4.3: Palladio and "Georgian" Building

- Page ID

- 231698

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

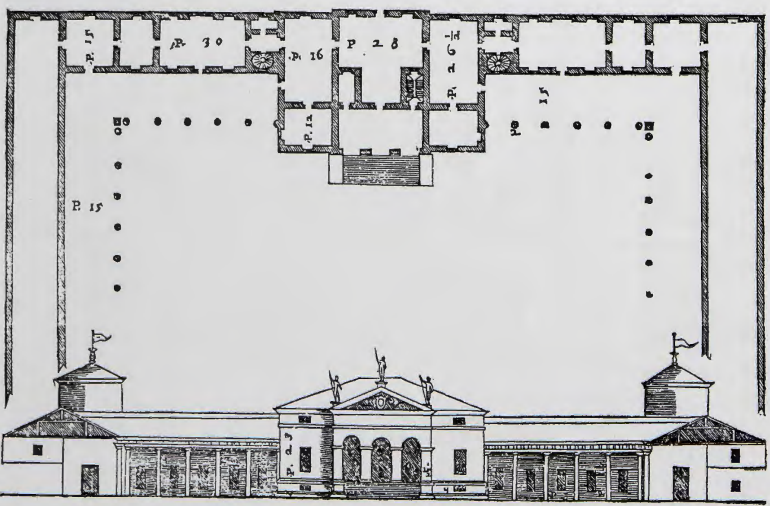

PALLADIO'S FOUR BOOKS. In the second half of the eighteenth century, artists and designers measured and drew newly excavated architectural fragments of Roman antiquity. They extrapolated rules of design and proportion from the classical fragments they studied, inventing along the way accommodations to early modern living (fireplaces, chimneys, glazed windows, etc.). The medium through which this new architectural language traveled was the illustrated book. The most influential book for the English-speaking world was the Four Books of Architecture (I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura) published in 1570 by the northern Italian architect Andrea Palladio. Palladio's book recorded and disseminated his plans and elevations for dozens of villas, churches, and civic structures, making them available for study, extrapolation, and mimicry everywhere (fig. 4.9). But the circulation of the expensive work was necessarily limited to the gentry. Before the development of the illustrated design book the craft of building was passed from master builder to apprentice in a face-to-face transmission of skills. But the arrival of the book as a source of architectural knowledge and communication put the power to design squarely in the hands of gentlemen, and created the figure of the heroic architect with which we are familiar today. Over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries some design books became smaller in size; with titles like The Builder's Benchmate they clearly addressed the artisan as well as the gentleman architect.

Another key aspect of the architectural revolution occurring in the early years of the eighteenth century was the suppression of visible engineering-such as the dramatic roof truss in St. Luke's Church (see figs. 3.24 and 3.25)-in favor of what we can call pseudo-engineering. Instead of revealing the beams and joints that supported a building, Renaissance interiors were plastered over with smooth surfaces, often ornamented with columns, pilasters (attached columns), and entablatures, which only rhetorically reference the post-and-beam structural system used to hold the building up.

Georgian Domestic Architecture

Because this Italian Renaissance style was popular in Britain (whence it spread to the thirteen British colonies) during the reigns of the first three Hanoverian Georges, it is known as "Georgian." Its general principles dominated building practice throughout the region in the eighteenth century. The popularity of Georgian architecture stems in part from the ease with which builders could copy its forms from books. Georgian architecture is characterized by proportional and balanced forms: regularity of design; repeated shapes; proportional sizes; and symmetrically placed elements. The windows of a Georgian building, for example, align exactly with the windows on the floors above or below. In more elaborate buildings, the windows are flanked by pilasters and centered in symmetrically arrayed bays.

MOUNT AIRY, IN VIRGINIA. Mount Airy, in Richmond County, Virginia, exemplifies Georgian architecture at its most expansive (fig. 4.10 ). Compared with seventeenth century practice, its roof is flatter, its facades more symmetrical, with apertures directly over apertures, and doorways centered and emphasized. Changes in planes are marked and highlighted (at corners and where wall planes meet eaves), and the whole structure is raised above ground level. Mount Airy is arranged in three horizontal tiers: a basement story, forming a raised platform for the elevated main story, above which is a subordinate upper story. Following Palladian practice, Mount Airy is flanked by dependencies (small symmetrical lateral buildings, designed to house kitchens, offices, extra family bedrooms, schoolrooms, and such), which are linked to the main rectangular block by subordinate one-story connectors. In sum, it is a composition expressing physical and social hierarchy, as well as "Roman" associations. The unknown architect of Mount Airy would not have seen Palladio's Villa Saraceno (see fig. 4.9), near Vicenza, but he certainly saw an English design derived from it: James Gibbs's drawings "for a gentleman in Dorsetshire" in his Book of Architecture, published in. London in 1728. Because of the rise of the illustrated design book, therefore, an eighteenth-century colonial Virginian could receive instruction from a sixteenth century Italian architect.

