6.3: The Cultural Work of Genre Painting

- Page ID

- 232308

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)"Genre painting," a catchall term for anecdotal, often humorous or didactic scenes from everyday life, flourished in antebellum America. These paintings portrayed various character "types" - easterners, westerners, city dwellers, country folk, rich people, poor people, dandies, beggars, merchants, housewives, children, servants, and slaves with varying degrees of admiration, sympathy, respect, and, on occasion, disrespect and disdain, reflecting the attitudes of the middle class for whom they were intended. The middle class, however, was not a single, cohesive entity, but was made up of multiple factions with competing interests. Genre paintings, too, reflect the diversity of their audience. Beyond their anecdotal humor, genre paintings sometimes rendered an idealized version of the United States as a nation without conflicts, class divisions, or industrial disruptions. Although genre painting appears to reproduce everyday life, in fact, it only renders a version of it shaped according to certain social, political, or class imperatives. Genre painting, in other words, employs a realistic style to create a fantasy of public and private life.

Culture vs. Commerce: Allston, Morse, Mount

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, as regional economies expanded and business multiplied the ranks of the wealthy, some observers worried that the ideals of the republic were being trampled on by the stampede to make money. These commentators looked askance at the world of business, which they considered crude and vulgar, an enemy to culture, refinement, and virtue.

THE POOR AUTHOR AND THE RICH BOOKSELLER. Such is the viewpoint illustrated by one of America's earliest genre scenes, The Poor Author and the Rich Bookseller (fig. 6.25), produced in 1811 by the history painter and landscape artist Washington Allston (see Chapter 5). In this picture Allston shows his disdain for commercial enterprise by way of a thin, gangly writer, his pocket stuffed with a manuscript, standing awkwardly on one foot in front of a portly merchant, who sits enthroned while his office boy sweeps away the rubbish- and, in effect, the hapless writer, too. Poking fun at the world of commerce, the picture draws a sharp distinction between the underfed author and the overfed publisher.

THE GALLERY OF THE LOUVRE. Allston's pupil Samuel Morse, painter of The House of Representatives (see fig. 5.20 ), seconded his teacher's disdain for the preoccupation with material success. After a trip abroad in 1829, Morse painted a genre scene that served as both a lecture on European art history and a manifesto of American cultural independence. Called The Gallery of the Louvre (1833) (fig. 6.26), it provides a view of the Paris art museum's Salon Carree, with some thirty-seven Old Master paintings hung on its walls. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century paintings had similarly portrayed vast collections of art treasures, but in those works, the spectators who stroll amid the galleries are kings, dukes, bishops, popes, or, at the very least, wealthy merchants. Here, smartly dressed ordinary men and women mingle among the masterpieces. At home in this great repository, they are duly respectful, but not cowed; the former palace is now their domain. As with Allston's Poor Author and Rich Bookseller, but more didactically and less comically, The Gallery of the Louvre takes the production and distribution of culture as its subject. Its attitude toward Europe is: learn from it, admire it, but do not be in awe of it.

Morse helped found the National Academy of Design, devoted to the advancement of the fine arts through education and exhibition, and he served as its first president from 1826 to 1845. An inventor as well as a painter, he also developed the electromagnetic telegraph and devised its international language, Morse code. Dismayed that the United States was becoming increasingly crude and vulgar, he urged reversing this trend by education and by restricting immigration. As a leading member of the Native American Party, an anti-immigrant organization dubbed the Know-Nothings, he blamed many of the nation's problems on unchecked immigration from Europe, especially Catholics from Ireland and Germany. It was one thing to revere masterpieces of European art, but Europeans themselves were another matter.

