15.2: Preservation, Tradition, and Reinvention in the Twentieth Century

- Page ID

- 232354

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Heritage and tradition are in a constant process of change and renewal, rendering the quest for authenticity, as the critic Lucy Lippard puts 'it, "a false grail."11 Yet Euro-American artists, patrons, and architects throughout the first half of the twentieth century approached preindustrial, Native, and Hispanic cultures with preconceptions about a timeless, unchanging world remote from the pressures of modernization. The "false grail" of authenticity, however, fueled financial support and patronage for regional crafts in crisis. In what follows, we consider the efforts of regional craftspeople themselves to respond creatively to new forms of patronage, both private and federal, preserving existing patterns of use while producing for a market.

Potters, Painters, and Patrons: The Market for Pueblo Arts

Art historians have long recognized the important role of patrons in shaping art traditions around the world, from Chinese emperors to Catholic popes. Yet in the study of Native American art, the issue of patronage can be seen to be more problematic. Because of the economic imbalances between a dominant culture and an indigenous community, the patrons have the power to define authenticity and determine value according to their own criteria, rather than those of the indigenous community. Yet, as we shall see, Native artists have always negotiated between the worlds of commerce and of their own cultural values. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Pueblo arts of painting and pottery-making at the beginning of the twentieth century, when new markets opened up and Pueblo artwork was celebrated far from the small villages where it was created. Two examples, of a male painter and a female potter, illustrate the complexity of the artistic and cultural encounter in the Southwest in the first half of the twentieth century.

PUEBLO WATERCOLORS AND AWA TSIREH. Many Native peoples in the early twentieth century believed that their unique cultural features were destined to die out. It seemed to them that young people, having been educated in white schools, were not interested in the old ways and no longer spoke the language. Some Native people collaborated with anthropologists, to make sure that their cultural artifacts and knowledge were preserved in museums and books. Others looked to art as a form of cultural preservation. In this endeavor, they were encouraged and supported by a small group of white patrons. These patrons (artists themselves, as well as anthropologists and other intellectuals) promoted Pueblo art because they believed that it was through fine arts, as opposed to cheap tourist trinkets, that the culture would survive.

After 1900, Pueblo painters, particularly at Hopi and San Ildefonso, began to experiment with a style of pictorial narrative that had no precedent in their artistic traditions. In many cases the painters were motivated by the same impulse that Plains ledger artists had worked under in the 1880s: to explain their culture through pictorial means, both to themselves and to outsiders. We might use the term "auto-ethnography" for this, for they were narrating their own cultural ways during the same period that anthropologists were writing ethnographic accounts of their cultures. In their art they depicted the unique features of their culture, such as ritual dances and methods of pottery-making. They made small watercolor paintings for sale, sometimes under the sponsorship of local museums, anthropologists, and artists. The Hopi artist Fred Kabotie (1900-80 ), for example, repeatedly painted the Snake Dance, a performance that fascinated outsiders and attracted many tourists. Kabotie and Awa Tsireh (1898-1955) were the most celebrated Native painters of the early twentieth century. Both were prolific and innovative artists.

Awa Tsireh adeptly melded diverse pictorial influences into a coherent style. Born in San Ildefonso in 1898, and given a Spanish name, he later signed his work with his Indian name, which means "Cattail Bird." This was surely a deliberate choice, for many Indian artists recognized that their white audience found Indian names more "authentic." Awa Tsireh came to the attention of the Santa Fe art world in 1917, when Alice Corbin Henderson, a figure in the local literary community, and her husband William Henderson, a painter, befriended the Pueblo painter and began to buy his works. In their home he examined books on modern art, Japanese woodblock prints, Persian miniature painting, and Egyptian art. In 1920, Edgar Lee Hewett, an anthropologist and director of the School of American Research in Santa Fe, commissioned the artist to paint pictures at the school. There, Awa Tsireh worked alongside Kabotie and other Native-born artists.

