5.2: Classical America

- Page ID

- 232303

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In 1795, George Washington was halfway through his second term as president. The long journey toward nationhood had begun, each step forward producing increased confidence at home and growing respect from abroad. Alexander Hamilton, the brilliant but arrogant secretary of the treasury, sought to diversify the economy of the new republic, rendering it less reliant on agriculture and more committed to commercial development. His economic policies dovetailed with a policy of American neutrality toward France and Britain, again at war as a consequence of the French Revolution. American ships transported goods from both nations, resulting in a decade of peace and prosperity.

But advances in the realms of diplomacy and foreign trade were offset by problems on the domestic front. The Federalist Party- the party of Washington and John Adams- favored manufacturing, growth, and a strong national government. Their policies provoked protest from southerners fearful of northern dominance, from mid Atlantic states resentful of federal tax legislation, and from farmers hostile to manufacturing interests. These constituencies formed a new coalition behind Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson's election to the presidency in 1800 marked the end of Federalist policy. The new century brought with it more egalitarian social practices and a more diversified electorate.

Americans felt confident about embracing novel forms of government because they did not believe that such forms truly broke with the past or relied upon untested models of human nature. They viewed their republican experiment instead as a return to a lost golden age. They felt that the conditions for virtue that had existed in ancient Greece and republican Rome could be recaptured, encoded, and taught in the New World. Jefferson and his colleagues believed that freedom without virtue resulted in mayhem: unbridled personal appetite and will. Thus the form of architecture they favored, Neoclassicism, was not merely a style, but an embodiment, a way of being in the world, which involved emotional, ethical, and political engagement. It was also a form of mimicry. Bits of ancient building vocabulary columns, capitals, entablatures, and pediments-were adapted imaginatively. The goal of such adaptation was political: to achieve, by suggestion, a republic of virtue.

The classical world was known to Americans and to early nineteenth-century Europeans in three ways. First, some people (including Jefferson and Copley) traveled in Italy and southern France to study antiquity firsthand. Second, images and descriptions of ancient buildings and structures by Renaissance architects such as Palladio were widely available to Americans in books (see Chapter 4).

Book knowledge of antiquity stressed the orders and rules concerning proportions based on surviving temples and architectural fragments. A third new source of knowledge became available late in the eighteenth century, when systematic archaeological excavations were begun at Pompeii and Herculaneum, two Roman cities near Naples that had been overwhelmed by the cataclysmic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 C. E. The discovery of the sites in the mid 1700s and the subsequent slow removal of a thick blanket of soil and ash exposed ancient Roman domestic structures, wall paintings, and vestiges of daily life, which had been preserved virtually intact. These sites endowed the classical world with an immediacy and intimacy formerly unknown.

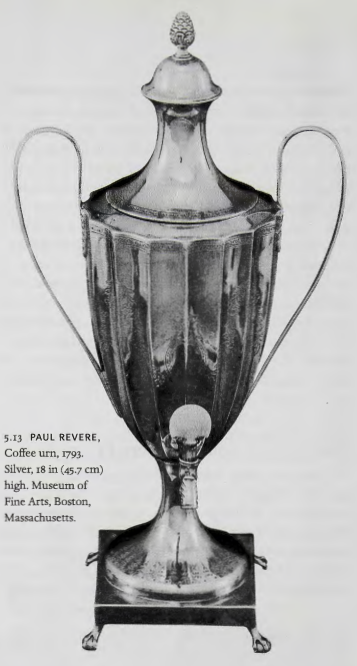

For a post-Revolutionary generation, classical forms bestowed an aura of moderation, rationality, and balance on all they touched. They had the power to turn consumer objects into civic lessons. Paul Revere's coffee pot of 1793, shaped like a Greek urn, endowed a utilitarian object with the values of the classical past (fig. 5.13). Designed to keep coffee hot and to dispense it through a spigot at the bottom, this vessel combines two motifs of antique design: the fluted column (its concave ribs evoke the graceful shafts of Corinthian columns) and the funerary urn. Revere's coffee urn served not only as an object of status for its owner but also as an emblem of the owner's patriotism, of values that linked America with the classical past. We call this style "neoclassicism."

Objects in the neoclassical style helped reassure commercial and intellectual elites that the times had not gotten out of hand. By highlighting symmetry and balance, they suggested that moderation would prevail in politics as it did in fashion. Neoclassicism, though also popular in Europe, was particularly well received in the young United States. The style invoked the virtue and uncorrupted "youth" of Western civilization, given here, on a "new" continent, a second chance.

