7.8: Sculpture (1970-2000)

- Page ID

- 130546

Introduction

By the 1960s, the concept of sculptures was changed, the trend towards abstract and figurative firmly in place as traditional ideas were rejected. New materials were available, and sculptors began to experiment with them. The period also brought more sophistication to create and manufacture sculptures, especially oversized images. Sculptors no longer created a single figure out of marble or bronze, and the use of multiple materials involved additional people beyond the artist. Projects, particularly those outdoors, became collaborative efforts with landscape designers and site architects. Site-specific and environmental works on a grand scale were pioneered during this period. The landscape was the basis for the sculpture for some artists, and works were integrated into existing environments.

Materials were important choices for each artist based on technology and the placement in an environment. Those sculptors using metal needed a broad expanse of space and technology to cast or weld the metal. Other sculptors who made large works in factories required trucks and oversized cranes to transport and install their work. Some artists found materials in the environment and used them to create a natural work, while others transformed natural elements with unnatural materials. Some art was permanently installed in this period, while other artwork was temporary and responsive to natural forces.

Richard Serra

Richard Serra (1939-) was born in San Francisco. His father worked in the steel mills as a pipefitter and influenced Serra's eventual use of steel for his sculptures. Serra received bachelor's degrees from the University of California and Yale, adding an M.F.A from Yale and a Fulbright scholarship. While he was in college, he also worked in the steel mills to support himself, learning the process of melting and rolling metal. Serra even developed a list to describe his work, including to hurl – throwing molten lead against a wall and to roll – rolling the metal. By the late 1960s, he started creating large-scale sculptures on a site. Most of Serra's work focused on Minimalism for his oversized steel structures.

Joe (7.8.1) was an early site-specific, permanent sculpture, a commission for the late Joseph Pulitzer Jr. Serra made the immense work from a large plate of hot rolled steel shaped into a spiral. The weathered steel sculpture stands in sharp contrast to the modern square white building. The rolled steel walls widen and narrow as the viewer traverses through the shifting contours of the spiral path surrounded by steel, only the blue sky above visible. Serra described the experience of walking through structure, "It is as if your body becomes its roller coaster, one tracked not up and down but round and round."[1]

Clara Clara (7.8.2) was named after Serra's wife. The sculpture has two weathered steel bands curving away from each other. At one point, they almost touch, although there is a narrow pathway for people to move through. The sculpture brings the feeling of wide doors opening and inviting the viewer in, only to be squeezed in the middle, then moving along the sides open again.

Intersection II (7.8.3) is formed from Serra's favorite material, weathered steel. The massive four panels appear to be precariously balanced. The narrow leaning angles of the walls invite people to walk through the dark, rusted surfaces. Each piece of steel is sloped and curved, forming a central space in the middle of the ellipse. Serra said, "The viewer in part became the subject matter of the work, not the object. His perception of the piece resided in his movement through the piece, [which] became more involved with anticipation, memory, and time, and walking and looking, rather than just looking at a sculpture the way one looks at a painting."[2]

Elizabeth Catlett

Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) was born in Washington D.C. and lived there as a child. Her grandparents were freed slaves and often told Catlett stories about Africa and the hardships of slavery. She graduated from Howard University with outstanding grades; however, Howard was not her first choice. Her original admission into Carnegie Institute of Technology was overturned when the university discovered Catlett was black. Although she was always interested in art, the concept of a black woman as an artist was not acceptable, and Catlett majored in education. She admired the work of Grant Wood and decided to attend the University of Iowa's graduate program where Wood was a teacher. She was accepted into the university but was not allowed to reside in the dormitories and had to rent a room in town. Catlett earned a Master of Fine Arts at the university. She spent time in Mexico studying sculpture and was active in social politics. Because of Catlett's activism, she was barred from returning to the United States; instead, she became a citizen of Mexico.

Throughout her career, Catlett consistently worked making prints while shifting to her main art of sculptures. She used multiple types of material for her sculptures in various sizes and different themes of famous to ordinary people. Her major works were black women whom she depicts as strong and caring with their torsos slanted forward to demonstrate attitude. Pensive Figure (7.8.4) portrays a sculpture of an abstracted woman sitting thoughtfully, gazing into the distance. Viewers might feel they had to walk quietly while looking at the bronze statue, unwilling to interrupt the woman's thoughts. Her clothing style is unknown until the bottom half of the figure, and it appears she wears a dress based on the line above her crossed legs.

El Abrazo (The Embrace) (7.8.5) demonstrates Catlett's exceptional use of wood. The work is carved from a single piece of wood, and she used the grain of the mahogany to accentuate the entwined bodies. The pair's faces look outward at the viewer, not at each other. Their direct gaze lets the viewer share their humanity. Catlett stated, "I still work figuratively, trying to express emotion through abstract form, color, line, and space…Even in more abstract sculpture, I attempt to get a reaction, possibly by a strong upward gesture, or a close tight feeling between two figures."[3]

Magdalena Abakanowicz

Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017) was born in Poland; her mother descended from previous Polish nobility. The family had fled an earlier Russian invasion of the Polish countryside, and they moved to the city. Abakanowicz was only nine when the Nazis invaded Poland. During the war and occupation years, the family lived outside of Warsaw and were part of the resistance. After the war, the Soviet Union controlled Poland, and the Soviets defined art as Socialist Realism, the only acceptable art for artists. Anything modern or style influenced by Western art was outlawed, and art was completely censored. Abakanowicz attended different art schools and was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in 1950-54. The laws of Socialist Realism forced strict rules for the students to follow, and realist portrayals of traditional 19th-century images became the only thing taught at the university. Abakanowicz believed the Academy was rigid and challenging to learn and said, "I liked to draw, seeking the form by placing lines, one next to the other. The professor would come with an eraser in his hand and rub out every unnecessary line on my drawing, leaving a thin, dry contour. I hated him for it."[4] Abakanowicz did take many textile design classes; the methods she learned later influenced her work.

