14.4: The Human City- Spectacle, Memory, Desire

- Page ID

- 232350

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The "Felix" animated films exposed the complex human dimensions of urban modernity. His adventures also revealed the shifting nature of urban public space in the early twentieth century under the growing pressures of private, consumer-based forms of experience and leisure pursuits. The cinema offered a good example of this; occurring in the public space of the theater, its peculiar mode of address- in the dark, with the flickering lights and shadows of the moving image absorbing the watcher's full attention-lent itself to personal fantasy and the projection of purely private desires. Artists engaged with the human side of the city in a range of ways that embodied the intertwined nature of public and private worlds in the era of mass media.

The City as Spectacle: Reginald Marsh

From the late nineteenth century on, American artists had been fascinated by urban spectacle: the drama of the boxing ring, the circus, the popular theater, movie houses, vaudeville, and amusement parks that immersed the spectator in a world of light, color, sound, and movement. In the 1920s and 1930s, artists were particularly drawn to the parade of humanity across the stage of the city itself. Artists painting around Union Square in lower Manhattan focused repeatedly on the figure of the female shopper, and on the young working women who formed a growing percentage of the urban work force . For these so-called 14th Street School painters the new public presence of women in the city inspired ambivalent responses to the role of consumerism, advertising, and media culture more generally in shaping urban life.

Educated at Yale, Reginald Marsh (1898-1954) started out as an illustrator and cartoonist. His drawing skills served him well in capturing the energetic, pleasure seeking urban crowds he sought out on beaches, in Coney Island, in burlesque theaters and on the streets. Like others among the 14th Street School, Marsh extended the figurative concerns of early-twentieth-century Ashcan artists, bringing in addition a devotion to the Old Masters, inspired during a trip to Europe in 1925 by the multi-figural compositions of Rubens and Michelangelo. His interest in urban crowds frequently focused upon the figure of the voluptuous and sexualized female pursuing urban pleasures. What, asks scholar Ellen Todd, are we to make of this "hyper-glamorized working-class femininity," apparently removed from the realities of low wages and the dreary routines of the workaday world that preoccupied the Social Realists in these same years?25 Separated by class and social privilege from his subject matter, Marsh extended a tradition of urban voyeurism that began with such artists as John Sloan (see Chapter 12). His female figures-flamboyantly dressed and flaunting themselves to the viewer betray the artist's critical view, shared with others of his generation, regarding the impact of mass media on behavior. Women, the primary targets of advertising campaigns for everything from clothing to perfume, embodied fears about a loss of individuality under the homogenizing force of commercial media, driven by a desire to sell.