More than any of his peers, Awa Tsireh successfully merged the symbolic vocabulary of indigenous Pueblo pottery decoration and the eclectic international style of Art Deco and Egyptian Revival. Sometimes he used Egyptian-style outlining of eyes and Art Deco-like abstraction of forms and use of color. In Koshare on Rainbow, done in the late 1920s (fig. 15.16), he depicts the distinctive Pueblo striped clowns who climb poles and engage in buffoonery (see also fig. 2.30 ). Here they straddle a rainbow that emerges from stepped Pueblo cloud forms. Below, two horned serpents create a groundline; out of their tails grows a complex abstract design derived from Pueblo pottery-painting imagery. The colors are the black, white, and rust-red of pottery and ancient mural painting. Native decorative motifs had themselves contributed to the emergence of Art Deco, which in turn became one of several sources that shaped an eclectic style of "Indian" painting. Embedded within a two-way cultural exchange, from colonized to colonizer and back, this art perfectly expressed the situation of Indian peoples in the early twentieth century.

Those who wrote about Native art in the 1920s saw it primarily in romantic terms, as a "pure" expression of indigenous identity, despite the fact that Pueblo people had had four hundred years of continuous contact with non-Indian peoples. The artist and critic Walter Pach, writing in 1920 about contemporary Pueblo watercolors, praised the "amazing pattern ... pure and intense expression" that characterized "the great Primitives"-an art that was "instinctive," and 'American."12 Pueblo watercolor paintings were exhibited for the first time in fine arts contexts (rather than anthropological ones) in Santa Fe in 1919 and in New York City and Chicago in 1920. The first Indian art gallery opened on Madison Avenue in New York City in 1922.

In 1932, the Studio School was established at the Santa Fe Indian School. There, Dorothy Dunn (1903- 91) promulgated an "authentically Indian" way to paint, derived from decorative designs in indigenous arts such as pottery and basketry. But it was actually the generation of Awa Tsireh and his peers that set the standard for Indian painting, which subsequent generations of Indian artists rebelled against when they wished to pursue new forms of experimentation and self-expression.

MARIA MARTINEZ AND THE MARKETING OF PUEBLO POTTERY. New to Indian art in the early twentieth century were concerns about audience and creative individuality. The most famous Native artist of the first half of the century, Maria Martinez ( c. 1880-1980) of San Ildefonso Pueblo, was one of the first potters to sign her work. Biographies and films were devoted to her artistic career, and literally thousands of photographs captured her at work. At a time when the question of how to incorporate Native people into the cultural fabric of America was a vexing issue, she became, in the American imagination, the ideal Indian success story: a woman who integrated the traditional and the modern, the domestic and the cosmopolitan, negotiating the worlds of white patrons and Indian artists, and bringing wealth to her community while embodying the virtues of modesty and industry.

Recognized as an exemplary craftswoman even in her youth, Maria first came to public attention when she and her husband Julian Martinez (1885-1943) spent their honeymoon demonstrating pottery-making at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. They worked on archaeological excavations in Frijoles Canyon in 1908 and 1909. Asked by Edgar Lee Hewett, director of the excavations, to make pots in the style of the unusual black pottery shards that they were finding at the site, she and Julian experimented with firing, and eventually painting, blackware. While black pottery had been made up to the present at the nearby pueblo of Santa Clara, Maria Martinez refined the form with thinner walls, patiently burnishing the surface for hours with polishing stones. When the pottery was fired, this resulted in a lustrous black finish. Julian (who, like Awa Tsireh, was a painter) devised a matte paint technique that resulted, after firing, in an elegantly understated black matt design against a shiny black field. The end product appealed to sophisticated metropolitan tastes (fig. 15.17). By 1920, the pots of Maria Martinez, which she now signed, brought top dollar on an international market. However, by calling attention to her individuality, her signature and her financial success led to strife within the small community of San Ildefonso.