When Abakanowicz first started working as an artist in Poland, the Soviet-controlled country was relatively poor, and artists had little access to materials. She gathered any pieces of materials she found and kept them stored under the bed for possible use. Embryology (7.8.6) was made from rough-hewn fabrics she stuffed. She created a series of different installations using fabric because she liked the concept of no tool between her hands and the material. Her hands were the energy creating the sculpture. The objects in this installation are strewn with no order creating a disturbing scene, appearing as bodies of some sort. Each element seems heavy, like a dead weight from afar. Closer inspection reveals fabric with seams and stuffing, soft to the touch. Because of the brutality of the war and the harshness of Soviet control, many wondered if the stacked figures were a sign of Auschwitz. The human figure was an essential part of Abakanowicz's work, whether overt or implied.

Throughout her sculptures, her work used different materials in a diversity of forms, as she always returned to the concept of the fragility of humans. Space of Human Growth (7.8.7) covers 2,012 square meters. The oversized concrete shapes are undefined, the meaning left to the viewer. Abakanowicz always abstracted her forms, living things, ambiguous and open to the viewer's interpretation. Installed in a park in Lithuania were the objects unopened blossoms, or parts of the human body or maybe even haystacks, open for viewer interpretation.

Bronze Crowd (7.8.8) is a set of bronze abstracted figures standing emotionless. Abakanowicz based her work on references to the turmoil of her past, of war and brutal Soviet occupation. She said, "It happened to me to live in times which were extraordinary by their various forms of collective hate and collective adulation. Marches and parades worshipped leaders, great and good, who soon became mass murderers. I was obsessed by the image of the crowd, manipulated like a brainless organism and acting like a brainless organism. I suspected that under the human skull, instincts and emotions overpower the intellect without us being aware of it."[5] The statues in this installation are devoid of any hint of feeling or thought, just the lineup of humans dutifully standing in a row. Even their clothing is wrapped tightly around their bodies, removing all freedom of movement as the leaders control them. The control of art education by the academy Abakanowicz attended is evident in her artwork as she consistently moves beyond the insistence of realism into the consistency of abstraction.

Ten Seated Figures (7.8.9) appear to be the same, all sitting in a row, legs down, backs straight. A closer look reveals the individuality of each one as the protective patina is applied differently, and the surfaces are wrinkled and textured. The figures are headless; perhaps they do not need brains to think when leaders rigidly control them.

Katsura Funakoshi

Katsura Funakoshi (1951-) is considered one of Japan's leading visual artists, currently living in Tokyo. His father was a sculptor, and Funakoshi learned at first from his father. He attended the Tokyo University of Art and Design for his Bachelor of Arts and the Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music for a Master of Arts degree. Funakoshi became a serious carver in 1980 using camphor wood. Thematically, he combined Asian and Western features in the sculpture and mixed reality with fantasy to develop a certain spirituality. His trademark was to carve the hybrid figures from the waist up, each one different. Funakoshi used the wood grain as a visible carving strategy and left the marks from his carving tools. When he painted or polished the figure, Funakoshi generally left the crown or top of the head unpainted. He made the eyes luminescent, almost life-like, to engage the viewer. The materials he used for each sculpture were essential to him. Funakoshi stated, "I'm interested in human existence, a statement concerning humanity. The material I use-wood for sculpture, paper for the drawings, and charcoal or pencil-is important, it influences the result. I am seeking the perfect tension or moment between the material and the image."[6]

Am I Floating? (7.8.10) is made from camphor wood, her arms and torso painted with light and almost translucent turquoise. Her shoulders are pushed upward, giving more room on her chest for the pendulous breasts. The statue is not decorated or distorted with other images, making her relatively simple.

A Lunar Eclipse in Forest (7.8.11) followed the same format for the image; only the torso is distorted, her neck elongated. Made from camphor wood and painted in tones of sienna, the body is the lightest section. Her hands appear as appendages on the rounded wings, and she stands on four thin legs helping to balance her spherical body. In Am I Floating?, the figure looks straight out at the viewer, while the figure looks downward in this image.

Andy Goldsworthy

Born in England, Andy Goldsworthy (1956-) was a laborer on farms as a teenager. He graduated from the now University of Central Lancashire with a Bachelor of Arts and moved to Scotland, where he still resides. Goldsworthy is a sculptor and photographer who creates Land Art or Earth Art. He works with natural materials in their location, his art moving through creation, completion, and disintegration stages. Goldsworthy states, "I enjoy the freedom of just using my hands and 'found' tools – a sharp stone, the quill of a feather, thorns. I take the opportunities each day offers; if it is snowing, I work with snow, at leaf-fall it will be leaves; a blown-over tree becomes a source of twigs and branches. I stop at a place or pick up material because I feel there is something to be discovered. Here is where I can learn."[7] When Goldsworthy goes out into nature, he observes his surroundings to decide what he will create. Most of his work disappears, naturally decaying except for some of his stone walls. Even a wall does not remain the same; grasses grow in the cracks, insects make a nest or animals remove a stone. Most of his art is visible to the public through the photographs he records. Goldsworthy also takes photographs at different times of the day, revealing the interaction of light with the sculpture he made.

