4.5: The Crafted Object

- Page ID

- 231700

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The arts of the Southwest developed, as we have seen, from the complex interactions of Spanish, Moorish, and indigenous traditions. A parallel situation existed among the colonies of the eastern seaboard, where British and Italian styles were joined by a third, more distant influence: Asia . Surviving objects from the eighteenth century reveal a strong Chinese influence, for China's superior abilities in the manufacture of ceramics and silk attracted traders from around the world. Equally important, colonial drinking habits supplemented fermented alcoholic drinks made from locally grown crops (ale, beer, cider) with imported boiled water drinks, tea, chocolate, and coffee, made from plants grown in the tropics and Asia. New tastes created new global markets and substantial trading ports for Western trade in China and India . The adventuring Westerners in these exchanges looked at Asian culture and Asian art from a decidedly "outsider" perspective: they saw Asian aesthetic forms not on their own terms but as exotic and different from European ones. By the same token, their Asian trading partners, anxious to guard trade secrets and protect their societies from foreign influence, restricted Western access to specified ports only.

Colonial Money

COSTS , DEBTS , WAGES, AND VALUES in British colonial records were expressed in pounds (abbreviated £), shillings (s), and pence (d), and written, for instance, as 1/3/0 for one pound three shillings. Twelve pence equaled one shilling and twenty shillings equaled one pound. Deborah Franklin's outlay of 23 shillings, then, was 1/3/ o. Transactions between gentlemen were usually calculated in guineas (a guinea being the equivalent of one pound plus one shilling, a sort of super pound). Although this was the monetary system in which transactions were computed, British currency was scarce in the colonies. Silver (and sometimes gold) coinage from other countries such as Holland, France, and Portugal circulated as cash. Equivalency tables were printed for the benefit of traders, but more often small pocket scales facilitated the use of such foreign coins by weight rather than face value. The most widely circulated coin in the British colonies was the Spanish dollar, as the world's source of precious metals in the eighteenth century was New Spain. More than 20 million Spanish dollars were minted annually in Mexico City in the eighteenth century, most of them shipped to Madrid. Some treasure ships were intercepted by colonial privateers as they crossed the Caribbean, their cargoes enriching colonial purses rather than the Spanish Crown. In Spanish currency a dollar equaled eight reales. Spanish dollars were known, therefore, as "pieces of eight." Because they were not official currency issued by the British sovereign, they could be melted down to make objects such as Franklin's silver spoon or clipped and cut to create subcategories of currency. Dollars were routinely cut into four equal pie-shaped sections called "quarters," and these halved to make eight "bits." This unofficial currency was so important that in 1792 the dollar (rather than the pound) became the basis of official U.S. currency. Silver objects created in the colonies contain the same proportions of trace metals as Spanish dollars, confirming the flow of precious metals northward and their fabrication into art.

Ben Franklin's Porringer

In his autobiography (written in the 1770s), Benjamin Franklin recounts his rise from penniless runaway printer's apprentice to successful author, scientist, and diplomat. He includes this vignette of his domestic life in the 1740s:

My Breakfast was a long time Bread and Milk, (no Tea) and I ate it out of a twopenny earthen Porringer with a Pewter Spoon. But mark how Luxury will enter Families, and make a Progress, in Spite of Principle. Being call'd one Morning to Breakfast, I found it in a China bowl with a Spoon of Silver. They had been bought for me without my Knowledge by my Wife, and had cost her the enormous Sum of three and twenty Shillings, for which she had no other Excuse or Apology to make, but that she thought her Husband deserv'd a Silver Spoon and China Bowl as well as any of his Neighbours. This was the first Appearance of Plate [silver] and China [porcelain] in our House, which afterwards in a Course of Years as our Wealth encreas' d augmented gradually to several Hundred Pounds in Value. 4

The account is both factual-about an upgrade in his material possessions-and a parable about aesthetic acquisition and a global economy. It coyly casts his wife, like a "daughter of Eve," as the agent of Franklin's "fall" into consumerism and material competition with his "Neighbours." Yet he concludes with a self-congratulatory assessment of his current position in the world as measured by the possession of china and silverware worth "several Hundred Pounds." By this last comment Franklin tells us two things: his taste has improved, and he has become a gentleman. For eighteenth-century self-starters like Franklin, silver and porcelain provided a measure of social identity among successful peers.

