15.1: The Rediscovery of America

- Page ID

- 232353

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Malcolm Cowley's classic memoir Exile's Return (1933/ 1951) outlines the stages in American artists' and writers' changing relationship to European modernism and to their own native culture. First came a full-blown romance with European culture and a disenchantment with American life that naturally led to expatriation or "exile" to Europe, to a turning away from one's own national culture as the source of one's art. Yet expatriation produced a new perspective on American culture, which expatriates came to "admire .. . from a distance."1 The next stage was repatriation, a return of the exile induced by the realization that, as Charles Demuth put it after returning from Paris in 1921, "It [life in Europe] was all very wonderful,-but, I must work here."2 America looked different after one had been abroad. Its traditions and history helped ground the returning exiles, who felt a new commitment to their native land, and to those aspects of America's cultural inheritance that marked its difference from Europe. That final stage was a "rediscovery of America."

This rediscovery took a range of different forms, drawing on modernist formal concerns coupled with homegrown subject matter, but also employing older narrative, figural, and iconographic elements. Vernacular culture offered forms and subject matter that spoke to the widely felt hunger for premodern life. Answering this hunger were regional promoters who seized on the picturesque elements of the past of various regions to forge an appealing alternative to the commercial present.

The Usable Past

THE TERM "usable past" originated in a 1918 essay by Van Wyck Brooks3 championing the importance of a living tradition of literature to which modern writers could connect. To Brooks, the absence of historical links to the past seemed to impoverish American letters. Key to the notion of the usable past was the creative reinterpretation of historical sources, whereby each generation might create its own relationship to history, in a manner that would serve its particular needs. Every new generation defines what is most useful and admirable about the past for the present moment. The usable past made history a source of renewal rather than a burden. "The past," wrote the cultural critic Lewis Mumford in 1925, "is a state to conserve, ... a reservoir from which we can replenish our own emptiness ... the abiding heritage in a community's life." It was, Mumford continued, the repository of enduring values and qualities that assisted each generation to navigate its challenging encounter with modernity.4

Forging Continuities with the Nineteenth century Craft Tradition

The first years of Americans' encounters with European modernism were characterized by a studied apprenticeship to newer styles, occasionally bordering on slavish imitation. Such a situation brought feelings of cultural inadequacy. Many critics and artists argued that what made American culture distinct was its vernacular, folk, and commercial productions (see Chapter 6). Robert Coady (1876-1921), New York gallery owner and artist, complained in 1917'. "Our art is, as yet, outside of our art world." He then enumerated the subject matter available to American artists, once they put aside their high art prejudices: "The Panama Canal, the Sky-Scraper and Colonial Architecture ... Indian Beadwork, . . . Decorations, Music and Dances . . . The Crazy Quilt and the Rag-mat ... The Cigar-Store Indians .. . The Factories and Mills . . . Grain Elevators, Trench Excavators, Blast Furnaces-This is American Art."5 Coady's list anticipated the subject matter that American artists would seize upon in the ensuing decades, as they struggled to reconcile the formal innovations of modernism with native materials. For American modernists such as Coady and the poet William Carlos Williams, the artist made contact with the soil of place-the physical and historical environment unique to America-and in doing so created a "homegrown" modernism. In the years after World War I, artists on both sides of the Atlantic sought out rural havens where they could live and work cheaply while communing with what they believed to be the authentic character of preindustrial regional cultures more authentic than the urban, at any rate. For many, the retreat to the great continent that lay beyond the nation's cities was also a revolt against a standardized, spiritually impoverished modernity. Paul Strand, in a letter to Stieglitz, complained of the "deadness and cheapness, standardized mediocrity" that he feared would flow outward from New York to corrupt the hinterlands. "I am sure the Americans have already introduced Coney island into heaven .... " Marsden Hartley-one of Cowley's cosmopolitans caught between Europe and the United States announced "the return of the native" to his origins in the rugged landscape of Maine in the late 1920s (see fig. 13.19). Charles Sheeler (1883-1965) felt a similar impulse: "It seems to be a persistent necessity for me to feel a sense of derivation from the country in which I live and work."6 Numbed by the tawdriness of mass-produced objects, these and other artists in the decades between the wars turned back to place, producing a striking body of work in which modernist formal strategies are coupled with American content: vernacular building traditions and preindustrial crafts.

