6.2: Art of the People

- Page ID

- 232307

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)When we speak of "sentimental culture," we are describing a society in which the values of the home-and the worlds of women and children within it-come to define public expectations and behavior. Both inside and outside the home, complex social webs link women and men to their families, to their communities, and to each other. Many forms of art and many kinds of objects were produced by people who did not necessarily think of themselves as artists but who cared deeply about the shape and look of things.

Quilts and Women's Culture, 1800-60

In 1826, fourteen-year-old Sarah Johnson (1812-76), of eastern Pennsylvania, made her fourth quilt (fig. 6.11). Its central medallion was made of hundreds of bits of fabric composed into a complex design. Radiating out from this is a repeating geometric pattern of blocks of colored eight pointed stars, alternating with plain white squares. The geometric shapes and colors appear to stand out against the white, which then functions as a background. Sarah Johnson has surrounded her quilt with a border of pieced triangles in a pattern known as "flying geese." The triangles, in turn, are bordered by bands of orange and pink, which enclose the whole design. This quilt demonstrates the way that nineteenth-century women transformed quilting into an endlessly fascinating- and often abstract-play of geometric shapes.

Johnson's quilt is composed of more than four thousand individual pieces of fabric. Some may have been scraps left over from dressmaking, though certainly the white, pink, and orange (as well as the fabric for the backing) would have been purchased specifically for this project.

It would not have been uncommon in the nineteenth century for a fourteen-year old girl to have completed as many as fo ur quilts. Little girls mastered simple hand-sewing techniques by the age of four or five , and soon became proficient needlewomen, as numerous eighteenth- and nineteenth-century samplers demonstrate (see Chapter 5). In the colonial economy, such skills were a practical necessity, for all members, even the youngest, contributed to the household through hard work. By the 1820s, however, with a growing middle class, women's skills were directed more to "fancy work," such as this quilt, than to the plain work of mending or sewing for necessity.

The patchwork quilt has served-throughout the twentieth century and today-as a metaphor for all that people value about the American character. As such, the quilt has accrued many myths regarding its history. Erroneously described as anonymous works made of scraps and leftovers, quilts seem to be symbols of a typically American ingenuity. They are associated with the triumph of artistic vision over adversity and celebrate women's thrift and industry-a collective sort of "making-do."

In fact, however, the large majority of American quilts were not made of scraps. They were deliberate artistic statements made from whole cloth, which was cut up and reassembled in a painstaking and purposeful way to produce elegant optical patterns. Most were not intended to be anonymous. In fact, many boldly incorporate the artist's name in the imagery. Few were collectively made or designed, though women may have helped each other with the finishing work after the quilt top had been pieced.

In many early-nineteenth-century homes (and persisting later in rural areas), quilts were among the most treasured objects owned by a family. We know how much women valued the work of their needles by the fact that quilts are prominently mentioned in nineteenth-century wills. Thousands of them have been preserved, sometimes unused and unwashed, from every decade from 1800 to the present-a demonstration of how they were prized as works of art.

The earliest American quilts seem to have been made of large pieces of whole cloth, then normally wool or linen, stitched together to form a "sandwich" (quilt top, inner layer, and backing). The surface of this wool or linen blanket would then be covered by a subtle layer of imagery laboriously formed by hand, using needle and thread to work patterns of vines, flowers, or geometric designs. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, imported cloth was expensive, and except among the wealthiest people, was usually combined with local handspun cloth.

Early-nineteenth-century quilts look very much like their European counterparts, usually featuring some combination of piecework and applique. ("Piecework," also called "patchwork," is the sewing together of small pieces of cloth into geometric patterns, while "applique" is the stitching of one fabric shape or motif onto another.) Often such quilts incorporate pieces of British or (Asian) Indian chintz (a glazed cotton cloth printed with lush, multicolored floral patterns). Chintz was prized as a mark of wealth and status.