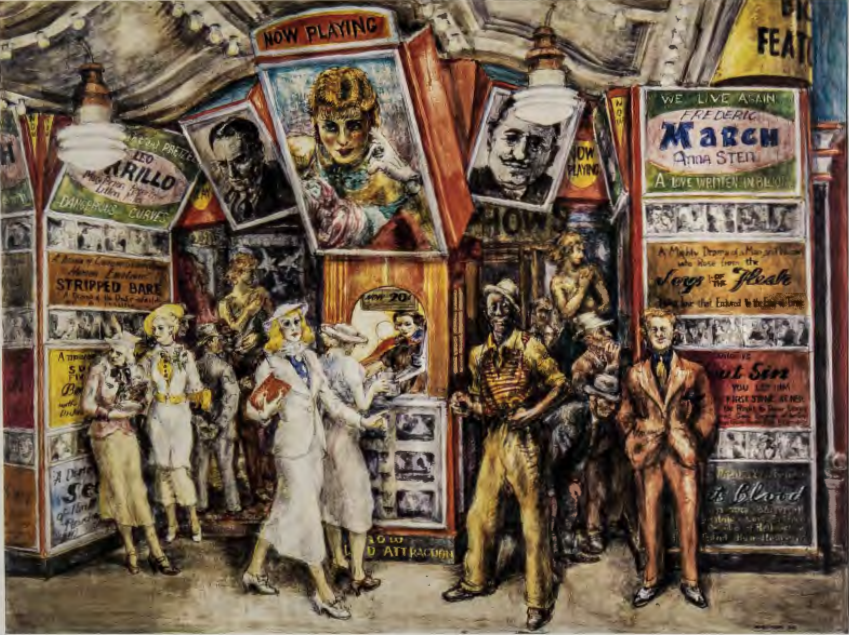

In Marsh's Twenty Cent Movie (fig. 14.28), the action occurs on a shallow, stage-like space that mimics the screen spectacles advertised throughout the painting on marquees and posters. In Marsh's world, "mass media" creates life in its own image. The movie theater is contained within the broader stage scenery of 42nd Street, like a set of Chinese boxes. Marsh's subject is a form of live street theater. His characters represent the motley mix of race, ethnicity, gender, and social group that increasingly occupied the public spaces of midtown Manhattan, from the confident, brazenly single working girl, to the short, dapper, redheaded fellow, hands in pockets, forever waiting for his next opportunity, to the lanky, good-natured black man who looks us rakishly in the eye. Provocative phrases-'Joys of the Flesh," "Sin," "Blood," "Stripped Bare"-and vampish women on movie posters grab our attention while flirting with our curiosity, mimicking the titillations of tabloid journalism, film, and advertising. Marsh's subject here is the urban spectacle of men and women looking at one another, their interests driven by a mix of sexual, social, and consuming appetites, fed by mass media. The three central actors return our gaze, implicating us in the street play. Two men intently study a bill in the theater lobby, while the two young women on the left peer expectantly out toward the street. In Twenty Cent Movie, Marsh explores how the consumption of urban commercial messages flowing from newspapers, films, advertising, billboards, and marquees was reshaping personal behavior. The term "attraction" (as in "coming attraction") links mass entertainment to the body and the senses, distancing modern urban existence even further from the ideal of self-discipline so important to maintaining social order in the older republic. By linking urban women so closely to advertising and consumption, Marsh promotes their objectification. Passive before the onslaught of commercial messages, his women embody deep-seated fears about the erosion of free will and the selfish feminine pursuit of gratification.

Quiet Absorption: Isabel Bishop's Women

Marsh's sirens differ pointedly from the young, delicately drawn female office workers of Isabel Bishop (1902-88). In their slightly rumpled ready-to-wear fashions and ordinary looks, these women turn toward one another, sharing a book or a meal, or speaking to one another across the interval of a male friend. This female world of affectionate companionship draws the viewer into an intimate exchange with them, which contrasts with the theatricality of other artists in the 14th Street School. In Bishop's Two Girls (fig. 14.29) gazes are focused inward, in response to the content of a letter that draws the two figures together. The shallow spaces mostly eliminate the urban environment in which they live out their workday lives. Two Girls was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1936, signaling the arrival of Bishop as an artist of note. Despite the charged emotion of the scene, it exudes a poised stillness far removed from the agitated energy of Marsh's street scenes. Bishop, like Marsh, was a careful student of the Old Masters, although her approach suggests Rembrandt rather than Rubens. A narrow color range, tight framing, and centered compositions pull us back from the spectacle of the urban commercial landscape into a more private sphere. For many years, Bishop kept a studio in Union Square, asking the working women of the neighborhood to model for her, and studying them at close range. Like Marsh, she was distanced from her working-class subjects by a privileged background, but her method of painting worked against the objectifying gaze of Marsh. Bishop's women comfortably occupy their environment while suggesting a subtle vitality, conveyed through her brushwork, which weaves together figure and ground. Bishop expresses her own need to paint people who seemed real to her, fully realized as subjects rather than as performers on a stage. Her women, passing between work and marriage, signal the promise of social mobility in the twentieth-century city. Individualized and anchored in their shallow spaces, their self-containment countervenes associations of women with mass culture, as well as with political mobilization.

The Emergence of Urban Black Culture

Historically a largely rural and southern population, black Americans relocated to northern cities beginning in the 1910s in one of the greatest demographic shifts in American history, known as the "Great Migration." The children of former slaves, they moved north in search of industrial jobs. With this shift a new urban identity began to take shape, fostering, in the era of Jim Crow, a new measure of social, cultural, and economic independence for a community shaped by a history of slavery, peonage, and poverty.