Thomas Jefferson's Western Prospect

For more than fifty years, from 1768 until 1822, Thomas Jefferson designed buildings and landscapes. While serving as a delegate to the Continental Congress, governor of Virginia, minister to France, and secretary of state (in Washington's presidency), vice president (under John Adams), and president, he also devoted thought to buildings and the organization of social space. Jefferson's three principal architectural projects are his home, Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia (1769- 84; 1796-1809 ), the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond (1785- 96), and the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville (1817- 26). These three structures bear the stamp of his own considerable genius, but they are also expressive of concepts he shared with his generation.

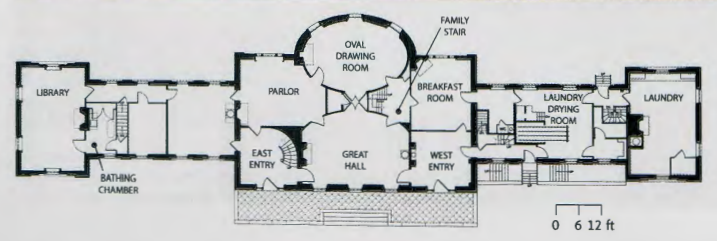

MONTICELLO. In its final form, Monticello is a symmetrical domed structure of one main story with a hidden second story, between an extensive ground-level series of service and storage rooms (invisible from Monticello's main, western entrance) that extend in bracketing arms, terminating in two small dependencies (fig. 5.14). One of these was the first structure on the site, and it served as Jefferson's home during years of the extensive building campaigns. The completed structure (familiar to us from its image on the back of the nickel coin) crowns its rural mountaintop and evokes the man himself. Not much bigger than a large suburban tract home built today, Monticello nevertheless marshals extraordinary dignity and presence.

The population at Monticello during Jefferson's lifetime was considerable, as this was not just a home but the management center of a 5000-acre farm. Tobacco was the cash crop until 1794, succeeded by wheat. The visual subordination of the service corridors (and those who served), by banking them into the hillside so that they are at convenient ground level on the 'business" side and invisible on the view side-is an architectural device that our culture continues to use. The effect is to render all forms of servitude, free or enslaved, as invisible as possible. Jefferson also incorporated into Monticello a number of unique mechanical inventions that aided service and afforded him privacy, including a wine dumbwaiter and a rotating door with service shelf. A specially designed clock, bed, and clothing storage system exhibit Jefferson's fertile mind applying reason, engineering, and ingenuity to domestic life.

Between the windows in the tea room-a bay extending from the dining room, where he and his family took their evening meal-busts of worthy and exemplary men gazed upon the gathering. In the two-story entrance hallway a rather different discourse of objects greeted the family and their visitors. Here classical patinated plaster busts were supplemented by elk antlers, bison and big-horn sheep heads, and Native American paintings on buffalo hides brought back from Lewis and Clark's expedition through the Louisiana territory. In this display Jefferson was continuing a long European tradition in which the medieval hall-the primary gathering and eating space for the lord, his knights, retainers, and household-was hung with trophies of war (armaments and flags captured in battle) and trophies of the hunt (usually antlers) as objects of memory and instruction. Jefferson, with the aid of his friend Charles Willson Peale, was among the first to include taxidermically-treated mammal heads in this room-adding the 'busts" of creatures to those of Cicero and Voltaire.

Monticello, like most freestanding American Georgian buildings, was not designed with a front and a back; rather, it has two facades, one facing east to Europe-toward Rome, Britain, and history-and the other facing west toward what Jefferson understood to be nature and the future. The western facade was built facing the frontier, in western Virginia where the great spine of mountains dividing the Atlantic coastal plain from the Mississippi heartland begins. Jefferson was a western-looking man. He firmly believed that the American form of government depended on personal virtue and civic responsibility, and that those qualities were best nurtured in the farmer, who was rooted economically and emotionally in the landscape.

