14.1: The Skyscraper in Architecture and the Arts

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

"Squares after squares of flame, set and cut into the ether. Here is our poetry, for we have pulled down the stars to our will" -Ezra Pound, "Patria Mia" (1913); from Ezra Pound: Selected Prose, 1909--1965, p. 107.

It is impossible today to write about the upward thrust of America's urban skyline with the same innocence, idealism, and romance that inspired Ezra Pound's 1913 tribute to the New York night. Pound's words recall the impossible reach and godlike energies symbolized by the nation's first skyscrapers. Such romantic dreams faded long before the horrific spectacle of September n, 2001, when the twin towers of the World Trade Center-like pillars at the entrance to Manhattan's financial district, symbols of the nation's commercial power and financial reach-were toppled into rubble and carnage beyond our wildest nightmares. In the aftermath of that event, it is easy to forget the complex cultural meanings originally embodied in the skyscraper.

By the early twentieth century, the skyscraper had already become the preeminent symbol of America's ascendancy As the most conspicuous feature of the new American city, the skyscraper was distinctively American, a form mostly absent from European cities, where the urban fabric dated back centuries. European admiration for these new forms relieved the longstanding sense of inadequacy Americans had felt in the eyes of Europe. Although skyscrapers embodied the modernist romance with aviation, soaring height, and freedom from limits, nevertheless, with few exceptions, American skyscrapers were sheathed in historical forms. The best-known architectural competition of the 192os-for the Chicago Tribune Building (fig. 14.1)-passed over numerous modernist designs submitted by Walter Gropius, Bruno Taut, and other Europeans in favor of a neo-gothic solution by American architects Raymond Hood (1881- 1934) and John Mead Howells (1868-1959), complete with a crown-like top, flying buttresses, and piers running the shaft of the building. In the eyes of its proprietors, these decorative details suffused the Chicago Tribune Building with the poetry of history. The moguls of modern media were not quite ready to adopt architectural modernism.

Cultural critics debated both the necessity for the skyscraper and the form it should take. For urban visionaries like Ayn Rand (1905- 82, author of The Fountainhead, published in 1943), the skyscraper was an emblem of heroic will and the ultimate demonstration of modernity's utopian promise. For skeptics like the writer and critic Lewis Mumford (1895-1990), the skyscraper represented a colossal waste of resources and an expression of hubris that would bring countless environmental problems in its wake. In addition, while conforming to the street grid, skyscrapers generally ignored their context, thereby neglecting the social life of public spaces and disrupting older, more use-oriented patterns of movement. Turning their back on the street, skyscrapers instead created fantasy worlds within.

The skyscraper came to symbolize the triumph of American capitalism, as expressive of the era of big money as temples were of the ancient world, or cathedrals of the Middle Ages. The collapse of the stock market in 1929 inevitably brought a dramatic shift in perspective; the New York designer Paul Frankl (1886-1958) proclaimed the Empire State building "the tombstone on the grave of the era that built it."1 Yet the skyscrapers that redefined the look of the American city were far more than monuments to business and the spirit of commerce. On one level their form was generated by the logic of profit (building up rather than out in the high-rent urban core). Yet in their decorative schemes they represented culture by evoking ancient symbols, distant times and places. Their ornamental details and decorative interiors offered magic carpet rides across time and space. To enter the lobby of a skyscraper from the 1920s or 1930s is to find oneself in a dimly lit fantasy world, surrounded by stylized metalwork and extended friezes in which the forces of nature are displayed in a playful storyline of unfolding life. The imagery of the nation's skyscrapers in the 1920s and 1930s takes in everything, from the underwater world to the heavens, freely associating East and West, past and future, labor and capital, the Greek gods and the gods of commerce. The imagination is transported beyond the flatfooted realities of present-day business and into sensuous realms where chiseled bodies display their gifts, linking business to humanity's oldest urges. Ambition and arrogance are redeemed; the empire-builders of the present day are linked to Prometheus, who defied the gods to bring fire to humanity. The business conducted within is blessed by fleetfooted Mercury, the god of commerce.

