5.3: Painting in the New Nation

- Page ID

- 232304

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The challenge facing artists in the early years of the republic was daunting. They needed to justify their art to a nation with little direct exposure to the fine arts. This meant thinking about art in a new way: trying to understand how the arts in a democracy differed from those produced under monarchy. It also meant finding new sources of patronage in a world where the traditional patrons of art notably church and aristocracy-played much-diminished roles. Artists needed to understand who their audiences were: those educated classes knowledgeable about the arts, or the larger but untutored world of ordinary citizens? Four artists- Gilbert Stuart, Charles Willson Peale, John Vanderlyn, and Washington Allston-supply four answers to the question of patronage in a democracy and illustrate the transformation that occurred over the course of the early national period, as art shifted from the expression of civic ideals to a new emphasis on sentiment and feelings.

Portraiture and Commercial Life: Gilbert Stuart

In the half century between winning independence (1783) and the election to the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1828), there was only one sure way for a painter to support himself by his art: portraiture. As before (see Chapters 3 and 4), Americans preferred portraits: images of themselves and their families that they valued both as keepsakes and as ways of recording family lineages. Gilbert Stuart, whose portrait of George Washington we have already examined (see fig. 5.6), was the preeminent American portraitist of the early national period. A former pupil of Benjamin West, he was also an accomplished conversationalist and an extravagant dresser, who spent large portions of his life eluding creditors.

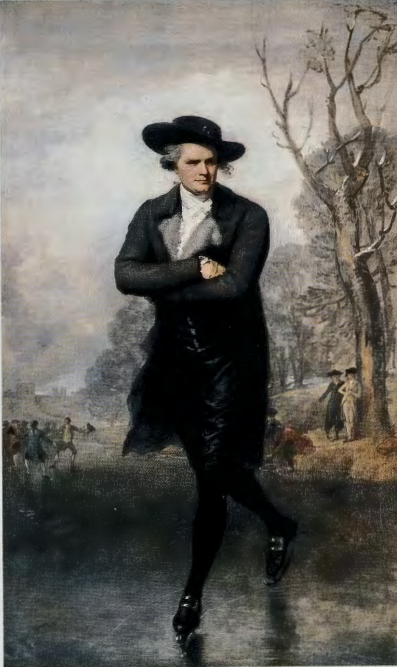

THE SKATER. In 1782, while working in London, Stuart persuaded William Grant, a Scottish gentleman who had commissioned a full-length portrait, to pose on ice skates. The result was The Skater (fig. 5.31). Although Stuart later spun many tales around the event-among them that Grant had to hold on to Stuart's coattails while Stuart skated gracefully across London's Serpentine pond in Hyde Park-he produced an image that won instant acclaim when shown at the Royal Academy's exhibition that year. The painting counterpoints its dominant grays and blacks against small areas of bright color: the flushed pink of Grant's face, the occasional reds of skaters in the background, and even a few spots of red on the background tree. Stuart's contemporaries described The Skater as simultaneously "reposed" and "animated," a union of character traits that indicated-according to the standards of the day-an inner strength independent of birth or class.

The cultural historian Jay Fliegelman has interpreted the painting politically He notes that Grant's poise is possible only for a skater in motion. Were Grant actually standing still, he would topple over. For Fliegelman, this image of balance-in-motion suggests a new and nonaristocratic model of citizenship. Stuart seems to embrace motion as the condition of life. Unlike more aristocratic images, which tend to present a fixed and unchanging vision of the social order, Stuart's portrait of Grant depicts stability in the very midst of change. Stuart's painting represents the worldview of a mercantile society. His skater balances character with motion, self-assurance with worldliness, and independence with community (those figures behind him). He embodies virtues crucial to the success of a commercial republic.

Painting and Citizenship: Charles Willson Peale

For Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), a Philadelphia painter and naturalist, the future of the arts depended on the ability of artists to place their work in the service of the nation. Peale sought to instruct the viewer in values that increasingly came to be thought of as particularly American. This instruction in good citizenship, in turn, helped justify the arts as a vital part of a democratic society. Peale hoped to persuade-or badger-the government into supporting the arts by providing commissions for works that displayed the principles central to a democratic culture.