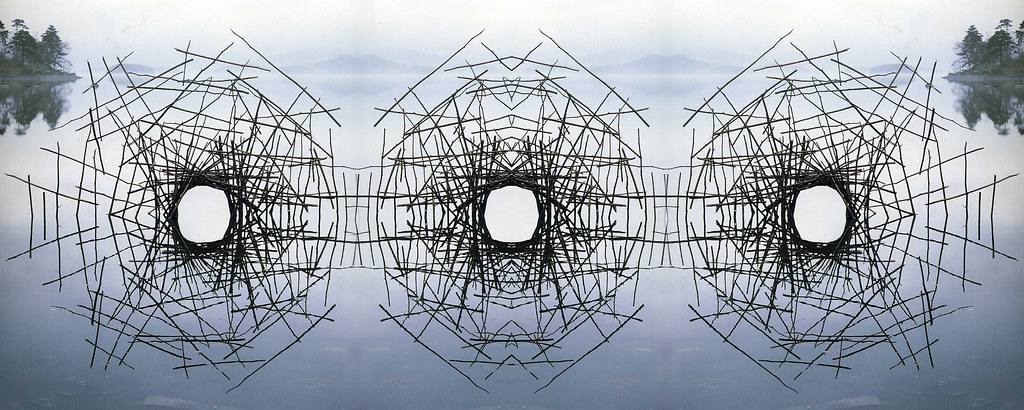

For the construction of Sticks Framing a Lake (7.8.12), Goldsworthy had to stand in the cold waters to build the structure. He gathered sticks and twigs from the surrounding areas. The dark sticks provided a perfect frame and contrast for the lake, altering the water's appearance. The placement of the sticks was difficult because they had to hold each other in place. Goldsworthy did not use any ties or other artificial material, only the sticks woven together. Although it appears the complete circle is sitting on top of the water, the bottom part of the structure is anchored in the mud of the lake. The circle reflects off the lake water presenting a complete image. If the light was in a different position, the reflection might look quite different.

Growing up in Scotland, Goldsworthy spent a lot of time in his younger years replacing the ancient stone walls found in the countryside. The walls were always dry-stacked stones, and he frequently used stones in many of his different sculptures. One of his first major commissions was constructing the stone wall Storm King Park (7.8.13). Originally, Goldsworthy planned to build a 237.7 meters long wall through the woods using the British tradition of stone-stacked walls. However, it was logical to continue the wall down to the pond when he came to an end. After Goldsworthy reached the pond's edge, the wall was extended again, across the pond and uphill to the roadway for a total of 694.3 meters. Some of the stones he used were remnants of an old collapsed wall in the woods. To construct the wall, larger, chunky stones were placed for the foundation, and smaller, rounder stones were built up the middle of the wall. Flat stones were used for the cap of the top layer. The team working on the wall had to chip small parts of the stone to ensure a tight fit. Goldsworthy believed the stone walls of different places connected the past to the present and the region's history.

Burnt Patch (7.8.14) is constructed from pine branches Goldsworthy had trucked from the trees of the Sierra Nevada. He burned some of the sticks to use in the center portion of the sculpture. The work was installed on a museum floor, unusual for Goldsworthy, who generally builds his work in the natural surroundings of a site. Each stick was installed in a precise pattern of a single layer; the charred sections in the center appeared as a hole.

The Cairn (7.8.15) was a recurring theme Goldsworthy used for sculptures, incorporating stone, branches, or even ice for different installations. Sometimes the cairn was more permanent, and others lasted only a short time. The stone cairn appears solid and long-lasting; however, even stone objects can collapse over time. Each stone in the cairn was hand cut to fit in place, most of the selected stones flat in appearance. For this cairn sculpture, Goldsworthy imported the stone from a local quarry.

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) was born in Paris, France. Her parents originally had a gallery selling antique tapestries. When Bourgeois was still small, her parent started repairing antique rugs, filling in tattered areas. Bourgeois received a good education in design and color. In 1930, she went to the Sorbonne to major in mathematics. However, when her mother died while Bourgeois was in school, Bourgeois switched to study art. After graduating from Sorbonne, she also studied art at some Academies. When she married, they moved to New York City. In the 1940s, she began to make sculptures from wood and other materials like plaster and latex. During the 1950s and 1960s, she was severely depressed and spent significant time in psychoanalysis. By the 1970s and 1980s, she started working in bronze and making large-scale works.

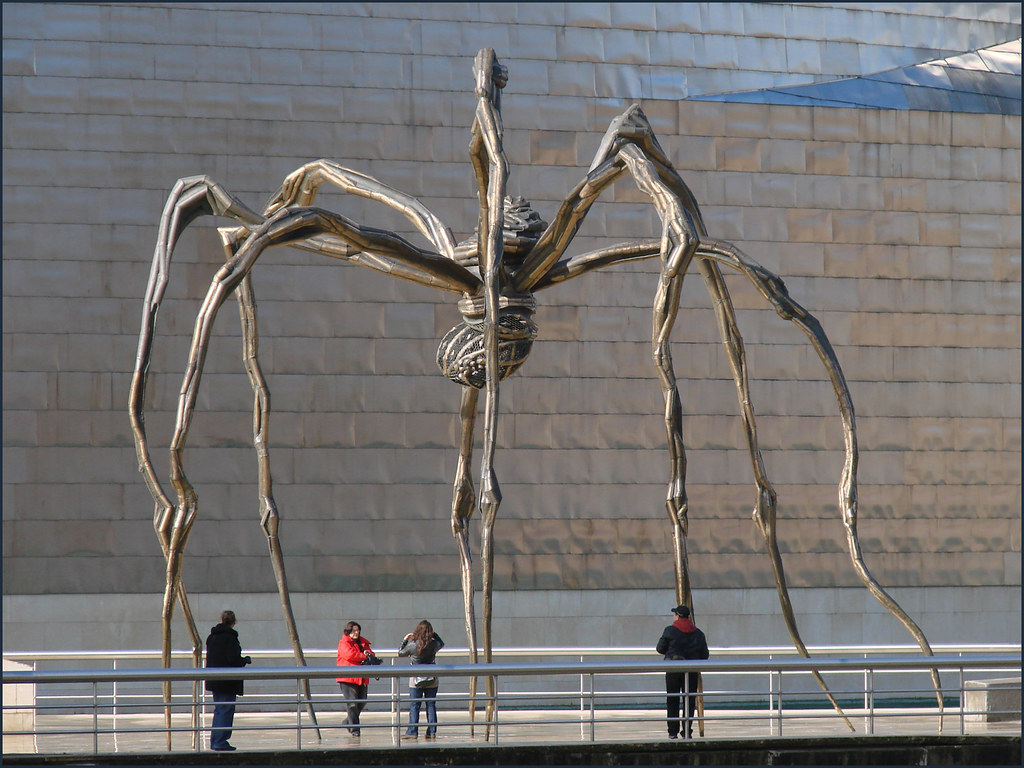

Maman (7.8.16) was one of her most famous sculptures, a larger-than-life creature and a scary image in anyone's dream. The bronze spider holds her eggs in part of her body; the massively tall spider is balanced on excessively long spindly legs. The sculpture is high above the platform, and viewers can walk through the legs and look up at the meshed sac holding the marble eggs.