The large-scale manufacture of printed fabrics began in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states during the first decades of the nineteenth century, advanced largely by immigrants who were expert in English roller-printing methods. By 1835, the mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, alone turned out more than 750,000 yards of cotton fabric per week-an output that would vastly increase after the Civil War. The growing profusion of printed cottons in American quilts is one measure of the advance of the Industrial Revolution in the United States.

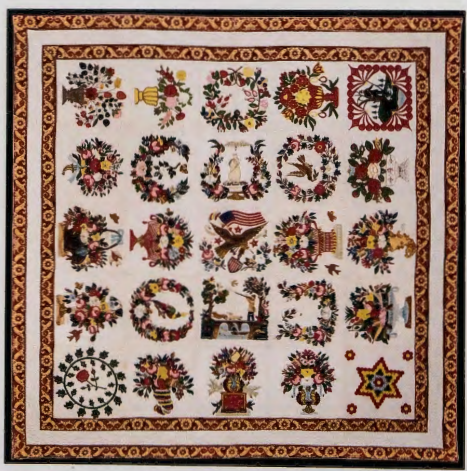

BALTIMORE ALBUM QUILTS. In the middle of the nineteenth century, few professional avenues, other than sewing and teaching, were open to women who needed to support themselves and their families. While some women earned money piecing and quilting for others, there is evidence of at least one enterprising woman who parlayed her skills into a business, in which she prepared quilt blocks for other women to sew and to present as their own achievements.

Born in Bavaria in 1810, Mary Heidenroder Simon arrived in Baltimore in 1844, at the start of a new local fad in quilt making, which was characterized by remarkably ambitious applique patterns. The Baltimore Album quilt, as it came to be called, made use of the abundance of fine cottons available in that city (fig. 6.12). Baltimore was then the nation's largest seaport. Its prosperity was built on imported textiles, as well as the calico fabric milled there from cotton grown on southern plantations. As a mother at home with babies, Mary Simon bought fine fabrics, and cut and basted them onto white cotton in ambitious pictorial designs of her own devising, which she then sold as kits to more affluent women.

Many of Mary Simon's blocks were incorporated into quilts finished by others and exhibited as their own work. As a working-class immigrant, she did not socialize with prosperous ladies, who sewed at home as an avocation. But her ingenuity allowed their less innovative needlework skills to shine; their names were inked on each block when they gave the finished quilt to a friend on her wedding day. The quilt, then, became not only a pictorial album of lush garlands, flower baskets, and cornucopias, but an album of friendship, too-a large-scale, colorful version of the tiny autograph albums that were also popular in that era.

FRIENDSHIP QUILTS. During the antebellum period, many American women were joining hands to make more modest Friendship quilts. A group of women would make identical piecework blocks, often out of scrap fabrics, usually with a central block of plain white or cream-colored muslin. The use of scraps in nineteenth-century Friendship quilts probably gave rise to the erroneous assumption that all quilts were collective art works made of scraps. Midnineteenth-century advances in steel pen nibs and indelible writing inks (inks made without iron, which would disintegrate fabric) made it easier to write on cloth. Women inscribed their names, dates, and sentimental verses on the plain cloth in the center of the patchwork blocks, as in the nine-patch design illustrated here (fig. 6.13). Fine hand quilting is not a hallmark of Friendship quilts; they seldom have the exquisite stitchery seen on Baltimore Album quilts, for example. They were keepsakes of female friendship and, ironically, are sometimes the only place where a woman's name is preserved through the generations; in the mid-1800s, the government census listed only the name of the "head of the household," usually male.