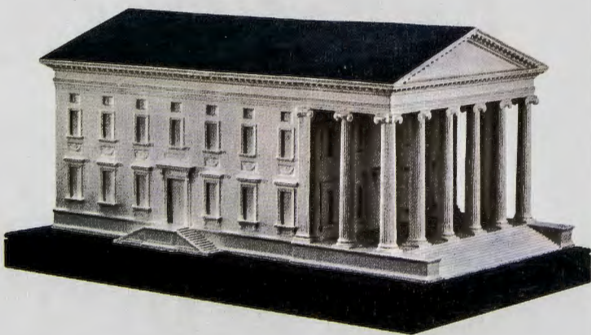

THE VIRGINIA STATE CAPITOL. Jefferson's faith in the West was matched by his lively appreciation of European culture and antiquity. Sent by Washington to France as an emissary, Jefferson found the time to travel to Nîmes, a city that the Romans had occupied two millennia earlier.There, they had built a stately temple that had survived through the centuries almost intact. Jefferson reported in a letter to a close woman friend that he had gazed at this temple, called the Maison Carrée, "like a man at his mistress." The depth of his admiration-emotional and physical as well as intellectual-prompted him to adopt the structure for the design of the Virginia State Capitol. Figure 5.15 shows the scale model that he and his French collaborator, Charles-Louis Clerisseau, sent to Virginia. His search for an appropriate model to contain and express the new politics of his native state had reached a dead end in Paris ("The style of architecture in this capital [is] far from chaste," he wrote in 1785, recoiling from the baroque and modern splendor of Louis XVI's capital). So the Maison Carrée, both "chaste" and his "mistress," was copied in Richmond, becoming the first clone in North America of a whole antique structure.

The Maison Carrée is a Roman temple, a rectangular marble sanctuary set up on a raised dais and fronted with a portico, which announces its importance and through which the building is entered. It is a unitary volume without windows or stories or staircases. Although Jefferson's copy strongly resembles the Maison Carrée, it is also an adaptation, made suitable to house a state government. For Jefferson, the temple form expressed dignity (in the raised dais), permanence (in the use of masonry), clarity (in its symmetrical, axial format), and sanctity (being originally a religious building). It is also alluded explicitly to a "Golden Age" (antiquity) and to the founders of Western political and scientific thought. Moreover, it was associated in Jefferson's mind with republican forms of governance. This temple and the classical revival it spawned represented the repudiation of monarchy and the beginning of a new "Golden Age."

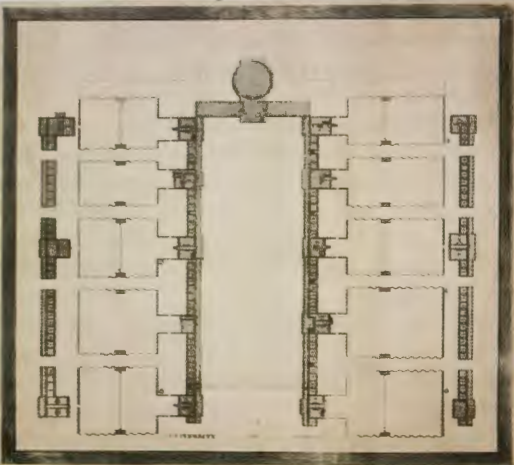

THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA. Jefferson's last and most ambitious architectural project was the University of Virginia (fig. 5.16 A, B ). A departure from other colleges in the United States and Europe at the time, the design established the idea of the college "campus" as we know it. Unlike the single large multipurpose buildings at Harvard, Princeton, and William and Mary (which Jefferson attended), and equally unlike the cloistered colleges at Oxford and Cambridge dominated by their halls and chapels, Jefferson's university is arranged as a hierarchy of structures around an open-ended tree-lined "Lawn." Jefferson described the university as an "academical village."

Surrounding the Lawn in a U-shape is a series of two story pavilions containing classrooms on the first floor and faculty housing on the second. A continuous colonnade fronts a range of one-story student rooms and connects these temple-like structures. Behind, gardens enclosed with serpentine brick walls terminate with more student rooms and larger pavilions, which served as dining halls. Dominating the whole is the Rotunda, based on the Pantheon-a surviving ancient Roman temple Jefferson would have known from books-which houses the library and classrooms. Circular in plan, spherical in conception, and fronted with a grand portico, Jefferson's Rotunda expresses the perfection of geometry and the authority of the classical world. It also symbolically situates the written word and book learning-neither the church nor the hierarchy of academic fellowship-at the heart of the educational enterprise.

Jefferson's university is more than a context for learning-it is a lesson in its, own right. Each of the pavilions arranged along the Lawn is designed to exhibit different facets of the classical architectural orders, although all conform to the scale, intervals, and materials of the colonnade. Jefferson considered the university to be one of his three greatest accomplishments. Disregarding his two terms as president of the United States, he directed that his epitaph should read simply: "Thomas Jefferson, Author of the Declaration of American Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and Father of the University of Virginia."

