2.7: Native American (1600 – 1800s)

- Page ID

- 121460

Introduction

What is Native American art? Unfortunately, the past stereotypes still prevail; a warrior with his feathered headdress or a woman in a beaded dress, etc., images perpetuated today by media practices, the educational systems, and individual perceptions. Native groups lived across North America and were as diverse in languages, traditions, rituals, and artwork as any population of people covering a large geographic area. With any populace in the world, their artwork was created using materials found in the people's location and culture. The art of Native Americans was deemed "primitive," and cultural artifacts as viewed through the lens of the invading populations. Art, sacred objects, and human remains were taken and moved to unknown places and displayed as curiosities. The rightful status of the artwork was not acknowledged; much of the sacred meanings created by people for their own cultures were lost.

This book uses the name Native American to discuss the artwork. Other terms might include Indigenous, First Nations, First Peoples, American Indian, all of which are generic names and only identify a location as North America, not individual cultures. From the 1600s – 1800s, the cultures were generally grouped into geographic designations (2.7.1); Arctic and sub-Arctic, the Northeast Woodlands, Southeast, Plains, Southwest, Great Basin, California, Plateau, and the Northwest Coast. Patterns of art in a unique section were similar because of materials available in the area; for example, the particular type of clay in a given area defined the style of pottery, or the type of indigenous animals determined how clothing was made and its ornamentation. After the 1600s, artwork in every area was also influenced by the effects of European invasion and colonization.

In many other cultures, an artist's concept was based on the wealth and support of the elite, royalty, and religious leaders who employed artists to produce art for religious or commemorative reasons. Although records do not exist for individual artists in early Native American cultures, surviving art demonstrates a person's talent who made a beautiful, well-formed carving versus a poorly made version. Generally, decorative elements of their design were based on natural forms or geometric shapes, and the style of a particular artist might be found if more than one version of a piece of art survived.

Arctic

The Arctic region is flat with trackless tundra, cold and dark with little vegetation. The population of Inuit and Aleut people was small because of the inhospitable land, living in scattered groups as nomads or small villages along with the ocean areas. Weather ranged from the dark, frigid winters, the rainy seasons to the hot summers of long days and forced the people to be resourceful, using limited land resources. However, the oceans brought abundant food sources; shellfish, whales, salmon, seals, other sea life, and birds of all varieties. Hunting was risky, the ice and seas unforgiving. The materials available for art were based on the sea and animals; using driftwood, bone, skin, or fur, they made smaller objects portable for use in everyday life or ceremonies.

Clothing for winter was made from the fur and skin of the local animals; however, the most effective material for protection from the weather was the gut garment (2.7.2). They were made from the intestines of the large sea mammals or the bear and decorated with feathers, fur, or other found materials. The intestinal tubes were cleaned with scraping tools; the gut was blown up, stretched into a straight line, and left to dry. If the gut was dried in the winter when it was cold and dark, it became white and known as the 'winter gut.' A gut dried in the summer with warmer days had a yellow hue called the 'summer gut." When the gut tubes were dried, they were cut lengthwise into long strips, ready to be sewn together. Sinew was the typical material used for sewing, and then the garment was embellished or left plain. "In all traditions, the making of a gut garment is considered a gift to the animal whose flesh served to provide such an excellent protection from the elements. Each parka is constructed with care and honor from the hunter and for the animals he has received and will gather for his family."[1]

The Aleut were known for their carvings, passing the long winter nights making weapons for hunting, images of animals and people, or sewing needles and jewelry. Their houses were partially subterranean, small dwellings of driftwood with sod roofs, the dark interior lit by the fat from sea mammals burned in small stone lamps. Ivory from the massive walrus was the favorite material to use, and driftwood washed up on the beaches for carving with chipped stone tools. The carving of the small (7.8 centimeters) seated female (2.7.3) with her knees folded up to her chest was made from the walrus' tusk. The miniature objects were easy to transport and generally used as fetish figures or storytelling.