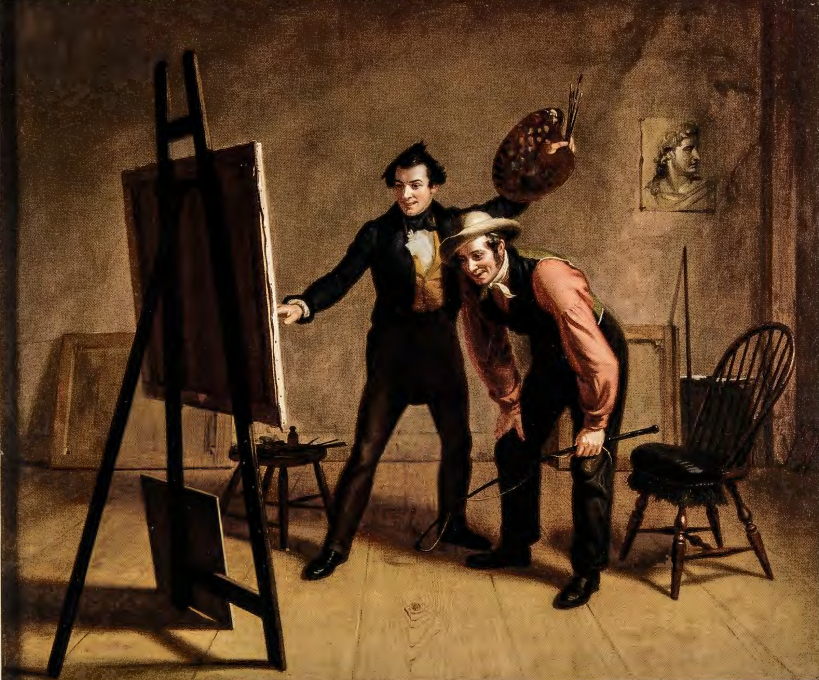

THE PAINTER'S TRIUMPH: A REPLY TO MORSE. Morse's veneration of Old World culture and fear of rampant commercialism struck some younger artists as misguided. One of these was William Sidney Mount (1807-68), whose genre scene The Painter's Triumph (fig. 6.27) scoffs at the high-mindedness of The Gallery of the Louvre. Mount received some training at the National Academy of Design under the leadership of Morse; but finding the academy's principles dry and stuffy, he set out on his own and soon achieved commercial success as a portrayer of daily life on rural Long Island. City dwellers nostalgic for their own country roots were drawn to his quaint and amusing depictions of festive barn dances, boys trapping rabbits, farm workers relaxing in the noonday sun, and rustic gentlemen gathering to make country music.

In The Painter's Triumph (1838), a cocky young artist points delightedly toward a canvas set on an easel in his studio. We cannot see what he has painted, because the canvas is turned away from us, but his visitor, identified as a farmer by his kerchief, hat, and whip, crouches to get a good look and appears to be amused. Perhaps the painting-within-a-painting contains the farmer's portrait Mount was a prolific portrait painter of his neighbors on then-rural Long Island-or maybe it shows a humorous genre scene, of the type Mount was already renowned for painting.

The painter's studio, with its unadorned walls and broad plank flooring, forms a striking contrast to the oversized, crammed grandeur of Morse's Gallery of the Louvre. The long hallway in the earlier painting, receding steeply into space, suggests centuries of European history leading up to the present, whereas The Painter's Triumph is, in effect, free of the past. Mount's painter has turned his back on imported culture, as embodied by the classical Apollo pinned to the wall. Instead, he draws from the life around him. Hence the approving grin of his visitor.

In The Gallery of the Louvre, a young teacher (Morse in a self-portrait) leans instructively over the shoulder of a student, who draws not from life but from art, not from the New World but from the Old. Defying subservience, the artist in The Painter's Triumph (Mount in a self-portrait) strikes a victorious pose, like that of a fencer who cries, "Touche" at a well-executed point. He embodies the attitude expressed in the previous year, 1837, by the New England sage Ralph Waldo Emerson, who declared in his celebrated "American Scholar" address, "Our day of dependence, our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands, draws to a close. I ask not for the great, the remote, the romantic; what is doing in Italy or Arabia; what is Greek art, or Provencal minstrelsy; I embrace the common, I explore and sit at the feet of the low. Give me insight into to-day, and you may have the antique and future worlds."5

Despite such declarations of cultural independence, neither Emerson nor Mount wished to abandon Old World culture. Mount repeatedly drew on classical prototypes for his inspiration, and one might see The Painter's Triumph less as a turning away from European tradition than as an expression of how the American artist mediates between high and popular cultures (the Apollo on the wall and the rustic before the easel) and between the past and the future (the Apollo and the unseen canvas). Whichever way the painting is interpreted, Mount seems more relaxed than Allston and Morse and considerably more good-natured about the business end of creativity.

Woodville: the Pleasures and Perils of the Public Sphere

During the 1830s, Mount was the leading genre painter in America. His anecdotal scenes of country life enjoyed the patronage of wealthy collectors and the general public alike. Newspaper and magazine reviewers lavished praise on him for his talent and observant wit. The art historian Elizabeth Johns has argued that Mount's contemporaries also understood his works to be visual puns that alluded to the politics of the day. Thus two bartering men in Bargaining for a Horse (1835) played on the expression "horse trading," slang for political wheeling and dealing. A scene of farmers making cider alludes to a notorious campaign in which politicians doled out hard cider to prospective voters on Election Day to elicit their support.