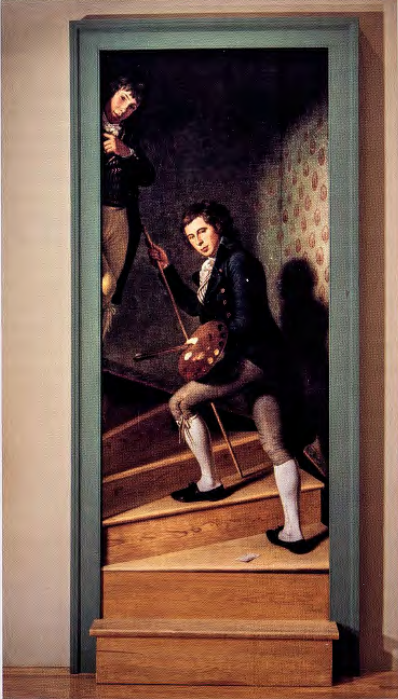

THE STAIRCASE GROUP. In 1795, at the first group exhibition ever held in the United States of works by American artists, Peale displayed a painting now called The Staircase Group (fig. 5.32 and p. 132). Peale termed his life-size work a "deception." It featured his eldest son, Raphaelle, ascending a winding staircase with Titian Ramsay Peale, a younger brother, looking down from the bend above. To heighten the illusionism of the painting, Peale installed it within a door frame, complete with an actual stair step and riser at the base of the painting. The effect was electrifying. When George Washington visited Peale's Philadelphia Museum two years later (see fig. 5.33), he saw the reinstalled painting, and, according to a report by Peale's son Rembrandt, "bowed politely to the painted figures." So powerful was Peale's illusionism that Washington had mistaken Peale's figures for living persons.

Peale directs his painting toward two types of potential audiences: sophisticated viewers who already value art and untutored viewers who do not. The Staircase Group makes no special demands on its viewer; it requires no prior knowledge of the history of art. Instead, it attempts to seduce the eye through playfulness and optical vitality, deceiving the eye so completely that the work of art can be mistaken for the world it represents. Peale's remarkable verisimilitude is thus an advertisement for the sheer pleasure of looking at paintings.

It is also part of what the art historian David Steinberg has called Peale's "project of cultivating a public for high art." Despite its illusionism, The Staircase Group possesses meanings that extend beyond its realistic style. Raphaelle's progress along the stairwell with his palette and maulstick suggests that not just he, but the arts themselves, are ascending. The painting links cultural endeavor with national progress in a theme of uplift and ascent.

This association between art and nationhood was reinforced by the very place in which Peale's deception was exhibited: the former Senate Chamber of Independence Hall, in Philadelphia. Peale was a tireless advocate for a system of federal support for the arts. The Staircase Group fosters support not only of the government, but by it. Both pleasurable and practical, art stands as a testament to the nation's cultural health. It creates good citizens.

THE ARTIST IN HIS MUSEUM. Several years earlier, in 1786, Peale had converted his collection of preserved animals together with his portrait busts of illustrious Americans into a museum, the first natural history museum in America. His goal was "to bring into one view a world in miniature." Situated on the second floor of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Peale's Museum included more than ninety species of mammal, seven hundred bird specimens, and four thousand species of insects. Labels were printed in Latin, French, and English. The birds were displayed in glass-fronted cases with painted backdrops portraying their natural habitats. Most species were classified according to the recently established Linnaean system of taxonomy.

Unlike other museums opened in the eighteenth century-the British Museum opened in 1759, the Louvre in 1793- Peale's Museum was not directed primarily toward the elite. His goal was to provide access to as wide an audience as possible, to introduce what the scholar Edgar P. Richardson has termed "the ideal of rational pleasure," to instruct and entertain. In so doing, Peale sought two results: the creation of an enlightened citizenry and the demonstration that all social order derived from universal principles of nature. The "great book of nature," he wrote, "may be opened and studied, leaf by leaf, and a knowledge gained of the character which the great Creator has stamped on each being."4 For Peale, the Museum was a logical extension of his lifelong commitment to republican forms of government founded on the principles of nature.

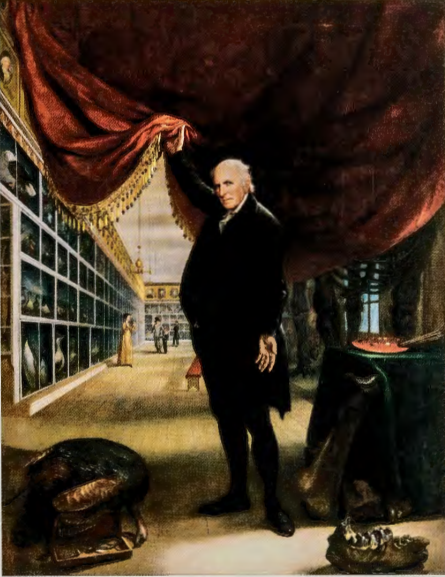

The Artist in his Museum (1822), painted when Peale was eighty-one, reflects his vision of a harmoniously ordered cosmos (fig. 5.33). The painting not only repeats the general layout of Peale's Museum (slightly changed for the sake of visual coherence); it also embodies Peale's own values and dramatizes his point of view. To move into the painting's visual world is, in effect, to step into the mind of Charles Willson Peale and to experience, with him, a particular vision of the American past and future.

