5.1: The American Revolution in Print, Paint, and Action

- Page ID

- 232302

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)With the close of the French and Indian War in 1763, writers on both sides of the Atlantic had begun to imagine the American colonies as the future birthplace of a great civilization. A Connecticut minister, Ezra Stiles, exulted, "Not only science, but the elegant Arts are introducing apace, and in a few years we shall have . . . Painting, Sculpture, Statuary . . . in considerable Perfection among us." Colonial leaders increasingly viewed North America as the home for a new art surpassing the achievements of the Old World.

There was a problem, though. The American colonies were not independent. They were part of someone else's empire, and the rules of empire were clear: colonies served their mother country's needs. British colonies were to provide raw materials for British manufacturing and a market for British goods-not to compete with the mother country commercially or develop their own manufactured goods. In this self-centered arrangement, Britain measured the health of the empire by taking her own pulse. What happened in the colonies was of little concern, so long as London prospered.

This indifference inflamed American grievances. The British laws that infuriated American colonists and eventually provoked rebellion,-the Stamp Act (1765), the Townshend Act (1767), and the Tea Tax (1773)-were intended to subordinate the colonies to British imperial needs. By imposing taxes and customs duties on its American colonies, Parliament hoped to pay for its debts from the French and Indian War (1754-1763). In the game of empire, Parliament was playing by the rules; the American colonials were not. They resented what they perceived as the erosion of their rights as Englishmen, and they responded by banding together to boycott British goods.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, colonial America surpassed Great Britain in size, population growth, and standard of living. Ben Franklin wondered out loud why the American colonies-with their unlimited resources and vast commercial potential-had not yet overtaken England in the arts. "Why should that petty Island [England] which compar'd to America is but like a stepping Stone in a Brook, scarce enough of it above Water to keep one's shoes dry; why, I say, should that little Island, enjoy in almost every Neighbourhood, more sensible, elegant and virtuous Minds, than we can collect in ranging rno Leagues of our vast Forests?" Franklin believed that America's time would soon come. He consoled himself with the belief that "the Arts delight to travel Westward." 1

Americans imagined their independence through the metaphor of a child growing up. They saw themselves as Britain's loyal offspring and believed that they had outgrown their childhood. They began to think of Britain as an "unnatural" mother who stifled her offspring's need for independence. This vision of Britain as an unnatural parent animated the rhetoric of the colonies in the years before the Revolution. In newspapers, cartoons, prints, and broadsides, the colonists portrayed themselves as the innocent victims of British willfulness. They turned to print culture to help shape a nascent American identity.

Print Wars

In an era before computers and television, the printed page rivaled word-of-mouth as the main medium of information. Prints were rapidly produced and quickly circulated. Most popular prints of the eighteenth century were created by incising lines on a metal plate, either by etching, in which the lines are cut by acid, or by engraving, in which the lines are cut by hand, using special engraving tools. Printers could pull many copies from one plate, which allowed them to sell the prints to large numbers of people. Hawked on the street, sold in bookshops, or offered through advanced subscriptions, prints ranged in price and quality. Like newspaper cartoons today, they frequently satirized political events, public controversies, and local fashions. Often witty and biting in tone, they sought to influence opinion and mobilize support. Frequently prints combined images with text, which appealed to an increasingly literate audience eager to discuss the issues of the day. Eighteenth-century print culture flourished on both sides of the Atlantic. Often fostering modern notions of individual rights, prints played a vital role in transforming politics from a pastime of the elite to a concern of all classes.

