6.1: The Language of Emotion

- Page ID

- 232306

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)During the antebellum years, sentiment played a leading role in shaping American life. Sentimental culture extolled the virtues of honesty and simplicity. Its heroes were chaste women and selfless mothers, and it viewed childhood as an age of purity and innocence. Sentimental culture was also obsessed with death, partly because so many women died in childbirth and so many children failed to live to adulthood. Its highest virtue was self-sacrifice, the willingness to give one's life for others.

Home and Family

Historically, sentimentalism is tied to the separation of the workplace from the home. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a household might include servants, apprentices, boarders, and a family network of children, cousins, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. Going to work rarely required leaving home. But by the beginning of the nineteenth century, this older artisanal economy was giving way to industrialization: the clustering of workers in work spaces outside the home; the organization of work into separate, repetitive tasks; the substitution of cheap labor for skilled labor; and the rise of a managerial class to oversee this less-skilled workforce.

The household changed, too. It ceased to be the central economic unit of society. Among the middle classes especially in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states- the middle-class home became a "haven in a heartless world." Women's work was associated with childrearing and emotional nurture. Women provided men with emotional support to face the workplace anew each day, and they educated their children into their role as future citizens. To accomplish this, women were expected to be paragons of virtue and self-sacrifice. They were placed on a pedestal and honored for their purity and selflessness. Their labor seemed invisible, recognized for its emotional worth rather than its economic value. Home and family, in turn, came to be viewed in opposition to the world of work. The result was a new notion of domesticity.

LILLY MARTIN SPENCER. In painting, sentimentalism is exemplified by the work of Lilly Martin Spencer (1822-1902), who specialized in images of middle-class domestic life. Spencer was one of the few successful female artists of the antebellum period and one of the only women invited to join the prestigious National Academy of Design, in New York, the dominant organization of professional artists throughout the nineteenth century. Spencer's membership, however, did not include voting rights. Her Domestic Happiness (1849) (fig. 6.1) shows a glowing couple watching their two children sleep. A light shines beatifically on the children, contented in each other's arms. The mother holds up one hand to her husband's chest in a gesture of intimacy that links husband and wife together physically (as the children also are linked). And yet her gesture also contains an element of restraint, as if she were warning against waking the children. In this way, the mother's gesture quietly asserts her control over the domestic sphere. Domestic Happiness is based on a drawing of Spencer's oldest sons, who were among her thirteen children. Taken as a whole, Spencer's images glorify the domestic piety of female-dominated sentimental culture. They cherish sincerity, empathy, and feeling above logic, efficiency, and rationality-catchwords of commercial culture. Although women of Spencer's era were not allowed to vote, own property independently of their husbands, or hold political office, they nonetheless exerted considerable power over public opinion and the social issues of the day. They did so through their influence at home-in the nursery, drawing room, and bedroom-as well as in public spaces, such as the church, schoolhouse, and assembly hall, and in women's magazines.

"SENTIMENTALISM IN NATURE." Sentimentalism was such a 'backbone of American mid-nineteenth-century culture that its trace is visible even in the natural-history illustrations of John James Audubon (1785-1851). Many of his 435 watercolors of American birds treat his subjects as if they were members of a household. For example, the Carolina Parakeet, first painted in 1825, places a young parakeet, which has not yet developed the colorful plumage characteristic of the adults, in the lower center of the image (p. 170). The immature bird is surrounded by an adult female, below, and two males, directly above it. This protective triangulation is reinforced by the branches of the cocklebur tree that surround and enclose the young bird. The adults gesture aggressively toward the viewer, as if warning us away from the guarded space of the family. The young parakeet, with its turned head, appears to meet our eyes; the female faces us directly. This eye contact establishes empathy between viewer and birds, which softens their warning to keep our distance.

Sculpture

Sculpture proved to be ap especially fertile ground for sentimental values. During the antebellum years, a wave of American artists, many of them women, sailed for Italy to seek their fortunes. They learned very quickly to adapt neoclassical conventions to the rising taste for sentimental images.