Silver and porcelain imported from China were not just luxury goods but, as Franklin implied, a sort of savings account. They retained their value and could be sold or traded readily. (Indeed, silver items were often marked on the bottom with their weight to facilitate such transactions.) Even a near-indigent man might die in possession of a silver spoon or a few silver buttons. This was a way spare cash could serve a useful function, remain "liquid," and even suggest-as in Franklin's case- the possibility of upward mobility.

Franklin's original implement, the pewter spoon, was made of tin and antimony- probably from Britain. Pewter was the common material for spoons, plates, bowls, and other tableware in the eighteenth century because it was plentiful, easy to cast at low temperatures, and easy to recycle when damaged. Silver was not just more valuable as a material; it also required a higher level of artisanal skill and labor. The move from an earthenware bowl to a china bowl was a shift of a different sort: from an object made by a lone local potter, using local clays fired at low heat, to an object made by a factory of workers halfway around the globe, using special clays and very high temperatures. The Chinese product was light, white, translucent, and strong (see fig. 5.25), whereas the discarded earthenware bowl was heavy, reddish brown, opaque, and easily damaged. With her purchases, Deborah Franklin had changed the look of her husband's modest breakfast table as well as the family's "portfolio." To eighteenth-century eyes, few materials matched the reflective qualities of silver or the magical thin whiteness of Chinese porcelain.

Paul Revere the Silversmith

Silver was used in ceremonial, religious, and public places, as well as in the home. Churches in particular served as major patrons of colonial silversmiths. Characteristic of such patronage is a set of six tankards made by Paul Revere (1735- 1818) in 1772 for the Third (Congregational) Church of Brookfield, Massachusetts, with funds provided in a parishioner's will (fig. 4.23). Such gifts had been common practice since the earliest years of settlement. Consistent with their avoidance of special clerical vestments, Puritans, Congregationalists, and many other Protestants took communion from beakers, two-handled cups, and mugs as well as tankards. These were the same vessels used in the home, and, just as in the home, they were passed around among those assembled. Over the course of the eighteenth century, the sharing of vessels decreased at most socioeconomic levels, except in ceremonial contexts. As the sense of privacy increased, the tradition of communal sharing decreased.

Paul Revere was a talented silversmith as well as a celebrated patriot (see fig. 4.32). We know his business well what he made for whom, and when-because some of his account books and many objects with his touchmark (stamp) have survived. Beyond fashioning a wide range of silver objects- tankards and teapots, spoons, and frames for miniature portraits- he was an engraver, produced prints and illustrations, made gold jewelry, practiced dentistry, cast bronze bells and cannon, and assisted in the Revolutionary cause with his knowledge of metallurgy.

SONS OF LIBERTY BOWL. Revere's most famous commission is known as the Sons of Liberty Bowl of 1768 (fig. 4.24). Silver vessels are not cast but "raised," that is, a flat disk of silver (in this case one weighing three pounds) is hammered over a small anvil to gradually "raise" the desired shape. Once completed, the object is frequently engraved. The Sons of Liberty Bowl bears an inscription commemorating the solidarity of the ninety-two members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives who voted in 1768 "not to Rescind" their letter of defiance decrying the Townshend Acts (onerous taxes, especially taxes on tea)- that is, not to buckle under pressure from the British Crown. This cohort of elite men commissioned this substantial bowl to commemorate their daring, "undaunted by the insolent Menaces of Villains in Power" (as the inscription puts it), and drank toasts from it when they gathered. By publicly criticizing their government, they risked everything; that they did so as one body helped to ensure the success of their revolutionary undertaking. Silver objects for public use often express collective memories-a congregation's memory of the deceased (in the case of church silver) and in this case the merchants' memory of their courageous stand in the face of what they understood to be an attack on Magna Carta and English liberties. In the private sphere, too, silver often was designed to evoke memory. It passed from generation to generation, often with new names engraved beside those of their predecessors, a physical link to the family's ancestral past.

The Line of Beauty

Revere's bowl is frequently reproduced-replicas are given as trophies and wedding presents every day-not because there is a clear public understanding of its history but because its shape is considered beautiful, a "classic." Its contour is generous, curving upward until, nearing the lip, the curve flares outward, creating a gentle S profile. This S-shaped contour, also seen in the handles of Revere's tankards, is one of the key elements in eighteenth-century design. We saw it in the serpentine paths of Washington's approach to Mount Vernon (see figs. 4.6, 4.7), and we will see it below in portraits. Where did it come from and what meanings became attached to it?