Capitols in Stones and Pigment

Jefferson's wish to create buildings embodying republican values was shared by many of his contemporaries; the years of the early republic saw the development of new building types to house the new institutions of government. The designs of these public structures included abstract and pictorial motifs that were intended to symbolize the new nation. Americans eager to establish government 'by the people" wanted its philosophical underpinnings expressed in spatial and symbolic form, as well as in the language of the Constitution itself.

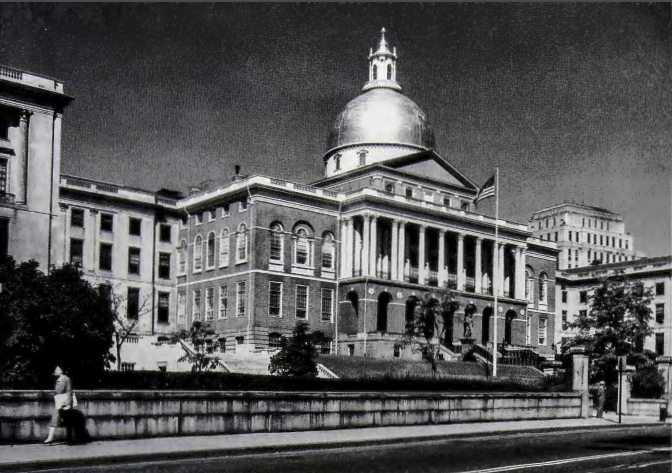

CHARLES BULFINCH, ARCHITECT. Charles Bulfinch (1763-1844), considered today one of the first professional architects in the United States, designed the Massachusetts State House (1793-6) (fig. 5.17). After graduating from Harvard and touring Europe, Bulfinch returned to Boston eager to employ the neoclassical styles he had seen on his Grand Tour. Drawing on his memories of Somerset House, in London, Bulfinch created the Massachusetts State House as a study in balance, texture, and color. The red bricks of the building's classical central block set off the elegant white gallery of Corinthian columns. The gallery sits above a simple arcade of brick arches and flanks rows of gracefully arched, white-trimmed windows on either side. At the center of the State House stands a high wooden dome that was clad in copper soon after the State House's completion. The dome was later gilded to catch the sun's glow. The Massachusetts State House crowns the top of Beacon Hill, overlooking Boston Common, then as now a greensward at the center of the city. It presides over "nature" in a language of symmetry, order, and- with its shining dome- light.

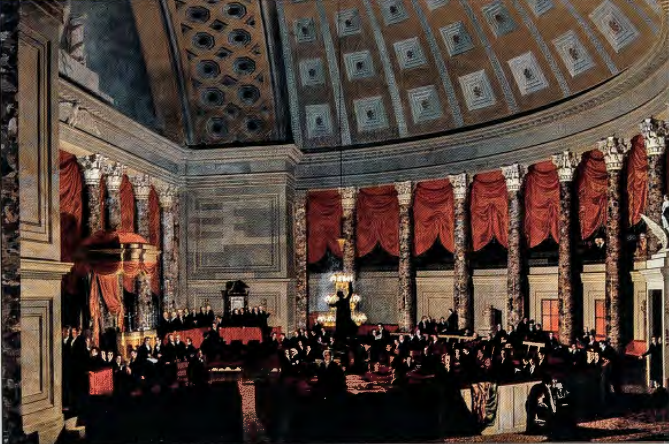

THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL. The United States Capitol was designed as the centerpiece of the newly created capital city of Washington, D. C., a building in which the representatives of the states (the Senate) and of the people (the House of Representatives) would meet to discuss, debate, and persuade by rational argument (fig. 5.18). As conceived by its original architects, the design of the Capitol utilizes three vocabularies: the primary building blocks of geometry (such as the sphere, the semicircle, and the square); the forms of antiquity (such as the column, the dome, the pediment); and agricultural motifs associated with the prosperity of the new nation (corn, tobacco, and cotton). According to the initial plans, the building was to unite under one roof the Senate and House of Representatives, which would rest over a ground floor housing the Supreme Court. A meeting place for these three branches of government was envisioned under the majestic dome where sculptural images of the Founding Fathers would be installed, reminding successive leaders of the heroism and virtue of their predecessors.