There were many reasons why America's first generation of sculptors would congregate in Rome. The purest white marble-the same marble used by Michelangelo and other Renaissance artists-was still available in quarries in Carrara and Lucca. Examples of Greek and Rm.pan sculpture were visible everywhere in Italy. And unlike the United States, Italy had a long tradition of stone carvers and artisans, who could translate the artist's vision into a finished work.

Most American sculptors worked in clay or plaster. They created small models, which their Italian assistants would then translate into full-sized marble works. The rates for such skilled labor were fairly standard and relatively inexpensive, and American artists soon developed a reputation for paying better than their European peers.

This division of labor between the artist, who conceived and modeled the work, and the stonecutter, who actually executed it, gave women artists a special opportunity. Not only could they live lives less encumbered by gender roles; they could also create life-size and monumental sculptures without engaging in the arduous labor required to carve marble. The community of American woman artists in Rome grew so large that at one point the author Henry James, looking back to their heyday at mid-century, described them as "the white marmorean flock," a reference to the pure marble that they used and, perhaps less kindly, to their visibility as women sculptors in Rome.

Sentimentalized sculptures were often purchased by Americans visiting Europe on the Grand Tour. While in Rome, they would visit the studios of American artists, seeing finished products as well as works in progress. They could have a portrait bust of themselves modeled rapidly in clay or plaster, and then return at the end of their Italian journey to pick up the finished piece in marble. Because the carvings were replicated from an original plaster cast, additional copies could readily be made for other family members or other patrons. Sculpture in marble proved to be a medium oddly amenable to the world of early mass production.

Neoclassicism provided American sculptors with exactly the right style. The dominant mode in European sculpture, Neoclassicism emphasized idealized figures and decorously balanced form. Sentimental culture tended to idealize women as "angels of the household," associating them with purity, innocence, simplicity- values that neoclassical sculpture, with its chaste forms in white marble, could convey naturally.

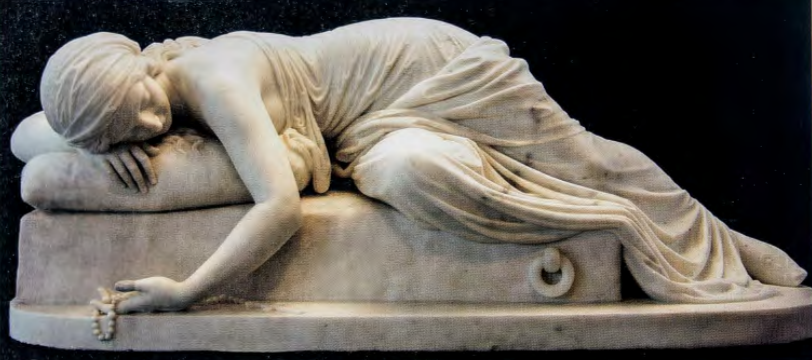

HARRIET HOSMER. A marble sculpture entitled Beatrice Cenci (1856), by Harriet Hosmer (1830- 1908) weds neoclassical sculpture with sentimental values (fig. 6.2). The story concerns a young sixteenth-century Roman woman who was sentenced to death for planning the murder of her father, who had been physically abusive to her brother and sexually abusive to her mother and herself. Hosmer shows the heroine lying quietly on a prisoner's bench, contemplating her fate and holding rosary beads in her languid left hand. Viewers cannot help but notice her youth, beauty, and piety. The pillow on which she rests her head, though carved from marble, appears soft and downy, an appropriate support for Cenci's sinuous body. The story of Beatrice Cenci was published throughout the nineteenth century as a sensational tale of extreme emotions, but Harriet Hosmer has cast it instead as a narrative of female piety and family justice, the triumph of a spiritually exalted woman over wrongs inflicted by a man. Beatrice Cenci's serenity and faith-seen in her calm devotion to her rosary-confirm all that sentimental culture wanted to believe: women's purity, selflessness, and devotion to family.

EDMONIA LEWIS. The Old Indian Arrowmaker and His Daughter (1872), by Edmonia Lewis ( c. 1845-1905), treats a very different-though equally sentimentalized- father-daughter relationship (fig. 6.3). Lewis, the daughter of a Chippewa mother and an African American father, was educated at Oberlin College, the first college in the United States opened to blacks, Native Americans, and women, as well as to white men. Eventually making her way to Rome, Lewis created sculptures that explored racial concerns in a neoclassical idiom. She portrays this elderly Indian as a craftsman. Although he may be old, he is not, as most whites believed, a doomed member of a vanquished race; instead, he gazes with his daughter into a promising future . By giving father and daughter a craft, Lewis endows them with the values of hard work and independence that her middle class patrons espoused, while also suggesting the existence of sentimental family values among people supposed, by these patrons, not to possess them.