Mount Airy was a manor farm and country "seat." The relationship of the main house to the various other structures was one of head to subordinate parts. The manor was a microcosm of the larger society, and all its residents recognized the patriarchal authority that governed it as natural and absolute. These social relations were embedded symbolically in its buildings and landscape. The house stood above its surroundings on a little rise and was visible on axis as a harmonic, proportionate assemblage of parts, signifying for family members, servants, hangers-on, and slaves alike the authority at the center of their lives.

Mount Airy-like other plantations of the period functioned like a small village. The manor house served as the equivalent of a town hall or county seat. Its owners oversaw the social, political, and economic arrangements of the community: producing crops and exporting them to Europe, overseeing the everyday lives of hundreds of people, managing ties with religious and political leaders, and educating its non-African children. All male heads of households (poor, middling, and rich) owned the labor of their wives and children as well as servants and slaves, and owned all the means of production. What tended to distinguish an eighteenth-century plantation from a traditional village was profit: most work of the plantation was designed to enrich a single individual or family, rather than the larger community.

As the scholar Dell Upton has noted, plantations such as Mount Airy employed architecture and the built environment to create two different landscapes: one as experienced by the owner and wealthy whites, and one as experienced by enslaved workers, artisans, tradesmen, professionals, and poor whites. The buildings and surrounding lands of the plantation established, for the world of the white planters, a series of social barriers. Beginning with the estate itself (trees, lawns, and gardens), and continuing with the outbuildings (kitchen, shops, and slave quarters), the plantation was designed as a sequence of spatial boundaries that needed to be crossed, one by one, in approaching the manor house. The plantation house in turn-prominent, as Mount Airy was, for all to see but few to enter- divided its spaces into degrees of ever greater proximity to the master and his family, from the terrace, steps, and doorway, to the large reception hall and waiting chambers, to the dining room and spaces for more intimate conversation. The higher one's social status, the more of these architectural barriers one could pass through. The landscape formed a processional movement from the outskirts of the estate to the manor house and its semi-private rooms, a journey that was mental as well as spatial.

For blacks and poor whites, these same spaces produced a different meaning. Their landscape tended to revolve around familiar, and usually marginalized, locations: the one- or two-room slave huts, the adjacent fields and work areas, and the woods, marshes, and swamps at a distance from the manor house. To some degree, the laborers of the plantation, both enslaved blacks and poor whites, conducted their lives in work and residential spaces that-despite the master's agent's surveillance-they might claim as their own. Moreover, black occupants of the plantation stood partially outside the deferential barriers erected for white visitors. Through their duties as domestic servants, they had real, if covert, access to the main house that allowed them to enter into its intimate spaces as if invisible. Their landscape was less hierarchical than it was defensive, and, on occasion, subversive. This landscape within a landscape converted the distance from the main house into an alternative realm of residences and woods where African American practices could survive.