SHEELER'S BARNS. By the late 1910s, Sheeler was deeply drawn to the historic buildings and artifacts of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he began spending his weekends. Living in an eighteenth-century farmhouse , he used photography to explore the play of abstract forms, light and shadow, and textures in the interior of the house. Vernacular structures such as barns (which he painted more than eighty times during his career) also offered the artist a readymade subject for exploring a familiar modernist concern: the ambiguous relationship of two to three dimensions. In Side of a White Barn (fig. 15.1), the arbitrary boundaries of the image, as well as the close focus on the plane of the wall, removed from any larger spatial context, frame our attention on the weathered surface and textures of knotted whitewashed pine board, lime plaster, and wood shingle. The effect, as the art historian Karen Lucic has pointed out, is to short-circuit the narrative associations brought by viewers to this familiar icon of rural culture, startling us into seeing the known and familiar with fresh eyes. The cubist geometries and varied surfaces of barns satisfied a desire to reconcile modernist form with historically meaningful subject matter. Critics saw in Sheeler's images an austere and plain-spoken style that was recognizably ''.American."7

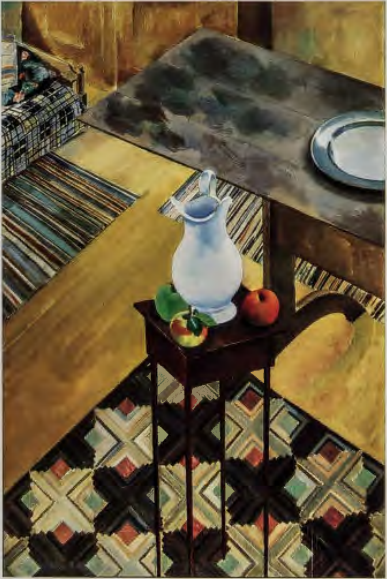

Throughout the 1920s Sheeler collected and painted early Americana, collaging the flat patterned surfaces of quilts, braided rugs, and Shaker artifacts into Cubist compositions without departing from his sharp-edged realism (fig. 15.2).

FOLK ART REVIVAL. The collector Hamilton Easter Field played a crucial role in this. expanding interest in folk art. Field's Ogunquit School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine ( established 1913) was a vital gathering point for modernists (including Marsden Hartley and William Zorach) looking to weathervanes, textiles, and other vernacular objects as models for their own formal experiments. By 1921, when Field compared an eighteenth-century colonial Dutch portrait to a late Picasso, his thinking had become symptomatic of a generation looking to root modernist formal values in the past. In the 1920s Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney exhibited folk art at the Whitney Studio Club (precursor to the Whitney Museum), and Edith Halpert opened her American Folk Art Gallery in New York City (1929), with works chosen 'because of their definite relationship to vital elements in contemporary American art." Anonymous works such as Mrs. Elizabeth Freake and Baby Mary (see fig. 3.13) gained new aesthetic appreciation from this generation. Electra Havemeyer Webb began a collection of quilts and folk sculptures that would become the Shelburne Museum in Vermont in 1947. The Polish emigre artist Elie Nadelman and his wealthy American wife Viola accumulated over 15,000 pieces of folk art beginning in the late 1910s. The impact of the expressive direct carving tradition of folk sculpture on Nadelman' s own work was profound (see Chapter 13).

If modernists found usable formal qualities in the folk arts of the past, others found in the same traditions a different "usable past" that validated their version of American history. Sheeler's patron, the industrialist Henry Ford, anchored the innovations of industrialism in Anglo-colonial America. Ford opened Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan, in 1929, an open-air museum of agricultural and manufacturing history that traced the nineteenth-century roots of the modern industry on view at Ford's state-of-theart River Rouge plant nearby. Emphasizing the tradition of "Yankee" ingenuity that connected colonial and nineteenth century inventors with twentieth-century industrialists, Ford's version of the past excluded the contributions of the immigrants who formed such a significant part of the work force at River Rouge. His anti-Semitic and xenophobic politics-he was a supporter of Hitler in the 1930s- underscore this version of an American past cleansed of all "foreign" influences. The oil magnate John D. Rockefeller was also deeply involved in both collecting and preservation. Rockefeller was the moving power behind the recreation of historic Williamsburg in the 1930s, where his wife Abby Aldrich Rockefeller's important collection of folk art would be housed. Banishing any reference to the slaves who formed fifty percent of the population of eighteenth century Williamsburg, Rockefeller's reconstruction was history from the top down, focusing on colonial elites.

THE DARK SIDE OF THE "FOLK." In both America and Europe, governments in the 1930s appealed to the "folk" - ordinary people whose virtues and traditions acquired new political authority on both the right and the left. In America, populism-the political appeal to everyday people-offered a platform of progressive change in the 1930s, but it shaded into dangerous forms of mass mobilization and mob violence in Germany, where Hitler's National Socialist (Nazi) Party propaganda manipulated faith in the Volk to create popular acceptance of institutionalized anti-Semitism. The United States had its own homegrown forms of collective madness; foremost among these was the practice of lynching.

In 2000 the New-York Historical Society opened an exhibition of lynching photographs entitled Without Sanctuary. The exhibition described the widespread circulation of postcards through the U.S. Postal Service, carrying horrific images, mostly of black men who had been lynched and often burned and mutilated as well. Not merely the work of a small band of hooded fanatics, lynching was a form of violence involving entire communities- men, women, and children. While these postcards were originally circulated to celebrate the intimidation of Negroes and mobilize a sense of community among white racists, today they are grotesque reminders of the reign of terror against black Americans in the era before Civil Rights.

