4.2: Virginia- Eighteenth-Century Land Art

- Page ID

- 231697

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)By the early eighteenth century, the lands along the seacoast and riverways in British America had been largely settled and put to use. This was a handmade landscape of fields cleared of forest and rocks, marked by fences, pathways, and service buildings. A typical farm was worked by its owner, his family, hired help, and, in some cases, servants. Europeans, Indians, and, increasingly, Africans, provided wage labor, sometimes working off an indenture, sometimes (especially in the southern colonies) toiling as slaves. The property owner made fundamental decisions about the use of land and labor. He was judged by others on how well he used these resources, whether prudently or wastefully, whether resulting in a "fine farm" or a poor one. The closer to the house, the more orderly the land was expected to be: trees in neat rows in orchards, for instance, often abutted the house, whereas woodlots (bits of residual forest regularly culled for firewood) were kept at a distance.

OAK ALLEY PLANTATION (VACHERIE, LOUISIANA). In the early eighteenth century, large landowners favored axial vistas lined by trees planted in straight rows up to a mile long. At Oak Alley Plantation, Louisiana, flanking rows of live oak trees, planted in the 1730s, survive and ennoble the approach to a house built a century later (fig. 4.5). Such symmetry had precedents in Italian villas such as Palladio's Villa Emo. Suggesting control, orderliness, and good government, the axial vista concentrates emphasis at the center. It implies self-assurance-a system with no surprises and no doubts-and asserts the occupant's claim of power and possession. Although persisting in America and France until the end of the eighteenth century, in England this geometric style of landscaping gave way to a new and different attitude in the middle decades of that century. One of the first practitioners in the New World of this new way of seeing and organizing the landscape in "natural," rather than formal, terms was George Washington.

MOUNT VERNON. The idea behind the organization of space at Washington's home, Mount Vernon, in Fairfax County, Virginia, began during the early 1700s in England, where the architect (and painter) William Kent began designing estates that replaced straight lines, symmetry, and geometric planting beds with pastoral landscapes of greenswards, meandering pathways, and indirect approaches. Kent emphasized variety and visual adventure, rather than controlled vistas. Viewers beheld prospects of animals grazing on meadows interrupted and bordered by irregular groves of trees. Kent's circuitous routes to the manor house produced the delight of surprise rather than the satisfaction of predictable axial patterns. The gentry and planter classes viewed themselves as stewards of nature's order, and they took pleasure in the beauty that such order produced. They modeled themselves, and their estates, on the pastoral ideals of the Roman Republic.