HIRAM POWERS. Perhaps the most notorious moment associated with sentimental sculpture occurred in 1847, when the Vermont expatriate artist Hiram Powers (1805-73) sent his Greek Slave (1843) on a tour of major cities in England and the United States (fig. 6.4). Powers was well aware of the potential for scandal that his unclothed figure might cause, but by a combination of clever craftsmanship (her left hand covers her genitals) and brilliant advertising he succeeded in convincing the public that his statue was entirely proper. A pamphlet accompanying the tour of the Greek Slave explained that Powers's figure was unclothed against her will.

Powers imagined the Greek Slave as a Christian woman recently captured by Turkish invaders eager to place her on the auction block. Her family, according to the narrative, had been murdered by the invaders, while she remained the sole survivor. Her modest demeanor and down-turned eyes revealed her resignation and Christian meekness. The chains binding her hands reinforced the viewer's sense of her vulnerability, eliciting feelings of sympathy and concern from both male and female viewers. Though entirely naked, Powers's Greek Slave stood as a model of sentimental propriety.

At the same time , the statue also enabled the viewer to regard a female nude without conscious feelings of voyeurism. The Unitarian minister Orville Dewey wrote, upon seeing the statue, that "the Greek Slave is clothed all over with sentiment; sheltered, protected by it from every profane eye. Brocade, cloth of gold, could not be a more complete protection than the vesture of holiness in which she stands." 1 As the art historian Joy Kasson notes, Dewey's comments, in effect, reclothed her nude body in the invisible robes of Christian virtue. The "civilized" viewer would now, according to Kasson, "see the Greek Slave without seeing her body at all." What the viewer beheld instead was a quintessential sentimental heroine: spiritual and chaste.

If women viewers beheld the Greek Slave as the embodiment of sentimental virtue, they might also have seen her as emblematic of their own social limitations-as captives in their roles as mothers and wives. If so, then Powers's heroine functioned in contrasting ways: as a reminder not only of what sentimentalism required of women, but also of how it worked to empower them. The statue's stoic demeanor suggested both resignation and, implicitly, resistance, a willingness to stand up to oppression and engage it-if not overtly, then by sheer force of character.

Gothic America

In 1840 Thomas Cole-who is better known for landscape paintings (see Chapter 8)-painted The Architect's Dream for one of his patrons, Ithiel Town, of New York and Connecticut (fig. 6.5). Town was an architect, and this large canvas positions him lounging among architectural design books against a panorama of the history of Western architecture. In the distance an Egyptian pyramid and hypostyle hall, and in the middle distance a Greek temple and Roman aqueduct, lead forward in chronological order to Renaissance forms just above the figure on his majestic pedestal. Set apart on the left and in shadow, a Gothic church glows from within, its silhouetted spire pointing heavenward, mimicking the forms of the trees in the midst of which it nestles. The architect holds in his hand a plan on which we see a classically derived portico similar to that behind him, but he gazes raptly at the Gothic building with its steep roofs, cross gables, agitated skyline, and lancet windows fitted with colored glass. The turn to the Gothic that this gaze represents entails a turn from the authority of classical design ideas- which had held sway virtually uncontested for more than a century-to those thought more native to countries in northern Europe (Britain, France, Germany), the culture of origin for most American citizens in 1840. It also entails a turning away from designs associated with rationality, clarity, symmetry, straight lines, and right angles to designs more closely associated with emotion, irrationality, mystery, asymmetry, and irregular diagonals.