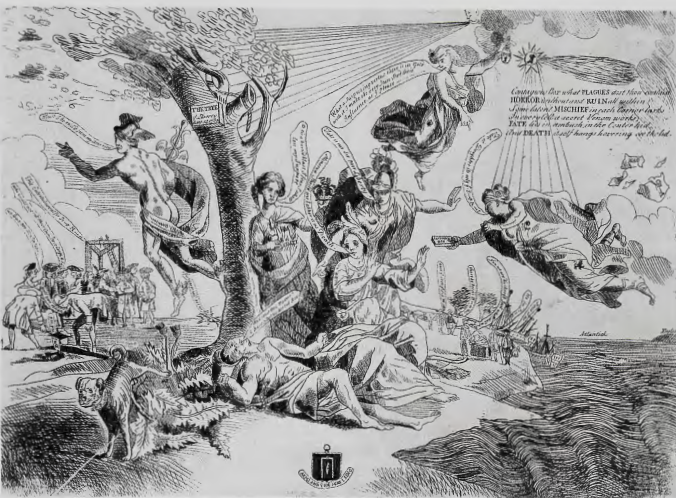

THE DEPLORABLE STATE OF AMERICA. The Stamp Act of 1765, enacted by Parliament without the consent of the North American colonies, imposed a new tax on paper products to help pay for the French and Indian War. John Singleton Copley (see Chapter 4) responded to the Stamp Act by re-engraving a political cartoon that had appeared previously in England. In The Deplorable State of America, 1765, Copley personifies England as a winged woman who hovers over the Atlantic Ocean while offering Pandora's box to the inhabitants of America (fig. 5.1). England says to her "daughter," America, "Take it Daughter its only a S- A- [Stamp Act]." America is portrayed as an Indian with feathers in her cap. She raises both hands in protest and cries out to the helmeted figure behind her, "Minerva shield me I abhor it as Death." Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, warns in turn, "Take it not for poor Liberty." Behind England float the fragments of the Magna Carta, the basis for British civil liberties, now torn up and discarded. A Liberty Tree stands at the center of the image (most American towns now had a tree designated as a meeting place for Patriots and called the tree by this name). At its foot a supine Indian, another representative of America, cries out, ''.And canst thou Mother! And have pity this horrid box" - a reference not only to Pandora but also to the larger perversion of mother-child relations, which defines the colonies' unhealthy ties to Britain.

The gallows in the background stands ready to hang offending stampmasters, while the dog in the left foreground urinates on a Scottish thistle. The dog belongs to the member of Parliament William Pitt (the Elder), a strong supporter of American independence. The thistle stands for Lord Bute, whom i:olonialists reviled as a staunch proponent of taxation. A rattlesnake, emblem of American freedom, glides out from under the thistle. During the French and Indian War of the previous decade, Benjamin Franklin had printed a widely distributed image of a snake divided into segments. The accompanying words, "JOIN, or DIE," urged the American colonies to defend themselves and their freedoms by uniting into a single body.

Copley's print links references to classical mythology and British history with symbols tied to particular people and causes (Lord Bute and the thistle; the rattlesnake and American freedom). The viewer is assumed to be sufficiently well informed to catch the references and synthesize them. In this way, the print is as much read as viewed.

THE BLOODY MASSACRE. Five years later, in 1770, Paul Revere published a print commemorating the killing of some Bostonians by British soldiers that year and portraying the event as a slaughter of the innocents. Revere's print, The Bloody Massacre, was plagiarized from a drawing by Copley's step-brother Henry Pelham. The print circulated widely in the weeks after British soldiers, quartered in Boston, had opened fire on a hostile crowd of local workers (fig. 5.2). Revere depicts the British redcoats as an organized war machine. They stand under a fictitious sign proclaiming "Butcher's Hall." The soldiers' left legs all face forward; their bodies form a sharp diagonal, slicing into space; their muskets almost touch the unarmed Bostonians facing them; and their coordinated gunfire produces clouds of smoke, converting the square into a smoldering inferno.

The Americans, by contrast, stand or slump in disarray. Two lie wounded on the ground, while a third falls into the arms of a companion in a pose recalling Christ's deposition from the Cross. The massacre occurs against the background of Boston landmarks (the Old State House-called the Towne House during the colonial period- and the steeple of the First Church), a visual emphasis designed to inflame locals already sensitive to the British occupation of Boston. Revere's print distorts the historical recordwhich suggests that the colonists deliberately provoked British troops-for the sake of propaganda. Initially, many Bostonians were wary of those who participated in the "Massacre" and assumed that the motley crowd of Irish Catholics, African Americans, and European Americans was a mob run amok. Revere's print helped galvanize anti-British sentiment by recasting the mob as victims of British aggression.

"PLAYING INDIAN." No one was better at inflaming local feelings than Samuel Adams, the silver-tongued Boston radical. When the Sons of Liberty-an alliance of colonists eager to contest British policies-failed to persuade the captains of ships in Boston harbor to return their cargo of tea unopened to England, as a protest against the tax levied on it, Adams told a concerned gathering at the Old South Meeting House that they "could do nothing more to preserve the liberties of America." His phrase was probably a signal. No sooner were the words said than "Indian" war whoops issued from the street. A group of men disguised as Mohawk Indians dashed to the harbor and boarded the ship Dartmouth. They systematically dumped 342 chests of tea into the harbor, an event that we now call the Boston Tea Party.

By dressing as Indians, the colonists created a form of street theater that captured two different ways of imagining themselves. The first mode, illustrated in a print published in London Magazine in 1774, represents America as a vulnerable Indian princess (fig. 5.3). With her breasts bared, her skirt lifted, and her arms and legs pinioned by others, America lies vulnerable to British assault. Yet as Lord North (the prime minister) force-feeds the Indian princess tea, she fights back, spewing hot liquid into his face. This indelicate act highlights the second role that the colonists played by dressing as Indians. They asserted themselves as agents of resistance: "savage" in their innocence and independence.