Bourgeois made multiple spider sculptures in different sizes, and The Nest (7.8.17) created five different spiders, all standing under each other. Each spider has its distinctive body and long knobby legs. Bourgeois suffered emotional abuse from her father as a child, and her mother became her primary support. Bourgeois looked at the spider as a patient, methodical and valuable creature, reminiscent of her mother.

Eyes (7.8.18) is in a sculpture park in Oslo, Norway. The giant granite eyeballs sit by the water, the overly small pupils looking at the view. Some viewers see the sculptures as huge eyes while others infer them as two breasts. Bourgeois placed the balls on a small hill open for interpretation by viewers; are they accepted as eyes, or do they reflect the masculine perception of the female body.

Eye Benches IV (7.8.19) is installed in a park in New Orleans. The bronze benches have actual lights for the center of the eyes. Hurricane Katrina destroyed the square where the benches were installed, and when it was rebuilt, the benches were installed. Bourgeois made several different styles of benches from eyes, some in bronze and others granite. The various eye benches sit in their location, watching people walk by, viewers looking back at the eyes.

George Segal

George Segal (1924-2000) was born in New York after his parents immigrated from Eastern Europe. Segal's parents owned a chicken farm in New Jersey. He graduated from New York University planning to teach school. After he married, Segal and his wife also bought a chicken farm he ran. On the farm, he held picnics and invited friends from the university and the art world for performances while he taught art and English at a high school and Rutgers University. Segal started as a painter, and in 1961, he was given a box of plaster bandages to evaluate as an art medium. Segal took them home and made a cast of his own body, starting his career as a sculptor. Segal became a pioneer using the plaster-impregnated strips and created the process for using the material. He wrapped different parts of a model with the bandages until he had completed a whole body. After Segal assembled the sections, he added more plaster to the forms. At first, he left the sculptures in the original white color of the plaster bandages, and in a few years, began to paint them bright colors. Eventually, Segal cast the statues in bronze, sometimes adding a white patina to resemble the original form.

The Holocaust Memorial (7.8.20) was installed in San Francisco as a memorial to those who lost their lives during World War II in the concentration camps. Made of bronze and painted white, Segal constructed different symbolic meanings into the sculpture. The white, ghostly appearing bodies lie in piles, like the massive stacks of discarded bodies found in the concentration camps. One woman held an apple-like Eve in the bible, and another person resembled Jesus, connecting Jewish and Christian beliefs. Segal had his friends pose for the different people, so they did not appear emaciated as the corpses in the camps. The single person holding on to the wire fence is modeled after a photograph by Margaret Bourke-White of the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp. During the actual time of the camps, the wire was electrified to prevent escapes.

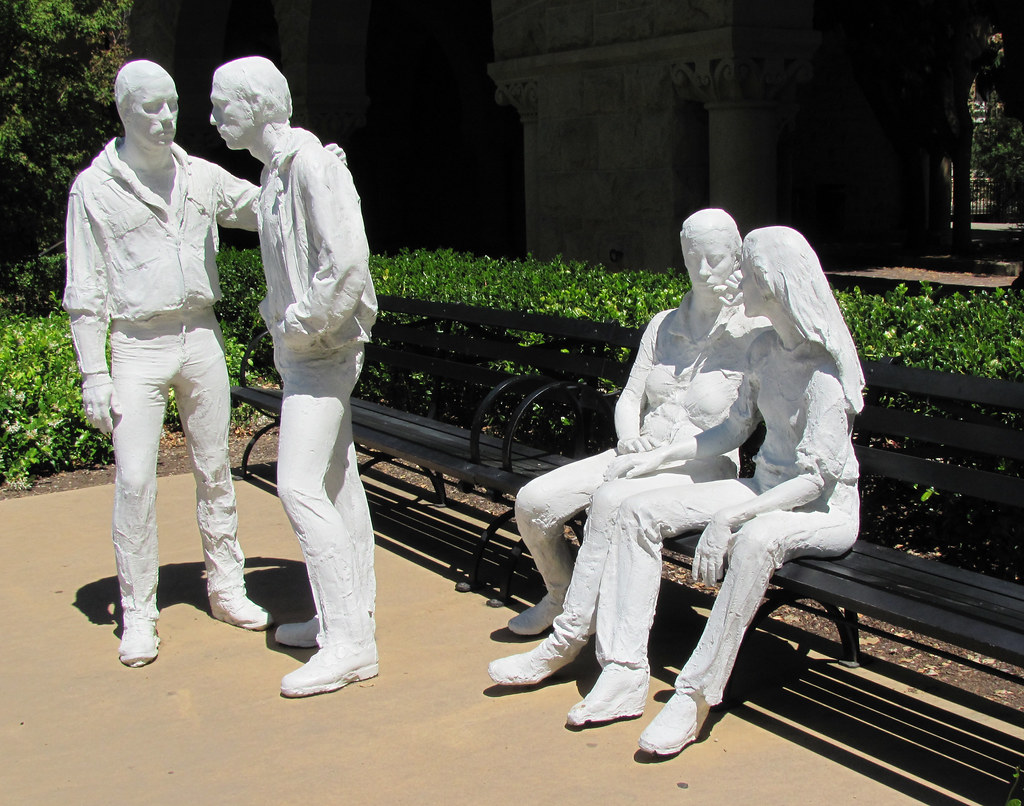

Gay Liberation (7.8.21) is part of the Stonewall National Monument in New York, and a second casting is installed at Stanford University in California. The four figures are made of bronze with a white patina, and two women are sitting on the bench while the two men are standing. The images of two gay men and two lesbians relaxing in a public place would have provoked controversy and derogatory reactions. Segal said of the finished sculpture, "it concentrates on tenderness, gentleness, and sensitivity as expressed in gesture…and makes the delicate point that gay people are as feeling as anyone else."[8]