Friendship quilts were often given as engagement presents or going-away presents. During the era when such quilts were most popular (1840-60), tens of thousands of women made the journey to a new life in the West. A huge exodus of people from towns and farms in New England, New York, Ohio, and Kentucky set out on the Oregon Trail, the main westward route. By 1860, some three-hundred thousand American "overlanders" had made the trek. When embarking upon the westward journey, people rightly assumed that they might never see their loved ones again. Many were given Friendship quilts as an enduring sign of affection. Literally blanketed by her friends, a pioneer woman felt fortified for the perilous journey upon which she was embarking. Moreover, in the new communities formed on the trail, and in the West, women's arts were a means of bonding with other women. Quilt block patterns and fabrics could be exchanged, and pieced tops could be quilted together. The cheerful Friendship quilt illustrated in figure 6.13 was inscribed "From M. A. Knowles to her Sweet Sister Emma, 1843." Other friends and church members signed the quilt, too- one with the motto "A faithful friend is the medicine of life." Martha Ann Knowles (1814- 98) made this quilt for her younger sister several years before Emma's marriage to a minister, perhaps as a gift for Emma's hope chest.

While few, if any, quilts hung on museum walls in the nineteenth century, many were offered for public viewing at fund-raising events in the 1830s- 1860s and especially at the numerous county and state fairs (and later world's fairs), where prizes were given for quilts. Women flocked to these public events, just as painters and sculptors looked to exhibitions held at academies, salons, and museums. Many more people visited quilt exhibitions at county and state fairs in the nineteenth century than visited museums- hundreds of thousands would attend a large fair such as the Ohio State Fair. Quilt making was a democratic art, which crossed boundaries of class and ethnicity.

RAISING FUNDS AND SOCIAL AWARENESS. Nineteenth century American women made quilts to raise money and to enlighten their peers on behalf of the social causes they supported. In many cities, they formed "ladies' benevolent sewing societies" to make quilts and other goods needed by missionaries. Some of these groups ardently supported social reform: some were antislavery, while the others set the stage for the temperance and the women's suffrage movements.

Quilts and other handmade goods were displayed and sold at antislavery fairs, held in Boston starting in 1834 and in other cities thereafter. Women raised thousands of dollars for the antislavery cause. Small cases for sewing needles were emblazoned with abolitionist Sarah Grimke's famous cry, "May the point of our needles prick the slave owner's conscience."2

During the Civil War, northern women organized U. S. Sanitary Commission fairs (an early version of today's Red Cross). Halls lavishly festooned with quilts and American flags were opened to the public. By selling their needlework and other goods, women raised money and sent medical supplies (including handmade bandages, and quilts to cover the soldiers' infirmary beds) to the battlefields. Northern women raised more than $4,500,000 through such fairs. At one fair in Iowa in 1864, women raised $50,000 through the sale of their quilts in just eight days. Abraham Lincoln himself praised the industry of American women:

Nothing has been more remarkable than these fairs, for the relief of suffering soldiers and their families. And the chief agents in these fairs are the women of America. . . I have never studied the art of paying compliments to women; but I must say that if all that has been said by orators and poets since the creation of the world in praise of women were applied to the women of America, it would not do them justice for their conduct during this war. 3

The same principle expressed in Friendship quilts was often used in fund-raising quilts. Women would solicit donations of 5 cents or rn cents to inscribe the name of the subscriber on a strip of cloth to be incorporated into a quilt. The quilt would then be sold, and both subscription money and sale price donated to the cause.

Folk and Vernacular Traditions

For almost a century, scholars and collectors have sought to define folk art. The more everyone tries, the more slippery the notion becomes. In 1950, after more than three decades of intensive collecting of folk art, experts confidently listed the following as among the range of adjectives to describe folk art: unselfconscious, naive, unsophisticated, provincial, rural, dynamic, romantic, isolated, untroubled by lack of skill. One scholar proclaimed, "Folk art is child art on an adult level," while another observed that it was made by "simple people who live in a static society." Today we sense that these definitions tend to reveal more about society's preconceptions and blind spots than they do about the art or artists under examination.

Historically, folk art has been seen as a product of regional or ethnic traditions. Examples include Shaker furniture, Pennsylvania German (or "Dutch," a corruption of "Deutsch," or German) fraktur, or New Mexican santero carving. Sometimes folk artists work in rural communities, far from the urban centers where artistic standards are dictated. Sometimes folk art parallels academic art; in other instances it diverges from academic trends.