The cultural historian Philip DeLoria has noted that American identity-from the Boston Tea Party to the present-has been inextricably bound to Native American identity. By "playing Indian," the colonists were doing more than transforming Native cultures into a handy symbol for New World life. To play Indian was to be a revolutionary. Indians n;presented many things to the colonists: innocence, savagery, nature, North America itself. For the colonists, playing Indian meant trying on a new self and embracing the revolutionary possibilities of the New World.

Festivals and Parades

PRINTS PROVIDED ONE WAY for Americans to mobilize opposition and identify as a community. A second way lay in the older tradition of street theater: festivals and parades, which helped the colonists identify themselves as American citizens, rather than British subjects. By bringing together different classes, trades, and groups, these parades helped unite the new nation across traditional · boundaries. After independence, the spectacle of the parade proclaimed that a// had participated in the Revolution and that all were entitled to its fruits. Parades also kept the past alive. They allowed the Revolution to be remembered and reinterpreted year after year. Fourth of July parades, banners, bonfires, and other ceremonial activities permitted the new nation, as historian David Waldstreicher has phrased it, to celebrate its own origins in repeated "rites of assent."

During the struggle for independence, there were mock funeral marches for King George 111, theatrical performances, and military reenactments. In 1779, the Boston militia staged a "mock engagement" before a "vast concourse of spectators," followed by a meal for one hundred patriots under a tent on the Boston Commons. The purpose of these events was not entertainment, but nation building. These "rites of assent" allowed people across a wide spectrum of classes to affirm,their collective identity as Americans. People had been used to thinking of themselves in terms of their local affiliations. Now, in addition to their local or regional identities, the former colonists began to view themselves as cit_izens of a new nation.

Reinterpreting the Revolution: John Trumbull

John Trumbull (1756-1843)-the son of a former governor of Connecticut-served briefly as a mapmaker in the Continental Army. After the war, Trumbull sought to mythologize the Revolution in a series of celebratory paintings. Beginning in 1786, and continuing for the next thirtyfive years, he created a cycle of revolutionary paintings that lifted the war out of history and into the realm of legend. His goal, as he explained in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, was to transform painting from a "frivolous" trade, "little useful to society," into a form of cultural memory. Trumbull wished to give the "future sons of oppression and misfortune, such glorious lessons of their rights, and of the spirit with which they should assert and support them," that mankind would never forget one of its greatest moments. Trumbull also hoped to turn a profit by exhibiting the paintings to paying audiences and by selling prints engraved from the series to subscribers. In painting the events of the American Revolution, Trumbull brought together his feelings of patriotism, his ambitions as a painter, his desire to place art in the service of the new nation, and his need for income. He failed in this last ambition: neither Trumbull's paintings nor the prints based upon them captured the audience or the profit Trumbull hoped for.

At the time that Trumbull began the series, the nation was in turmoil. The system established by the Articles of Confederation (1781), which loosely bound the colonies together in the years after the Revolution, was in a state of collapse. To replace it, a new Constitution was drafted in 1787, proposing a strong central, or federal, government. This quickly divided Americans into two bitterly opposed camps, the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists. The Constitution was finally ratified by the required majority of states (nine) in 1788 and so came into effect that year; but the arguments continued.

Other issues, too, divided Americans. Social changes engendered by the Revolution-the enfranchisement of ever-greater numbers of white males, the breakdown of traditional forms of deference among social classes, and the general weakening of class authority-were proving to be more radical and egalitarian than some leaders had bargained for. Conservative figures such as Trumbull sought to slow the Revolution's tendencies toward social leveling. Where Revere's Bloody Massacre had earlier inflamed colonial passions by pitting Patriot against Loyalist, Trumbull's paintings two decades later sought to reconcile the former antagonists in a transatlantic alliance of shared civic values.

THE DEATH OF GENERAL WARREN AT THE BATTLE OF BUNKER'S HILL, 17 JUNE, 1775. Trumbull painted the first canvas of the series, The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill, 17June, 1775, while he was a student in the London studio of Benjamin West (fig. 5.4). The battle, which Trumbull had witnessed through field glasses from a distance, allowed both sides to claim victory. Although the British officially won the battle, they suffered severe losses: 1,150 men killed-almost three times the casualties suffered by the Americans. Trumbull's painting depicts the fatalities of both sides' commanding officers: American General Joseph Warren, shot in the head, dies in the arms of a comrade, while the British Major John Pitcairn, similarly wounded, collapses below a British flag into the arms of his son.