The figures in Depression Breadline (7.8.22) stand slump-shouldered in nondescript clothing against the dark brick wall. The sculpture, in monotone colors, was a reflection of the alienation people felt during the depression. During the depression in the 1930s, one of every four workers was unemployed, and hunger and joblessness were common. People waited in long lines for food at soup kitchens, schools, or churches. The men in the sculpture are like the reality of the time, each person staring at the back of the other, no one engaged in conversation, each person isolated. Yet, they were all experiencing the same hunger issues, loss of jobs, and money. Segal dressed his models in the appropriate clothing and then wrapped the plaster bandages he dipped in the water around the model to make the sculpture. The person had to stand in place until the cast dried. The molds captured the folds, seams, buttons, and other clothing details. The molds became Segal's basis for using bronze to create permanent life-like images.

Hock e aye vi Edgar Heap of Birds

Hock e aye vi Edgar Heap of Birds (Born 1954-) is a Cheyenne and Arapaho native artist born in Wichita, Kansas. Heap of Birds holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Kansas and a Master of Fine Arts from (Temple University. He works in various media from drawing, painting, printmaking, glassmaking, but is known for his public installations and his powerful use of words. Heap of Birds grew up in Oklahoma and spent hours exploring the land, discovering the sharp stones. He thought about these stones as weapons, perhaps utilized by the Indigenous population 1000 years ago. The stones inspired his activism, fighting against racial injustice and Native American rights – not with sharp stones – but with art as his weapon.

In the 1980s, Heap of Birds started to make commercial-looking signs, placed on land not directly Cheyenne or Arapaho to recognize local tribes. The text on the sign Minnesota (7.8.23) stated in simple text, "ATOSENNIM TODAY YOUR HOST IS CLOUD MAN VILLAGE" the backward letters of Minnesota make the viewer decode the message and meaning. Basic shapes and colors evoke strong emotions conveyed through a few words. The present tense "today" underscores the native tribal population still here today. Heap of Birds created signs installed all over the country that defined the current name of the state and the Native American tribe originally inhabiting the area and, in many places, still there.

The sign Fighting Illini (7.8.24) reads, "INILLI GNITHGIF TODAY YOUR HOST IS POTAWATOMI" located in Illinois where the Potawatomi lived.

The installation, Building Minnesota (no pictures available) on the Minnesota River, came from an inspiration based on the gifts of the local native community in the Minneapolis area. He wanted to give back in a meaningful way. The site-specific work along the Minnesota River honors the 40 Dakota warriors hung in the United States' largest government-sanctioned death. Although 303 Dakota people received a death sentence after the end of the wars and forced relocation, only thirty-eight were ordered hung by Abraham Lincoln and two by Andrew Johnson. Heap of Birds created the installation with 40 signs. On the commercial-looking signs is text, which comes from letters written by Abraham Lincoln, each native warrior's name is spelled phonetically, for example, Ma-ka'tal-na'-zin (One Who Stands on the Earth). The text also states, "death by hanging on the order of Abraham Lincoln." This site became a place to honor those killed. Tribal citizens visited the site and left different items, sweat lodge bundles, and feathers. The Dakota Wars, which led to these deaths, was over the land; the United States government wanted more land to grow wheat and fought the Dakota tribe to force them off the land. The artwork educates people who don't know about the hangings or want to face this shameful part of history.

In 2005, Heap of Birds installed Wheel (7.8.25), a complex work of art with ten vertical forms in the shape of a fork. They represent abstract versions of fork trees used to build ceremonial lodges. The circle form is based on the Big Horn Medicine Wheel, a sacred site in northern Wyoming, and the circular shape of a traditional Plains Indian Sun Dance lodge. These lodges were made with 12 fork trees, and the forks became powerful structural devices to hold up a structure. The circular format also reflects the Medicine circle. The sculpture also underscores the astronomical science used by indigenous tribes. The artist only used ten vertical trees because he didn't want to construct a religious idol, only create art. Heap of Birds explained, "I was sensitive, very worried about overreaching my knowledge and divulging too much of it, to make a ceremonial instrument, so I removed two trees, so it doesn't function like the medicine wheel does."[9]

Figure \(\PageIndex{25}\): Wheel (2005, steel, enamel, 15.2 meters in diameter) by designsbykari, CC BY 2.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{25}\): Wheel (2005, steel, enamel, 15.2 meters in diameter) by designsbykari, CC BY 2.0The fork at the top (7.8.26) is usually where the lodge rafters are positioned in a ceremonial lodge. Without rafters, Heap of Birds wanted visitors, especially natives, would finish it in their imagination. The circle of bright red trees beckons visitors to interact with them. When the viewer reads the text, the artist's message about how the government massacred or reneged on treaties is understood. The artist wanted to display and expand the history and stories of Native Americans with more challenging dynamics. For example, the text on one tree states, "1864 Sand Creek Massacre," or "1868 Washita River Massacre". Heap of Birds family emblem, the Magpies, was based on his great-great-grandfather Many Magpies, who was imprisoned in the Fort Marion Prison. The image of Magpies covers one of the trees. Through text and symbolic imagery, Heap of Birds makes sure to involve the different types of viewers in seeing, reading, and understanding the artist's powerful message.