Maria came up with an ingenious solution to squelch potential resentments: signing other people's pots, as well as burnishing pots made by other women and then distributing them to other artists (mostly family members) to paint. The fine, large jar illustrated here is a good example. Signed "Maria and Julian Martinez," the vessel itself was apparently shaped by Serafina Tafoya of Santa Clara Pueblo, polished by Maria's sister Clara Montoya, and painted by Julian Martinez. In these transactions, Maria's role appears to have been entrepreneurial. Was this a form of misrepresentation? In many ways, it constituted an ideal model of Pueblo cooperation, in which each person in the transaction is satisfied. The white patron has the pot with its authenticating signatures. The Pueblo participants, on the other hand, successfully adapted the demands of the market to the needs of the community, devising a way of sharing both work and profits.

Both painting and pottery-making brought wealth into small Native communities such as San Ildefonso. In the 1920s, painters could earn about $900 a year; the best potters made more than twice that-an excellent salary then. The wealth Maria and Julian accrued from the marketing of pottery allowed them to live in a way enjoyed by few Indian people at the time. They hired others to do their farming and household chores, and they owned the first car at San Ildefonso Pueblo. Julian painted this black Ford with his characteristic matte designs, which must have been an impressive sight. Unfortunately photographs were not circulated of these two successful artistic entrepreneurs and their innovative vehicle; instead, the public saw only an image of Maria locked in a timeless world of tradition and authenticity.

The Reinvention of Tradition: Twentieth-century Santero Art

"Tradition liberates creativity, it doesn't stifle it."13

By the 1920s, in the face of poverty and cheap standardized goods, Hispanic village art production had fallen off drastically. Efforts to document, preserve, and develop new markets for traditional artistic and religious expression eventually came from the very culture whose dominance had done so much to undermine these arts. White artists, writers, and collectors embraced the Native and Hispanic arts of the Southwest as refreshingly na"ive and untainted by modernity, prompting collecting and preservation efforts on behalf of endangered arts. The Spanish Colonial Arts Society (SCAS, established 1925) linked Hispanic artists to wealthy patrons, and initiated the production of folk arts for a new audience. Such initiatives paralleled related private efforts to preserve and nurture Native American arts through the New Mexico Association on Indian Affairs ( established 1923; later the Southwestern Association on Indian Affairs), which sponsored an annual Indian Market and administered an Indian Arts Fund.

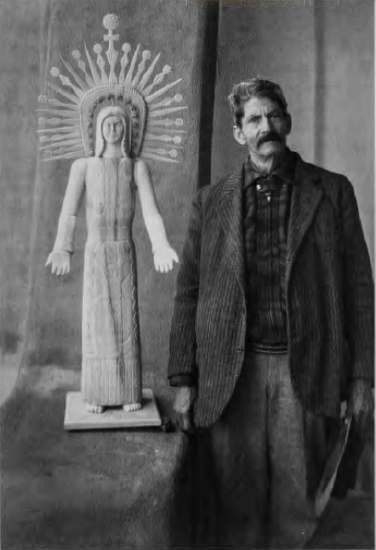

The santero work preserved by the Spanish Colonial Arts Society furnished a vital source of inspiration and support for later generations of santeros. Working in the 1930s, the woodcarver Jose Dolores Lopez (1868-1937), whose powerful hieratic style recalled ancient Mexican stone sculpture, influenced local carving down to the present (fig. 15.18). Lopez's inventive use of indigenous Mexican sources indicates the increasingly international influence on "folk" traditions in the twentieth century, as well as the permeability of the boundary between Mexico and the United States.

Extending the private patronage of the SCAS were the federal programs of the New Deal, discussed in the next chapter. Patrocinio Barela (1900-64), another Hispanic carver who helped reinvent older santero traditions, was supported and exhibited by the Federal Art Project, and was hailed by Time magazine as the "discovery of the year." Barela, like other nonacademic artists in these years, was called a "true primitive" and "a na·ive genius"; his work was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 1936, in an exhibition entitled "New Horizons in American Art."

Choosing to keep alive the devotional power of their images within a rapidly changing world, santeros, from the early-twentieth-century revival of the art into the present, have created works for family and village use, but also for sale to museums and private buyers. Spiritual and communal functions of the saint figures go hand in hand with aesthetic and commercial interests: Working for a wider market, however, gives them the economic independence with which to master a demanding craft.