Designed originally by an obscure physician from the West Indies, William Thornton, according to a plan favored by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, the Capitol quickly developed into an architectural stew of different historical forms. By the early nineteenth century, it consisted of two separate wings without a center. After the Capitol was gutted by the British, during the War of 1812- a national humiliation- its rebuilding was entrusted to Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764- 1820). Latrobe, who had been professionally trained as an architect, transformed the Capitol's hodgepodge appearance and gave it an increasingly classical look. Latrobe equated rationality with geometric forms; he wished to demonstrate the rationality of nature. He also bestowed on the Capitol a more distinctively American look by inventing three new architectural "orders" or types of column. Latrobe's columns were crowned at the top not by traditional scrolls or acanthus leaves, but by images of corn, cotton, and tobacco, the principal cash crops in the United States. These quirky capitals quickly became the part of the building most admired by the senators and congressmen who inhabited it (fig. 5.19). The modern dome of the Capitol, not completed until after the Civil War, was designed by Thomas U. Walter.

The U. S. Capitol, like Jefferson's Virginia State Capitol, looks backward. It incorporates Roman prototypes as well as Renaissance and Baroque public building ideas, but it also includes iconography specific to the agricultural basis of wealth and trade in the new nation. It is not just a building, but a discourse in stone about the ideological beliefs and hopes of the founders.

A PORTRAIT OF THE CAPITOL: MORSE'S THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. By the 1820s, the older generation of Revolutionary-era leaders believed that the nation was sorely at risk of losing its political vision and social cohesion and that it stood in strong need of political and cultural instruction. These views were shared by an aspiring painter named Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872), who would later invent the telegraph. Morse disapproved of the growing factionalism of American politics; he disagreed with the movement in the 1820s to abolish property ownership as a requirement to vote; and he was alarmed at the shift in power in Congress from an older eastern elite to an alliance of southern and western states, which, he believed, increasingly represented a "vicious threat to stable and correct government."

What better way to counter this lapse from the principles of the Founding Fathers than through the educative powers of art? Morse hoped to provide a model for proper republican government by aligning architecture with painting. His goal was to represent democratic culture as it ought to be, rather than as it was. The idea he hit upon for communicating his political beliefs was a huge portrait of The House of Representatives (1822-23) (fig. 5.20). Morse's ambition for the canvas was twofold: to endow an otherwise fractious and quarrelsome Congress with an air of what art historian Paul Staiti has termed "civic heroism," and to make enough money from the exhibition of his painting to help recoup his dwindling family fortunes. Though Morse was successful at the former, he was a dismal failure at the latter. Not many Americans agreed with Morse's vision of government.

Most people in the 1820s had no idea what their government in Washington actually looked like. Washington in the 1820s was still a swampy, malaria-ridden city. Only those who had business with the government were likely to travel there. Morse felt that a painting of the newly restored Capitol would show Americans not only how their government appeared but how it functioned. It would demonstrate a marriage of great architecture with good government. And it would illustrate, by its example, the decorum and values appropriate to a democratic society.

Morse's painting takes full advantage of Latrobe's neoclassical spaces. The painting highlights the enormous scale of the dome above the House of Representatives, with its illusionistically painted coffers and shadows, its supporting columns (made of stone from a Virginia quarry), and its great oil-fired Swiss chandelier. Critics of the painting found it static and airless. They noted the diminutive size of the figures and accused Morse of draining the subject of any human drama. What little drama there is in the painting lies in the efforts of the House doorkeeper- seen standing on a ladder at the lower center-to light the chandelier.

And yet that august stillness was Morse's point. He wished to present the House of Representatives as a harmonious national body, where congressmen subordinated their individual interests to the common good. Morse in fact painted Congress in a leisurely moment prior to the opening of the evening's session precisely because he wished to avoid depicting the partisan behavior that characterized Congress when in session. The congressmen's casual encounters in the aisles, and their easy familiarity, suggested a unity of purpose larger than any single member's partisan interests. Morse hoped to demonstrate in his painting the social cohesion that he felt resulted from enlightened leadership. The warm glow of the chandelier at the center of the painting suggests that "enlightenment" stems from rational governance.

The White House

PIERRE CHARLES L'ENFANT (1754-1825), designer of the city of Washington, originally imagined the "President's House," as it was then called, as a huge European-style palace. L'Enfant's 1791 plan for Washington called for a building five times the size of the present White House. After George Washington dismissed L'Enfant for insubordination, he chose James Hoban (c. 1762-1831), an Irish-born architect, to design the President's House. Hoban envisaged a traditional Georgian-style structure, with a projecting bay on the south facade and a pediment on the north, or entrance front. Behind the bay he placed the building's most distinctive feature: an oval office.