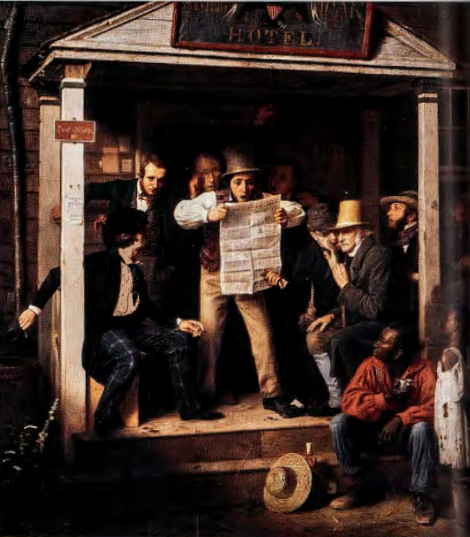

WAR NEWS FROM MEXICO. Equally political was Mount's younger contemporary Richard Caton Woodville (1825- 56). Exhibited at the American Art-Union in 1849 and distributed nationwide in an 1851 engraving, War News from Mexico (fig. 6.28) attracted notice because of its lively depiction of the home front at a time of national crisis. It portrays a sampling of the electorate gobbling up the latest news from a daily paper, which dominates the composition and serves as its focal point.

Radiating outward from the newspaper are eleven figures and the bottom half of an eagle, all gathered under or beside the portico of a combined tavern, inn, and post office identified, with heavy-handed significance, as the 'American Hotel" (hence the eagle). With wide eyes, gaping mouth, and exaggerated body language, the man at center stage reads aloud from the newspaper clutched in his fists.

It reports on the latest happenings in the Mexican War (1846-8), which cost the lives of thousands of soldiers on both sides and resulted in the addition to the United States of 500,000 square miles of conquered territory in the West. The supporting players mug and gesticulate their reactions: one figure, in the shadowy background, throws up his hand; another grasps the frame of his eyeglasses; a third raps his knuckles against one of the portico's pilasters; a fourth, who relays the news to an old gentleman with hearing difficulties, points a thumb emphatically toward the newspaper.

Despite the obviousness of these gestures, it's not altogether evident whether the news is good or bad for the denizens of the American Hotel. Clearly, though, they're all personally involved in what they are hearing, and that includes the humble black man and his little girl in rags; the outcome of the war had a direct bearing on how far west Congress would permit slavery to extend. Those opposed to slavery also opposed the war. The black family is situated at the periphery: they are not part of the consensus, and although they have a personal stake in the war, they have no democratic say in it. A white woman, squeezed to the side of the canvas and visible in the window, is similarly characterized as marginal to the sphere of public discourse, which Woodville shows to be populated exclusively by adult white men. Yet she, unlike the two African Americans, occupies a place securely within, rather than outside, the national hotel.

In Woodville's day, the elderly gentleman in old-fashioned knee breeches would have been understood as a member of the Revolutionary-era generation. His presence in· the scene lends legitimacy to the current military conflict, suggesting that the war that started in 1846 embodied the ideals behind the war declared in 1776. But to the extent that the old man wears a grim or confused expression, the painting implies that '46 is not indisputably the moral successor to '76, and that the values of the present do not necessarily accord with those of the past.

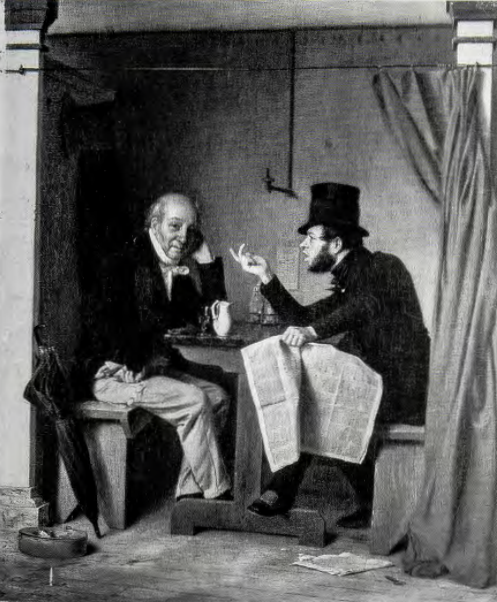

POLITICS IN AN OYSTER HOUSE. In Politics in an Oyster House (1848) (fig. 6.29), two men from different generations sit across from each other in a tavern of the sort reserved for men during the antebellum period to consume shellfish, alcohol, and news of the day. A bearded youth arrogantly ticks off his point of view to his companion while waving the newspaper at his side. The older gentleman turns toward the viewer, as if seeking commiseration for his having to endure the young man's harangue.