Perhaps no other skyscraper has acted as such a springboard to fantasy as the Chrysler Building (p. 450) in midtown Manhattan. Instantly recognizable, it makes an appearance in Joseph Cornell's portrait of Lauren Bacall (see fig. 14.34); the artist Matthew Barney (b. 1967) staged an entire episode of his film Cremaster Cycle (1994-2002) in its interior spaces. Like other buildings of these years, it is tripartite in form: a base of twenty stories with one setback, a shaft that sets back twice before a rise of twenty-seven more stories, at which point the tower begins its inward taper with a cascade of arches in sunburst formation, sheathed in stainless steel punctuated with chevron windows. For a brief period the tallest building in Manhattan, it was soon surpassed by the Empire State Building; together the two buildings still define the midtown skyline. With its stylized eagle gargoyles sixty-one stories up, and its four winged Mercury helmets (the hood ornament on the Chrysler car) at the thirty-first floor, along with a frieze of automotive hubcaps, the Chrysler Building offers a compelling display of urban theatricality, eclectic borrowing, and decorative fantasy from the corporate age. Its ground floor lobby (fig. 14.2) enfolds the urban voyager in a sensuous realm of exotic woods and Moroccan marble, Mexican onyx, and German travertine, elaborately inlaid in chevrons, zigzags, and other Art Deco motifs deriving from American Indian cultures, while suggesting the global reach of American commerce. On the ceiling is a mural of the building's construction, full of muscled men. The Chrysler Building is a monument to one man-Walter P. Chrysler- a self-made ·titan of the automotive industry whose first set of tools was enshrined like a holy relic in a glass case beneath the building's spire. Chrysler (1875-1940) was legendary for having demanded-and received-$1,000,000 a year as president of one of the large automotive companies in 1920. The Chrysler Corporation weathered the Great Depression when many other companies failed. Perhaps the Chrysler Building's greatest appeal is that it celebrated individual achievement in the era of big money.

Designing for Modernity: The "Moderne" Style

Standardization and the mass production of everyday goods lay at the heart of America's rise to industrial preeminence in the twentieth century. Yet it was some time before an aesthetic expression of the new industrial modernity emerged to give American design a distinctive voice. Despite calls for reform during the Arts and Crafts movement of the later nineteenth century (see Chapter 10), American manufacturers continued to use mass-production techniques to replicate historic styles. Therefore, while America's emerging modernist artists might celebrate the industrial modernity of American skyscrapers and mass production, nevertheless most Americans lived out their lives in late Victorian domestic environments. As late as 1925, Paul Frankl wrote that "we have no decorative art." So poor was the level of American design that the nation was not even represented at the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, held in Paris in 1925 (the event that originated the term ''Art Deco"2).

LUXURY INTERIORS. Following this embarrassment, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover created a federal commission to encourage design innovation. The situation turned around so quickly that by 1928 Richard Bach of the Metropolitan Museum of Art could write, "The modern style ... has come to stay."3 American Moderne, or Art Deco, as it came to be known, was associated with the disjunctive rhythms of machinery and the stylized contours of the urban skyline. Art Deco extended across the decorative arts, architecture, furnishings, and luxury items from cigarette cases to evening wear. Its clean lines, industrial metals, and stylized silhouettes, though often handcrafted, evoked machine fabrication. Considered a masterpiece of Art Deco, the Chanin gates from the Chanin Building in midtown New York City (fig. 14.3) use the stylized forms of Art Deco-spirals, vectors, jagged bolts, zigzags, and concentric circles linked by ray lines that give the design a futuristic look. Organic swirls jostle gear-like machine parts, while the entire gate is supported by spindly stacks of coins, a sly allusion to the money that underwrote the glamorous new modern city and provided the patronage for such buildings as the Chanin and the Chrysler.

GLAMOROUS GARMENTS. The Art Deco style was also associated with custom-made luxury goods such as this evening wrap of c. 1928 (fig. 14.4). The patterns on this formal coat- its chevrons and vectors suggesting rocket-like propulsion---capture the dynamic forces of the physical world, both human and natural. Three-dimensional extruded forms resemble crystals, which-steely hard, untouched by time-serve as prototypes for the skyscraper. Geometric shapes-hexagons, circles, and spirals- evoke inorganic nature. American Art Deco controlled and structured the surging energies of modernity, embracing nature and science. But it also incorporated the anti-naturalistic geometries of Egyptian and Native American arts, drawing upon formal similarities between Pueblo pottery and Navajo weaving, on the one hand, and the angular precision-cut qualities of new technology on the other. It reconciled desires for a footing in the past with a longing for the glamor of the future, fed by modern materials such as plastics, chrome, and stainless steel. In this combined appeal to both modern and "primitive" elements, Art Deco resembled jazz-a musical language many critics of the time associated with both the pounding rhythms of modern machines and the "tribal" rhythms of Africa.

Cubism in the American Grain

American artists were quick to exploit the aesthetic possibilities of the skyscraper and the new urban environment that resulted from the "skyward thrust" of American building. However, the necessities of photographing or painting a tall building require a radical readjustment of perspective. Standing on the ground looking up at twenty or thirty stories, one's orientation to a vanishing point located on a horizon line disappears and the ground plane now becomes flat in relation to the recessional spaces of the city. Avenues shoot diagonally across the plane of representation rather than receding into an illusionistic distance. This ambiguity between two and three dimensions was an essential feature of European Cubism. Modernist artists and photographers embraced this disruption of perspectival space, unlike late-nineteenth-century artists, who retained a traditional sense of perspective by painting the skyscraper from a distance (see fig. 10.6). With time, modernist forms of urban representation-faceting to suggest passage between two and three dimensions, sharp diagonals, and radically tilted ground planes-entered advertising and graphic design, popular filmmaking, photojournalism, and even vernacular art.

