4.4: The Mission System in Texas, Arizona, and California

- Page ID

- 231699

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Across the Spanish Southwest, mission life and architecture varied from region to region. At the heart of the mission institution was the process of reducción, by which the Native population was brought under Spanish religious and secular control. Throughout the Southwest, reducción was accomplished by working with already settled communities of Natives. In New Mexico, as we saw in Chapter 2, Spanish missionaries built their churches on the sites of existing Pueblo villages throughout the Rio Grande Valley. Some twelve-dozen Pueblo villages were reduced to fewer than four dozen by the end of the seventeenth century.

The case was very different in Texas, Arizona, and California, where Franciscan missionaries encountered smaller, more dispersed Native populations. In contrast to the modest scale of the church-convent in New Mexico, integrated within local communities, these later missions were larger and multifunctional. The church was only one building among many, in what was effectively a vast plantation that produced virtually everything needed by the mission. The Indians of Texas, Arizona, and California unlike their counterparts in New Mexico-lacked an indigenous tradition of large-scale building. A small number of itinerant skilled artisans from Spain and Mexico taught Native laborers European building techniques and decoration, taking them beyond the limits of frontier technology. This diminished the influence of Native traditions, and resulted in a more European look among these later missions.

Texas Missions

Throughout the eighteenth century, the Spanish struggled to establish a foothold in Texas, suffering repeated setbacks. Spanish colonists were unable to subdue the Apaches and Comanches who raided the frontier. The threat of Indian attack intensified after Plains Indians acquired horses originally brought from Spain. "Mission Indians," decimated by disease and unused to the heavy agricultural labor imposed on them, deserted or died in droves. Although three dozen missions were established in Texas between the 1680s and 1794, colonization took root only in what is now San Antonio, where five missions have survived into the present. Built of porous local limestone known as tufa, these missions withstood a century of neglect and disuse until the 1930s, when they were restored by the federal government.

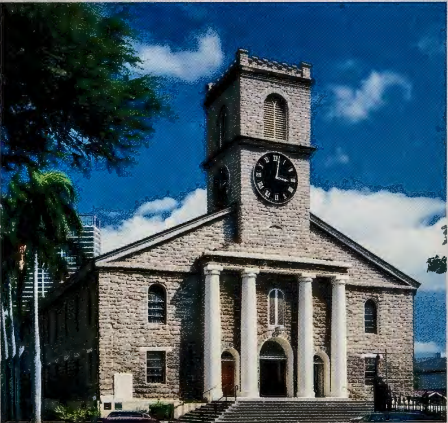

New England Meets Hawai'i

At its westernmost destination, a variant of the colonial church was built in Hawai'i: Kawaiahao Church in Honolulu, completed in 1842 (fig. 4.18}. Designed by the Rev. Hiram Bingham-who had arrived from New England with his wife in 1820 to Christianize the Hawai'ians (inspired by a Hawai'ian who had found his way to Connecticut)-the church was built of coral quarried into blocks of building stone and served as the church of the Hawai'ian royal family. Just as the materials suggest a local re-invention of imported forms, the language of the services is not English but Hawai'ian. The missionaries also introduced milled lumber and the tradition of New England quilting to the Hawai'ian Islands, resulting in hybrid-and novel-achievements in both building and in needlework. The migration of English and colonial architectural forms to locations as distant as Hawai'i suggests the ways that art and religion have historically accompanied-and sometimes paved the way for-colonial expansion.

SAN JOSÉ Y SAN MIGUEL DE AGUAYO. The missions of Texas-even more than those in New Mexico-resembled medieval monasteries, housing all the functions required to sustain the religious community and its converted Indians. In San Antonio, San Jose y Miguel de Aguayo (1768- 82), the best-preserved mission complex in Texas, was called in rm "Queen of the Missions" of New Spain. The mission church is the capstone of an extensive working compound arranged as a vast quadrangle around a central courtyard eight acres in area (fig. 4.19). The courtyard was surrounded by defensive stone walls three feet thick in some places. Towers armed with cannons and swivel guns stood at the corners. The complex protected a garrison of soldiers, cells for Native families, storehouses and workshops for weaving and tanning, and an arsenal, smithy, and kitchen. Arcaded cloisters and a living area for the friars stood at one side of the church.