The theme of generational conflict was hardly unique to Woodville. In the 1840s, large numbers of his contemporaries ruminated and editorialized at length about the widening chasm between themselves and their elders. In literature and politics, the so-called Young America movement, which recruited to its ranks writers such as Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, advocated breaking away from what they considered to be the tired, dried-up conventions of the previous generation. The Young Americans loudly insisted on the salutary value of fresh and daring new ideas. For many of them, this included wresting California and other western lands away from Mexico so that the United States could achieve its Manifest Destiny-a term coined by a newspaper editor who was also an avid Young American.

In Woodville's world, men of different generations, classes, or politics argue, frown, grin, grimace, disapprove, and deceive. Typically set in male-dominated public spaces and often containing newspapers-symbols of public discourse and debate-these satirical, socially observant genre scenes portray the land of E Pluribus Unum (out of many, one; the U.S. motto) as teeming with tricksters, blusterers, and warmongers. Despite their apparent good humor, they convey an underlying message that the world is a contentious place, full of sharks and charlatans, of which visitors and inhabitants alike must beware.

Street Scenes

Relatively few antebellum genre painters attempted urban street scenes, which by their nature had so many unruly elements to control: multiple figures, faces, still-life objects, architectural structures, and varied light sources. Those exterior city scenes that survive were typically by lesser-known and less well-trained artists, and little has been written about them. Yet they deserve a closer look, for they boisterously, if crudely, depict the American "street" as a thoroughfare of hustlers and go-getters, whose actions are observed by members of the public.

JOHN CARLIN. Take, for example, After a Long Cruise (Salts Ashore) (fig. 6.30). Painted by the deaf miniaturist, poet, and novelist John Carlin (1813- 91), who later became a leading activist on behalf of the hearing impaired, After a Long Cruise shows a pair of drunken sailors making mischief on the docks of New York. One of the young "salts" harasses an attractive and well-dressed African American woman, who, like a winged Nike figure from ancient Greece, flees his grasp, while a second companion upsets a fruit vendor's apple stand. A street youth exploits the windfall. An older sailor, a boatswain with white muttonchop whiskers, attempts to restrain his shipmates, while a bystander looks on with amusement. Although stiff and almost cartoonlike in style, After a Long Cruise pungently combines street-scene reporting and moral commentary, taking as its milieu the shady commercial waterfront, the border zone between sea and city, which also attracted the scrutiny of Carlin's contemporary Herman Melville, the author of Moby-Dick. Carlin transforms racial and class antagonism into a more benign form of humor.

YOUNG HUSBAND: FIRST MARKETING, BY LILLY MARTIN SPENCER. Another street scene is Young Husband: First Marketing (fig. 6.31) by Lilly Martin Spencer (see above). Its urban setting-a rain-slicked pavement on a stormy day-provides a mixture of comedy (the man who takes on the traditional woman's role as shopper can't manage the task), dandyism (the gloved and rakish bachelor who laughs at the young husband), and female sexuality (the raised skirts of the attractive young pedestrian across the street). It also implies a certain level of social disorder, for in Spencer's day the term "husband" referred not only to a male spouse, but also to the administrator or steward of a large household, farm, or estate. Thus, as seen here, the young husband's difficulties may have stood for those of the young nation, which, in the years leading up to the Civil War, struck increasing numbers of Americans as being mismanaged by its political and business leaders.

In this painting, as in the Carlin docks scene described above, the city street is an arena for brisk, impersonal, and sexually fraught encounters between strangers. Portraying pride, indifference, clumsiness, and humiliation, quirky paintings such as these characterize urban America as a comic spectacle meriting the viewer's laughter. They are more raucous than Woodville's paintings and less tightly controlled by academic rules and regulations concerning orderly composition and tone. Yet they, too, picture antebellum democracy not as a smooth unity but rather as a world of individuals in motion, ever about to clash.