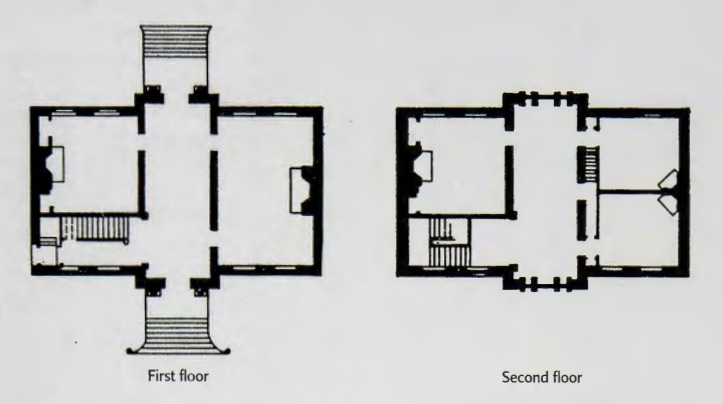

MOUNT PLEASANT, IN PENNSYLVANIA. In the Middle Colonies, Georgian domestic architecture was, in part, similar. In its grandest versions, such as Mount Pleasant (1761), a two-and-a-half-story hipped-roof rectangular structure dominates its flanking dependencies (figs. 4.11 and 4.12). Mount Pleasant is defined by a symmetrical five-bay facade and an emphasized doorway. The land on which this house is built, a knoll overlooking the Schuylkill River, just outside Philadelphia, was bought in 1761 by John MacPhearson, a Scot with two marriageable daughters (as well as two sons). In September 1775 John Adams, later the second president of the United States, visited the house and recorded in his diary: "Rode out of town, and dined with Mr. McPherson. He has the most elegant seat [establishment] in Pennsylvania, a clever Scotch wife, and two pretty daughters.

His seat is on the banks of the Schuylkill. He has been nine times in battle; an old sea commander; made a fortune by privateering; an arm twice shot off, shot through the leg, etc. He renews his proposals of taking or burning ships."2 MacPhearson was robust, assertive, nouveau riche, a retired privateer-that is, a legalized pirate licensed to prey on enemy shipping-and the elegance of his house was probably intended to promote the marriage of his daughters into older, more established families. Being rich in the eighteenth century was important, but belonging to a web of mutually recognizing families was even more important. Key to the family's prominence was its "seat," or family estate, and its alliances within the social structure.

Like most high-style Georgian houses, Mount Pleasant has two nearly identical principal facades, what we today call front and back, both dominated at the center by distinctive features. At the roofline a pediment crowns a ''.jut," advancing the central bay slightly but emphatically the change in planes marked by quoins (large, contrasting corner blocks) at the edges. Lighting the upper hallway, a "Palladian" window lends the dignity of a mini-triumphal arch to the composition. In general, the sash windows composed of twenty-four "lights," or panes of transparent glass-were expensive indicators of wealth in this period. The door surrounds, with their flanking Doric columns "supporting" correct (that is, patternbook) entablatures and mini-pediments, invoke the classical orders at this privileged position.

The building vocabulary used at Mount Airy and Mount Pleasant is so familiar to us that it is hard to see it as novel. It has been much imitated and adapted in the many phases of the colonial revival because its orderly symmetry, its hierarchical masses, and its rhyming forms express a set of ideals that our culture continues to esteem. It has come to represent-in nineteenth-century and later suburbs, up to the present-an idealized Golden Age of civic virtue and social clarity. It should also remind us of MacPhearson and those other eighteenth-century gentry who literally shot their way to the top.

WHITEHALL, IN RHODE ISLAND. Mount Pleasant and Mount Airy are exceptional. Most Georgian building in the colonies was less lavish in scale, materials, design, and in the adoption of the Georgian vocabulary, with less expensive materials and, of course, smaller houses to suit the pockets of the less affluent. Whitehall, for instance (fig. 4.13), built near Newport, Rhode Island, in 1729 to house the philosopher George Berkeley, probably by a builder without access to design books but with an inkling of Georgian design, has the five-bay facade, hipped roof, sash windows aligned precisely above one another, and an entry marked by Ionic pilasters capped by a tidy proportionate pediment-that give it a family resemblance to Mount Pleasant and Mount Airy. But Whitehall is built of wood and is clapboarded. It is not raised on a basement story, and its facade-with its off-center chimney and larger left half-is casually asymmetrical. Most dramatically, its rear elevation abandons all effort at Georgian systems of design and presents a long "catslide" lean-to roof. All of these irregularities are familiar from seventeenth-century construction practice, which persisted side-by-side with the new Italianate forms and combined with them to produce new ( and regionally varying) vernaculars. Although Berkeley- a churchman of the urban elite who had traveled to Italy-undoubtedly thought of the front as the "right" facade, regarding the rear as odd, it was the rear vernacular elevation that, one hundred fifty years later, New York City architects and painters drew and copied, inserting this design "embarrassment" into the Shingle Style homes they designed for their elite clients (see Shingle Style, Chapter 9, fig. 9.17). The tendency of old types to persist in hybridized form, and the tendency on the part of artists, architects, and their patrons to mine the past for visual quotations, remind us that terms such as "vernacular" and "colonial" are chameleon. It is important to understand the past as a fluid place-one where meanings are constantly being remade. The present, in turn, never speaks with one voice; it always drags some portion of the past with it.