Construction began in 1793, and in 1801, John Adams became the first president to occupy the still-unfinished residence. During the War of 1812, British troops invaded Washington. They delayed torching the White House until they had first eaten a dinner there that had been prepared earlier in the day for the president. Although the interior of the building was gutted, the facade was left standing. Hoban returned after the invasion to reconstruct the building in collaboration with Benjamin Henry Latrobe. James Monroe was the first president to return to the rebuilt White House, in 1817. The White House took on its current appearance when two porticoes, on the north and south facades, were added in the 1820s.

Domestic Life

During the early republic, houses continued to be constructed along the same basic principles we saw in the late colonial period- symmetrical, hierarchically arranged facades and plans. The most expensive of these homes continued to be two-story, hipped-roof buildings, with five bays (vertical divisions) on the front and a double pile plan. But there were two significant differences. First, surfaces grew flatter and thinner; the transition from plane to plane was less articulated. Gone were the "plastic" (sculptural), three-dimensional quoins, world of colonial architecture. In the words of the English neoclassical architect and theorist Robert Adam:

Movement . . . in different parts of a building . . . adds greatly to the picturesque[ ness] of the composition. For the rising and falling, advancing and receding [and] the convexity and concavity [ of forms] have the same effect in architecture, that hill and dale, fore-ground and distance, swelling and sinking have in landscape: that is, they serve to produce an agreeable and diversified contour, that groups and contrasts like a picture, and creates a variety of light and shade, which gives great spirit, beauty, and effect to the composition.3

GORE PLACE, A NEOCLASSICAL HOME. Christopher Gore, governor of Massachusetts, built a summer house in Waltham (west of Boston), which overlooks the Charles River (fig. 5.21). Gore Place (1801-06), was designed by Gore's wife, Rebecca, together with the French architect Jacques-Guillaume Legrand (1743- 1807?). It was constructed with many modern conveniences, including running water, a bathtub, and a wood-burning, cast-iron cookstove. Reception areas and a grand staircase flow in circular and oval patterns. Its twenty-two rooms include a music room, billiard room, library, family dining room, banqueting room, and butler's room.

These specialized rooms-each designed for a single purpose-were novelties introduced in the neoclassical era. They necessitated the development of specialized furniture, such as the expanding dining table and the sideboard, as seen in Henry Sargent's painting (c. 1820) (fig. 5.22).

The dinner party, as you can see from the painting, was usually an all-male affair-this would not change until the late nineteenth century. The New York-made sideboard in figure 5.23 is a particularly elaborate one. Following the rules of design articulated by Robert Adam, it is a composition of "advancing and receding [planes], with convexity and concavity . . . to produce an agreeable and diversified contour." The function of this large object is threefold: to provide lockable storage of silver and other valuable objects; to provide lead-lined (waterproof) drawers (the tall thin drawers flanking the midsection) at a convenient height, so that bottles of wine could be chilled and kept close at hand; and, most important, to provide a broad surface at standing height from which a waiter might serve the various courses of a meal. The sideboard also served as a work of art to be admired in its own right.

A CARVED MAHOGANY CHAIR, ATTRIBUTED TO SAMUEL MCINTIRE. One of the most important aspects of neoclassical design was its serious tone. The sort of chair Christopher Gore's peers commissioned for dining is illustrated in figure 5.24. Like architecture of the period (c. 1800), it is thinner, lighter, and less sculptural than late colonial chairs. But it is not just a chair. Beyond offering a comfortable place to sit, it composes a little sermon in citizenship and sacrifice. Probably carved by Salem's preeminent architect-designer-carver, Samuel McIntire, its back is shaped like an ancient Roman soldier's shield, and its central feature is an urn- specifically a funerary urn- from which sprigs of wheat sprout. The chair preaches in symbolic fashion that noble sacrifice for one's country yields peace and plenty for the nation. But a second lesson for us lies in its materials- mahogany from the Caribbean, white pine from Maine, ebony from Africa, and silk from China. Together they recite a litany of global trade. The shieldback chair embodies the cosmopolitanism of the early republic when raw materials, finished objects, traders, immigrants, and ideas increasingly came from distant lands.