Hannah Stiles and the "Trade and Commerce Quilt"

THE APPLIQUE QUILT could sometimes serve as "canvas" onto which an American woman could stitch a pictorial composition akin to a genre painting of the day. In a quilt made in the early 1830s, Hannah Stockton Stiles (1799-1879) took the central "Tree of Life" motif (often used in samplers and quilts) in a new direction, surrounding it on three sides with a riverscape containing eleven large boats and several smaller ones (fig. 6.32). This scene, in turn, is flanked by a border depicting the bustling life of her neighborhood (Northern Liberties) in Philadelphia. Hannah Stiles lived on the Delaware River waterfront at a time when Philadelphia was one of America's busiest ports, bustling with ships from China, India, the Caribbean, and Europe. Her accurate depictions of the paddle-wheel steamers, sloops, and small dories suggests a firsthand knowledge of maritime activity. The men off-loading boards from a sloop and meticulously stacking them between the grocery store and the tavern in the left border of the quilt may have been employees of her husband, a prosperous lumber merchant. From their home on the riverfront, Hannah Stiles chronicled in cloth the commercial transactions as well as activities at local taverns and bathhouses. At the bottom, the artist has stitched men and women in fashionable attire, the women wearing the mutton-sleeved dresses that were the height of style in the early 1830s. The Trade and Commerce quilt is unusual in showcasing the social and economic life of Stiles's day.

Mount: Abolitionism and Racial "Balance"

One of the most intriguing elements of William Sidney Mount's art (see above) is its recurrent attention to race. In his early genre scenes, broadly grinning blacks appear only a step removed from caricature. But in his later works, African American figures take on a central-yet ambiguous-position.

FARMERS NOONING. Farmers Nooning (fig. 6.33), from 1836, shows a group of field hands enjoying a break from their labors. Three young men rest in the shade of an apple tree, and a fourth, reclining on a haystack, sleeps in the sun while a mischievous boy tickles his ear with a piece of straw. The man on the haystack, an African American, commands attention with his beautiful figure, elegantly upturned arm, and noble face. Clad in creamy trousers, a blazing white shirt, and a red undergarment, which shows through with bright crimson highlights, he radiates visual energy, even though sleeping.

Some modern viewers have regarded this painting as a typical nineteenth-century stereotyping of blacks as lazy sensualists; although this field hand, whose pose is based on a classical sculpture of a faun(half man / half goat), snoozes carelessly, one of his white counterparts industriously takes advantage of the lunch break to sharpen his tools. This argument, however, overlooks the white figure stretched out in the foreground with his face buried in his arms. Introducing a more complex response, the art historian Elizabeth Johns has interpreted the painting as an anti-abolitionist political allegory. She notes that the boy tickling the ear of the sleeping giant wears a Scottish · cap ( a "tam-o' -shanter"), an unusual article of clothing, which at the time was routinely associated with abolitionism, inasmuch as Scotland was then the hotbed of the international antislavery movement. This intrusive child may thus symbolize what Mount viewed as the troublemaking abolitionists of the 1830s, dangerously rousing black Americans from the long sleep of subservience.

EEL SPEARING AT SETAUKET. Mount was not progressive in his notions about African Americans, believing that their separate and inferior status was justifiable. He conveyed this view in one of the most intriguing works of his career, Eel Spearing at Setauket (1845) (fig. 6.34). Mount portrays a young white child and his dog seated in the stern of a small fishing craft on a hot summer's day. In the bow, a black woman, most likely a worker on the boy's family farm, leans her weight forward as she thrusts a long fishing spear into the water. The yellowed hillside behind them looks as dry as parchment. Above it, the pale sky is lifeless and blank, save for a vapor that zigzags behind the spear, as if to suggest its motion. The glassy-smooth water mirrors the strip of land and the skiff and symmetrically reverses the directions of the paddle and the spear, forming a series of triangles and lozenges over the flat surface of the picture.

As a result, the painting has a hard, enameled, jewel-like quality and a sort of fairytale simplicity. All is in elemental harmony here: sky and water, dryness and moisture, child and adult, male and female, master and servant-and, in keeping with the artist's own views on the subject, white and black. The picture would seem to say that America is best served by a judicious separation of races, with each keeping its own appointed place on opposite ends of the boat, the two coexisting in peaceful and productive balance. Eel Spearing provided Mount's white clientele with a feeling of reassurance. It maintained child and adult in their separate spheres-she labors while he benefits from her labor-while also suggesting, through its sense of balance, harmony, and timelessness, that white dominance was an entirely natural and universal phenomenon.