Many scholars now prefer the term vernacular traditions, a term that means "local" or "everyday" traditions. "Vernacular" refers not only to the handmade but also to popular, mass-produced items such as commercial posters and billboards. Some prefer the term self taught, but that is not accurate in relation to many folk traditions, in which standards and skills are carefully transmitted within families and communities, or through apprenticeship.

RURAL PAINTERS. Itinerant artists traveled from farm to farm throughout rural America, bringing with them the commercial revolution that had already transformed life in the nation's towns and cities. Attuned to the hunger of those around them for fashionable consumer items, they responded to what the scholar David Jaffe has termed the "commercialization" of the countryside by pioneering low-cost, high-volume portraiture. These "artisan entrepreneurs" often began as painters of signs, carriages, sleighs, or houses and turned to portrait painting as the demand for the amenities of middle-class life expanded. They provided black and white silhouettes for those without much money; they added color for an extra fee; and, at the high end, they offered painted portraits distinguished by bold lines, bright colors, and decorative surfaces. With a far-flung clientele, country painters could standardize their portraits while still satisfying their customers. They made use of stencils and stylized forms- modes of painting that speeded the process along-while simultaneously individualizing their portraits by adding their sitters' distinctive possessions. They thus allowed their country sitters to show off their wealth and social status while minimizing the time required to complete each painting.

Rufus Porter (1792- 1884), for example, began his career as a house and sign painter in Portland, Maine. He soon took to the road, using a camera obscura-a box with a lens and mirror-to cast the sitter's image onto a sheet of paper, trace the image, and then sell the "correct likeness" for 20 cents. He could produce as many as 20 profiles an evening (fig. 6.14). Itinerant artists such as Porter helped satisfy the demand for consumer goods-and especially for objects of "culture"-that swept rural America into the accelerating commercial revolution during the early and middle decades of the nineteenth century.

One of the most prolific-and distinctive-of these vernacular painters was Ammi Phillips (1788- 1865), whose fifty-year career in New York and New England resulted in an extraordinary legacy of images of the rural middle class. Like other country painters, Phillips developed a set of conventions, props, and styles, which he could vary from sitter to sitter while still producing a recognizable likeness of each subject. Phillips's portrait of Jane Ann Campbell (c. 1820) includes red drapery at the edge of the painting, which appears again and again in works of his early career (fig. 6.15). The three-quarters profile allowed him to paint only one ear, a trick repeated in the doll on Jane Campbell's lap. Although Jane Campbell was only three years old at the time Phillips painted her image, she appears, like her doll, to have the timeless features vernacular painters used to signify early childhood in general. Phillips has lavished attention on Jane's accessories: her patterned dress, embroidered hem and cuffs, lace ruff, and pearl necklace. The busy patterns of the carpet and footstool, by contrast, are painted broadly and lack the detailed attention that distinguishes Jane's clothing.

An irony of portraits such as Jane Ann Campbell is that they have been idealized as "folk art," naive reminders of a simpler, preindustrial world. In fact, they are one of the earliest forms of mass-produced imagery that we possess. Their stylization is a result of the painter's need to maximize productivity; their portrayal of objects and goods is a result of their sitters' desire to affirm their "arrival" as members of the middle class; and their "naivete" is calculated, a result of economic efficiency.

SILHOUETTES. Silhouettes were the most common portraits in the first half of the nineteenth century. Popular in both urban and rural America, these intimate, delicate shadow portraits preserved the outlines of the sitter's profile in ink or cut paper. There were various techniques for producing them; some artists made freehand tracings of the shadows cast by subjects sitting in front of candles or lamps, while others, such as Rufus Porter, adapted optical devices such as the camera obscura.