The China Trade

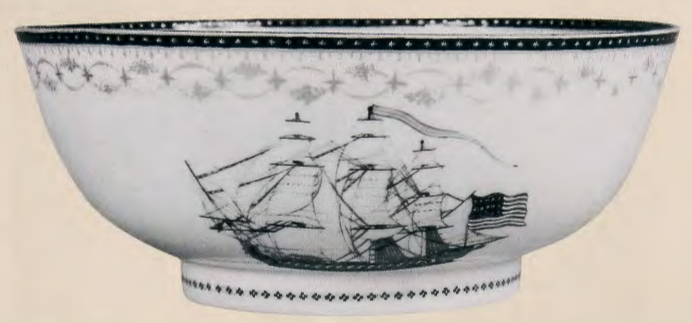

WITH INDEPENDENCE from Great Britain, the scope of American merchants grew broader, soon including direct trade wit.h China. Americans were adept artisans, and their workshops and manufacturies produced fine goods. But there were two things they desired, yet lacked the materials and skills to_ manufacture: silk and porcelain. For these they went to China. The large porcelain bowl in figure 5.25 is Chinese in form and material, but its surface ornament is American. The Chinese painter probably copied a print to draw this gunboat, with its improbably giant flag. The subject, a frigate built in Philadelphia in 1815, reminds us that, in order to protect its burgeoning merchant marine fleet, the young nation had now built a navy as well as civic institutions and domestic infrastructures.

LADIES' FURNISHINGS. The early republic was the first period in which household furniture was made specifically for women. The exquisite lady's writing table (fig. 5.26), with its graceful sliding tambours (bending doors), mahogany veneers, and fine proportions, was made by John and Thomas Seymour in Salem, Massachusetts, 1794-1804. Sewing tables and writing desks like this suggest the sorts of activities women participated in. Colonial laws had mandated that women be taught how to read (see below). The existence of such an object as the Seymour desk points to a culture in the early national period in which some gifted women wrote letters, poems, and in a few cases, such as Mary Otis Warren, author of a three-volume history of the American Revolution, serious works of scholarship.

A Greek Revival Interior

A QUARTER OF A CENTURY after the completion of Gore Place, a new passion for Greek forms and styles succeeded the more eclectic borrowings of Neoclassicism. A watercolor by the architect Andrew Jackson Davis suggests how pronounced the vogue for Greek culture became (fig. 5.27). A screen of stately Ionic columns and pilasters forms a background and marks the space between double parlors. Both rooms are equipped with seating based on chairs and other furniture pictured in paintings on Greek vases (the klismos chair in the middle of the watercolor, for example, derives from a fifth-century B.C.E. Greek vase). Antique forms such as the couch in the corner of Davis's drawing were copied and manufactured by America's most ambitious designers and cabinetmakers. Benjamin Latrobe designed a suite of furniture in the Greek style for the White House in 1809. Sitting on Greek-style sofas allowed a posture of greater repose than furniture of the eighteenth century allowed. Looser, less structured garments, in turn, permitted a freer, more informal disposition of the body for both men and women.

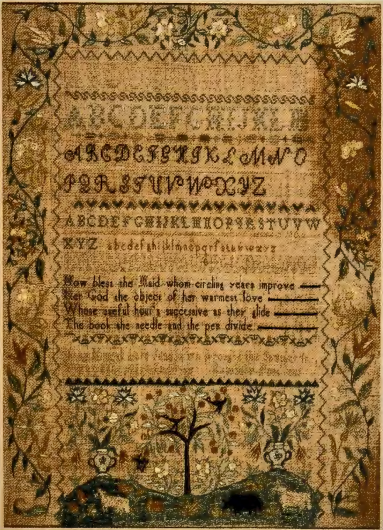

WOMEN'S ARTISTIC EDUCATION. In 1803, twelve-year-old Anne Kimball of Newburyport, Massachusetts, embroidered the following verse on her sampler: How blest the Maid whom circling years improve I Her God the object of her warmest love / Whose useful hour's successive as they glide / The book, the needle, and the pen divide (fig. 5.28). In colonial America, there was a great deal of controversy about how much training in "the book and the pen" young women needed, but it was generally agreed that the needle was the foremost tool in their education. Both girls and boys were taught to read, but in most communities only boys were taught to write. Girls learned to fashion their letters through the use of an embroidery needle.