Antebellum Anti-Sentimentalist: Blythe

The Pittsburgh genre artist David Gilmour Blythe (1815-65) also painted children. But whereas Lilly Martin Spencer's children appear angelic and mildly demanding, Blythe removes the qualifier "mildly" altogether. In a series of pictures of Pittsburgh newsboys and street urchins that Blythe painted in the 1850s, the subjects are not impish, but demonic. Blythe displays the darkest outlook of any American antebellum genre painter; his children of the street represent base human impulse- unloved and unlovable. We cannot be certain that Blythe's young riffraff were meant to be understood as immigrant, rather than simply poor, Americans. Either way, they threaten the social order-or at least signify its corruption. In Post Office (fig. 6.35), Blythe's masterpiece of cynicism, he shows boys picking the pockets of men and women who gather around a general delivery window but are too preoccupied with their mail to notice. We've encountered the symbolic civic space of the post office in Woodville's War News from Mexico. In that instance, citizens interact in a relatively positive way, but here their only interaction is to push and shove for a place in line-so much for republican civility-and no one gives a damn about anything except his or her own individual news from elsewhere, as embodied by the small sheets of paper they clutch in their hands (in contrast to the large broadsheet newspapers held aloft in Woodville's painting). In War News, the populace faces outward from the American Hotel. Here, civic experience is thoroughly privatized.

Post Office expresses satirical dismay with modern civilization. The heroic bust mounted high above the general delivery window is practically lost in the shadows, ignored by the crowd. Post Office even casts a nod to the famous 'Italian fresco The School of Athens, painted by Raphael three and a half centuries earlier. In Raphael's allegorical tribute to the glories of human knowledge, the great thinkers of antiquity, including Plato and Aristotle, come forward from on high to share their wisdom with the artists, poets, and intellects of Raphael's own era, the Renaissance. Blythe borrows two of the more conspicuous figures in the fresco-the philosopher and truth seeker Diogenes, who sits alone on the marble steps, and the brooding artist and poet Michelangelo, who hunches in the foreground over a sheet of paper-and combines them into a cigar-chomping, monkey-like newsboy on the post office steps.

Like the other genre painters we have examined, Blythe was a keen observer of democratic society. His attention, however, was devoted almost exclusively to flaws. With a jaundiced eye, Blythe sizes up antebellum America as a bleak and dingy place, where corruption trumps honesty, and art records-without correcting-the vices of the times.

Slaves and Immigrants

As a whole, antebellum genre painting served as a looking glass in which the middle classes could flatter themselves and feel morally superior to other social groups. But individual genre artists, reflecting different regions, classes, political parties, and genders, differed from one another concerning the issues of the day. Among these issues were war, abolition, racial divisions, westward migration, family responsibilities, art versus commerce, and the faltering of republican values. Genre painting thrived because-in an era long before the invention of movies and television-it provided an endless succession of lively narrative images that enabled viewers, rightly or wrongly, to make sense of themselves, their neighbors, and their world.

Racial prejudice in the United States did not spring up overnight. Instead, attitudes toward race developed over time, reflecting changing social, economic, and class imperatives. In the 1830s and 1840s racial and ethnic stereotypes began to proliferate. We have already seen this in paintings by Mount, Woodville, and Carlin. Initially, such stereotypes applied as much to immigrant groups like the Irish as they did to African Americans. Writers of the period described the Irish with terms such as "childish," "irresponsible," "primitive," and even "simian." By mid-century, over half of New York's population was foreign born; immigrant workers dominated the industrial labor force in cities up and down the eastern seaboard. As the tide of Irish and then German immigration rose over the next two decades, native-born citizens, fearful for their jobs and their way of life, expressed their hostility in political action.

JOHN QUIDOR. Two paintings by John Quidor (1801-81), both from the 1830s, suggest the dynamics of antebellum racial sentiment. Name calling and race baiting could be aimed in a variety of directions. In Antony van Corlear Brought into the Presence of Peter Stuyvesant (1839), Quidor jumps on board the bandwagon of anti-Irish sentiment (fig. 6.36). Although the painting includes an unflattering image of a wildly dancing black man, it directs its social disdain at the Irish immigrants portrayed in the background. In an earlier painting, The Money Diggers (see fig. 6.37), Quidor lampoons the black man scrambling from a pit in the painting's foreground. The two paintings together demonstrate the ways that animosity against the Irish could spill over into an antagonism against blacks. No record survives of Quidor's political affiliations. Judging from his art, however, he probably would have felt quite comfortable at a local gathering of the Know Nothing Party.