ARCHIBALD MOTLEY, JR. As the nation's largest black community, Harlem was the very type of the new black metropolis. Elsewhere in the great industrial cities of the North-Chicago in particular-vibrant black communities also took shape, characterized by black-owned businesses, churches, and nightclubs. Archibald Motley's Black Belt (fig. 14.30) is a panorama of the social habits and behavior of modern blacks in his home city of Chicago. After graduating from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1918, where he received solid if conservative academic training, Motley (1891-1981) embarked on a successful painting career which included sensitive portraits of mixed-race women and scenes of urban black entertainment. Motley was quite explicit about his desire to create an image of black culture for black audiences: he made them "part of my own work so they could see themselves as they are . . . I've always wanted to paint my people just the way they are."26 Though deeply committed to black subjects, he married a white woman and lived in a white neighborhood. Intent on creating a visual language that served his own sense of modern black life, he asked, "Why should the Negro painter, the Negro sculptor mimic that which the white man is doing, when he has such an enormous colossal field practically all his own?"27 In the 1920s he moved away from the naturalism that he felt characterized much black art of the time, and toward more volumetric, simplified, and stylized forms and rhythmically organized compositions. These qualities served what Motley called "the jazz aspects of the Negro" at a time when jazz music was entering its golden days of the 1920s.28 It helped shape a black urban identity. Originating as a slang word for sex, jazz continued to be a liberating force for middle-class Americans still struggling to free themselves from older conservative attitudes toward the body. Jazz was a hybrid, fusing European, African, and American musical elements, and traditional forms with modern urban innovations. It was itself the product of cultural migration.

Motley was granted a Guggenheim Fellowship to study in Paris in 1929, where he extended his fascination with the black metropolis to the expatriate Africans and West Indians congregating there, along with Americans of color, as part of an international black culture that developed in Paris in the decades between the wars. Black performers such as Josephine Baker and the jazz saxophonist Sidney Bechet had been drawn to Paris by a growing international enthusiasm for jazz, and by greater openness toward American black culture among sophisticated Parisians. Upon returning from Paris, Motley explored a cast of characters-from sleek light-skinned women and jazz babies to the street preachers, urban tricksters and card sharps, and romantic young couples-who came together to form a vibrantly varied social life. Drinking cocktails, preening their way through garden parties and barbecues, or dancing in jazz cabarets, they confidently laid claim-like Motley himself-to the privileges and possibilities of urban modernity, while remaining within the black community.

The Margins of the Modern: Edward Hopper and Charles Burchfield

"... This place / Is full, so full, of vacancy" -John Hollander. 29

The sleek profile of the skyscraper city was ubiquitous in America between the wars-in advertising, and in promotional symbols of progress. The immobility of Precisionism, with its iconography of heaven-surging towers, expressed a longing to lift the city above the haphazard and the randomly human, moving it from shadow to light. As a cultural icon, the skyscraper symbolized modernity's triumph over human limits, as well as transcendence of the body and of history itself. This "utopian" modernism banished waste areas from view, but these areas remained nonetheless zones of derelict buildings and derelict people, of discarded machinery, of pawnshops and vacant laundromats. Existing on the margins of a dynamic new order, these waste spaces held (and still hold) an important place in the imaginations of writers and artists questioning the costs of an economy and a culture relentlessly focused on money and glamor. They embody the blighting effects that a collective obsession with "success" produces. The discarded and the derelict possess a perennial appeal among those who have been scorched by too much exposure to modernity. The deserted streets of Edward Hopper and the lyrically melancholy images of Charles Burchfield cast their long shadow on the corporate rhetoric of engineered perfection and eternal youth holding sway over the nation's self-image.

EDWARD HOPPER. Edward Hopper (1882-1967)-an artist of monumental silence and stillness-is an odd figure in an urban culture of unremitting noisy movement. His images of urban desolation and solitude have shaped several generations of artists, writers, and filmmakers. His enigmatic art was the product of many influences. Along with training in Paris, and deep study of European art, he steeped himself throughout his lifetime in literature, theater, and Hollywood film- all narrative forms that influenced his approach to painting.

He has been called a realist. Yet Hopper's eerily empty rooms and streets, his mask-like faces, and charged intervals of space between people, suggest stories, and imply actions, occurring both before and after the scene represented. Their enigmatic narratives link them to the Magic Realism of the 1940s (see Chapter 17). Hopper's figures frequently seem to be listening to or looking at people or things beyond the frame of the painting in a way that recalls cinematic editing (shot and counter-shot). There is as well a sense of deja vu-things once seen and experienced but forgotten, returning to haunt the present.