The construction of the folk thus points in opposing directions. On the one hand, it was a way of supporting belief in the simple goodness of ordinary people, far from the corruptions of modern urban life. Yet on the other, it was also a concept that fomented mob violence directed at "outsiders" who were seen as spoiling the purity of the community.

The Regionalist Philosophy

"Folk" along with Native arts offered a vital example for another influential group of writers and thinkers in the interwar years: the self-described Regionalists, who emphasized cultural rejuvenation through the rediscovery of traditions grounded in the life, history, and landscape of a region. Regionalist philosophy addressed the concern that the repetitive labor required by mass production alienated people from meaningful work. Regionalism in the 1930s opposed the growing standardization of a national consumer culture that it perceived as homogeneous, placeless, and lacking roots. Instead, it sought cultural identity in the history, landscape, legends, and music of rural and small-town America. Shaped by a powerful reaction against uniformity, and an equally powerful longing for place, it discerned distinct regional identities in the South, the Southwest, the Northeast, and the Midwest. The Southwest, for instance, acquired its regional identity when influence from the East was strongest; the South's regional identity was formed in the decades after the Civil War, when it defended its distinctive culture against the incursions of the industrial North. The Regionalist movement in the Midwest reacted against the concentration of wealth and cultural resources in the East, insisting on the rural and small-town origins of national culture. Overall, Regionalists protested at the emergence of a mass public dulled by a national media, and seduced away from the core values of community by the lure of consumer goods and private pleasures. The recovery and promotion of regional identity in the 1920s and 1930s involved writers, artists, and social scientists. More than a style or subject matter, Regionalism was a philosophy.

COMMODIFICATION OF FOLK AND NATIVE ART. Native American cultures provided an example of a living folk tradition admired by Regionalists, in which basketry, pottery, weaving, and dance were practices that integrated the aesthetic, the spiritual, and the social. Such noncompetitive and communitarian practices linked the individual to the larger group in a network of shared meanings. Increasingly in the interwar decades, the folk came to represent for many American artists and writers a culture connected to place, and opposed to the slash-and-burn mentality of the pioneer. Americans disenchanted with the migratory habits of the current generation and the standardized products of consumer culture longed for objects that carried the patina of age and use; being tradition-bound came to represent a virtue.

The reinvigoration of democratic and populist ideologies in the 1930s further promoted interest in the art of the folk. Most influential was Holger Cahill's tellingly titled ''American Folk Art: the Art of the Common Man in America, 1750-1900," at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932, which opened its doors in the depths of the Depression. Cahill became a pivotal figure in Roosevelt's New Deal, which offered federal patronage for grassroots community based arts such as Appalachian music and New Mexican village arts.

Also part of the federal relief programs of the 1930s was the Index of American Design (from 1935 to 1941 a unit of the Federal Art Project, or FAP), which put some one thousand artists to work doing meticulous watercolors of about 18,000 folk and vernacular objects (fig. 15.3). The Index not only documented the regional diversity of American material culture from the colonial period to 1900, but it created a vital resource for American artists themselves engaged in the ongoing effort to create an American design tradition. Choosing watercolor over photography as a method of documentation enhanced the colors, shapes, silhouettes, and volumes of these objects and allowed artists to interpret them creatively. Documentation was the first phase of imaginative assimilation. The artist had to grasp the technical procedures and structural components of the object in order to reproduce them convincingly. The Index, now housed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. , remains the fullest survey in existence of America's material culture.

Patronized by collectors and museums, and nurtured by the federal government, folk and Native arts quickly became commodified. The folk aesthetic was used to sell a range of household goods. Ownership of such objects offered a quick ticket to the preindustrial past. The market extended into such areas as Appalachia, where baskets were turned out in mass quantities. Regional promoters meanwhile played down the hardships of life in Appalachia- terrible poverty, the lack of electricity, running water, and schooling. In the Southwest, a romanticized Hispanic and Native history coexisted with the economic marginalization of Pueblo and Hispanic citizens.

The Politics of Artistic Regionalism

In the years between the wars, Regionalism in the visual arts came to be most directly identified with a widely celebrated triumvirate of painters: Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and Thomas Hart Benton. Benton's self-portrait was on the cover of Time magazine in 1934. Dramatically varied in style, these artists shared a belief that art is most vital when it expresses the particularities of a locality. The Regionalism of Wood, Curry, and Benton also shared with other art forms in these decades between the wars a sense of art's obligation to shape popular histories, beliefs, and legends. Regionalism was about public memory and collective identity; artists were mythmakers, not only reflecting but also creating a sense of place.

Yet from the 1930s up to the present, the regional themes of Wood, Curry, and Benton have raised suspicions about their conservative social values and rejection of modernism. These suspicions first took shape in the charged international climate of emerging fascism. To some, Regionalism represented a dangerously isolationist, regressive, and anti-modern impulse in art that paralleled the Nazi art of the Third Reich. Regionalism and its foremost apologist, the art critic Thomas Craven, had set its courseagainst European modernism, with its formal distortions and anti-naturalistic interests. Its anti-modern stance linked it to the Nazi propagandizing against the "degenerate art" of the German Expressionists and other modernists.