Quidor grew up in Tappan, New York, a stone's throw from Washington Irving's estate in Tarrytown, and his paintings often derive from incidents in Irving's stories. The lower Hudson River Valley, where Quidor spent his childhood, underwent rapid change in the first half of the nineteenth century, in part because of the Erie Canal, which opened New York to the West in 1825. What had once been a region of small farmers turned into a region of factories and growers producing for an export market. People who struggled to meet the needs of an industrializing economy soon grew to resent the unskilled immigrant laborers who competed for their jobs. Quidor was one such figure. He received little recognition during the antebellum years, instead supporting himself as a painter of signs, fire engines, banners, and coaches. He traveled from New York to Illinois at one point in his career, trying his hand at religious paintings in the style of Benjamin West. In the early 1850s he returned to New York, where he resumed painting images from Irving's stories. Quidor was absent from most histories of American art until his rediscovery in the mid-twentieth century.

Antony van Corlear Brought into the Presence of Peter Stuyvesant draws on an incident from Irving's Knickerbocker's History of New York. The painting reaches back two centuries to the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam in order to explore issues vital to 1830s America. In Irving's comic tale, Antony van Corlear, the town crier of New Amsterdam, has been summoned by Peter Stuyvesant, director-general of the colony of New Netherland, to explain his unparalleled popularity among the women of the city. He responds to Stuyvesant's questions by "sounding my own trumpet," an act of self-assertion that turns Irving's laconic tale into a burlesque of the every-man-for-himself individualism associated with Jacksonian democracy.

The painting works visually as a staged battle between images of order and symbols of disorder. The older Dutch establishment, represented by the seated figure of Stuyvesant, has been challenged by van Corlear and his "delectable" trumpet. Both the sentry at the door and the older gentleman cradling a musket between his legs listen intently to van Corlear's musical "charge." Their postures are repeated and parodied in the figure of Stuyvesant himself, whose outstretched wooden leg, dangling sword, and erect cane all suggest the erotic appeal of van Corlear's trumpet. Even van Corlear's belt, designed to hold in his rotund belly, sits high above his waist, as if it too had given up on any effort to contain the man.

Quidor's painting links Jacksonian individualism with unruly social behavior. It also delves into deeper ethnic and racial issues. The black man on the left, gesticulating in stereotyped fashion, is paired with the baying dog at the window on the right. The figures visible across the street from Stuyvesant's chambers respond to the trumpet blast by pressing against the balcony railings. They are associated visually with Irish immigrants, linked in Quidor's painting to drinking, taverns, and revelry. They stand poised to overrun Stuyvesant's chambers, which are guarded only by the glum sentry in the doorway. We can anticipate their success, their ability to overwhelm what little order still exists in Stuyvesant's office, by the signs of chaos already visible in the room: the proliferation of phallic forms, the burst breeches of the gentlemen, even the tri-corner hat lying haphazardly on the floor. That hat would have suggested to a nineteenth-century audience the attire of the Founding Fathers. By dropping it randomly onto the orderly grid of the floor tiles, Quidor hints at the disarray that lurks everywhere in the painting, a disarray associated in particular with the threat of Catholic and Irish immigration.

The politics of the painting, like the later policies of the Know-Nothing Party, link the Democratic Party-the party of Andrew Jackson-with pandering to immigrants and a betrayal of the ideals of the Founding Fathers.

Although Quidor lumps blacks and Irish together in Antony van Corlear Brought into the Presence of Peter Stuyvesant, he seems most concerned about the latter, who threaten the painting's fragile order more seriously than the gyrating black man. Anxieties about black people figure more prominently in Quidor's The Money Diggers (1832) (fig. 6.37). Here, he captures two picaresque Irving characters, Wolfert Webber and the German immigrant "scholar" Dr. Knipperhausen, as they dig by moonlight for buried treasure. They are attended by the "Black Fisherman Sam," who scrambles out of the pit he has dug after spying the ghost of a drowned buccaneer on the ledge above him.

