930s, among both black and white intellectuals. Forever Free reveals the growing modernist interest in the work of anonymous regional carvers. Johnson's admiration for West African sculpture, further evident in a series entitled Mask from the late 1920s to the early 1930s, finds expression here in the stylized treatment of facial features and the use of polychrome. The superimposition of the children's figures onto the monumental form of the mother recalls both Brancusi and Mexican sources, while the features of the black mother (modeled on a woman who worked as a maid in Johnson's Berkeley neighborhood) reclaim from racist caricature what Johnson called "the natural beauty and dignity" of his people.22

WILLIAM JOHNSON. Another academically trained cosmopolitan artist, William Johnson (1901- 70) spent a decade in Denmark, returning in 1938 to invent his own folk idiom. He developed a simplified and monumentalized figural language drawing on such European artists as Picasso and Georges Rouault. But he also mined a range of other sources, from children's art (he taught children at the WPA-funded Harlem Community Arts Center in 1939) to African art, to medieval tapestry (encountered through his Danish wife, the textile artist Holche Krake). In place, however, of the earlier emphasis of such artists as Elie Nadelman (see fig. 13.24) on the whimsical and decorative aspects of American folk art, Johnson devised a powerful and original style for painting the southern folk of his South Carolina childhood, their image intensified by his own transatlantic pilgrimage and subsequent homecoming. Like Marsden Hartley, Johnson honed himself as a painter in a variety of different styles, from academic naturalism to a vibrant expressionism. And, like Hartley, he eventually arrived at a self-described "modern primitive" style informed by a sophisticated sense of abstraction.23

Going to Church (fig. 15.23 and p. 484) is a tapestry of saturated color, flat forms, and repeating shapes and stripes. resembling both the collaged cutouts of European modernists and the pieced quilts of southern African American women. Everything seems paired, from the front-seat couple to their two sons in the rear of the wagon, the slender trees and crosses on the hill, and the church and cabin that echo one another on opposite sides of the painting. In graphically simplified narrative, the family unit connects the home to its spiritual counterpart, the church on the hill. As Richard Powell has pointed out, Johnson's primitivism was more than a mirror of European sources. It was a fully internalized expression of his desire to integrate the divisions within black experience-as an artist educated in European traditions yet intent on creating a visual language embodying the memories of his rural African American origins.

Vernacular Black Artists of the Twentieth Century

Members of all ethnic groups make works of art that have life and vitality outside the institutional, studio, and gallery systems. Such works are sometimes lumped together under the rubric of "folk art." Yet it seems prejudicial to call these "folk arts," as if the art of any culture other than mainstream America were operating as nothing more than a tangent to one high culture system. It makes more sense to speak of diverse vernacular traditions, all of which operate independently, yet in an interrelated fashion, and often incorporate aspects of consumer culture into their work, frequently in inventive and humorous ways. Numerous twentieth-century African American vernacular artists have produced works of striking vitality and originality.

HORACE PIPPIN. This self-taught painter (1888-1946) presents a particular challenge to art world standards and stereotypes. His work, along with that of Edmondson and Traylor ( discussed below), was among the first to be celebrated by the New York art world. His paintings were included in an exhibit, "Masters of Popular Painting," held at the Museum of Modern Art in 1938. Pippin's show marked a shift; in the catalogue, the Museum's director, Alfred Barr, wrote that "the purpose of this exhibition is to show, without apology or condescension, the paintings of some of these individuals, not as folk art but as the work of painters of marked talent and consistently distinct personality."24 Lifted out of the category of folk art, Pippin joined the ranks of other major international artists, past and present, celebrated by the Museum of Modern Art for their contributions to aesthetic form.