Trumbull drew on precedents such as Benjamin West's The Death of General Wolfe (see fig. 4.34) for this painting, but he transforms West's relatively static and neoclassical composition with the introduction of emotionally charged diagonal wedges. Through dramatic contrasts of light and dark, Trumbull emphasizes the alarm of his subjects at a moment of great intensity. As General Warren, clad in white, lies dying, a British grenadier-above him and to the right-prepares to stab him, in effect killing him a second time. A British officer stays the grenadier's bayonet, while the kn·eeling American who cradles Warren likewise extends an arm to fend off his thrust. The two officers, one British and one American, are linked by a shared code of honor. The.painting highlights the death of a gentleman in a patriotic cause, contrasting his sacrifice with the mean thoughtlessness of the grenadier. The officers' coolheaded restraint of the hasty grenadier symbolizes aristocratic mastery over impulse and irrationality. The lesson: even when encountered as enemies, true gentlemen value honor and duty above all else.

Such lessons were especially timely for Trumbull in 1786. This was the year of Shay's Rebellion, when a group of debt-ridden Massachusetts farmers took up arms against the state government. Although the rebellion was ultimately subdued, it left Federalist figures like Trumbull profoundly alarmed at the unworthy behavior of the commonality. Trumbull's painting reconstructs the Battle of Bunker Hill ( as it is now called) as a moment of upper-class solidarity. To an elite audience in 1786, this portrayal of revolution in terms of social stability must have felt reassuring Two black figures appear in Trumbull's painting: a slave - who stands loyally behind.his master in the painting's lower right corner, and a black man whose face only is visible in the crowded group of figures at the left edge of the painting. A contemporary observer of the battle credited Peter Salem, a former slave, with the killing of the British Major Pitcairn: 'i\mong the foremost of the leaders was the gallant Major Pitcairn, who exultantly cried 'the day is ours,' when Salem, a black soldier, and a number of others, shot him through and he died." 2 Although it is unclear whether the black man in Trumbull's painting is Salem, it is quite clear that he is disallowed any real role in the battle. His musket points up and away from the fighting, and his posture signals subservience rather than bravery. Over the course of the American Revolution, more than five thousand African Americans fought against the British. Several blacks fought at Bunker Hill, and one performed heroically enough for his commander to honor him as "an experienced officer as well as an excellent soldier." Many of the free and enslaved blacks who joined the American forces were put to work as agricultural or construction workers, because their commanders were reluctant to arm them.

Trumbull's attention to black-white relations in The Death of General Warren stands in marked contrast to West's earlier focus on Native Americans in The Death of General Wolfe. By 1786, white Americans felt increasingly confident that North America belonged to them as a birthright. Where West depicted the French and Indian War of the 1760s as an alliance between Native Americans and colonists (in fact, both sides included large numbers of Indian combatants), Trumbull shifts the focus two decades later to African Americans. This transfer of attention suggests how much American independence brought blackwhite relations to the fore. It also reveals the racial anxieties that Trumbull shared with many of his colleagues. Trumbull subordinates his African American figures to their white commanders.

Trumbull's decision to portray an armed black man as a faithful servant reflects the reluctance of white Americans to view Africans outside their traditional roles. In mythologizing the Revolution, Trumbull focuses on its promise of social stability rather than its more egalitarian possibilities. Though his interest lies in American independence, he seems unable to imagine a wholesale rethinking of class or racial relations. His goal instead is to preserve a vision of civic order congenial to the beliefs of the governing classes.

Celebrating Franklin and Washington

Not all commemorative images of the Revolution focused on historic moments or scenes of battle. Portraits of revolutionary heroes-Washington, Franklin, Jefferson-proved immensely popular. In fact, the demand for such images was so great that an entire industry arose to satisfy it. Benjamin Franklin developed into an international celebrity.

FRANKLIN AS EXPERIMENTALIST. In 1789, only months before Franklin's death, the American Philosophical Society commissioned Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) to record Franklin's likeness. Peale produced a portrait that focuses on Franklin's appeal to the "common man" (fig. 5.5). The seated Franklin is shown against a lightning bolt in the background, an allusion to his famous experiments with electricity. Franklin's appearance is down-to-earth. His character is conveyed by his abstracted gaze, his calm demeanor, and his bifocals (with whose invention he is generally credited). He is a thinker. The writing implements at his hand remind us that Franklin's work is conducted within the realm of learning, science, and letters. The manuscript page in front of him contains a quotation from his book Experiments and Observations (1751), about the success or failure of lightning rods. Franklin holds a lightning rod with a pointed tip in his left hand, while a second lightning rod with a rounded tip lies unused on the table before him The lightning rods here allude to politics as much as to science. The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge had once asked Franklin to serve on a committee to investigate the safest way to protect armories loaded with gunpowder from lighting hits. Franklin's fellow committeeman Benjamin Wilson recommended round-tipped lightning rods, on the grounds that they attract fewer lightning bolts. Franklin objected, advocating pointed rods as less dangerous, while noting that rounded "knobs" draw lightning at "greater distances."