Viola Frey

Viola Frey (1933-2004) was born in California and received her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the California College of Arts and Crafts. Other students included Richard Diebenkorn, Manuel Neri, ad Nathan Oliveira, all active in the Bay Area Figurative movement. Frey went to New York to study at the Clay Art Center, where artists can investigate using ceramics beyond the usual constraints. She returned to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1960 and became one of the most respected ceramic artists. Her ceramics were based on enormous figures made from clay and painted bright colors. Some of the figures were almost 3.5 meters high, their immensity requiring her to create the entire sculpture starting at ground level and building up the figure. After the details were completed, the figure was cut apart to be fired and then reassembled like a jigsaw puzzle. Frey frequently portrayed the men in suits and ties and her female figures either nude or in patterned 1950s styled dresses. Although her specialty was immense ceramic figures, Frey also created paintings, drawings, photography, and work in glass. Her favorite art forms were miniature figurines she collected at flea markets. Frey took many of the smaller pieces and created assemblages of the parts. From the assembled components, she made molds to cast her sculptures made from amalgamated pieces,

Man Kicking the World (7.8.27) is dressed in a conventional suit of blues. Frey used red on his tie and face to dominate the otherwise bland person. He is looking at the world with his foot, ready to push the oversized world, only sensing some hesitancy about what might happen. She generally had men wear blue suits, portraying them as respectable and a symbol of power. The men were often seated or perhaps falling to demonstrate their vulnerabilities.

As seen in Homage, Frey did a small number of nude men and depicted them as vulnerable figures (7.8.28). She started the series in the 1980s when the Aids epidemic was rampant, and her assistant lost his life to Aids. Frey commented on her nude males, "I think I saw them as figures of vulnerability. How vulnerable people really are. Especially the men, who were on such a crest in the sixties. Come crashing down to all of this. It doesn't seem quite right."[10] Frey also treated the surface differently, the body covered in gashing white and orange intersected by yellows and blues. Her unusual use of color demonstrated her deep feelings about the subject.

Woman with Elbow on Raised Knee (7.8.29) is sitting in a relaxed position of self-assuredness. Frey always portrayed women as in control and alert, aware of their surroundings. She used blue to define the shadows as well as connections. The woman is well-groomed, her red nail polish and lipstick in place, her hair carefully combed even though she has no clothes. Regardless of how large or positioned they were, Frey also maintained the look and feel of averageness in both men and women.

Liliane Lijn's

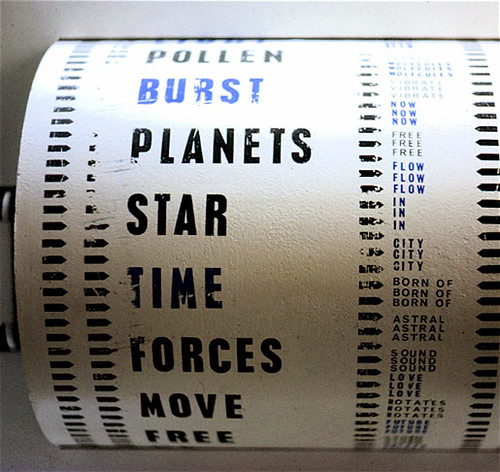

Liliane Lijn's (1939-) mother came to New York City from Belgium, and Lijn was born four months later. They were European Jews who were escaping the beginning of the wars. When she was fourteen and Europe recovered from the war, the family moved to Switzerland. Lijn studied archaeology and art history in Paris, hanging out in cafes and discussing poetry when she started to draw. She was always interested in different materials and experimented with plastics and how it reflected light or moved. Her first idea was the Poem Machine, where she combined her love of poetry and experimental sculptures. The words in the sculpture (7.8.30) spin, blurring, and vibrating. Lijn believed the power of words was diminished, and she wanted to change the visual expression of poetry into sound. She wanted people to see sound. While she was in Paris, Lijn also noted the lack of women artists and started making forms resembling the power of females. Much of her early work was based on kinetic art, and she wanted to do more than make something move as she was very interested in the combination of art and science.

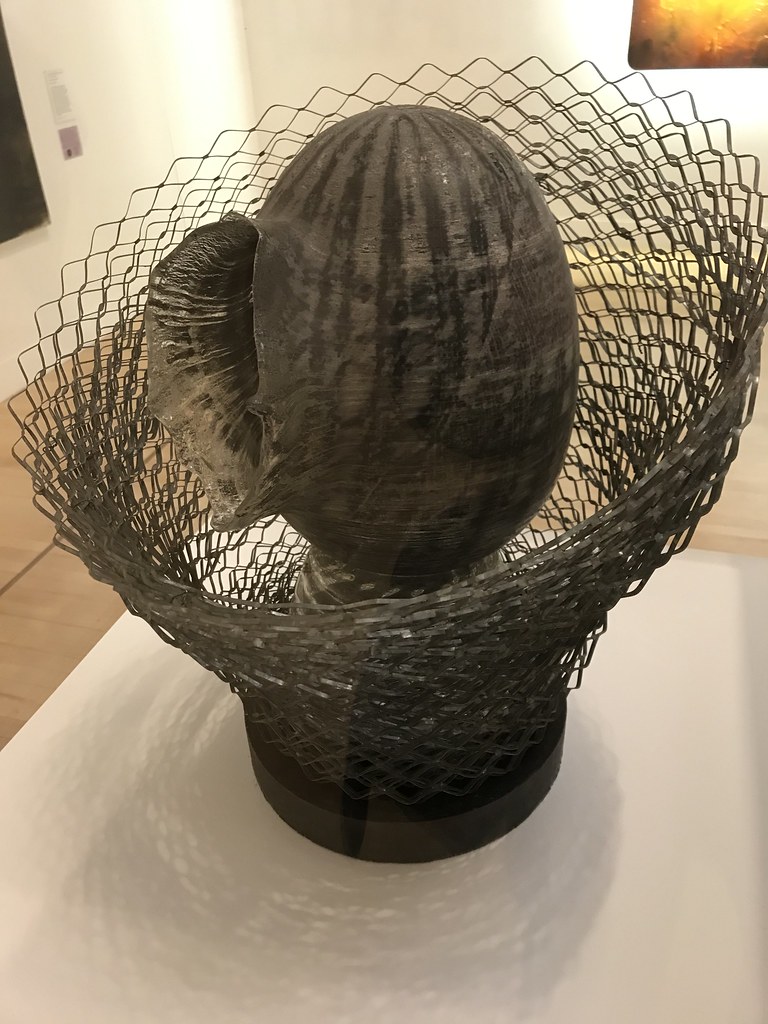

Armoured Head (7.8.31) is a small sculpture Lijn made with wire mesh formed to surround a sphere. The wire becomes looser as it progresses upward, leaving a large opening at the top. In the center, the sphere is zinc blown glass with vertical lines. She made a series of different glass heads using the blow torch to create wounds on the head. Blowing glass was natural for Lijn as she used the scientific tools on her sculptures to display pain and suffering. Part of her investigation of glass was how light and the color spectrum reflected and changed the glass.