Was there any validity to these claims that the Regionalists were first cousins to the blindly xenophobic artists who served Hitler's Reich? The questions are still debated, but the evidence suggests otherwise. All three artists called for an indigenous expression as far removed as possible from the abstractions of blind patriotism. Rejecting provincialism (a narrow attachment to one's place of birth), all three artists shared a belief that art stemmed from experience, and was most powerful when tied to what the artist himself knew directly. Despite their dismissal of modernism, Wood, Benton, and Curry were all urban trained artists who had traveled widely, studied the artistic traditions of Europe, and had an understanding of how painting had evolved since Impressionism. Wood's art is grounded in modernist design as influenced by Japanese woodblock prints and the period's streamlined stylization of form. Benton began his career doing abstract exercises in color and studies of Constructivist form. Critics missed the manner in which all three Regionalists commented often with biting humor- on the very social myths they were attacked for celebrating.

JOHN STEUART CURRY. An early Regionalist work, John Steuart Curry's (1897- 1946) Baptism in Kansas (fig. 15.4) complicates the picture of rural piety so frequently offered as a bedrock value of the American "folk. " Indeed, Edward Alden Jewell, a well-known art critic for the New York Times, read the painting as "a gorgeous piece of satire" on religious fanaticism. 8 It is difficult to see how anyone missed the satire, here or in other Regionalist works. The young woman, her hands clasped in prayer, is preparing to be immersed in a wooden trough-normally reserved for watering livestock-by a mustachioed preacher. Two doves plunge down from the light-streaked clouds above the scene, as in a baroque altarpiece. High religious drama is played off against the homely elements of the Midwestern farm scene. Curry's satire, however, is leavened by a touch of nostalgia for the communal piety signified by the closed circle of worshipers with their downcast eyes.

Modernization revived a taste for "old-time religion"; evangelical movements were widespread throughout the early twentieth century. Within the scene, the agents of the new urban order- automobiles, circled round the scene like prairie schooners, rural electrification ( electric wires in the background), and city fashions-all signal the forces of change at work in the American countryside. Is "old-time religion" the adversary of modernization, or its symptom? Baptism in Kansas gives evidence of both.

GRANT WOOD. American Gothic (fig. 15.5) is Grant Wood's ( 1891- 1942) humorous commentary on the puritanical streak in the American character. The prematurely wizened woman (based on Wood's sister) wears a cameo brooch whose image of a wood nymph-hair streaming out, full of natural fecundity, beauty, and grace-contrasts in every way with the wearer's spinsterish appearance. The board and batten farmhouse has the gothic tracery found in American rural wood structures as a distant echo of its European sources. Its American version, however, is altogether different. The farmer holds a pitchfork, repeated in the lines of his overalls, which he grips like a weapon. Everything associated with the two-except the worried glance of the spinster toward the left-is frontal, unflinchingly rectilinear; everywhere is a nature disciplined and straightened, forced to conform to the iron will of the American farmer, who brooks no whimsy. The same unflinching determination, in Wood's good-natured satire, drives the sallow-faced humorless pair who walk the straight and narrow way, closer to God but far removed from their own natures.

But American Gothic is also a tribute to the rural Midwestern heritage that produced Wood's own Iowa family. Wood's sources for the painting, as Wanda Corn has shown, ranged from blue willow-pattern chinaware to nineteenth-century daguerreotypes, Victorian prints, and premodern agricultural implements. The figures in American Gothic are the product of the same culture that produced the artifacts Wood admired and collected. Threatened by modernization, these older regional folkways and character types were ripe for literary and artistic treatment. The humor of the painting, as with much Regionalist humor, comes from a self-styled insider, not from the critical condescension of the outsider.

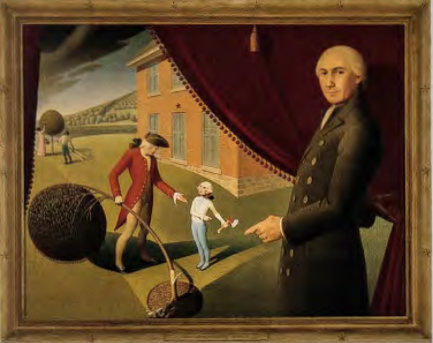

In 1939 Hitler invaded Poland, the opening act of World War II. In that year Wood painted Parson Weems' Fable (fig. 15.6). A child's storybook fable of exemplary honesty (George Washington as a child admits his naughty deed to his father), it was popularized by Washington's most famous biographer, Parson Weems, who stands outside the scene pulling aside a theatrical curtain. The head of the young Washington is that of Gilbert Stuart's famous painting of the first president as a bewigged old man-an iconic image universally known by its use on the dollar bill (see fig. 5.6). So wide was its circulation that Stuart's portrait has itself displaced in national memory the historical figure of George Washington as a young boy (or so Wood suggests). In the background of the scene, two slaves are shown picking fruit from a cherry tree, an allusion to the gap between myth and social reality in our national imagination.