The controversy soon escalated from lightning rods to politics. King George Ill sided with Wilson against Franklin. The king's decision not only infuriated Franklin but cast the debate as a contest between British and American ways of doing things. Peale's painting includes both types of rods. By placing the diagonally elevated pointed rod in Franklin's hands and leaving the knobbed rod on the table, Peale draws attention to the nascent nationalism of Franklin's leadership. His science goes hand in hand with his patriotism.

So, too, for the blue banyan that Franklin wears. A casual item of dress originally imported from India and designed for private wear in the home, the banyan suggested the leisurely nature of scholarly pursuit and the capacity of calm men to remain undistracted by outside pressures in the quiet of their studies. Men like Franklin investigate· the world- and ultimately govern it-with no interest in mind other than the public good.

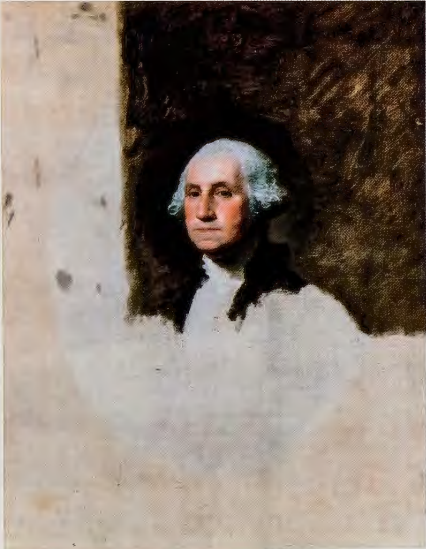

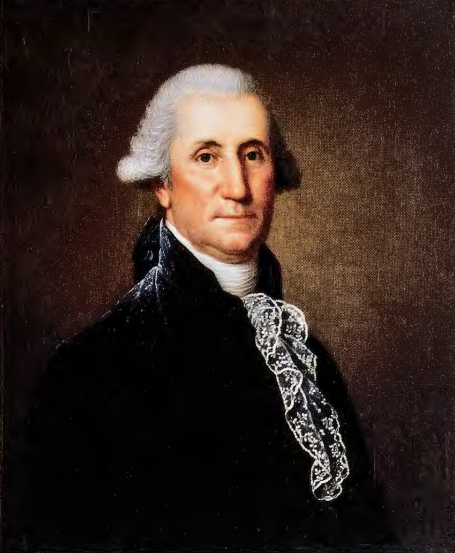

THE "ATHENAEUM PORTRAIT." The portrait of George Washington painted by Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828) in 1796 is among the most celebrated of American images (fig. 5.6). Known as the "Athenaeum Portrait" because it was acquired by the Boston Athenaeum after Stuart's death, it has been reproduced more frequently and circulated more widely than any other American painting and has done a great deal to define the national memory of Washington.

From its customary position high on the classroom wall, the portrait has stared down reproachfully at generations of misbehaving children, reminding them of the formidable virtues of this Founding Father. But even as it has been used to perpetuate Washington's status as an icon, the painting has also attained a casual familiarity in everyday life. As you read this, in fact, you may well have a few reproductions of the painting in your wallet; Stuart's painting is the source of the image on the one-dollar bill.

The Athenaeum Portrait was only one of dozens for which George Washington posed in his lifetime. Yet today it has become so seemingly natural that we are likely to be shocked by the alien strangeness of other portraits like that by Adolph Wertmüller (1751- 1811), painted about the same time, circa 1794 (fig. 5.7). Despite our sense that the rather dour Washington in Wertmüller' s painting is somehow "wrong," it is interesting to note that Stuart's was not necessarily a faithful likeness. Many competing painters claimed that their portraits were more accurate. One early nineteenth-century writer playfully suggested that if Washington were suddenly to appear to his friends looking as he did in Stuart's portrait, he would have to show his credentials in order to prove his identity.