The English artist William Hogarth (1697-1764) called the S-curve the "Line of Beauty." In 1753 he published a treatise entitled The Analysis of Beauty, in which he discussed (and diagrammed in a series of engraved plates) the presence of this line in sculptures from antiquity, ladies' corsets, chair legs, and human anatomy. Contrasting ideal curves with others that appear too stiff or too loose, he makes a case for a universal principle of design. This is not, he believes, human invention, but rather a principle irLherent in nature, like the harmonic relationships of the octave in music. Conversely, angularity and abrupt contrasts without variety display, for Hogarth, an absence of beauty. While Hogarth's book did not introduce the serpentine line-indeed, it had been used in English gardens and decorative arts for some decades-it did codify and popularize its appeal.

THE COMBINATION OF AESTHETIC LANGUAGES IN DECORATIVE OBJECTS. Looking again at Revere's tankards, we see them merging two aesthetic systems-the Hogarthian serpentine line and the architectural language of the orders. The S-curve is associated with nature (flowers, faces, bodies) and with surprise and happy accident. The orders, on the other hand, are linked to antiquity (both architectural and human history) and with rationality and universal proportion. Structured like a miniature building, with moldings derived from column bases, the tankard's body is divided into proportionate parts and marked by a band reminiscent of the stringcourses that define stories on buildings. The tankard is surmounted by a lid (also derived from classical moldings) and a finial (as is, for instance, Palladio's Villa Saraceno; see fig. 4.9). These two aesthetic languages, the classical orders and the S-curve, are combined most frequently in decorative art objects. Look again at the foot of Revere's Liberty Bowl; it replicates, in miniature and upside down, the capital of a Tuscan column. Revere, like other artisans of his day, designed in both of these aesthetic languages.

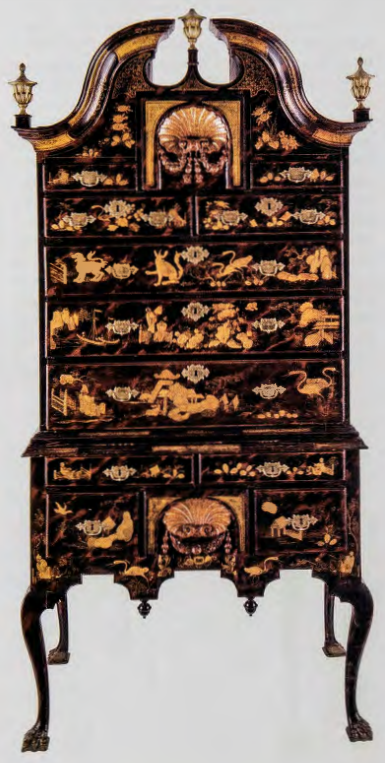

In architecture of the period, the rule of the orders and of geometry is absolute. In furnishings, the serpentine line intrudes; here flora and fauna (shells, cabriole legs with paws or claws) disport themselves. The S-curve cabriole leg provides a very different metaphor than do the classical orders for the weight-bearing function of these supports; it seems to flex, like an animal's leg, rather than standing erect like a post. In the case of this high chest we see the cabinetmaker's reconciliation of these two disparate vocabularies (fig. 4.25). Like Revere's tankard and Mount Pleasant, the high chest is divided into three hierarchical sections-a 'basement" set off from the "main story" by an architectural molding, .µid, on top, a pedimented "attic." This pediment is basically an architectural feature (like the pediment over the door at Mount Pleasant), and is embellished with architectural moldings, but it is carved into a double serpentine to echo the legs.

Although a novelty in the West in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the serpentine leg had been used in China since at least the fifteenth century, and this form may recall Chinese antecedents. Certainly the surface of the Boston-made high chest is based on Chinese sources. Gilt imaginary creatures, flowers, and figures cavort in unperspectival space across the drawer fronts. Called ''japanning," this surface treatment mimics in paint, gilding, and gesso (a plaster material that gives the figures relief) Chinese lacquer chests imported to the West.

Unlike colonial oak chests from the seventeenth century (large, undifferentiated containers like trunks), the high chest displays an important eighteenth-century development: drawers. For a burgeoning consumer culture, in which more individuals had more things (especially textiles), drawers allowed greater organization and easier retrieval.