The physiognotrace was invented specifically for the mechanical production of silhouettes. Using this device, the artist skimmed a dowel along the contours of the sitter's head. The dowel was connected to a stylus, which automatically transferred the outline of the head onto an adjacent sheet of folded paper. Using scissors or a blade, the artist would then carefully cut along the outline; because the paper had been twice folded, this process automatically yielded four copies of the silhouette. Introduced to America around the turn of the nineteenth century, the physiognotrace was a popular concession at Charles Willson Peale's Museum in Philadelphia (see Chapter 5), where Moses Williams, a former slave of the Peale family, made his living operating the machine and cutting the portraits. During the early years of the nineteenth century, Williams made as many as eight thousand portraits a year in the museum at a cost of 8 cents per sitter. The physiognotrace image of Williams shown here (fig. 6.16) may be a self-portrait.

While the production of silhouettes was, compared to oil portraiture, relatively simple, the cultural meanings of the resulting images were complex. Like the photographs that would eventually supersede them, silhouettes featured patterns of light and shade automatically produced by the sitter. They were thus seen as an unimpeachably direct and accurate form of representation. As the art historian Wendy Bellion has shown, this mantle of "true representation" gave silhouettes a special meaning in the early republic, when American society was consumed by broad-ranging debates about appearance and deception in politics and daily life.

Silhouettes were also associated with classical virtues. The profile format not only recalled images on ancient coins and medals but also figured in a well-known ancient account of the origin of visual representation. In Pliny the Eider's Natural History (77 c.E.) a Corinthian maiden, whose lover is about to depart for war, traces the outline of his profile on the wall and thereby invents the art of painting. Pliny's tale added further nuance to the cultural meaning of the silhouette; along with its suggestions of the true and direct presence of the sitter, the silhouette thus also carried sentimental connotations of separation and mourning. This rich dual significance is echoed in the structure of all silhouettes. The detailed outline preserves the unique physical presence of the sitter, but the dark, blank shape simultaneously suggests absence and loss.

"JUST FOR PRETTY." Throughout the history of the United States, people who do not necessarily consider themselves artists have created a huge number of unique objects of great wit, aesthetic pleasure, and eloquence. The German speaking people who settled Pennsylvania and other mid-Atlantic states in the nineteenth century have a special phrase for such art: Yuscht fer schnee (just for pretty). They mean by this phrase art that gives pleasure to its viewers purely through its decorative effect.

Mary Ann Willson, for example, who lived on the western frontier of New York State in the early decades of the nineteenth century, produced numerous watercolors distinguished by their love for decorative play. Willson's "Marimaid" (mermaid) is a wonderfully cheerful figure, with her bulging lower body of bright, overlapping scales, each one elaborated with dots, dashes, circles, or hatch marks (fig. 6.17). Willson created religious scenes, portraits, birds, and flowers, adapting images she found in prints to her own vision. A nineteenth-century tourist book of the region notes that Willson sold her work "from Canada to Mobile." Her career suggests how folk art operates within a larger market culture. Even without academic training, numerous folk artists managed, through enterprise, to earn a living from their art.