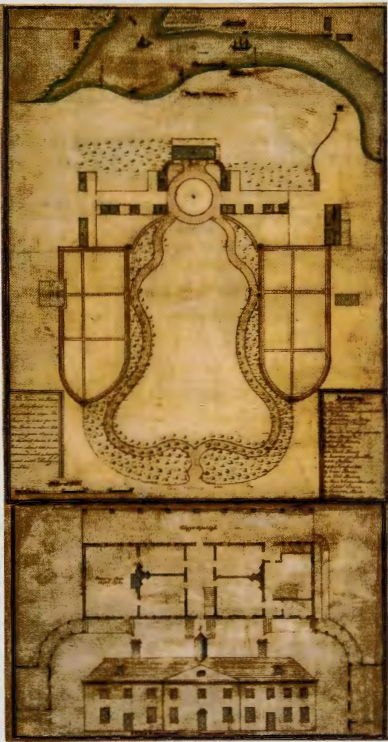

George Washington was a surveyor and farmer as well as a military strategist and president. He knew a great deal about land, crops, topography, and trees. Mount Vernon, his home farm with four contiguous satellite farms, produced wheat, alfalfa, rye grass, hops, hogs, sheep, turkeys, and dairy and beef cattle; but, in accordance with the new aesthetic, only the pastoral landscape of trees, lawn, and grazing animals was visible in the approach to the house or in the vistas from it (fig. 4.6). Washington expressed his interest in the visual experience of those approaching or leaving Mount Vernon in a directive to his manager in 1797: "In leaving the clumps [of trees], if it can be done consistent with the thick growth of the Trees, pay attention to the look of them, in going to or returning from the house." 1 This concern for the pictures formed by irregular topography and for natural planting undelies the approach to Washington's home. Emerging from a little dell and small fo rest, the visitor crossed an open meadow and then once more viewed the house on axis across the lawn before passing through a gate at the ha-ha (a retaining wall and ditch designed to contain animals but invisible from the house; see the bottom of the site plan; fig. 4.6). Deflected once again, the traveler could follow one of two serpentine pathways along bosky woods, which Washington called "wildernesses," to the forecourt and the house.

The approach was one of indirection, deflection, and visual variety. Looking outward from one facade of the house one could see trees, meadows, and-kept at a distance from the house by the ha-ha (fig. 4.7)-grazing cattle, horses, and sheep. This was the picture of pastoralism- a combination of "fenceless" open meadows and irregular clumps of trees- that Washington and his peers admired in English practice. They associated the pastoral landscape with the recovery of agricultural and political virtues linked to classical antiquity and republicanism.

The route to Mount Vernon described above was for the owner and his guests. Others, including enslaved Africans who provided most of the work force on Washington's farms, used a service road. The slave quarters (not shown in fig. 4.6) flanked the square greenhouse in the walled garden on the left in the site plan. The various outbuildings- carpentry shop, spinning house, salt house, smokehouse, wash-house, stables- formed a businesslike "street" at right angles to the forecourt axis. These outbuildings processed the crops and provided the services necessary to keep the plantation running. The landscapes of labor, business, and money were thus axial, while the landscapes of leisure, respite, sociability, sport, and aesthetic pleasure are marked by serpentine lines and greenswards, relieved by the variety and shade of deciduous trees.

Mount Vernon provides an early glimpse of an aesthetic preference still informing our concept of the comfortable life today-one still reflected on house lots throughout suburbia. Separated spatially from sites of labor and production, suburban zones, associated with health, privacy, shade trees, lawns, curving roadways, and serpentine walkways (that is, with beauty and repose), are a central feature of the American dream.

The Classical Orders

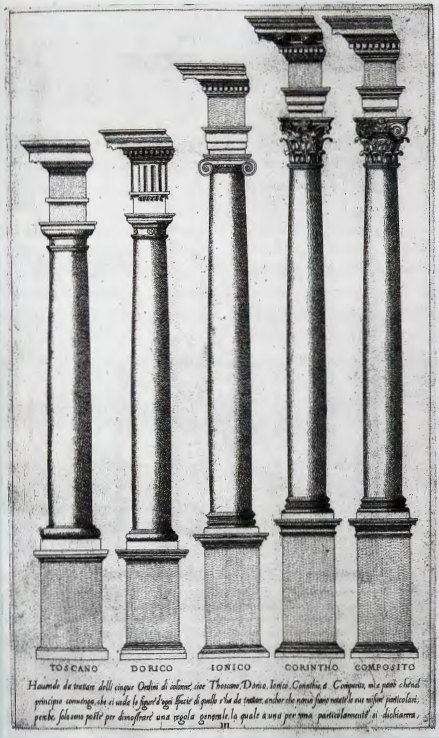

RENAISSANCE DESIGN REVIVED what we term today the "classical orders," an architectural hierarchy codified by the ancient Greeks, which includes unornamented columns (Doric), columns with scrolls at the top (Ionic), and columns with elaborate carvings of acanthus leaves at the crown (Corinthian). Two other column types, Tuscan and Composite, later brought the list of orders to five. Tuscan columns combine a simple capital and base with a plain shaft. The Composite order mixes Ionic with Corinthian. Design books from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century opened with a plate of the five orders, which constituted the basic syntax of architectural form . The classical orders determined a building's proportions, moldings, decorative detail, and expressive character (fig. 4.8).