Extrapolation (7.8.32) was a sculpture Lijn created based on the concepts of a book and the layers of pages in a book, a continuation of her interest in words. The sculpture's layers of plates were held apart by spaces to allow light to flow through and a feeling of openness.

When the light shines on the panels (7.8.33), they reflect the sky, appearing as one piece.

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff (1935–2020) and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon (1935-2009) became well-known as Christo and Jeanne-Claude, many people never knowing the artists' last names. Christo, born in Bulgaria, and Jeanne-Claude, born in Morocco. Both were born on June 13, 1935, and they met and married in Paris in the 1950s. Christo was interested in art in Bulgaria as a child, his education interrupted by World War II. After the war, Bulgaria was part of the Soviet umbrella and totalitarian rule, which suppressed and concepts of Western art. Christo did attend Sofia Academy of Fine Arts, finding the education very limited and dull. He was forced to paint propaganda and serve in the military during the summer. Christo decided to escape and stowed away on a railcar to Vienna, where he surrendered his passport to register as a stateless person and become eligible for political asylum. By 1958, he used his connections to go to Paris, where he met Jeanne-Claude.

Jeanne-Claude's father was a French army officer stationed in Morocco, where she was born. Her mother divorced shortly afterward and married three more times. Jeanne-Claude graduated from the University of Tunis, her degree in Latin and philosophy when she returned to Paris. She met Christo when he was painting a portrait of her mother, who was married to a French army general. Jeanne-Claude was engaged to another man when she became pregnant by Christo. She married the other man, left him on the honeymoon, and returned to Christo, their son born in 1960.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude created grand projects, always temporary and requiring support and approval from hundreds of people, including those who owned the land, the elected officials in every community, environmental laws and officials, engineers and designers, court systems, and the residents. They began by identifying their projects with drawings, photographs, material investigations, and how we would do this. The hardest part was approval for the seemingly impossible, grand-scale projects. The artists paid for all the expenses of the massive and large projects. They supported the project with sales of preparatory drawings, scale models, lithographs, and prints from earlier works. They did not take money from sponsors or community groups. Christo told the New York Times, "For me esthetics is everything involved in the process – the workers, the politics, the negotiations, the construction difficulty, the dealings with hundreds of people. The whole process becomes an esthetic – that's what I'm interested in, discovering the process. I put myself in dialogue with other people."[11]

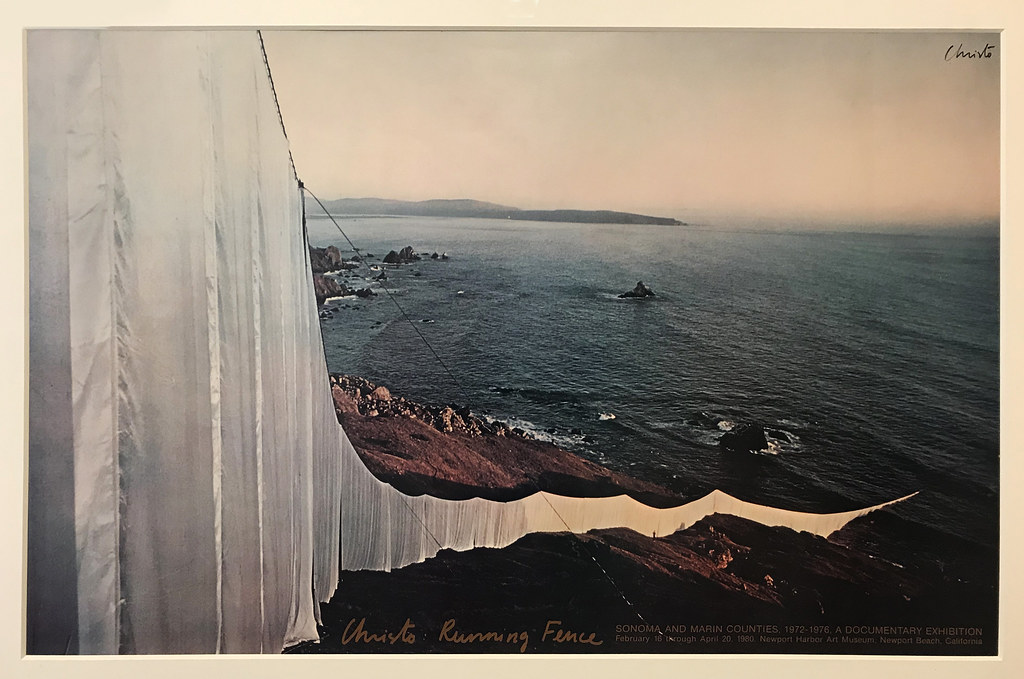

Running Fence (7.8.34) was installed near Highway 101, north of San Francisco. The fence ran along on private property over the rolling hills until it met the Pacific Ocean, almost forty kilometers. The fence was one of the early massive projects Christo and Jeanne-Claude created. The preparation took forty-two months working with ranchers, holding eighteen public hearings, writing a 450-page Environmental Impact Report, and three sessions at the Superior Courts of California.[12] Running Fence required 200,000 square meters of nylon fabric with 2,050 steel poles holding the cables. The poles were driven into the ground without any concrete as all the parts were made to be removed without any remains from the fence construction. Because the fence crossed roads and a town, they left passageways for cars, cattle, and wildlife. Running Fence was installed and removed fourteen days later; the artwork was installed for two weeks.