LYNDHURST, BY ARCHITECT ALEXANDER JACKSON DAVIS. What exactly did antebellum Americans like about the forms, plans, and aura associated with the Gothic? And what does this enthusiasm tell us about them? A close look at one of the most ambitious buildings in this taste, Lyndhurst, in Tarrytown, New York, is instructive (fig. 6.6). Lyndhurst was built in 1838 with substantial additions in 1865- both phases de.signed by the architect Alexander Jackson Davis (1803-92)-and was owned by a sequence of men prominent in politics and business in nearby New York City. Built of gray cut stone, Lyndhurst exhibits the earthy colors, busy skyline, pointed tracery windows, and steep gables characteristic of the Gothic style. Individual elements, including stained glass, bay windows, and wraparound verandas, exemplify antebellum attention to visual effects-the coloration of interior light, the breadth of view available from the interior, and the invitation to enjoy nature from extensive porches.

Unlike Georgian or Classical Revival forms, the structure is irregular and unpredictable. Its surface is punctuated by windows that vary in size, character, and treatment; masses jut forward or step back, rise into many stories or hug the ground. Lyndhurst is a house that exhibits an interest in surprise and in shadows. This latter characteristic also suggests curiosity about the darker regions of the human soul.

A Gothic Revival structure is marked not only by outward signs of medievalism but also by distinctive elements. Unlike the Georgian or Classical Revival building, in which the overall volume, proportion, and footprint is established first and the rooms accommodate themselves to this predetermined shell, the Gothic structure gives priority to interior space. Gothic buildings express, in their footprint, exterior facade, and massings, the character and uses of their individual rooms. These rooms frequently protrude into space and extend beyond traditional rectilinear patterns.

Five aspects of Lyndhurst represent novelties in American building that appeared with the Gothic Revival and have tended to persist to the present. First, the tall bay windows, which light the dining room at the left end of the building, take the form of a grand window in a medieval hall, which marked the place where the lord sat at table. Second, the library, which developed into a space set aside from other activities-becoming an area devoted to books, reading, and the imagination. Usually associated with privacy, privilege, and male retreat, the library is found in even rather modest homes in this and subsequent periods (becoming known in the mid-twentieth century as the "den"). Third, the great hall, a double-height room with elaborate truss overhead, marked on the exterior at Lyndhurst by a grand window evocative of a west window in a cathedral, recalls the gathering, eating, tale-telling, trophy-displaying place for the lord and his warriors in medieval buildings. At Lyndhurst the great hall is a picture gallery, hung with artistic "trophies." It provides an unusual prospect of the Hudson River through its grand window, which is inset with magnifying lenses, providing watchers with a binocular view of the passing events on the river outside. Fifth, Lyndhurst sports an exemplary tower. A characteristic of both churches and castles, towers spoke "medievalness," and therefore "feeling," more forcefully than any other feature of the building.

MOSS COTTAGE, OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA. Because of its presumed affinity with nature, the Gothic style was most popular in rural settings and in the new horsecar suburbs springing up around major cities. Like other revival styles (see below), it could be found throughout the country, including California, where Moss Cottage was erected in 1864 (fig. 6.7). Less than eight decades after the Spanish missionization of northern California and the conversion of the landscape to large-scale cattle ranching, and only fifteen years after the Gold Rush brought European immigrants and U. S. citizens flocking to the newly acquired territory, the banker Joseph Moss built his house on the edge of Oakland, near San Francisco. He hired the architect S. H. Williams (who, in turn, made use of design books) to realize his Gothic soul. Both the house and the thirty-page contract survive to clarify ,Moss's intent. Two features stand out. First, despite its "medieval" costuming, with steep gables trimmed with ornate bargeboards, the house is technologically avant-garde . Piped for hot and cold running water, it was equipped with flush toilets, a French tin-lined copper bathtub, and Italian marble countertops. It was lit by gaslight, generated by a gas plant on the property Second, the contract specifies nine different kinds of wood, each selected with an eye to use, aesthetic effect, resistance to rot and insects, and smoothness (redwood, mahogany, cedar, eastern white pine, among other species). Such planning indicates the existence of a national market in lumber even before the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Moss Cottage thus represents a moment when northern European culture was self-consciously planting itself on the Pacific Rim, combining architectural forms from the eastern seaboard and Europe with the most recent technological advances. The house exhibits the sort of American know-how and ingenuity that was rapidly gaining an international reputation.