Parson Weems' Fable calls attention to the ways in which our understanding of the past is mediated-literally framed-by representations, by stories within stories, like a series of Chinese boxes. With its toy-like landscape, deliberately naive presentation, and tale-within-a-tale structure, Parson Weems' Fable reveals how we construct our national myths, and witnesses the framing power of stories and legends in shaping our collective identity. Unlike the painters of the German Reich, Wood recognized the "folk" as an invented concept, the product not of some essential race identity grounded in the soil, but of stories told and retold, tales whose "authenticity" was itself a product of a nation-state that required unifying myths. Parson Weems' Fable pointedly exposes the mechanisms of cultural myth rather than presenting them as transparent truths. Among those who collected Wood's work were a number of Hollywood actors and directors, who, like him, engaged myths with humor and irony.

THOMAS HART BENTON. The best known of the trio of Regionalist painters, Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975) was also the most widely attacked. His style-like himself was full of swagger. Robust in its swelling volumes and baroque curves, it bordered on caricature, which brought angry denunciations when it came to ethnic depictions. Benton, who was highly articulate, scrapped with his critics and was unapologetic about his murals painted for a broad public, among them America Today (1930); The Arts of Life (1932); and A Social History of Missouri (1936), done for the House lounge of the State Capitol in Jefferson City.

Benton considered A . Social History of the State of Missouri his best work. Here as elsewhere he created a fluid montage of figures and episodes, condensing past and present, history and fiction, into a seamless unity. Yet his dynamic composition results in an open-ended narrative that engages each viewer's own version of the past: history as story-making, in short. On either end of the room Benton featured Huck and Jim from Mark Twain's great novel of the Mississippi, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (fig. 15.7), and a scene from the ballad of "Frankie and Johnnie," showing a crime of passion in a saloon. Here, as in other public murals Benton painted in the 1930s, he gives to literature and legend the status of folk epic, recognizing their role in shaping regional identity. History is revealed as part myth, while regional lore is historicized. Benton's montage technique resembled the new form of visual modernity evident in tabloid journalism and in film editing. Indeed, the artist had considerable interest in the film industry; he visited Hollywood in 1937, where he produced some eight hundred drawings. Benton's History of Missouri is mostly devoid of great men, favoring instead the everyday farming, family life, political campaigning, industry. Scenes in the mural bluntly acknowledge racism (a slave auction and a lynching), criminality (the James brothers), and exploitation (in a scene where an early trader trades whisky for Indian blankets).

Speaking to the 1930s' need to reengage history and everyday experience, the Regionalist art of Curry, Wood, and Benton was ultimately discarded by the turn toward abstraction and a language of universal forms in the following decade. In 1949, Life magazine posed the question as to whether Jackson Pollock (1912-56)-Benton's former student, who had long since repudiated his teacher's art-was "The Greatest Living Painter in the United States." Pollock's own career reveals the transformation of mythic content from the social to the psychological (see Chapter 17)

Art Colonies and the Anti-modern Impulse

Many readers today carry an image of New Mexico seen through the lens of Georgia O'Keeffe's now famous paintings. First introduced to New Mexico by her friend Mabel Dodge Luhan in 1929, O'Keeffe spent the rest of her career focusing on the wind-carved stark landscapes of northern New Mexico near her home in Abiquiu. But O'Keeffe is only the best-known of an extensive colony of artists drawn to New Mexico by its particular blend of austere beauty, premodern village life, and Pueblo and Hispanic spirituality. Beginning in the 1890s, artists from the East flocked to Taos and Santa Fe in northern New Mexico. Culturally remote from the Euro-dominated eastern half of the nation, New Mexico was, as Charles Lummis put it, "the United States which is not the United States." Spanning the spectrum from academic to modernist, these artists struggled to anchor the lessons of their European training in native themes. The peasant cultures of Brittany had furnished subject matter for American artists working in France. Returning to the United States, they responded eagerly to the possibilities presented by the Pueblo Indians and Hispanic villagers of the Rio Grande Valley, whose lives seemed to embody a timeless round of earthbound ritual and communal piety.

From the Renaissance to the "new age" movements of the late twentieth century, Europeans have romanticized Native cultures as embodying virtues their own societies were lacking. We have seen instances of this identification, from Benjamin West's admiration for the Mohawk of Pennsylvania (see fig. 4.35) to Catlin's career-long devotion to documenting embattled Plains cultures in the mid-nineteenth century, to Frank Hamilton Cushing in the 1880s (see fig. 11.16). White identification with the indigenous, however, acquired new intensity between the wars, furnishing a way of exploring alternatives to the cultures of modernity. "I have done everything . . . except lash myself and carry a cross," wrote Mabel Dodge Luhan, former New York hostess of the avant-garde, in a letter about the Penitente practices of the villagers in northern New Mexico where she moved in the 1910s. International interest in the culture of the Pueblo Indians prompted Carl Jung, the influential Swiss psychologist and student of cross-cultural myth, to travel to New Mexico in the 1920s, a trip that helped inspire his later ideas about the need to balance Western rationality with intuitive, non-rational approaches to knowledge. The English novelist D. H. Lawrence, who spent his later life in New Mexico, lamented that Americans "have buried so much of the delicate magic of life."