Mission San Jose is defined by a Spanish Baroque style of architecture and decoration found from South America to Texas. Here, the itinerant Spanish artisan Pedro Huizar created an extraordinary facade portal carved of limestone with a rose window to the side. The facade and all exterior walls were colorfully painted in earth tones and blue, in designs recalling the geometric patterns of Moorish tiles, though today only dim traces are visible. The two-tiered portal and window break the flat planes of the facade (fig. 4.20). Columns with scalloped niches (later filled with statues) stand on either side of the central doorway. Decoration throughout consists of floral and shell motifs, reverse curves, and volutes. This animated surface is set within a sober classical frame of pilasters and entablatures, playing the sculptural, three-dimensional qualities of the architecture against its planar surfaces. Similar applied decoration appears frequently in Mexican colonial buildings, and Huizar may have brought these metropolitan styles from Mexico City to San Antonio.

Texas mission churches, unlike those in New Mexico, were generally cruciform in shape, with transepts and domes. The domes at Mission Sanjose and elsewhere were constructed from a concrete mixture of pulverized stone and sand, poured into wood forms. Workers shaped earth into mountain-like 'berms" or platforms, which could then be used instead of scaffolding to support construction of the dome.

Arizona Missions

During the late seventeenth century, the Jesuits established a chain of missions extending from Sonora, Mexico, into Arizona. These missions were the life's work of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino (1645-1711).

SAN XAVIER DEL BAC. Called the "white dove of the desert," the church of San Xavier del Bae rises like a mirage out of the heat-shimmering desert near Tucson, Arizona (p. 94). Originating as a pilgrimage church under Father Eusebio, the present structure is the third built on the site. The Franciscans, who assumed control of San Xavier after the Jesuits, incorporated the fired brick of the older building into an ambitious new structure, begun in 1783 and completed in 1797. (In 1767, the Spanish king, leery of the Jesuits' growing alliances with the pope, had ordered them to leave their missions in the Americas.).

The name combines a Spanish saint (San Xavier) with an Indian word (Bac) meaning a watering place, anticipating the fusion of Native and European elements in the structure itself. The architectural balance, however, tilts in the direction of European influences. San Xavier was built nearly a century and a half after San Esteban in Acoma, New Mexico (see fig. 2.31), and the differences are striking. San Xavier is constructed of fired brick with a foundation of river stone, and is covered with lime plaster. Its forms are sharper and less malleable than the massive earthen profile of San Esteban, which was constructed by Indian builders who modified and reshaped Spanish forms.

San Xavier probably employed artisans from Mexico directing Native labor. Twenty-nine Spanish families lived at San Xavier in 1795; ten years later all were gone-an indication that they had come for the express purpose of building the church. The presence of Spanish builders at San Xavier helps explain the mission's most characteristic quality-its mixture of forms imported from Mexico City with indigenous versions of the same forms by local Indian workmen. San Xavier represents the northernmost extension of New World Spanish Baroque forms. It is recognizably linked to the more elaborate-and far wealthier seventeenth- and eighteenth-century churches of urban New Spain.

San Xavier, like San Esteban, today serves a largely Indian parish, having preserved a continuous link with the original Indian converts, ancestors of the modern Pima and Papago Indians. The church is a mixture of Baroque, Moorish, Byzantine, and Renaissance elements-the influences central to the architecture of Spain itself. The facade presents two pierced, octagonal towers rising from square bases. For reasons that are unclear, only one of these towers is domed. Throughout the exterior, unembellished wall surfaces- plastered in lime made at a local kiln-highlight the geometries of cube, octagon, and sphere, suggesting architectural links with both Arab North Africa and the Spanish Renaissance. At the center of the facade is a reddish ochre, two-story gabled panel of brick and stucco-materials widely used by the Moors in Spain. The gable breaks into interweaving designs of leaves, grapes, and tendrils, which in their flat relief carving and symmetry resemble the Moorish influenced design that first appeared in Mexican churches in the sixteenth century. Along with the Franciscan coat of arms, medallions, and scallop shells associated with St. James, patron saint of pilgrims (a motif repeated throughout the interior), there are niches in the walls holding statues of the saints. The combination of Moorish-influenced arabesque designs with human figures is unique to the religious architecture of Spain and its New World colonies.

This jewel-like facade anticipates the grand retablo, or altar screen, inside at the end of the nave (fig. 4.21). Both facade and retablo are examples of late-phase Mexican Baroque, which prevailed between about 1730 and 1780. Late-phase Baroque architecture is distinguished by an unusual type of column. Departing from classical usage, the column is visually broken up and reassembled as a series of elongated cubes and inverted pyramids, forms deriving from northern European mannerism as transmitted th.rough Flemish design treatises. Flanders was governed by the king of Spain; its cultural products circulated among Spanish builders.