THE VIEW FROM THE TOP. Some critics, concerned that American art would forever remain tethered to Europe, found hope for an original American modernism in the American skyscraper city. American artists no longer needed to copy Europeans. As they were quick to point out, the urban environment itself promoted radically new ways of seeing. The camera proved especially responsive to these fresh pictorial possibilities. Alvin Langdon Coburn's (1882-1966) The Octopus, New York (fig. 14.5) is a view of Madison Square, taken from the Metropolitan Life Building, whose shadow cuts diagonally across the frame. Leafless winter trees on a field of white snow appear like spidery veins around the oculus of a great eye. The city is splayed out before the viewer perched high above. The perspective here resembles that of John Marin, whose Lower Manhattan (Derived from Top of the Woolworth Building) also reorganizes the visual prospect from a point high above the street (see fig. 12.21). From this high perspective, the horizon disappears completely and the ground appears as a flat plane. Coburn's movement beyond photographic illusion into abstract design was encouraged by his study with Arthur Wesley Dow, whose emphasis on Japanese design and pattern informed Coburn's tilted-up ground plane and flattened perspective. Coburn's image further anticipates the photography of such European artists as Andre Kertesz (1894-1985) and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) in the 1920s, who commonly shot the ground plane from above. The effect of this new photographic perspective was to isolate fragments of the -city from their urban context. Displaced from the ground plane, recognizable elements are resituated in abstract compositions of shape and form.

CUBISTIC CAMERAWORK. Proponents of American art in the 1920s-intent on throwing off European influences found in the disorienting perspectives of the American city a way to be both American and modern. American Cubism, they pointed out, saw things straight, unlike its French version, which manipulated and reordered the components of nature in the studio. By the 1920s, this Cubist perspective on American cities was fully domesticated in the work of Charles Sheeler and others; Sheeler demonstrated that Cubism existed in nature, merely awaiting the selective eye of the photographer or the artist. Sheeler and Paul Strand (1890-1976) collaborated on one of the earliest film portraits of the modern city, Manhatta (fig. 14.6). The seven-minute silent film is composed of long static shots of the dynamic metropolis. These are edited to create a visual montage of the city, with a narrative held together by superimposed quotes from the nineteenth-century New York poet Walt Whitman, whose embrace of modern life and visionary voice inspired many modernists. Throughout the film, the camera becomes an instrument of visual exploration and experimentation, sharply angled up or down, creating a montage out of discontinuous visual fragments, and playing with the ambiguity between the flat ground plane and the recession into depth. The film's beginning and its ending, however, offer a broader frame that unifies the modernist montage of the city: the opening shot is a heroic prospect of the urban skyline from the Staten Island ferry, while the closing shot surveys the Hudson River, looking toward the Atlantic world beyond the island. This encompassing gaze returns to older visual traditions of the framed view and functions as well to integrate city and nature.

Stills from the film later served Sheeler as sources for his Church Street EL (fig. 14.7). Here the ground seems to be on the same plane as the elevated rail, seen "in plan" as a diagonal shape on the right side of the canvas. Sheeler translated the tonalities of the black and white film into unmodulated planes of color that enhanced the sense of abstract pattern.

The Skyscraper City in Film

From the era of silent film through the end of the Depression, the dreams and challenges of the modern city were the subject of countless films in which the skyscraper served as a symbol of cultural ambivalence. From Fritz Lang's (1890-1976) Metropolis-a German film of 1926 inspired by the skyscraper city of New York-to the Emerald City of The Wizard of Oz (1939), the modern city suggested a new world free from the wreckage of history. It was a vision, however, that frequently dissolved into troubling tales of oppression (as revealed in the city of workers beneath the glittering metropolis of Lang's film) and disappointed dreams. For many Americans in the interwar years, the city promised wealth, opportunity, and a vast array of consumer goods. For others, it symbolized moral corruption and the hubris of America's business culture, as well as the dissolution of regional differences in a standardized landscape-the creation of an economic order at odds with everyday lives and sentiments.