GOTHIC REVIVAL FURNISHINGS. Inside the home at mid-century, furnishings emphasized comfort (with the advent of innerspring upholstery) and alluded, in their design, to a variety of historical eras. Furniture began to be made and bought in "suites." Tables and chairs were left in the middle of the room in conversational ensembles (as they are today) rather than pushed against the wall, as in the eighteenth century, when not in use. Perhaps the most dramatic furniture from the mid-1800s, the dining-room sideboard evolved from the cabinet-and-serving surface we considered earlier in the neoclassical version of c. 1800 (see fig. 5.23) into a towering and expressive piece of sculpture. The sculptural program on the grandest of these sideboards combines a Renaissance Revival form with "Gothic" motifs and usages (fig. 6.8). Although derived from French precedent, this sideboard is Americanized by its crowning feature-a bald eagle atop a shield of the United States. With its aggressive posture, this eagle is explicitly in search of prey. A Native American bow across the shield recalls the hunting so central to Native and to medieval baronial life. An unquiet object, this magnificent sideboard evidences the capacity of power tools to simulate hand carving in this period. At the center of the composition beneath the dramatic trophy stag, two caryatid hounds flank a pair of game birds, whose sheltering greenery forms a bull's-eye at the diners' eye level. Its vivid references to predators and hunting suggest a certain obsession with masculinity and an anxiety about gender roles among its industrial-era owners.

THE AMERICAN WOMAN'S HOME. One major source for the popularization of the Gothic style was a text about house management of the mid-nineteenth century, The American Woman's Home, by Catherine E. Beecher and her sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, better known for her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. The Beecher sisters explicitly identified the Gothic-style home with Christianity, with nature, and with women's responsibility to make the nurturing lessons of the home's architecture, furnishings, and natural setting explicit for children. Full of advice about fern-pockets, picture frames made out of twigs, and other natural materials brought indoors, the book also tackles women's responsibilities in ensuring healthy air in the home and establishing an efficiently run kitchen, so as to give themselves more time to nurture a love of nature and virtue in their young charges.

Egyptian Revival

At the same time that Classical and Gothic Revival structures were redefining the way Americans thought about space, the idea of ancient Egypt also attracted followers. If Greek and Roman structures expressed an admiration for public virtue, then allusions to another ancient civilization, Egypt, signaled a darker concern with death and immortality. Egypt was linked in the popular imagination with mummified bodies and time-defying pyramids. Buildings constructed in a neo-Egyptian taste tended to be large and dramatic. When the city of New York needed to erect a new Hall of Justice and House of Detention (1835- 8), John Haviland (1792- 1852) designed it after an Egyptian temple. Popularly known as The Tombs, the structure reminded passersby of the fact of death, the prospect of eternity (or at least long sentences), and the "resurrection" awaiting penitent released felons.

THE WASHINGTON MONUMENT. The best known example of Egyptian Revival taste is the Washington Monument, in Washington, D.C., modeled on ancient obelisks found in Egypt (fig. 6.9). Such obelisks had been transported to Paris, with great difficulty, by Napoleon's armies, and marveled at by subsequent visitors to the French capital, where they enjoyed an international vogue. The Washington Monument, a 555½-foot white marble shaft, was conceived by Robert Mills (1781- 1855), who would later create many other government buildings. Mills's original plan called for a huge Doric peristyle: 200 feet in diameter and 100 feet tall. Designed in 1833, the Monument took more than 50 years to build, including several interruptions, major design simplifications, and the elimination of Mills's grandiose base. As with other Egyptian Revival structures, the Washington Monument is a somber evocation of death and immortality.

A SILVER SAUCEBOAT. On a smaller scale, a silver sauceboat crafted by Anthony Rasch in Philadelphia (c. 1810) combines sphinx feet, a ram's-head spout, and an asp handle (fig. 6.10), an indication of how Egyptian taste extended to items of household use as well as to buildings. By turning Cleopatra's asp, whose bite brought about her death, into the handle of the sauceboat, Rasch has given the act of dining arresting immediacy. Structuring the sauceboat so that the diner grasps the asp to enjoy the sauce, Rasch is inducing a state of pleasurable discomfort that was an important dimension of antebellum aesthetics. Pain and terror, when experienced at a safe remove, can result in pleasure, or so Edmund Burke theorized and Rasch realized.