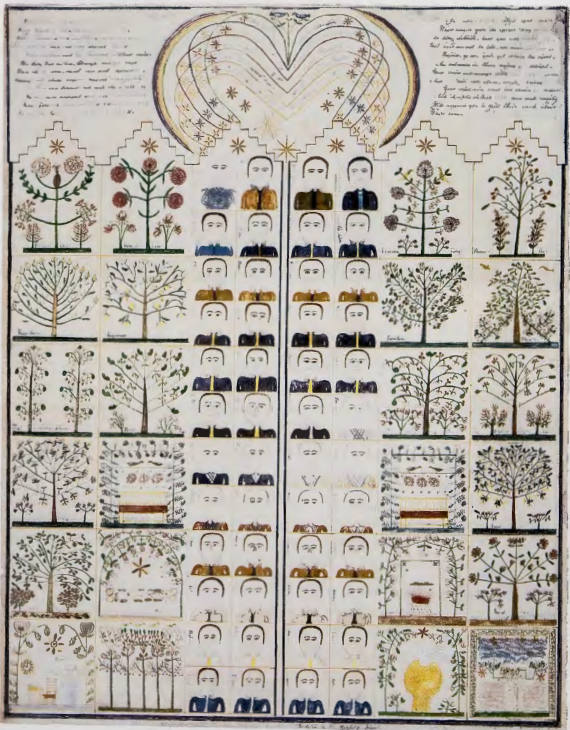

FRAKTUR. Sometimes the decorative qualities of vernacular art go hand in hand with a more practical purpose, like keeping family records. Many Germans who immigrated to Pennsylvania practiced a calligraphy called fraktur schriften, a phrase for the stylized or "fractured" writing on medieval religious manuscripts. Fraktur was created by specialists and amateurs, both male and female. In the late eighteenth and the nineteenth century, many birth certificates and baptismal records (as well as prayers, Bible verses, and moral sayings) were inscribed in this decorative format, often accompanied by painted scenes of hearts, flowers, birds, and people. These works of art could serve as legal documents submitted to prove age and citizenship, but mostly they were made in loving celebration of important family events. Around 1810, Friedrich Bandel made a family record (fig. 6.18). Within the heart on the left is recorded in German the birth of George Manger to Henrich and Elizabeth Manger on June 6, 1809. Above are representations of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. In small blocks between the hearts are recorded the words "love," "faith," "hope," "humility," "patience," among other virtues. Later in the nineteenth century, professionally printed death certificates replaced the hand-drawn fraktur for recording family history.

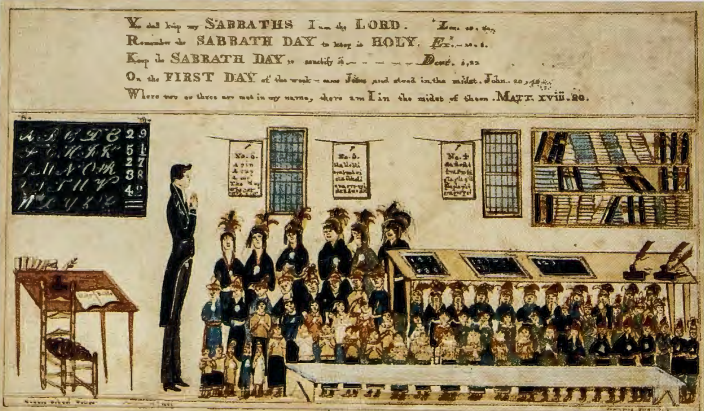

NATIVE IMAGERY IN VERNACULAR ART. Images of Indians were common in the vernacular art of the nineteenth century. Dennis Cusick (1799-c. 1822) created watercolors that combined his love for detail and surface play with a vision of Native American identity. Cusick, a Tuscarora Indian ( one of the member tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy), was active in the Congregationalist Mission School on the Seneca Reservation, near Buffalo, New York (fig. 6.19). Although Native, _his family was Christian and acculturated, and his father had served as a lieutenant in the American army during the Revolutionary War.

In Keep the Sabbath, Cusick depicts more than five dozen students and the details of their classroom on a surface smaller than 5 inches by 8 inches The students stand in prayer, led by their teacher. By depicting them in the Native dress of the period, Cusick is intent on showing that despite religious conversion, they have not forsaken Iroquois identity. The boys wear the gustoweh, elaborate traditional plumed headgear. The artist depicts books on the shelves, writing charts on the walls, slates (for practicing letters) on the table, and the open Bible on the teacher's desk. James Young, the teacher pictured here, noted that Cusick was self-taught, probably from copying prints and engravings. In one of his works (painted on a box in which white Americans deposited contributions to the mission school) he expressed his vision of Native acculturation: "My friend, You see I am not white like you; I am Red-but my heart is in the same place with your heart; my blood is the same colour as your blood; my limbs are like your limbs. I am an AMERICAN." 4

Perhaps the most familiar image of Native Americans in the nineteenth century stemmed from the cigar-store Indian, a figure that often stood as a large three-dimensional advertisement outside of tobacconist shops. Indians were linked in the popular imagination to tobacco, a distinctly New World crop. Both male and female Indian figures served as cigar-store advertisements, often with rolls of cigars in their hands or sheaves of tobacco as part of their adornment.