The Pont Neuf Wrapped (7.8.35) is a significant bridge in Paris, France; they wrapped in 1985, a complicated undertaking without obstructing the river traffic. The bridge was enclosed with golden, woven polyamide fabric. The fabric-covered all the bridge's parts, the sidewalks, streetlamps, and part of the embankment. Pedestrians walked on the fabric to cross the bridge. The fabric was held in place with thirteen kilometers of rope and twelve tons of steel chains, including a meter of chain underwater. The bridge was transformed, and different bridge details, usually not noticed, were suddenly interesting parts. The artwork was in place for fourteen days.

.jpg?revision=1)

In 1991, as the sun rose in Japan and California, workers opened 3,100 umbrellas simultaneously. The works were designed to reflect the differences between the ways of life and land use. The valley in Japan was nineteen kilometers, and the valley in California was twenty-nine kilometers long. The umbrellas were made from fabric with an aluminum frame on steel bases. 1,340 blue umbrellas (7.8.36) were installed in Japan, and 1,760 yellow umbrellas (7.8.37) were mounted in California. The umbrellas were colored and positioned to reflect the use and availability of land in each space. In Japan, space is limited, and the umbrellas were grouped closely along with the rice fields. The blue of the umbrellas reflects the plentiful water of the region. The umbrellas were spaced far apart in California, moving along the hillsides and valleys of abundant uncultivated land. Blond grasses covered the hills, an arid landscape, the yellow color of the umbrellas blending into the hills. In both locations, the umbrellas were visible for eighteen days, and the public could drive by or walk and sit under the shade of the umbrella.

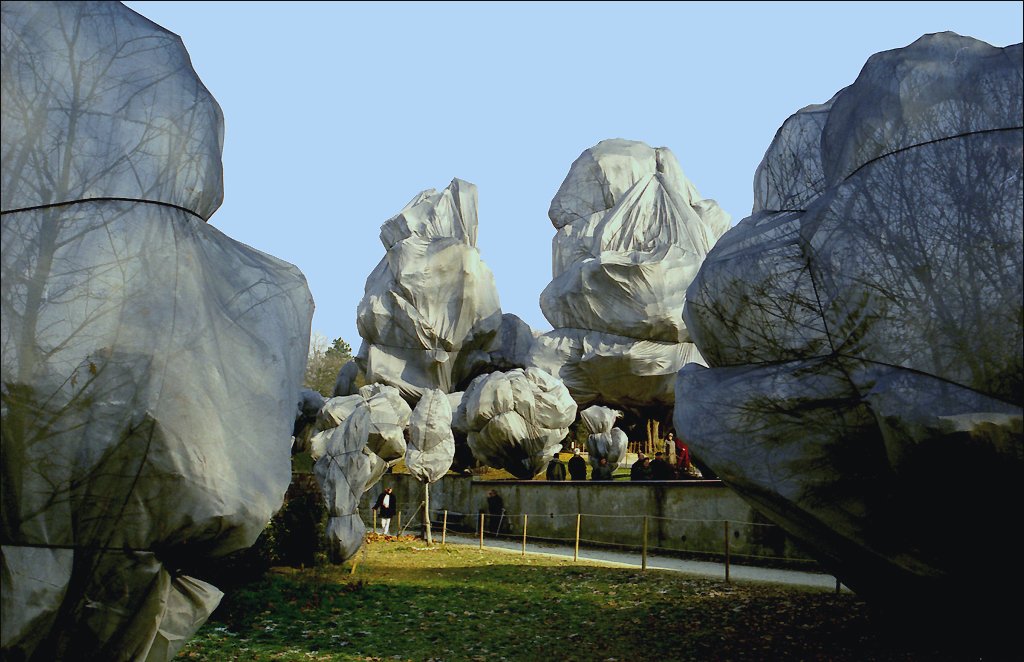

In a park in Switzerland, one hundred seventy-eight trees were wrapped with 55,000 square meters of polyester fabric and tied with 23 kilometers of rope. The Wrapped Trees (7.8.38) project took seven days in 1998. The trees were different heights varying from two to twenty-five meters. The installation was in place for two weeks, and when the wrapping was removed, all the material was recycled. The material was translucent, and the branches and leaves were visible through the fabric, changing the views as the wind moved the fabric into different positions. The trees were scattered throughout the park and along the creek.

The Gates (7.8.39) was an installation in Central Park, New York City. Along the pathways and sidewalks, they installed 7,503 fabric panels, each 4.87 meters high, 2.1 meters off the ground, and 1.68 to 5.48 meters wide on twenty-five different walkways.[13] The saffron-colored panels were suspended from the gate, the bright color visible from far away through the leafless trees. The poles were attached to paved surfaces, so they did not disturb the ground. The rectangular gates matched the shapes of the buildings. However, the gates moved along the serpentine walkways through the tree branches, a meeting of the organic forms mixed with static geometry. The warm saffron-colored gates almost appeared as golden meandering through the trees.

[1] Retrieved from https://racstl.org/public-art/joe/

[2] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81514

[3] Retrieved from https://catalogue.swanngalleries.com...3&refNo=593423

[4] Inglot, J. (2004). The Figurative Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz: Bodies, Environments, and Myths, University of California Press, p. 28.

[5] Retrieved from https://www.nashersculpturecenter.or...artist/id/3831

[6] Retrieved from https://crownpoint.com/artist/katsura-funakoshi/

[7] Retrieved from https://www.livingyourwildcreativity...y-1-mitchell-1

[8] Retrieved from https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/news/endu...ge-segal-ba-49

[9] Heap of Birds, Edgar. “Artist Talk: Edgar Heap of Birds.” Artist Talk, June 24, 2017, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN. Lecture.

[10] Retrieved from https://www.bonhams.com/auction/2610...omage-1985-87/

[11] Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/a...isto-dead.html

[12] Retrieved from https://christojeanneclaude.net/artw...running-fence/

[13] Retrieved from https://christojeanneclaude.net/artworks/the-gates/