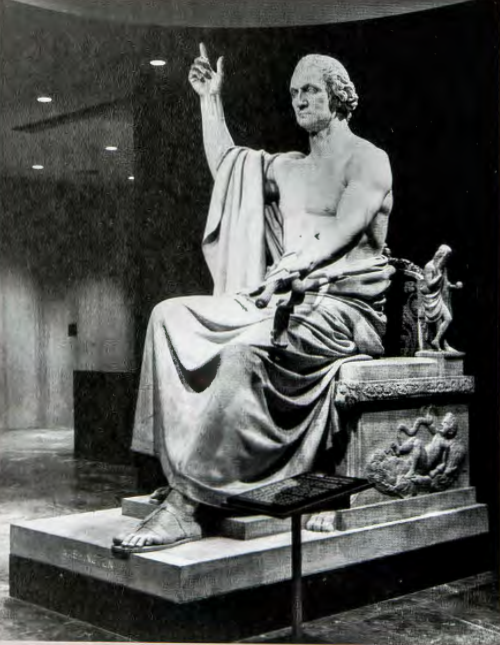

Washington as Zeus

IN 1832, HORATIO GREENOUGH (1805-52), the first American sculptor to study in Italy, was awarded a prestigious commission to sculpt a public statue of George Washington (fig. 5.8). Congress allocated $20,000 for its purchase (a whopping sum at the time). Greenough 's idea was to model Washington on the ancient Greek sculptor Phideas's fifth-century B.C.E. statue of Zeus. Greenough 's statue bears the instantly recognizable visage from Gilbert Stuart's portrait now fitted onto the exposed torso of a muscled superhuman, seated and enthroned. While Washington's right hand points heavenward, his left hand offers his sword to the viewer: twin gestures that link Washington 's authority with his renouncing of monarchial power. Greenough 's statue alludes to the Roman leader Cincinnatus, who was linked to Washington in the public imagination because he refused dictatorial power and retired instead to the quiet life of a private citizen.

Placed in the Rotunda of the Capitol and unveiled to the public in 1841 , Greenough's colossal sculpture was instantly controversial. Supporters admired the "loftiness" of Greenough 's vision, but detractors-and there were many of them-found the statue inaccurate, offensive, even comical. Philip Hone, a New York politician, lambasted it for depicting Washington "undressed, with a napkin lying in his lap." Most Americans simply did not want to see their first president, however heroic, in a state of semi-nudity. The 12-ton statue proved too heavy for the Rotunda; it cracked the floor. Greenough's Washington was moved to the East Front of the Capitol in 1843 and eventually wound up in what is now the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

Stuart had several sittings with Washington (who disliked posing for portraits but endured it nonetheless), before he "pinned" the image that has come down to us. It differed significantly from other portraits. Although Washington, by all accounts, had pale skin, Stuart endowed him with ruddy features, adding vivid touches of red· to Washington's cheeks and nose. He darkened Washington's eyes, rendered his face more compact and less elongated than in other portraits, pursed his lips, and emphasized the aquiline shape of his nose. Stuart's interpretation turned out to be the perfect and necessary formula for expressing Washington's national image. The ruddy skin tones suggested a man of energy and passion, while the stern gaze and taut lips hinted at the discipline and self-control that rendered Washington the master of his own emotions. The slightly downward cast of Washington's stare confirmed the viewer's sense that he was in the presence of a moral giant, but the simplicity and directness of the portrait leavened Washington's godlike power, thus avoiding unsavory comparisons with European monarchs.

Deviating from common practices of depicting rulers (found in some of his own portraits as well), Stuart avoided placing Washington in a grand architectural setting, draping him in ermine, pinning him with sashes and military medals, or surrounding him with objects emblematic of his power and his office. Instead, he focused exclusively on Washington's face. This had several effects. First, it accorded with Washington's reputation for unpretentious candor. Second, by removing him from the realm of everyday life, the portrait achieved a timeless quality. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the close focus on the head enabled the portrait to be readily copied, adapted, and appropriated in a way that a full-length portrait with complicated trappings could not. The face was thus well suited to fill the rapidly growing demand for images of Washington among the adoring American public.

Stuart left the portrait unfinished. Once he had painted the face, he realized that the image would be invaluable as a template from which he could produce multiple copies. Despite repeated pleas for the portrait by Washington's wife, Martha (who had commissioned it), Stuart decided not to finish the painting, so that he could retain possession rather than deliver it to her. He kept it in his studio long after Washington's death, eventually producing sixty oil copies. Unwittingly anticipating the portrait's later function as currency, Stuart took to calling the copies his "hundred dollar bills," since that was what he charged for them.

The African American Enlightenment

At the same time that artists were shaping the American Revolution-visualizing it, justifying it, mythologizing it- African American artists and writers found themselves exploring a different notion of "independence." What might freedom mean to an artist who could rarely participate in popular debates about liberty and justice and had no legal right to his or her own body? During the years of the Revolution a quiet but extraordinary dialogue developed between two gifted African Americans, the poet Phillis Wheatley and the artist Scipio Moorhead.