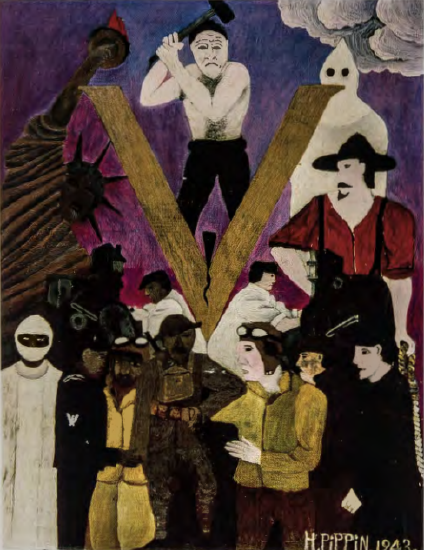

Like some of the early-twentieth-century Native American artists we have examined (see fig. 15.16), Pippin was interested in producing a kind of "insider ethnography" - teaching people about the African American community through his pictures. He once said of himself, "You know why I am great? Because I paint things exactly the way they are. I don't go around making up a whole lot of stuff. I paint it exactly the way it is and exactly the way I see it."25 Pippin was keenly interested in the events of daily life in the African American community around him. He painted scenes of families playing dominoes, saying prayers, eating breakfast. But he also painted portraits of his Amish neighbors, and recreated scenes in the Bible stories that he heard as he grew up. Big themes concerned him as well: events in American history, World Wars I and II, and racism. Pippin had fought in World War I, where he was disabled and shipped home after a year in France; he painted many scenes from his experiences there. In Mr. Prejudice (fig. 15.24), painted during World War II, Pippin provided a trenchant social commentary on racism in America, reminding the viewer that while "V" stood for Victory, and black machinists and steel workers were of vital importance to the war effort at home, the Ku Klux Klan ( on the right) and the Statue of Liberty ( on the left) still vied for control of America. The African American soldiers and sailors, fighting abroad for international freedom even as he painted this work, were still serving in a segregated military.

WILLIAM EDMONDSON. The sculptor William Edmondson (1874-1951) achieved national recognition in 1937 when he became the first African American to have an exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art. This occurred during an era of widespread interest in folk, Native American, and African American art on the part of mainstream art institutions, when academically trained artists were, as we have seen, keenly interested in learning from the expressive works of the self-taught. Edmondson was the son of freed slaves who emigrated from rural Tennessee to Nashville at the end of the nineteenth century. He worked as a laborer in Nashville, doing a stint as a stonemason's helper. When physical ailments caused him to give up a regular job, he turned full-time to carving gravestones and garden ornaments for the local working-class African American community of which he was a part. He carved relatively soft limestone, using a hammer and an old railroad spike as a chisel.

Edmondson' s work extended to biblical themes such as Adam and Eve and Noah's Ark, political and social figures including the First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the popular black boxer Jack Johnson. Humorous vignettes of daily life, such as Po'ch Ladies (fig. 15.25), were important to him, too. In this simple, direct carving of two prim women, side by side, with similar poses, Edmondson captured the essence of a southern neighborhood scene.

Edmondson was "discovered" for the larger art world when an artist who taught at a local college brought the famous fashion photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe (1895-1989) to photograph the imposing-looking sculptor and his works. Dahl-Wolfe's elegant pictures of Edmondson's extraordinary carvings prompted the Museum of Modern Art to organize an exhibition. Though his individual works are now housed in museums and private collections across the country, he intended them for a local audience. Displayed as a haphazard and exuberant group on his own property, under a hand-lettered sign reading "Tombstones for sale. Garden Ornaments. Stone Work. Wm. Edmondson," they became a sculpture gallery of sorts, part of the southern African American tradition of "yard shows" in which diverse media provide a whimsical commentary on all aspects of life, from the spiritual to the political to the aesthetic. Such yard shows continue to be an important feature of the vernacular landscape in the South today, and are not necessarily limited to the black community.

BILL TRAYLOR. Another important vernacular artist, Bill Traylor (1856-1949), was born a slave on the Traylor plantation in Alabama, where he lived and worked most of his life as a field hand and blacksmith, moving to Montgomery in his old age, during the Great Depression. There he made a new life for himself, creating and selling drawings. He slept on the floor of a shoe repair shop, and had a small "workshop" sheltered in an unused doorway on the sidewalk.

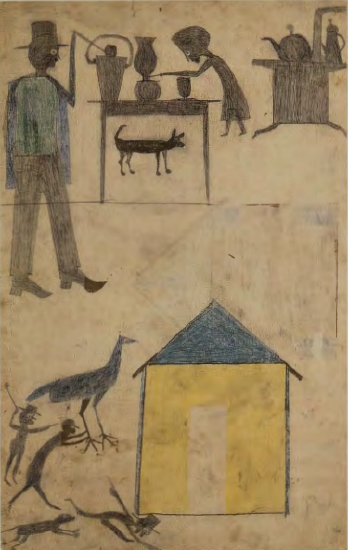

More than a thousand drawings are known from the intensive period from 1939 to 1942 when Traylor worked every day, using pencils, poster paint, and cardboard to make scenes of daily life. Even when given clean artists' posterboard, he would set it aside to "ripen up." He preferred the scuffed and battered surfaces of the cast-off cardboard boxes he was accustomed to. Traylor fashioned his own public art gallery, attaching his work with string to a nearby fence . He sold many of these drawings for a dime or a quarter. In Kitchen Scene (fig. 15.26), he combines dark outline and profile images, above, with a bold yellow house, below. He keenly observed the urban life that passed in front of his little worktable on Monroe Street in Montgomery. But he also drew upon his eight decades of rural life, composing scenes of dogs, farmyard animals, snakes, and birds, with great mastery and a strong sense of line and form. Traylor was known to be a great storyteller, and some of his animals recall the wise beasts of Bre'r Rabbit and other African American folktales.