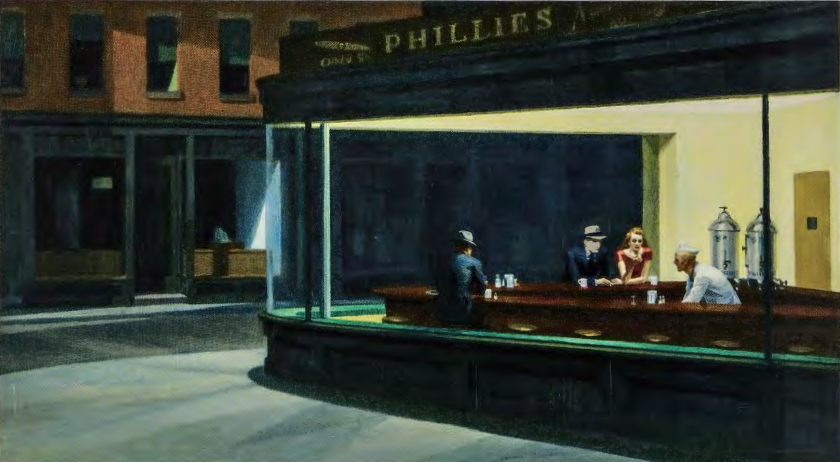

In the history of encounters between the fine arts and popular media, Hopper's art holds a place of honor, influenced by, and in turn influencing, the film culture from which he drew inspiration. The affinities between Hopper's art and film noir- a style of Hollywood film influenced by the migration of German expressionists such as Fritz Lang to Hollywood between the wars, and characterized by dark, psychologically charged settings-are especially close. In Nighthawks (fig. 14.31), with its sultry atmosphere, eerie copper-green shadows, and suggestion of narrative, the composition of the painting, and the placement of objects within it, tell us more than the expressionless figures themselves; the two stainless steel streamlined coffee urns seem to act out the suppressed physical tension between the man and woman sitting at the counter. Behind the scene, like a theatrical backdrop, is the anonymous urban architecture of storefronts and apartments, all dark, and apparently vacant.

Mass media was not only the inspiration but also the direct subject of Hopper's art. In his 1939 New York Movie (fig. 14.32), a statuesque usherette leans pensively against the wall, lost in her own world, while to the left an audience sits absorbed in the flickering images passing before them on the screen. Yet we do not see what they see; as is often the case, looking at a Hopper, one watches figures who are watching, without sharing their view. In New York Movie, the world of commercial media and the production of mass-consumed fantasies remain both irrelevant and inaccessible to the young woman and to us. Here Hopper explores the breach between the fantasy world of cinema, and the burden of boredom, isolation, and unrealized selfhood that remains for each dweller in the city to negotiate, mostly alone.

Hopper's paintings are populated by closed doors, tunnels, and blank windows that suggest an iconography of absence and failed efforts to find meaning. His interiors and city views are landscapes of urban exile from the plenitude of nature. In American art, nature was long the source of national identity and difference from Europe. In Hopper's art, it is blocked by houses and buildings, or forced to the margins of the composition, glimpsed out of a window, or in the form of dark, mysterious woods that hover beyond the well of light within which his figures act out their frozen sociability. Elsewhere nature appears as barren dunes, prairies, or treeless plains, drained of symbolic meaning.

Hopper's urban views are haunted by a sense of history. Corporate modernism produced a human subject who had no ties, who was unbound by the past, ready to experiment, to go forward into a future freed from the corrosions of time (for example, see fig. 17.33). Hopper's work returns us to a world that has been lost in the forward rush of technological modernization. His buildings have faces and histories; as novelist John Updike put it, "The architecture in Hopper acts, even when ... it is unpopulated and calm."30 Unlike the unpopulated landscapes of Precisionism, the urban and the human mirror one another, and carry the marks of time.

Despite his reputation as the visual poet of loneliness, Hopper was also drawn to the ways people set down roots against the odds, creating an awkward, sometimes homely sense of place out of placelessness. An old house sits beside railroad tracks-the symbol of mobility; the sculptural volumes of a lighthouse appear glistening white against a deep blue sky. His buildings carry the traces of the character and history that have been erased from the blank faces of his people. The built environment in Hopper becomes the living embodiment of culture, the material projection of a way of life. Yet Hopper-unlike other artists and writers searching for roots between the two world wars remained suspicious of an easily recovered "premodern" past. In its resistance to roots, his United States had always been modern. For anyone who has felt the poetry of emptiness, and the resistance of the American landscape to human habitation, Hopper's paintings evoke a paradoxical sense of place in the absence of roots.