The trick lies in how we enter the painting. To proceed, we first pass under the fictional red curtain held aloft by Peale himself. What we encounter is Peale's version of American history. Above us to the left sits a bald eagle, while below it in the foreground, a turkey lies draped over a box of taxidermy tools. These two birds, framing the painting's left side, had earlier been the center of a political debate over which to choose for the "national bird." Franklin had advocated the turkey, a native bird associated with industriousness and humility. He disliked the eagle for its historical associations with imperial European power. Memories of the debate linger in Peale's juxtaposition of both birds at the entrance to the Long Room of his Museum.

The objects in front of Peale-turkey, taxidermy tools, mastodon bones- have not yet been assembled and mounted. They await the efforts of the artist, or, if we are to accept his beckoning left hand, the viewer, who is not only invited into the Museum but asked to join in its tasks. The foreground of The Artist in his Museum thus occupies the world of Peale in the present and anticipates work to be performed in the future. By contrast, the background of the painting-the area behind the red curtain-embodies the past. Unlike the foreground, its world is sealed: the creatures sit stuffed in their display cases, the portraits of prominent Americans hang fixed in their frames. What we encounter on the other side of the curtain is not just a museum, but Peale's visual shrine to Enlightenment values.

We see those values at work in the rows of symmetrical displays, and the perspectival system of the painting itself. Peale's long orthogonals unite the foreground and background of the canvas in a single visual sweep. The Artist in His Museum thus exhibits more than specimens and portraits. It teaches the viewer about nature's underlying rationality, and it transforms the American Revolution, present through the portrait busts that line the Museum's walls, into a triumph of Enlightenment principles.

Peale's clothing similarly reflects national concerns. His knee breeches identify the artist as a member of the Revolutionary generation and contrast with the trousers of the man and boy in the background. This contrast in fashion highlights Peale's unique role as a chronicler of the American Revolution-someone who not only participated in its events, but who now instructs the viewer in its lessons. The grandfatherly figure of Charles Willson Peale invites us to continue the Revolution that his generation began.

Myth and Eroticism: John Vanderlyn

While Charles Willson Peale attempted to instruct the public in the virtues of good citizenship, turning the viewer's thoughts from "sensuality and luxury" to good citizenship and the pleasures of the intellect, John Vanderlyn (1755-1852) veered in the opposite direction. Vanderlyn's career mirrors the larger shift in the early national period from a culture of "republican virtue" to one increasingly occupied with private pleasures.

ARIADNE ASLEEP ON THE ISLE OF NAXOS. In Ariadne Asleep on the Isle of Naxos (1809-1812), Vanderlyn drew on Venetian traditions of the nude to portray a woman from mythology abandoned by her lover (fig. 5.34). Ariadne, however, reaches beyond the grace and beauty of its Renaissance style to appeal to less refined sentiments. The painting offers an eroticized spectacle that flies in the face of the decorum and restraint expected of neoclassical art.

Vanderlyn's American viewers were scandalized. They were unprepared for a nude female figure dominating a lush landscape. Vanderlyn himself had anticipated this response. In a letter written in 1809, he observed that the "subject may not be chaste enough for the more chaste and modest Americans, at least to be displayed in the house of any private individual, to either the company of the parlor or drawing room, but on that account it may attract a greater crowd if exhibited publickly [sic]." Vanderlyn believed that he would draw large crowds to his painting precisely because of the controversy it was likely to cause.

At one level, Ariadne embodies European traditions of high art. Ariadne's creamy; voluptuous body derives from Italian precedents, linking Vanderlyn-and by association, American art itself-not only with the classical past, but with a cosmopolitan, transatlantic culture of refined taste. From this point of view, Ariadne was Vanderlyn's way of showing that American art was not provincial. On the contrary, American painters could match anything Europe had produced.

At another level, Ariadne represents nature itself: innocent, unguarded, and voluptuous. She can be understood as an allegory of the American landscape. In her recumbent posture, she is as exposed and inviting as the New World, and like it, she invites conquest. Painted in the years immediately following the Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark expedition (both achievements of the Jefferson administration), Vanderlyn's painting translates continental expansion into a discourse on female availability.

But Ariadne also offers veiled eroticism. Ariadne's lover, Theseus, disappears in the distant background, where he is about to join his ships and embark for Athens. With Theseus's disappearance, the viewer is free to attend to the painting outside its mythic narrative. Despite its classical framework, the canvas's emotional charge lies elsewhere: in the realm of the viewer's unacknowledged desires. Although Ariadne's style derives from high European art, the painting's affect-its emotional jolt-appeals to a world of private tastes and hidden pleasures.

Ariadne begins, then, where Peale leaves off. It offers a not-so-chaste vision of nature grounded less in rational principles than in a more subterranean realm of feeling and desire. Vanderlyn shifts the inner logic of painting from moral and civic uplift-the idea that art instructs its viewer-to something we recognize more familiarly today from advertising and television: images charged with an erotic undercurrent. Where Peale takes the "high road," Vanderlyn swerves down the low, dressing up desire in the language of classical taste.