Georgian Religious Architecture

The size, materials, location, and architectural vocabulary of a house could tell a passerby a good deal about the prosperity of its inhabitants, but it would tell her little about one of the most important ingredients of identity for the British colonists: their religion. Unlike the French colonies to the north and New Spain in the West (which were almost entirely Roman Catholic), the eastern seaboard settlements were, by 1750, religiously diverse. The arrival of royal governors in the 1680s also brought the Church of England, to the discomfort of Puritans in Massachusetts and also Quakers in Pennsylvania. Scots-Irish immigration had brought Presbyterianism, and Germans had brought Lutheranism. Rhode Island by 1750 was a refuge for religious dissenters; there were Quakers, Congregationalists, Baptists, Anabaptists,Jews, and Anglicans in the capital city, Newport, each congregation with a distinctive building type representing in material form the practices, core beliefs, and history of its group.

THE QUAKER MEETING HOUSE. In 1699 the Quakers in Newport built a large, unadorned meeting house (the central portion in fig. 4.14). They subsequently added onto it on both sides in an ad hoc fashion; but despite their considerable wealth and central position in the local politics, their Meeting House remained unornamented. This architectural straightforwardness served to express the Quaker belief in the inner light of individual souls.

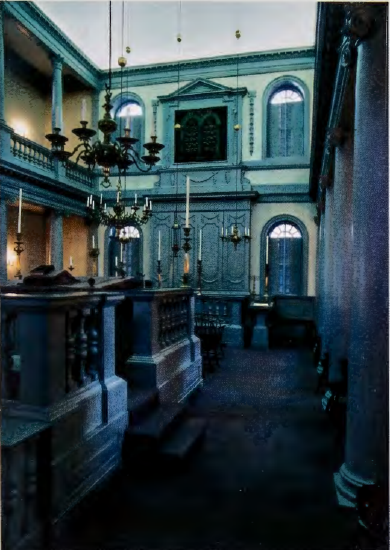

THE TOURO SYNAGOGUE. Newport's Touro Synagogue, by contrast, combines elaborate Georgian architectural forms with traditional Jewish elements (fig. 4.15). Designed by the architect Peter Harrison (1716- 65) in 1759, the synagogue derives from the large collection of English architectural design books that Harrison owned. The building, set at a slight angle to the street, allows the congregants to face east toward Jerusalem when praying. A screen of twelve Ionic columns represents the twelve tribes of ancient Israel. Each column was made from a single tree; together they mark off the perimeter around the elevated Bimah (a raised altar and lectern) and support the Women's Gallery above. This use of classical columns that actually bear weight is rare in the colonial context. It is found most commonly in large-scale public buildings such as synagogues, churches, and statehouses.

TRINITY CHURCH. Nearby Trinity Church (1725) supports a similar gallery above family box pews (fig. 4.16). Trinity is Anglican and is arranged, like St. Luke's a century earlier (see figs. 3.24 and 3.25), as a long rectangle. Where the focus in the square synagogue is on the Ark and the lectern, in Trinity the nave leads to a lectern, a raised pulpit (the sounding board above amplifying the minister's sermon), the altar, and a large east window. In both cases-synagogue and church-the orders add dignity to the space and to the religious services within that space. They permit each building to span great widths, and they establish proportion among all the parts.

THE "COLONIAL CHURCH." Given the wide variety of religious structures that were built in the English colonies, it is perhaps surprising that one single type has come to dominate our idea of the "colonial church." Derived originally from the designs of Sir Christopher Wren, whose parish churches combined the new Italian Renaissance vocabulary with the old Gothic idea of a steeple, and were built all over London after the fire of 1666, this building type was popularized and disseminated by James Gibbs in the eighteenth century. His Book of Architecture provided models, including St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, London, that inspired variants throughout the colonies. In its full-blown form, with a giant portico in front and pilasters marking the bays down the sides, an elaborated steeple, two rows of round-headed windows, and masonry construction, it can be seen in St. Michael's Church, Charleston, South Carolina, of 1752-61 (fig. 4.17). More modest variants were built of wood, omitted the portico, or even truncated the steeple, but this rectangular white structure with roundheaded windows and aspiring steeple became the archetypal church for Protestants of all denominations as they carried their religion and their ideas about architecture throughout the continent.