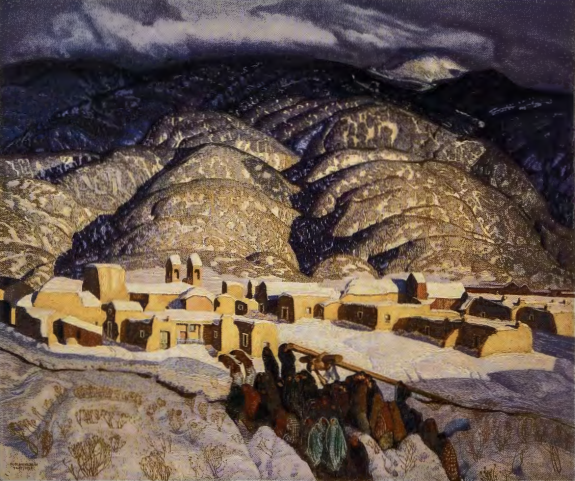

In Ernest Blumenschein's (1874-1960) Sangre de Cristo Mountains (fig. 15.8), a procession of Christian penitents winds its way up the path of the Cross, reenacting the passion of Christ in a yearly drama. Blumenschein's northern New Mexico villagers act out their communal ritual of penance in stylized gestures of grief. The figures recall centuries of Christian imagery. Three bare-chested men lead the way, the third bowed beneath a massive wooden cross which he drags toward the site of the crucifixion. Earth-colored adobe buildings occupy the middle distance. Filling the upper half of the canvas are the Sangre de Cristo ('blood of Christ") Mountains of the title, deeply creased by snowy ravines. The rounded, weathered natural forms of the mountains offer a grandiose symbolic frame for the local human action in the foreground. Blumenschein has simplified and reduced a complex landscape in order to emphasize the congruence of human and natural, the timeless rhythms of village ritual and the cycles of the seasons. His formal simplifications, the anonymity of his faceless penitents, and the suggestion of universal meanings in the drama of village life, all link the artist to earlier European interest in peasant and preindustrial cultures. The offspring of such paintings are found everywhere today in the galleries of Santa Fe.

Romantic Regionalism in California and New Mexico

Interest in the Spanish legacy of the Southwest was one of a series of romantic revivals beginning in the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century, the Pueblo and Mission revivals found their place within a broader national (indeed international) movement to recover the artisanal and communal building traditions identified with the origins of national cultures. Nationalistic pride played a role in these historical revivals, which were celebrated as "straight from our own soil" and "a true product of America."

Romantic Regionalism brought together businessmen, architects, and regional promoters around a picturesque vision of a premodern past before the arrival of the Yankees. It may seem paradoxical that these very Yankees were responsible for shaping a regional image so indebted to a time before they arrived. The fascination with the premodern era-here as elsewhere in American arts and culture often accompanied and even facilitated the process of modernization by offering an imaginative retreat from the pressures of the present.

"MISSION REVIVAL'' STYLE. California led the way in exploiting its Hispanic heritage. At the Chicago World's Fair or Columbian Exposition of 1893, state pavilions were designed in a range of regional styles: plantations for the South, for example, and Spanish Mission styles for the California Building (identified by red-tiled roofs, arcades, stuccoed walls, and asymmetrical massing). By 1915, at international expositions held in San Francisco and San Diego, the Mission style had become the official expression of California's regional identity. In the years after statehood in 1912, New Mexicans developed their own versions of the "Mission revival," inspired by the ancient cliff dwellings and historic Pueblo villages of this region.

The "Mission myth" of an exotic Hispanic and Indian heritage had several major components, as outlined by the historian Mike Davis: a peaceful population of Mission Indians living in harmony with their European conquerors, and a colorful Mexican population who passed along their music, carefree ways, and picturesque buildings to the more dynamic Euro-American cultures that took their place. The Mission myth transformed the region's troubled history of forced Native labor on the Missions into a fantasy of caballeros and dark-eyed senoritas. For generations of Californians, the curved gables, red-tiled roofs, bell towers, and arcaded plazas of Catholic Missions became for the West Coast what the Colonial Revival was to New England and plantation-style homes were to the South: a means of instant access to a romantic past, remote from the present.

One of the primary figures behind the creation and promotion of the regional myth in California was actually from Ohio. Charles Lummis (1859-1928), a young journalist, had walked to Los Angeles in 1884 in search of a better climate and improved health. In his writings and activities as an editor, amateur archaeologist, founder of the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, and preservationist, Lummis helped spawn a new regional consciousness among wealthy exiles from the East. Lummis was at the heart of the region's first literary and artistic vanguard, centered along the Arroyo, a wooded gulch set against the dramatic backdrop of th~ San Gabriel Mountains in Pasadena. Drawn by the healthful Mediterranean climate of the region, Lummis constructed a baronial home for himself with the invented Spanish name of El Alisal (1897-1910), built of boulders hauled up from the dry creek bed by the labor of Pueblo Indians imported from New Mexico (fig. 15.9). Combining such picturesque features as a defensive tower, a Mission-style gabled wing with hanging bell (inspired by the newly restored Mission San Gabriel nearby), and hacienda-like main house, and surrounded by indigenous plantings, El Alisal expressed a widespread fascination with California's Hispanic past, filtered through an image of Spain's aristocratic Old World culture. In his home, life, and writings, Lummis helped foster the regional myth that would shape the restoration of California's Franciscan Missions in the early twentieth century.