The Colonial Artisan

Less wealthy householders could not afford japanned high chests, but these people were part of the same culture, and participated in the same economy, through employment as mariners, sawyers, porters, clerks, or artisans. How did artisan businesses work? How did craftsmen learn the theory and practice of design, the management of tools and materials? Many men in the British colonies were artisans- pewterers, silversmiths, cabinetmakers, cobblers, tailors, housewrights, barrelmakers, and others. Neither working-class nor gentry, artisans occupied a broad spectrum of social positions in between. Master craftsmen were owners of property; businessmen who commanded the labor of others; merchants who marketed the goods they produced; masters of tools, materials, and techniques; and lastly, educators of the next generation of craftsmen. Lesser artisans included propertyless journeymen: laborers who worked for wages and, with the accumulation of capital, might aspire to master status. A shop also included apprentices, young men bound by contract to work without wages in exchange for learning a marketable skill.

Artisans learned their trades not in school but on the job. Most began as apprentices at age thirteen or fourteen, when their fathers contracted for them to leave home and live for seven years with a master craftsman. In exchange for learning a trade, apprentices received knowledge in lieu of wages; they promised to be obedient and diligent.

JOHN GODDARD, MASTER CABINETMAKER. A master craftsman ran his home and business as a single economic and social unit.John Goddard (1723-85) oversaw a successful cabinetmaking shop in the rear of his two-and-a-half-story house. With the assistance of apprentices, journeymen wage workers, servants, and perhaps his children (three of his sixteen children are known to have become cabinetmakers), he produced such objects as the tea table in fig. 4.26. The edge has been raised slightly to safeguard the Chinese porcelain the table was intended to support and display.

Goddard's shop-like others nearby-also produced larger, more complex mahogany objects, such as the desk and-bookcase (fig. 4.27), which were made for local sale as well as for export to the West Indies. Like chests of drawers, desks were an eighteenth-century innovation- in this case tied to the increasing importance, in a newly international economy, of record keeping, correspondence, and bookkeeping. A New England design, the blockfront desk, with its pattern of convex-concave surfaces, marks one of the high points of colonial art. The desk combines rhyming forms, an architectural vocabulary (note the quarter columns framing the corners), and the sinuous S-curves of the shells to form an extraordinarily inventive, well-proportioned, and well-crafted object.

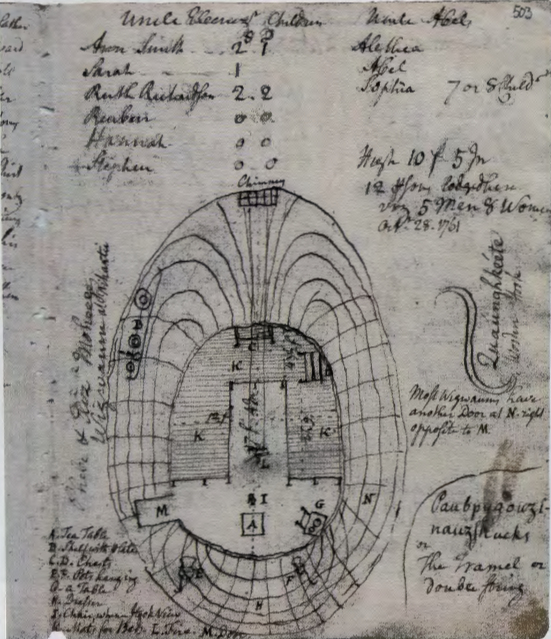

The Cosmopolitan Wigwam

Probate records make it clear that by the end of the eighteenth century even householders of only moderate means had many more possessions than their counterparts a century earlier. Ezra Stiles-minister, Yale College president, and early ethnographer-was interested in the welfare of Native Americans of the Connecticut coast. Stiles noted, for instance, the number of wigwams ( domed houses made of bent saplings covered by bark, used by many Indian peoples in the East) and "English houses" (Native American homes built of milled lumber) in Native settlements on his route. On October 26, 1761, he visited the wigwam of Phebe and Elizabeth Moheegan at Niantic, Connecticut, and measured and sketched the interior (fig. 4.28). Their wigwam was 17 feet 4 inches long and 12 feet wide. It had a raised U-shaped platform with mats, which served as seating and beds (K); a fire was located on the floor between the mats (L). Its furnishings included a chair (I), a table (G), two chests (C and D), and a dresser, that is, a chest of drawers (H), and, most conspicuously, at A-on an axis with the entrance and the fire-a tea table. This tea table and chest of drawers illustrate the role of material objects in the process of culture change. They also provide evidence that Native Americans developed a taste not only for tea, but for the ceremonies and conveniences of ambient English culture. Like Ben Franklin's Chinese bowl fifteen years earlier, the arrival of tea and a tea table in the Moheegan wigwam forms a vignette of international horizons and changing cultures.