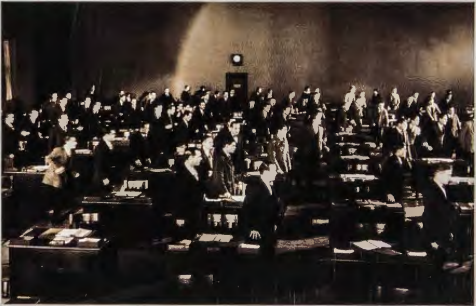

A series of films suggests the range of meanings the skyscraper embodied in the 1920s and 1930s. In Harold Lloyd's (1893-1971) Safety Last of 1923 (fig. 14.8), a young man from small-town America scales a ten-story building in downtown L.A. in an effort to win the stunt money he needs to marry his sweetheart. His act takes the skyscraper's association with social and financial ambition literally, while Lloyd's everyman figure reassuringly links the nation's small-town past to its big-city future. The Crowd by King Vidor (1894-1982) (fig. 14.9), though only a few years later, is a far more caustic film that dwells not on the continuity between past and future but on their rupture. The young man from the small town confronts the visionary prospect of the city at the film's opening. Its cloud- aspiring towers recall the opening shots of Strand' s and Sheeler's Manhatta. Yet after this heroic beginning he experiences a series of tragic disappointments in his struggle to realize his dreams. The skyscraper in Vidor's film is an emblem of gridded conformity and ruthless oppression memorably captured in a crane shot that moves up the full height of the building (in reality a model) and then dissolves into an office interior of row upon row of men at desks. The work grid finds its echo in the film's final image of endless gridded rows of filmgoers anesthetized by mass entertainment, linking the parallel worlds of work and leisure. In Baby Face (1933), Barbara Stanwyck (1907- 90)- the tough-as-nails, self-made woman at the film's center- literally sleeps her way to the top, occupying successively higher floors of the skyscraper that houses her corporate lovers. The innocent American ambition of Harold Lloyd's boy from the country has become a craven quest for social power, epitomized by the "view from the top."

The cynicism of filmmakers in the 1920s and 1930s was transformed once again into idealism in the ultimate skyscraper film: King Vidor's The Fountainhead, based on a novel by Ayn Rand. A celebration of titanic male will inspired by the figure of Frank Lloyd Wright (who, ironically, built only one skyscraper, in Bartlesville, Oklahoma), the film saves the skyscraper from its damaging associations with corporate power and restores it to the creative control of the architect as modernist visionary.

Imaginary Skyscrapers and Visionary Artists

Modernist visionaries corrie in different guises. The work of two artists outside the mainstream art and culture system reveals the ways in which the modernist idea of the skyscraper percolated into the imaginations of everyone in the first half of the twentieth century, and sometimes was expressed in offbeat and grandiose ways.

Y.T.T.E. Achilles Rizzoli (1896-1981) was born in Marin County, California, to a Swiss dairy-farming couple. In making the fantastical architectural drawings for which he is famous he drew upon his training in the Beaux Arts style of architectural rendering at the California Polytechnic College of Engineering. Rizzoli worked as an architectural draftsman for most of his adult life, and his art reflects his skill at hand-lettering and at precisely rendering buildings with a compass, straight-edge, and triangle. The buildings that he drew with fanatical precision at home (many of the drawings are up to 5 feet tall) were far from standard Beaux Arts temples and towers. They were symbolic portraits of the people to whom this painfully introverted man wished to reach out. Shirley 's Temple (fig. 14.10), done in 1939, was a play on the name of the famous child movie star of the 1930s and 1940s. It was intended as a homage to a neighbor's child, Shirley Jean Bersie, who was interested in his art. In other drawings, the artist rendered his mother-to whom he was slavishly devoted for his entire life-as a Gothic cathedral.Rizzoli saw visions and heard voices. He called himself "the architectural transcriber of the divine." He worked for many years on plans for his own private world's fair, recalling the splendors of the 1915 Panama Pacific Exposition in the San Francisco of his youth. A private abbreviation, "Y.T.T.E.," lettered on many of his drawings, gives insight into the role obsessive art making had for this troubled recluse: "Yield To Total Elation." And so he did, in the fantastical creations of his pen and his brain.

SIMON RODIA'S WATTS TOWERS. Unlike Rizzoli, Simon Rodia (c. 1879-1965) designed and executed his architectural fantasy in three dimensions, and in a public, urban space (fig. 14.11). Born in Rome, Rodia emigrated to the United States as a child, and earned his living as a tile-setter. Like Rizzoli, his visionary art drew upon the skills of his trade. Starting in 1921, in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, Rodia began to build a series of towers out of steel reinforcing rods covered with wire mesh and daubed with cement into which he embedded sea-shells and broken tiles, dishes, and bottles, as well as other cast-offs. The tallest tower is nearly mo feet high, built without benefit of scaffolding. A series of fountains, archways, and paths enclosed by a wall completes his architectural fantasy. After laboring upon his creation for thirty years, in 1954 when he was in his late seventies, Rodia gave his property to a neighbor and moved away, his work complete.

Simon Rodia's Watts Towers, which was slated for demolition in 1959, became the first such environment to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and to be declared a National Monument. In the center of what is today an African American neighborhood of low-rise houses and apartments, it remains one man's fantasy of a skyscraper city, assembled lovingly with the detritus of both culture and nature.