Irving's tale casts a jaundiced eye on human greed. It satirizes the changes to traditional ways of living wrought by a growing market economy. Quidor's painting repeats Irving's larger concerns while shifting the emphasis from greed to race. The burlesque form of the black man in the foreground bears the brunt of the painting's anxieties. He straddles two realms: the nether world of the pit, and the middle-ground space of the two frightened money diggers. Dr. Knipperhausen, the figure to the right of the fire, knocks his knees together at the sight of Sam. His posture resembles that of a man protecting his private parts, an anxiety highlighted in the painting by the string of keys dangling from his crotch. Wolfert Webber turns as if to flee from Sam while staring at the drowned buccaneer on the ledge. Like Knipperhausen, he sports a dangling appendage-a rope-at crotch level. For both men, the emergence of the black man from the pit signals a moment of crisis.

That crisis concerns more than treasure hunting. It centers visually upon Sam and the large pit from which he rises. Quidor' s white characters confront a fantasy of blackness cast as their own worst fear. The spidery tree limbs behind Wolfert not only echo his gestures but suggest a world where people and objects take their shape from the way others perceive them. Tied to the realms of nature and the body, Sam is both human and subhuman. He haunts Irving's two bumbling heroes as much as does the figure of the drowned buccaneer, with whom he is allied visually Both appear unexpectedly out of darkness, and each represents an element of antebellum society (greed, slavery) that Wolfert and his companion would rather ignore. The painting hints at the way that white society has buried or held at bay its anxieties about slave-holding-anxieties that are destined to resurface over time.

The irony of Quidor's painting lies in what happened next. Four years after Quidor completed The Money Diggers, the U. S. House of Representatives, fearful about the divisive effects of slavery, sought to suppress all further Congressional debate on the,issue. They passed legislation known as a "gag rule," a procedure that automatically tabled any antislavery petition brought before the House. Quidor's painting suggests the ultimate futility of such efforts.

MINSTREL SHOWS. In The Money Diggers, Quidor's two white figures confront the specter of race in American history through the figure of a frightened black man. Quidor's portrayal of African Americans derives from two sources: printed images, which circulated in ever-greater numbers throughout the antebellum period, and a new form of entertainment, the minstrel show, which began appearing in frontier towns up and down the Ohio and Missouri Rivers in the 1830s. The Money Diggers shares with the minstrel show a sense of burlesque humor bordering on the grotesque. The painting's stage-like space, together with its drama of white characters responding to the antics of a black man, repeat the relation of white audience to blackfaced performers familiar from minstrel shows of the period.

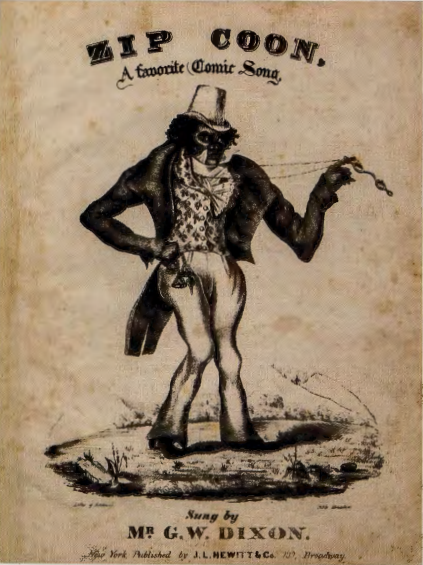

Minstrel shows-parodies of black slave life on southern plantations- featured white entertainers who 'blacked up" by rubbing burnt cork on their faces. They painted their lips ruby red, donned tattered clothing, and maintained a toothy grin throughout their performance. Characters like Jim Crow, a gullible country fool, and Zip Coon, a city dandy and trickster, spoke in broken English punctuated by double-entendres and other sexual innuendo (fig. 6.38). They delighted their audience by behaving like naive and mischievous children, gesticulating in outlandish fashion, and dancing with abandon. Minstrel shows drew immense crowds throughout the nineteenth century. They traded on a notion of African American culture as primitive, lustful, and undisciplined. In this way, African Americans came to embody a degree of sensuality that most audience members felt was lacking in their own, more "civilized," lives. White audiences viewed the minstrel show with mixed feelings of pleasure and contempt: pleasure at the world of childlike antics that they found on the stage and contempt for the exhibition of behaviors they could never condone in themselves.

Minstrel shows did more than satirize black life; they helped European American audiences overcome their own ethnic and social divisions. By identifying African American culture as the "other," as that which is both desired and repudiated, minstrel shows allowed native and immigrant workers to transcend their class and economic differences, to see themselves collectively as white, and to separate themselves from black working-class culture. They knit together a variety of competing ethnic groups (Irish, Scottish, German, and native-born laborers) and potentially antagonistic classes (wage workers and shop managers) and united them all under the banner of whiteness.