"PUEBLO REVIVAL'' OR "SANTA FE" STYLE. In the 1850s Jean-Baptiste Lamy, archbishop of Santa Fe, newly arrived from the East, campaigned to obliterate the art of the santeros. For him this was a shameful reminder of the barbaric conditions of a frontier society that his enlightened leadership would soon leave behind. Half a century later, attitudes toward the Hispanic heritage of the Southwest had radically changed. As in California, architects, preservationists, and civic promoters now turned to the Spanish and Native history of the region for a romanticized regional image: "One must go to New Mexico to find an American architecture and an American art."9 Promoters celebrated the Southwest for its archaic and spiritual intensity. In the decades between the wars, tourists from the East flocked to New Mexico and Arizona in unprecedented numbers, in search of ancient mysteries and legendary histories. Indigenous ruins dating back ten centuries offered parallels to the great ruins of Old World civilizations, and captured Americans' romantic longing for a deep history that would counter claims of their nation's cultural shallowness.

In New Mexico, the "Pueblo" style-drawing on the massive simplified adobe contours, wooden beam construction, and battered and buttressed walls of such buildings as the church of San Esteban at Acoma Pueblo (see fig. 2.31)- fused Native and Hispanic adobe building traditions in a distinct architectural image. San Esteban served as the source for the architect Isaac Hamilton Rapp's (1854-1933) New Mexico state building at the San Diego exposition of 1915, and later for the Museum of New Mexico building in Santa Fe (fig. 15.10). The architects Charles Whittlesey and Mary Colter (1869-1958)-whose 1904 Hopi House perched on the rim of the Grand Canyon-drew inspiration from the multi-storied buildings of the Hopi and other Pueblo peoples.

In America's first restaurant chain, the Fred Harvey Company furnished travelers on the Santa Fe Railroad with not only good food but a romanticized regional image drawing on Hispanic and Indian elements (fig. 15.11). Building on its Hispanic past, Santa Fe changed street names from English to Spanish in these years.

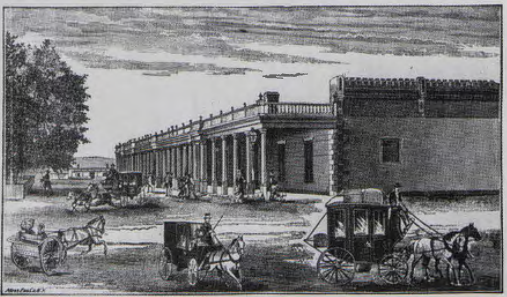

THE BIOGRAPHY OF A BUILDING. Buildings, like the people who make and use them, have biographies. They carry their histories with them, though it takes some digging to recover these histories. The Palace of the Governors on the central plaza in Santa Fe (fig. 15.12) is a much beloved icon of New Mexico's regional Hispanic heritage. But the building tourists encounter today dates largely from 1913, and represents what has come to be known as the "Santa Fe style." In the early twentieth century, regional promoters, architects, and city fathers devised a style of softly modeled adobe construction, complete with covered walkways, or portals, and projecting ceiling beams, or vigas, that combined indigenous Pueblo forms in use for nearly a millennium with Hispanic adobe building originating in the seventeenth century. The 1913 building was intended to give a recognizable and picturesque look to Santa Fe, increasing tourism to the city. Indeed, it has become the legislated style for use in the historic city center.

The 1913 building itself replaced a structure from the late nineteenth century that had a very different architectural heritage (fig. 15.13). Known as the "Territorial style," it reflected the influence of the newly arrived railroad linking the remote Southwest to eastern markets and architectural styles. The Territorial style included prefabricated pedimented window surrounds, as well as brick coping at the roofline, giving a sharper, more classical profile to adobe construction, and carrying with it the message of eastern civilizing influences domesticating the rough wood and clay vernacular forms associated with Hispanic and Pueblo New Mexico. This building embodied the tastes of a generation of non-Spanish European-American businessmen for whom the associations with Indian and Hispanic traditions were liabilities and not- as they would become in the early twentieth century- the source of a romanticized regional identity.

Beneath these historical accretions of style and taste lie parts of the original 1610 building that occupied the site when the town became the capital of the northernmost province of New Spain. This was a somewhat nondescript adobe structure flush with the street, containing a simple portal and situated at the north end of the central plaza as dictated by the administrative laws of the Spanish empire in the New World. The building combined a garrison with a residence for the governor, and had itself incorporated the puddled walls of a Pueblo structure predating Spanish occupation. Which of these various versions of the Palace of the Governors is the "real" one? To which should we accord pride of place in recounting the history of Santa Fe as regional capital? Focusing on only one version of the building has the effect of overriding the previous histories it has embodied.