SCIPIO MOORHEAD'S PORTRAIT OF PHYLLIS WHEATLEY. In what is perhaps the first portrait (1773) produced by an African American of a member of his own race, Moorhead ( c. 1750--?) depicts Phyllis Wheatley, a fellow Bostonian and fellow slave, seated at a writing desk with a quill pen in one hand (fig. 5.9). (The image is unsigned, but scholars generally attribute it to Moorhead.) Wheatley gazes into the distance, as if pausing in the midst of inspiration.

Wheatley ( c. 1753-84) was something of a prodigy. Brought to Boston from Gambia, West Africa, in 1761, while still a young child, she flourished under the tutelage of her mistress, mastering English, Latin, and the Bible. At the age of twenty, Wheatley published the first documented book of poetry by an African American-and thus became a cause célébre in Boston. Her poems and commemorative pieces, reproduced in newspapers throughout New England, served as a test case for European Americans on the question of whether Africans were capable of intellectual as well as manual labor.

The ironies surrounding Wheatley's case are daunting. The generation that justified their own political revolution in the name of reason had a difficult time ascertaining whether reason played any role at all in the lives of black people. In the same years that Thomas Jefferson and the other Founding Fathers were declaring that "liberty" was a universal principle applicable to all people, they also justified slavery as a system rooted in what they believed was the "inferior" moral and intellectual capacity of Africans.

Moorhead's portrait of Wheatley engages those debates. Engraved in 1773 as the frontispiece for her first volume of poetry-a book printed in London after colonial American printers refused to publish it-the image casts Wheatley as a thinker rather than a domestic worker. The image is less a "snapshot" of Wheatley herself than an argument for the intellectual aspirations of African Americans. Moorhead draws upon the same visual formula used by John Singleton Copley in his portrait of Paul Revere (see fig. 4.32), a pairing of head and hands with attributes of the sitter's labor. While Copley's portrait engages issues of class and the social status of the artist, Moorhead's portrait refocuses the debate to take in race and the social status of the slave. Moorhead's image includes no signs of domestic work. Instead, Wheatley's quill connects the page to the brightness of her eyes, hence the brightness of her mind. She is defined not by her employment as a slave but by her attainments as a poet. The image is a salvo in the battle for black rights. Wheatley's attainments as a poet and a pious one at that (her simple cap suggests her modesty)-assert the capabilities of all African Americans: if black people can create culture, if they can master European poetic forms, then they must be accorded the "natural rights" common to all humanity.

Besides suggesting the sitter's propriety (in the modest cap), the engraving hints at an intellectual bond between painter and poet. He portrays her in a moment of inspiration. Moorhead's portrait echoes lines in Wheatley's poem dedicated to him, "To S. M., A Young African Painter, on Seeing His Works": "Still may the painter's and the poet's fire / To aid thy pencil, and thy verse conspire!" Wheatley's poem links the painter and the poet together in a common enterprise. The term "conspire" derives from the Latin root for 'breathing together." It suggests not only that the painter and poet share the same experience as slaves and artists but that they "conspire" together in their labors, each affirming through the other the humanity they both share. Though slaves in their private lives, they 'breathe together" in their art.

LIBERTY DISPLAYING THE ARTS AND SCIENCES BY SAMUEL JENNINGS. Two decades later, when the Free Library of Philadelphia decided to build new premises, it commissioned the Philadelphia painter Samuel Jennings (c. 1755-after 1834) to paint an image of the Goddess of Liberty assisting a group of free blacks "resting on the earth or in some attitude expressive of ease and joy."

Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences (1792) reflects not only the aspirations but also the limitations of progressive abolitionist thought at the close of the eighteenth century (fig. 5.10 ). The painting unfolds as a drama of racial uplift. A figure of Liberty, dressed in contemporary fashion, sits amid objects that represent science and the arts: music, painting, architecture, geography, sculpture, architecture, geometry, astronomy. She cradles a pole with a "liberty cap," an image of freedom dating back to Roman times. Her right hand holds a catalogue of the Free Library, which rests in turn upon volumes labeled ''.Agriculture" and "Philosophy." The broken shackles at her feet symbolize emancipation. The portrait bust in the foreground probably represents Henry Thornton, a prominent abolitionist leader.