CHARLES BURCHFIELD. Like Hopper, Charles Burchfield (1893-1967) was drawn to the poetry of dereliction, of a youthful culture gone prematurely aged. Burchfield's paintings in the years between the wars are a catalogue of tattered dreams: abandoned towns with their false-fronted ramshackle facades, sitting on the edge of vast prairies (fig. 14.33); decrepit Victorian rowhouses, resembling toothless old women; the barren wastes left by industries once robust, but which have moved on. Burchfield's ravaged countryside and shabby towns find their larger logic in the regionalist attack on the culture of the American pioneer. The years between the two world wars saw a broad reaction in the arts and letters against a commercial civilization that many traced back to the "slash and burn" mentality of westward expansion. For these critics, in place of community building and stewardship over nature, pioneers took what they needed and moved on, living only for the present, with no concern to create deeper ties to nature or history. In the unkempt and brittle quality of small towns Burchfield's vision echoes that of his friend the writer Sherwood Anderson, whose Winesburg, Ohio (1919) is a series of fictional sketches of small-town folk, rescued from insignificance through richly human stories otherwise untold. Burchfield's characters are buildings rather than people. These buildings resemble faces; his houses and streets are physiognomies of the lives lived within, expressing the passage of time and the imprint of history on the landscape. His cobwebbed, memory-haunted interiors reveal the dusky underside of the brash promotional rhetoric resounding through chambers of commerce around the country.

In Burchfield's gothic imagination, the past haunts the present. Yet he also found in the world of nature a source of re-enchantment. Throughout his career, in brilliant watercolors, he evoked the hidden life of nature's forms with visionary intensity- the inverse of a cultural landscape drained of energy.

The Dream-life of Popular Culture

Writing about Joseph Cornell, the biographer Deborah Solomon observed that "Nothing is more modern ... than a yearning for the past."31 Modernity sparked a reaction, which-in Cornell's case-took the form of objects recovered from intimate histories and salvaged from the ephemeral world of consumer culture by his act of collecting and preserving. Cornell holds a key place in a tradition of assemblage art that extends forward to the Beats in the 1950s and beyond. His work makes an instructive comparison with that of his contemporary Henry Darger, a visionary existing outside the art world. Cornell eventually achieved renown in the New York art scene, despite his odd and reclusive ways, whereas Darger lived a hermit-like life in a cramped studio apartment in Chicago, and only after his death was his work discovered.

JOSEPH CORNELL. Like Hopper, whose work he admired, Joseph Cornell (1903-72) was an urban fantasist. He sought to memorialize the fleeting life of the past, to give permanence to the transitory beauty he found in the city. Cornell's work was assembled from the already made; he transformed a modernist tradition of found objects through a highly personal landscape of associations and memories. He first started inserting these found objects into boxed constructions in the 1930s-years dominated by painters of the American scene working in a realist mode. Yet that decade also witnessed the introduction of Surrealism to the art culture of the United States through the Julien Levy Gallery and a related exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1931. Exposure to Surrealism freed Cornell's imagination. Working in the basement studio of a small house on Utopia Parkway in Flushing, Long Island, where he lived all his adult life, he meticulously constructed collages and wooden boxes contammg worlds-sometimes galaxies- in minature, collections of apparently unrelated objects poetically transformed by being placed alongside other objects to create new meanings. Rambling through New York City thrift shops, Cornell collected nineteenth-century engravings, biographies of people mostly forgotten, photographs, shells, bells, feathers, dolls, and cheap mass-produced and easily discarded objects from the dime store, such as the glass goblet that appears in many of his boxed constructions. Suggesting vast worlds of time and space, Cornell's intimately scaled boxes transform the banal, mass-produced products of commercial life into objects of wonder and poignant reminders of change and loss.

Cornell's relationship with American mass media was highly conflicted. What he referred to as "this age of endless dull pictures and endlessly dull movie personalities, of an incredible mediocrity and banality"32 could also become the raw material of new art forms. Cornell's gentle obsessions transformed his source material. In Untitled (Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall) (fig. 14.34), a celebrity icon is transported into Cornell's dreamworld- a box 3½ inches deep and fitted with a series of interior ramps of glass, glimpsed through five "portholes." A wooden ball, released through a trapdoor at the top, would travel down the ramps in a continuous motion. At the center of the box is a large photograph of Lauren Bacall, regarding us with a sultry gaze. A Hollywood sensation in the 1940s, Bacall (b. 1924) appears as a young girl in two smaller photographs, alternating with snapshots of her cocker spaniel Droopy and with later publicity stills. The sequence of images of the screen idol shuttles us between past and present, and redeems the worldly young actress through association with childhood innocence. Bacall's image in turn is juxtaposed with gleaming white skyscrapers soaring above street-level chaos and impurity, including the Chrysler Building, another "icon," like Bacall herself. Juxtaposing private family photographs, publicity shots, and iconic urban images, Cornell collapses the boundaries between public and private, past and present. Ultimately Penny Arcade realizes the power of private imagination to fuse the separate "compartments" of our lives.