The interior of San Xavier is more elaborate than the single-naved mission churches of New Mexico, combining the massive weight of Romanesque architecture with Renaissance detailing. It features the bleached white surfaces typical of Moorish buildings with wall painting done by Spanish and Native workers (only traces of this remain today). Entablature and piers, painted to resemble marble, travel the length of the nave in stately Renaissance rhythms. In the eighteenth century, domes became a feature of mission churches; and here a shallow, spherical dome caps the crossing, where transepts and nave intersect, its windows bringing light into this area. In addition, five shallow oval domes, located along the nave, transepts, and apse, simulate a series of cloth canopies floating above the viewer; they are painted to simulate pleated folds.

Like the facade, the retablo (see fig. 4.21) is constructed from fired brick covered with plaster, then gilded and painted. Canopied niches hold statues and scallop shells. Carved and painted images of the saints appear throughout the church. They represent the most impressive on-site collection of religious art in the Southwest-fifty-five sculptures, as well as many paintings. Most were imported, like the skilled labor pool itself, from Europe or New Spain.

The California Mission Chain

Twenty-one missions dot the coastline and immediate inland area of California in a chain from San Diego to north of San Francisco. They represent the final phase of Spanish colonial expansion into what is now the United States, and were large, multifunctional, self-sustaining complexes similar to those in Texas. Ordered by Spain, this late phase of mission construction began in 1769 to counter the threat of Russia's expansion down the coast of California from its foothold in Alaska. The effort was led by the Franciscan Father Junipero Serra (1713-84), whose name appears on streets and schools in modern California and whose idea it was to place the missions at intervals positioned "so that every third day one might sleep in a village," as he wrote to his superior in 1774.

Unlike the village-dwelling Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, coastal California's more nomadic and geographically dispersed Natives, who had lived in relatively small and flexible village groups, harvesting the bounty of the sea and the land, were herded onto missions and forced into strenuous labor. As one scholar has characterized it, the Franciscan friars endeavored to "transform the coastal hunter-gatherer peoples into a peasant class of neophyte Catholics."3

After baptism and all the promises that conversion entailed, their lives became brutally harsh. They were forced, first, to build the missions, and then to live within their compounds, where every aspect of life was regulated by bells dictating times for prayer, for meals, and especially for long days of arduous work. Because the number of Spanish overseers was small, Native labor provided everything-from raising crops to making tallow, soap, and roof tiles. Even visitors of the era remarked on the Natives' harsh lives-the incarceration of these workers in squalid, airless barracks, and the use of whips and stocks for control.

By the age of seven, girls were separated from their parents, to live in locked compounds from which escape was impossible-the only door gave onto the guarded interior walled court. The harsh mission social structure had much in common with southern plantations, only here the masters were Spanish friars and the enslaved workers were Indians.

MISSION SANTA BARBARA. The Mission of Santa Barbara (fig. 4.22) was founded in 1786; however, the present church was completed in 1820, following an earthquake in 1812, which destroyed an earlier building. Located on the coast and dramatically framed by the San Gabriel Mountains, the mission was built principally by the Chumash Indians, and is one of the few California missions that have not been significantly altered. The facade is framed by two stepped bell towers capped by domes and is punctuated by six neoclassical columns. The facade differs strikingly from that of other California missions, a fact explained by its late date. When Junipero Serra died in 1795, Mexican builders, eager to purge the excesses of the Baroque style, incorporated the neoclassical influences that were then appearing in European architecture. Though built by local labor, the Santa Barbara mission employs the same international styles found among the English colonies on the eastern seaboard. Like its eastern counterparts, Mission Santa Barbara derived its form from the language of the classical orders, as widely disseminated in illustrated architecture books.

Just as the economies of the eighteenth- and nineteenth century eastern colonies depended upon the labor of enslaved African Americans, so too did the mission system of California exploit indigenous Californians. Native workers were soon demoralized by the harsh discipline and backbreaking labor enforced by mission life. The combination of disease and malnutrition produced a dramatic decline in the Indian population, undermining the missions' reason for being. There were numerous small rebellions against the California mission system, but they never had any measure of success. The Chumash Indian uprising of 1824 lasted only three weeks, after which some four hundred Indians fled Mission Santa Barbara, never to return. By the early nineteenth century, most missions were abandoned: their nomadic Indian congregants dispersed, and their buildings slipped into steep decline. Following Mexico's independence from Spain in 1821, the California missions were secularized, although Santa Barbara remained under Franciscan control. Decades of abandonment left the missions in ruins. Despite all, Christianized Natives had created a legacy of tilled fields and orchards, extensive stock herds, and other forms of material wealth that prepared the way for later settlers.