By the end of the eighteenth century, girls from middle class urban families were sent to private academies, where they learned the skills and accomplishments necessary to their social standing. The women who ran these schools were generally needlework experts, and so girls received first-rate training in this art form. Mrs. Rawson's Academy, in Boston, is a good example. In 1797 Mrs. Rowson placed a newspaper advertisement stating that she would be "instructing young Ladies in Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, Geography, and needle-work." The works of embroidery and painting done at the school were publicly shown at annual exhibitions. Medals were awarded for excellence, and the exhibitions reviewed in Boston magazines. So even before 1800, women had venues in which to exhibit their work outside of the domestic environment. These works were often far more innovative than the earlier samplers that followed English patterns (see fig. 3.35).

Anne Kimball embroidered floral vines on three sides of her sampler. Beneath the alphabet, worked in several types of stitch, and the verse quoted at the opening of this section, the artist stitched "Anne Kimball, born June 14, 1791, wrought this Sampler in The twelfth year of her age Newbury Port 1803." With her needle, she populated an idealized landscape with animals, fruit trees, and flower-filled urns. In contrast to Kimball's idealized pastoral landscape, Hannah Otis's View of Boston Common (fig. 5.29), which measures nearly 30 by 58 inches, is based on a real landscape (the "common," or green park, at the heart of Boston) and a recognizable house (The Hancock house, built in 1737). On the right, she depicted animals frolicking on the Common under the watchful eyes of a gentleman on horseback and his black manservant. This naturalistic landscape, with its accurately rendered Georgian colonial house, rolling hills, flora and fauna, is a masterwork of eighteenth-century American art.

When people talked about "female accomplishments" in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, they were referring especially to fine needlework, music, and watercolor painting, all taught by schoolmistresses such as Susanna Rowson. Such women, who provided guidance in style and subject matter and set the direction for more than a century of female accomplishment, have been called by the scholar Betty Ring "the most neglected of American artists." The regional variety identifiable in samplers is due to the influence of particular teachers, who trained generations of needlework artists in cities such as Boston, Newport, and Philadelphia.

Shortly after the American Revolution, a young Connecticut woman named Prudence Punderson designed and embroidered an allegorical self-portrait, which she titled The First, Second, and Last Scene of Mortality (fig. 5.30 ). Punderson's portrait not only reveals her Christian piety but also sheds light on the domestic mores of an upper-class New England household. On the right, the artist depicts herself as a baby in a cradle, being tended by an African American servant. Above the servant is a picture on the wall, perhaps another embroidered figural scene. The artist presents her adult self in the center of the composition, sitting at a round Chippendale-style tea table, where her artistic materials are displayed. On the left, she has stitched her own coffin, the initials "PP" embroidered on top. This is a female version of the three stages of life, a familiar iconographic motif. Behind the coffin, a mirror is shrouded for mourning. We don't know why the young Prudence Punderson was pondering her own mortality; a few years later she married, and then died at the age of twenty-six. Her haunting image may be the earliest self-portrait by an American woman artist.

Although thousands of schoolgirls became accomplished needlewomen, not all liked this work and not all were good at it. One Maryland girl embroidered into her sampler the sentiment "Patty Polk did this and she hated every stitch she did in it. She loves to read much more." Other girls' embroideries celebrated their love of learning in a more elegant fashion. Fifteen-year-old Maria Crowninshield embroidered an allegorical image of female education (p. 134) while a student at the Ladies' Academy, in Dorchester, Massachusetts, which she enthusiastically described as a" delightful mansion of happiness." Following neoclassical style, the picture represents a classical temple, in which a young girl in flowing robes reads from a book held by her teacher, while a goddess crowns her with a wreath.

The propriety of education for women was hotly debated at the beginning of the nineteenth century. It is noteworthy that in this image, the book from which the pupil reads is the English writer Hannah More's Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education, published in 1799. In her popular book, this moderate educational reformer urged that better education would make women better mothers and educators of the next generation of male citizens. Her more radical colleague, Mary Wollstonecraft, in Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), argued that women could be the intellectual equals of men if properly trained. Wollstonecraft was widely read (and often pilloried) in educated households in post-Revolutionary America. These British writers scorned "female accomplishments" as trivial; they believed that young women's minds should be sharpened by exposure to the same subjects studied by young men. Wollstonecraft argued that needlework constricted female minds 'by confining their thoughts to their persons." Yet Maria Crowninshield deftly and mutely turned her talents in female accomplishments to a quietly subversive end: arguing through her stitching that female education is a lofty and worthy goal, fitting with the neoclassical aspirations of the new republic.