Penny Arcade recalls the origins of cinema in early twentieth-century American cities. The window-like box frame around Bacall's face both transforms her into a work of art and recalls the peep-show effects that excited the voyeurism of early cinema audiences. Only here, the subject of our desire looks back at us. The staccato arrangement of photographs of the star recalls the flickering rhythms of early film projection. The blue tonality of the work also resembles early cinema. The immobility of the still image vies with the motion of the pinball as it travels down the internal ramps. Stopping and starting time, Penny Arcade explores the curious double life of mass media, the ephemerality of which- linked to mortality-paradoxically produces timeless icons. Penny Arcade inspires a shrine-like meditative engagement with the image of a mysterious and beautiful woman. Popular cinema- in the hands of Cornell-becomes an imaginary journey, saved from the banality of its mechanical means and its manufactured illusions.

HENRY DARGER. While Cornell stood at the edge of the New York art scene, and made nervous forays into it, Henry Darger's (1892- 1973) art world was resolutely private -revealed only after his death. He shared with Cornell a love of popular culture, though for the most part it was the pop culture of his youth, rather than his adulthood. And, as with Cornell, change and loss were the underpinnings of his work. Three years after Darger was born, his mother died in childbirth, and he spent much of his childhood in an orphanage, later being sent to a state-run asylum for "feebleminded" children. At the age of about eighteen, shortly after his return to city life in Chicago, Darger began the epic fantasy that would absorb him for more than sixty years: The Realms of the Unreal, consisting of over 15,000 manuscript pages and several hundred illustrations centering on "The Vivian Girls," an imaginary corps of seven brave little girls who battle against their foes, the Glandelinians, who have enslaved them.

Darger held a job as a janitor and dishwasher at a hospital, went to church daily, but rarely socialized with others, preferring his fantasy world. He obsessively collected coloring books, advertising circulars, and magazines, in search of images he could adapt for his work. While Cornell's collecting mania extended to all sorts of three dimensional ephemera, toys, and games, Darger's work was resolutely two-dimensional. He sometimes collaged these found images into his paintings. More often he traced or copied photos and drawings of little girls. He sometimes glued pieces of paper together to make panels as large as nine feet long for his epic panoramas.

Rather than focusing on contemporary popular culture such as movie stars and skyscrapers, Darger seems to have become stuck in the classic popular literature of his early childhood, including L. Frank Baum's The Wizard of Oz books, Charles Dickens's novels, and Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. He adapted themes from these books into his own illustrated novel with its distinctive iconography. His imagery focuses on children, both naked and clothed, in scenes ranging from carefree garden and domestic settings to warfare, horseback riding, and sword fighting. Some of the nude children are sexually ambiguous, or have male genitals. In some illustrations, the children are being hung, crucified, or mutilated. In the work illustrated here (fig. 14.35), the Vivian Girls and their cohorts are at peace in a scene of Christian redemption. Darger was a devout Catholic; here, the Sacred Heart of Jesus (rendered with almost clinical precision) is the focal point of the scene.

While some viewers find his obsession with little girls pathological and sinister, it seems clear that he identified with the tribulations of these brave pre-pubescent children. He himself had been a powerless (and possibly abused) child, held in the clutches of an early-twentieth-century mental health system that did little more than warehouse disturbed children. Darger writes in his narrative about the horrors of child slavery, and celebrates the bravery of his beloved Vivian Girls: "In these countries I write about, girls and boys fear nothing, not even dangerous snakes, vicious rats or mice, deadly insects, nor anything because they do not have wickedness in their characters."33

When Darger died, his landlord found his tiny Chicago apartment crammed with huge notebooks of typed narrative, collages, pictures of little girls, and a wealth of unused collage materials. The landlord, Nathan Lerner-a designer and photographer-recognized the artistic significance of this motley collection. Only after his death was Darger's secret fantasy world recognized as one of the great imaginative works of twentieth-century art.