Charles Shannon (1915-96), a young modernist artist who was fascinated with black culture and music, befriended the elderly artist in 1939, organizing exhibitions for him, and buying many of his works.26 Some thirty years after Traylor died, three dozen of his works were part of an important exhibition, "Black Folk Art in America 1930-1980," at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. The unknown Bill Traylor was deemed "the star of the show" and his works are now among the most sought-after vernacular art.

Lonnie Holley: A Contemporary Vernacular Artist

THE VERNACULAR TRADITION still flourishes in African American neighborhoods across America. In Him and Her Hold the Root (fig. 15.27), the Georgia artist Lonnie Holley (b. 1950) combines two rocking chairs and a gigantic, gnarled tree root. For each viewer, something different comes to mind. To those knowledgeable about African American cultural practices, the composition suggests the potency of roots in medicine and magic, and the power of folk healers and conjurors who have access to a legacy of ancient herbal knowledge. The paired rocking chairs of different sizes (male and female?) suggest the wisdom of the elderly, who may sit and rock quietly on the porch but who carry profound knowledge inside them. Or perhaps Holley is playfully referring to a search for the "roots" of culture-the subject of this chapter. Holley often takes discarded consumer goods (a tabletop copy machine, an electric guitar, a television), conjoins them, and offers them up as trenchant social commentary. The detritus of consumer culture finds new, poetic uses in his humorous and sophisticated work. For more than twenty years, Holley lived near the airport at Birmingham, Alabama, on a property that had long served as an informal dumping ground. He took many of the items discarded there and made his own ingenious built environment, which the city of Birmingham bulldozed in 1995 (after he had achieved international acclaim for his work). Holley commented, "I saw that in the city of Birmingham, where art could be tore down so easy, and trampled upon, it was my responsibility to fight for the rights of the art, I have been to many places. I have understood that our kind of art, the art of black people, have been the first to come and is always the first to go. When our art is too strong, it gets tore down."

JAMES HAMPTON. Many self-taught artists draw, carve, or make constructions because they have a religious message to convey. In some cases, the intensity of their devotion to art-making is the result of a vision or a revelation from God, and they are called "Visionary Artists." In 1950, James Hampton (1909-64), a soft-spoken African American in his forties, rented a garage in a run-down Washington neighborhood to house a project he had toiled at for some time. Over the next fourteen years, until his death, he worked at night, in solitude, after spending all day as a janitor in a government building. Hampton's reclusive life was shaped by three religious experiences he underwent in early adulthood: visions of Moses, the Virgin Mary, and Adam. These apparently were the impetus for his life's work. The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nation's Millennium General Assembly is a multimedia installation (fig. 15.28) comprising more than two hundred individual pieces, including thrones, altars, tables, pulpits, and winged figures. The work is made of cast-off furniture , cardboard tubes, bottles, burned-out light bulbs, and other detritus, all meticulously covered in gold and silver foil scrounged from liquor bottles, cigarette packs, and food wrappings. The Throne of the Third Heaven is rigorously symmetrical, with one side referring to the Old and the other to the New Testament. Hampton's unusual avocation issued from a religious and artistic vision rooted in a strong Baptist faith and a rural African American belief in the power of personal revelation.

Among the many inscriptions on his work, the exhortation "Where there is No Vision The People Perish" may best express Hampton's own feelings about his project. In other inscriptions, he referred to himself as "St. James, Director of Special Projects for the Archives of the State of Eternity." Though his work was not secret-Hampton occasionally showed it to people, and he spoke of wanting to start a ministry in his retirement-it is a reflection of a solitary and eloquent vision.

Some scholars have argued that African American artists such as Hampton, sometimes classified as outsiders or visionaries, fully participate in an African American aesthetic tradition grounded in an African past, and in southern black rural Christian spirituality. Many twentieth century metropolitan artists of color (see Betye Saar, in fig. 18.24) claim these "outsider" works as their aesthetic legacy, alongside the work of modern European masters, a vital heritage to which contemporary artists lay claim in their search for roots. Recent, keen interest in vernacular arts suggests the appeal of something elemental and unspoiled, a vitality not found in work made by people with degrees in studio art and a sophisticated understanding of the art world.