Chief Black Hawk (fig. 6.20) is a regal figure, standing nearly 7 feet tall. The art historian Ralph Sessions has observed that this is not, in fact, a portrait of the famous Sauk chief named Black Hawk (1767-1838), who lived in the Great Lakes region and led his people in the so-called Black Hawk War of 1832. Instead, Black Hawk (c. 1848-55) is an idealized portrait of a stoic Indian. Merging neoclassical and Native stereotypes, his pose and toga-like costume recall ancient statues of Roman senators, while his animal pelt and scalp lock place him as a Native American of colonial times. Together these attributes form a third stereotype-that of the "Noble Savage" (see Chapter 2). Black Hawk stood in front of a cigar store in Louisville, Kentucky, during the second half of the nineteenth century.

"Saint Tammany" (fig. 6.21) was a semi-mythic figure deriving from a renowned Delaware chief named Tamanend, who, with William Penn, forged many treaties of the 1680s and 1690s. These treaties insured more than seventy years of peace between the relatively un-warlik.e Delaware and the pacifist Quakers and Mennonites who were populating eastern Pennsylvania. The legendary stature of this chief led people to begin to call him "King Tammany"; by the end of the eighteenth century he had become "Saint Tammany," a figure invoked in public spectacle, such as May Day celebrations, which often involve creative mischief by Anglo-American men garbed as Indians. In Pennsylvania, the Saint Tammany Society was an anti-British organization dating from before the American Revolution. After the Revolution, Saint Tammany became the patron of men's patriotic fraternal societies, especially in Pennsylvania and New York. The Saint Tammany weathervane illustrated here stood atop the headquarters of one such club.

As the historian Philip Deloria has demonstrated, Tammany allowed for the creation of a new identity for American patriots-one that drew from both aboriginal and European traditions. Just as art changes radically over time, so do symbols. In American history, Tammany is best remembered as the name of a powerful and corrupt political organization that ruled New York City politics through much of the nineteenth century. Yet the political machine never totally lost its connection with Indian symbolism, however tenuous: its headquarters, an imposing building, was known as the Tammany Hall "Wigwam."

Shaker Art and Innovation

The Shakers were among the most innovative religious groups to flourish in the United States. Though never numerous- they had no more than six thousand adherents at their high point in the first half of the nineteenth century- their legacy in American design and technology endures. They called themselves "the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing," but were more popularly known as the Shakers (from "Shaking Quakers") because of their ecstatic dancing as a form of prayer. The founder of the sect, Ann Lee, came to America from England in 1774. Within several decades there were Shaker communities in a huge area spreading from New England to Kentucky. Shakers didn't believe in slavery, private property, or male dominance. They were celibate, increasing their numbers by conversion and by taking in orphans. Mother Ann Lee exhorted early believers to "put their hands to work and hearts to God." Out of this simple dictum came some of the finest and best-loved innovations in household design and technology of the nineteenth century.

Shakers earned money by selling their produce, furniture, and implements to outsiders. A Shaker product was known for its good quality- from the seeds they sold in packets (they were the first to do so) and the medicinal herbs and remedies they marketed, to the boxes and chairs they sold in quantity.

Unlike the Amish and other religious sects who spurn modern advances in technology, nineteenth-century Shakers welcomed technological advancement. For example, around 1800, Theodore Bates, a Shaker from Watervliet, New York, developed the flat broom of the type still used today- a significant improvement on the unwieldy round brooms then generally used. Ten years later, Tabitha Babbitt, a Shaker from Massachusetts , invented an early version of the circular saw. Shakers have also been credited with the clothespin, and with many refinements in farm tools, woodworking tools, baking ovens, and washing machines, but their innovations are hard to document because most Shakers did not believe in the concept of patents.

Shaker design was motivated by utility, not aesthetic consideration. Usefulness was paramount-both in one's life and in the fruits of one's labors; "superfluities" must be avoided. Shaker laws, set down in 1821, dictated, "Fancy articles of any kind, or articles which are superfluously finished, trimmed, or ornamented, are not suitable for Believers, and may not be used or purchased." Indeed, one nineteenth-century elder proclaimed, "The beautiful is absurd and abnormal. It has no business with us."