Liberty bestows the gifts of Western civilization upon a grateful group of former slaves. The prostrate father and son in the foreground are dressed in Western fashion, while the mother, wearing an African headdress, places her right hand over her heart. In the mythic scene behind them, a group of black figures celebrate by dancing around a Liberty Pole. The masted ships in the background represent Philadelphia's mercantile activities. When seen against the forested and uncultivated background hills, however, they could also allude to the Middle Passage, the route that brought slaves from Africa to America.

Jennings's painting combines local pride with strong dissent against the practice of slavery. But the painting understands civilization as a one-way street: Europeans possess culture; Africans lack it. Their gestures of supplication in the foreground of the painting suggest their hunger for cultural and racial uplift. Even abolitionists sympathetic to the plight of slaves viewed Africa as a "heathen" land, and, blind to African customs, they viewed Africans and African Americans as in need of Western values.

Two Versions of Education

THE TWO VOLUMES in Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences, "Agriculture" and "Philosophy," anticipate debates about race that will take place in the following two centuries. Each side in the debate will stress the importance of education, though each side will mean something different by that term. Booker T. Washington, in Up From Slavery (1901), will emphasize the importance of agricultural labor and manual training for black advancement. W. E. B. Dubois, on the other hand, will insist that talented black men and women receive the same advanced intellectual schooling as their white peers (Souls of Black Folk, 1903). This argument over the best means to black empowerment goes back to the tension between "Agriculture" and "Philosophy" in Jennings's painting. The debate will continue well into the twentieth century.

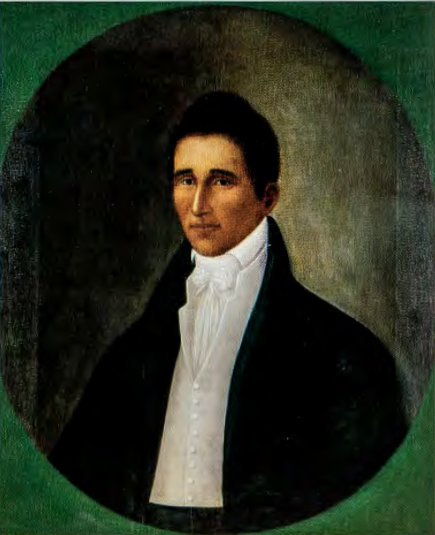

JOSHUA JOHNSTON. Joshua Johnston (also spelled Johnson; c. 1765- 1830), a free black artist active in the Baltimore area in the early nineteenth century, is the earliest known African American painter to succeed professionally as a full-time artist. Documents suggest that Johnston was born into slavery in Baltimore but gained his freedom in 1782. Baltimore had a large and prosperous population of free blacks. Little is known about Johnston's career until he began advertising in the Baltimore Intelligencer in 1798 as a "self-taught genius" who "experienced many insuperable obstacles in the pursuit of his studies."

Johnston painted the merchants, seafarers, military men and clergy who constituted Baltimore's thriving middle class. His portrait The Westwood Children (c. 1807), shows a flair for design and decorative detail (fig. 5.11). The rhythmic pattern of the boys' boots echoes the flow of their intertwined hands and ruffled collars.Johnston experiments with flatness and recession, playing the shallow space of the Westwood children on the left against the deep space of the window scene on the right. The painting teeters between abstraction and realism, balancing the oval faces and cylindrical bodies of the Westwood children against the details of birds, flowers, and buttons.

Johnston's appealing provincial style suited his mercantile patrons. His portraits confirmed their prosperous middle-class status, bestowing upon them a sense of dignity. To hang paintings like Johnston's in the parlor was to announce to all visitors a family's worldly success.

Two surviving portraits by Johnston portray black figures. One of them, Portrait of a Gentleman (1805-10), has been identified tentatively as a portrait of the Reverend Daniel Coker, a member of Baltimore's black elite and one of the founders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (fig. 5.12). Coker published a pamphlet calling attention to the discrepancy between American principles of freedom and the continuance of slavery and urging universal emancipation and Christian egalitarianism.

It is possible that Johnston, like his patron, belonged to a group of black leaders engaged in an effort to create what the scholar Ira Berlin has termed a "united black caste." Rather than separate themselves from slaves or ingratiate themselves into white society, this African American intelligentsia fought to better the economic, social, and political conditions of all blacks. The African Methodist Episcopal Church, for example, brought together free and enslaved blacks in a loosely knit confederation of schools, benevolent societies, and fraternal organizations.

Johnston's portraits of black leaders, though rare, hint at the extensive circle of patronage that brought black artists and clients together. The artist appears to have shared with his African American patrons a taste for middle-class values, a pleasure in the material comforts of American domestic life, and a commitment to black economic and social advancement. Several of his white patrons with abolitionist sentiments probably shared his commitments.