Early Romanticism: Washington Allston

Washington Allston (1779-1843), Vanderlyn's friend and younger contemporary, carries the notion of the private one step further. A native of South Carolina, Allston graduated from Harvard College in 1800 and soon departed for Europe, where he settled in London and studied with Benjamin West at the Royal Academy. He returned permanently to Boston, after further travel, in 1818. An avid reader of gothic novels (he would later write one himself), Allston was shaped by the currents of romanticism swirling through Europe. While visiting Italy in 1804, he befriended the British poet and essayist Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Allston learned from Coleridge and his circle of friends the central tenets of romantic thought: a mistrust of rationality; a preference for intuition; an emphasis on heightened states of emotion; a faith in the high calling of the poet and painter; and a deep skepticism about society as anything more than a corruption of individual innocence.

Romanticism viewed the world as a breathing organism. Matter was not merely matter, but was always animated by a larger, living force. This idea of a "universal intellect," lending vitality equally to people and inanimate objects, marked the end of an older, more rationalistic sensibility. Intuition, rather than reason, provided the most truthful access to the world. An older emphasis on proper conduct and good behavior gave way to new emphases on emotions and the inner life. Allston's deepening romanticism isolated him increasingly from his Boston patrons. His vision of art as an expression of an "ideal world" left little room for their commerce and profit.

ELIJAH IN THE DESERT. In 1817- 18, Allston painted Elijah in the Desert, a work that was greeted by Boston's cultural elite with equal amounts of indifference and hostility (fig. 5.35). Allston's monumentally sized canvas (4 by 6 feet) brings the ambitions of history painting to the newly emergent genre of landscape (see Chapter 8). Although it derives its story from the Bible, and thus qualifies as a suitable subject for history painting, its spaces are devoid of social forms. There are no cities, no gatherings of people, no signs of classical order to link the frail prophet in the foreground with a larger realm of civic endeavor. On the contrary, the downcast posture of Elijah suggests that his voyage is an internal one, a private affair defined by introspection and imagination, rather than reason. The prophet becomes a type of the romantic genius: isolated from society, inspired by nature (Elijah is being fed by ravens), and reliant on his imagination to bridge the gap between the barrenness of the world he inhabits and the promises of the ideal realm he seeks.

Allston's painting technique reinforces his romantic concerns. In Elijah in the Desert, he abandons the classical tradition, with its emphasis on clearly outlined figures and color bounded by form, in order to work with impastoed surfaces and rich glazes. He lays his paint on with a loaded brush and then applies layers of translucent varnishes, each tinged with a slightly different color. The result is a surface that vibrates with light, each element in the composition joined seamlessly to ~he others. This emphasis on atmosphere and texture encourages the viewer to approach Allston's painting empathetically.

No·wonder, then, that the painting's first Boston viewers expressed surprise. They sensed, correctly, that Elijah in the Desert represented a profound challenge to their world. Its apocalyptic undertones, its focus on what the art historian David Bjelajac has called "solitary meditation," its indifference to social custom all threatened their faith in reason and society.

MOONLIT LANDSCAPE (MOONLIGHT). In Moonlit Landscape (Moonlight) (1819), Allston offers a night scene more magical than real (fig. 5.36), choosing mood over reason, color over line, moon over sun. Painted soon after his return to Boston, the canvas is filled with imagery of travel, as if its figures were on a quest that we, as viewers, can only imagine. The foreground individuals appear to be at the beginning-or end-of a voyage. The boats and bridge and the curving river all suggest motion and change. The youth walking at the edge of the river carries a staff in his hand, the emblem of the traveler. Yet despite these hints of a story, the painting remains a mystery. The art historian Marcia Wallace has interpreted the Moonlit Landscape as a moment when Allston's past and present coalesce. The background hills and mountain recall his life in Italy, while the foreground figures, bathed in moonlight, echo Allston's description of the October night he arrived in Boston harbor, when the "moon looked down upon us like a living thing, as if to bid us welcome." The cropped shadows of the foreground figures, together with the ribbon of light running under the bridge, owe their visual power to the moon, which brings together sky and earth, background and foreground, past and present.

Moonlit Landscape announces a new type of painting in the United States. What matters to Allston is feeling and sentiment, as if the viewer were beholding an inner landscape, a space more psychological than real. By mixing memory with magic, and hinting at meanings it will not reveal, Moonlit Landscape transforms painting from an exercise in civic values (Stuart and Peale), or a retreat into erotic fantasy (Vanderlyn), to a form of private reverie. The painting carries the viewer away from social life and public issues to a realm defined by poetry, mood, and suggestion.