SHAKER BOX. The Shaker oval box is a good example of their ethic (fig. 6.22). The sides, or walls, of the boxes and their lids are sheets of maple split from a plank. These strips (some as thin as 1/32 inch) bend easily when soaked or steamed. They are wrapped around an oval mold and fastened shut with copper tacks through their swallowtail joints. Durable pine boards are used for the flat tops and bases.

Shakers did not invent this box form; but as with everything they made, they pared it down to the simplest shape and the finest craftsmanship. An industrious Shaker woodworker might make three or four dozen of his box walls in a day, in a system of mass production in which many walls were made at once, and then many lids. Shaker boxes were often sold in multiples of graduated sizes. They held dry foodstuffs, sewing implements, and other personal effects, and were marketed to non-Shakers as well as to each other. Although some people imagine Shakers as historical and unchanging "folk artists," in fact, their works were part of the "consumer revolution."

SHAKER FURNITURE. Shaker chairs, in production since about 1790, take the idea of the eighteenth-century New England ladder-back chair and refine it (fig. 6.23). The Shaker chair is more slender and lightweight than a traditional ladder-back chair. It lacks ornamentation on the lathe-turned posts, except for a simple, graceful finial at the top. Often the legs are tilted, so that the chair angles slightly backward, rather than being stiffly-and uncomfortably upright. Some chairs incorporate wooden ball bearings on the bottom of the back legs, allowing the sitter to lean back without toppling over. Variants include armchairs, rocking chairs, and even wheelchairs. The seats were woven from cloth tape or natural cane. While today most Shaker reproductions (and most Shaker furniture in museum collections) are left the natural color of the wood, in the early nineteenth century Shakers often used yellow, red, or green pigments to paint their furniture (in a manner similar to the oval boxes). As with the manufacture of boxes, the Shaker chair industry was a robust business in the mid-nineteenth century.

SHAKER SPIRITUAL VISIONS. The Shakers also produced eloquent ink and watercolor drawings that recorded their spiritual visions. People who received heavenly visions were called "instruments," for they were seen as literally the tool by which a heavenly vision was transmitted to the community. Such human "instruments" often made drawings as gifts to other members of the community. Their visions were thought to be transmitted directly from Mother Ann Lee, their founder, who had died in 1784.

In An Emblem of the Heavenly Sphere, Polly Collins (1801-84), who lived in the Shaker community in Hancock, Massachusetts, depicted her vision of the layout of heaven (fig. 6.24). Rows of saints and prophets (including Mother Ann Lee) fill the center of the drawing, surrounded by the flowering trees of paradise. The verse at the upper left begins:

Here is an emblem of the world above

Where saints in order, are combined in love;

Where thousands, and ten thousand souls as one

Can join the choir and sing around the Throne.

Many Shaker drawings were inscribed as if Mother Ann Lee herself had drawn them-evidence that Shaker graphic artists considered themselves mere transmitters of a divine message, a gift from heaven. These drawings were made principally by young women during the 1840s and 1850s, a time of religious crisis in Shaker communities. Mother Ann Lee had been dead for some sixty years, and the younger generation had no direct experience of her charismatic ministry: The drawings were meant to affirm a close connection between Mother Ann and the living members of the community, and to keep her memory vivid. The religious laws of the Shakers stated, "No pictures or paintings shall ever be hung up in our dwelling rooms, shops, or Office." Instead, these "Gift Drawings" were examined on the lap, or on the floor, or kept in a cupboard for occasional viewing. In style and format such drawings recall other vernacular designs, including fraktur, needlework samplers, and wood and stone carvings. The frontal faces lined up in Polly Collins's drawing, for example, resemble the portraits carved on some New England gravestones (see Chapter 3). The artist may have come from a family of Vermont stone carvers, whose work influenced her own.