Norman Rockwell:. Illustrator for the American People?

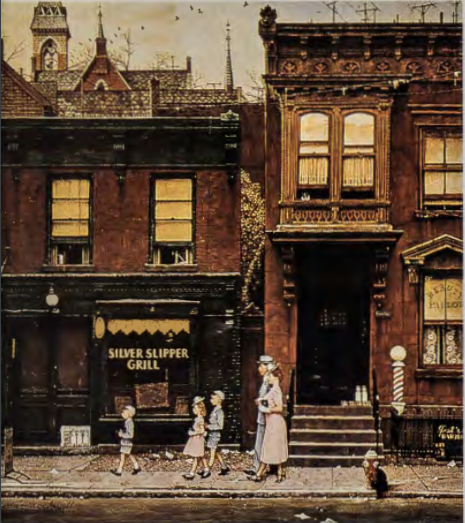

Belief in the continuity between past and present is a critical ingredient of a "search for roots." A sense of continuity with the past helps maintain stability in the midst of change. Beginning in the 1910s, the illustrator Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) gave this to mass audiences in abundance. In Rockwell's America, cars, television antennae, and other complications of modern life are framed and defined by the persistence of the past, which lies reassuringly just beneath the thin veneer of modernity. In Walking to Church (fig. 15.14), the decay of American cities resulting from the 1950s flight to the suburbs offers a picturesque backdrop to the white nuclear family who proceed, Pilgrim's Progress- style, through a vale of urban woe on their way to church, oblivious to their surroundings. Rockwell visually puns on their "righteous course" with a series of parallel planes that connect them to the roof and steeple of the background church. Commercialism, consumerism, standardization- decried by cultural critics throughout the twentieth century-are background influences woven into Rockwell's easily recognizable dramas of everyday life.

Rockwell is one of a handful of household names among America's image-makers who are broadly familiar to the general public. Yet, until recently, those who were serious about fine art-critics, museum curators, men and women of "taste" -would have nothing to do with him. He was maligned for giving audiences what they wanted a vision of a national life that never existed-rather than confronting them with difficult dilemmas ( although he did take on race prejudice and the Civil Rights movement in a series of late works). In addition, he was merely an illustrator; most of his work was done for the Saturday Evening Post, a mass circulation middlebrow journal for which he produced 322 covers between 1916 and 1963. Rockwell photographed "on location" and then obsessively recreated scenes in the studio by working from photographs and live models. His critics believed that illustration required less skill than art: modern artists transform reality rather than merely mirror it. Yet the notion that illustration-and artistic naturalism more generally-is less "artful" than other forms of image-making is belied by Rockwell's compositions. He shows us not the way things were, but the ways in which many Americans wanted to believe they were. Whatever the value of his art, his illustrations, with their wealth of meaningful detail ( clothing, posture and gesture, facial type, domestic and urban backdrop), reveal the elements of Rockwell's America and why it proved so compelling to his public.10

Rockwell's images embodied "The American Way of Life," a populist notion of shared national character and core values. His magazine covers (often reprinted as posters) speak in a voice of social inclusiveness and shared humor. They imply a confidence that, confronted with the situations shown, we will respond the same way as Rockwell's subjects themselves. In Saying Grace (fig. 15.15), differences between generations, between rural and urban, and between traditional and modern America are bridged in an image intended to tap universal emotions inspired by everyday acts.

Rockwell's exacting realism gave his depictions a feel of authenticity. From the 1930s on, his work enjoyed such wide circulation that at times it seemed to take the place of lived memories, reshaping the recollection of national life. Like the family snapshot that stands in for, and ultimately replaces, the actual event, his illustrations have, for many Americans then and now, become "our America." Yet those who do not recognize Rockwell's America as theirs feel a sense of alienation: "Where am I in this picture?"

Paradoxically, Rockwell's rise to fame between the world wars coincided with a time of unprecedented movement away from the ideals his images represent: smalltown, face-to-face, rooted in stable social identity. In his upbringing, Rockwell himself had little direct experience of the small-town life he depicted on the covers of the Saturday Evening Post. His nostalgic vision was avidly consumed by millions of Post readers, yet the Post was a part of the national media, the newspapers and broadcasting, that were displacing regional and local identity. The consumer culture advertised by mass circulation magazines was taking the place of the older way of life commemorated in Rockwell's images. His appeal to the purportedly universal elements connecting people across class, regional, and ethnic lines was something that linked him to other purveyors of mass culture, such as his friend Walt Disney.

Was Rockwell merely pandering to his audience's desire for an America out of which all unpleasantness had been imagined away? Or did he, as his defenders suggest, build on pride in the inheritance of democratic values: selfreliance, belief in community, and determined pursuit of one's dreams? And why were these values so often linked to an old-fashioned version of America rather than to its contentious present?