Sub-Arctic

Mostly Algonquin-speaking people (Cree, Ojibwa, Naskapi) inhabited the Sub-arctic region and followed a nomadic life into the 19th century. Archaeologists believe they had the longest uniformity of cultures of the native peoples and, until their initial contact with Europeans, followed their traditional lifestyles for over 7,000 years.[2] The land stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific across mountains, tundra, and forests. The weather was too extreme to grow crops, and they remained dependent on the bountiful natural flora and fauna for all aspects of their lives. The people generally lived in small groups; however, travel was possible across flat tundra and the multiple rivers and lakes. A variety of artwork was developed in different areas based on natural resources available and later materials brought by Europeans. Initially, they may have used moose hair to sew and embroider designs on clothing or porcupine quills for baskets. The traders who came brought glass beads, and women artists wove the beads into their designs.

Bandolier bags were based initially on the bags the soldiers from Europe used to carry their ammunition, a concept adopted by multiple Native American groups across the Sub-arctic and Northeast regions. Men wore them with the wide strap across the chest and the bag section resting on the hip, not intended for battle, rather as decorative elements and part of ceremonial clothing. Women made the bags, and the early ones (2.7.4) were generally made from native-tanned leather for the base and decorated with porcupine quills which were softened, dyed, and then bent into the required shape. White quills form the zigzag pattern across the bag and the stripes on the handle. Deer hair, yarn, and natural fibers were added to complete the bag.

The later bandolier bag (2.7.5) demonstrates the influence of trade with the Europeans and the acquisition of glass beads, yarn, and ribbons. The women artists changed from porcupine quills to glass beads, adopting new ideas to decorate their clothing and bags with different colors and techniques. The patterns were intricate, the beads reflecting light and the ribbons moving in the breeze.

The Naskapi coat (2.7.6)was based on different styles of European coats and the design and needs of the Naskapi artist. They used colors from natural products, which were ground into powder and mixed with a binder. The proteins and lipids from salmon eggs made a suitable binder with the pigment. The fish egg acted much like the egg tempera used for the frescoes of civilizations along the Mediterranean, a durable process.

Together, the female artist and the hunter who would wear this coat conceived the geometric, colorful design based on the man's dreams of the motifs that would give him power and ensure his success in the hunt. Coats such as this example were worn for only one caribou hunting season, as the Naskapis (Innus) believed they lost their protective power over time.[3]

Northeast

Although prehistoric art existed in the region for thousands of years, early contact with European explorers and settlers from the 1600s onward changed the concepts of indigenous art. Different explorers, missionaries, and settlers wrote about, sketched, and unfortunately "collected" art and arbitrarily defined cultural characteristics. "But this emphasis has resulted in a frozen time perspective and an erroneously narrow view of the great historical depth, diversity, and richness"[4] of the art history existing in pre-contact Native peoples.

The Iroquois-speaking people (Oneida, Seneca, Erie, etc.) inhabited the northern part of the region and were most affected by the invasions of people from Europe. Algonquian-speaking people (Pequot, Shawnee, etc.) lived in the southern sections. They had farms and permanent villages and based their artwork on their social institutions. The European colonists forced the different groups to fight against each other, taking sides in the European battles to control the territories. By the early 1800s, most native peoples migrated to the west or were forced to leave and be resettled in other areas. After the 1600s, the contacts from the Europeans changed the economy of the Native Americans, who had established trading partnerships. As the European incursions expanded and territory was seized, the local economy was severely disrupted. By 1800 the native populations were restricted to reservations, and their lifestyles changed forever. The wooden comb (2.7.7) was made from a moose antler, a common material since the moose shed their antlers yearly in early winter and grow a new set in the spring. The carved comb depicts two Europeans dressed in coats and hats and may have been made for trading.

Both male and female Iroquois wore moccasins (2.7.8) made from one piece of deer or elk skin, which was smoked, creating long-lasting and sturdy leathers. The moccasins had a seam in the back for the heel and one in the front across the top of the foot. The bottom was flat, comfortable, and durable. Around the ankle, the sides are folded down a few inches for the cuff and decorated. Initially, the decorations were made from porcupine quills, and after the Europeans came, they used glass beads. Sometimes the beadwork was sewn on a separate piece and then attached, and when the moccasins wore out, the beadwork could be removed and used on a new pair.

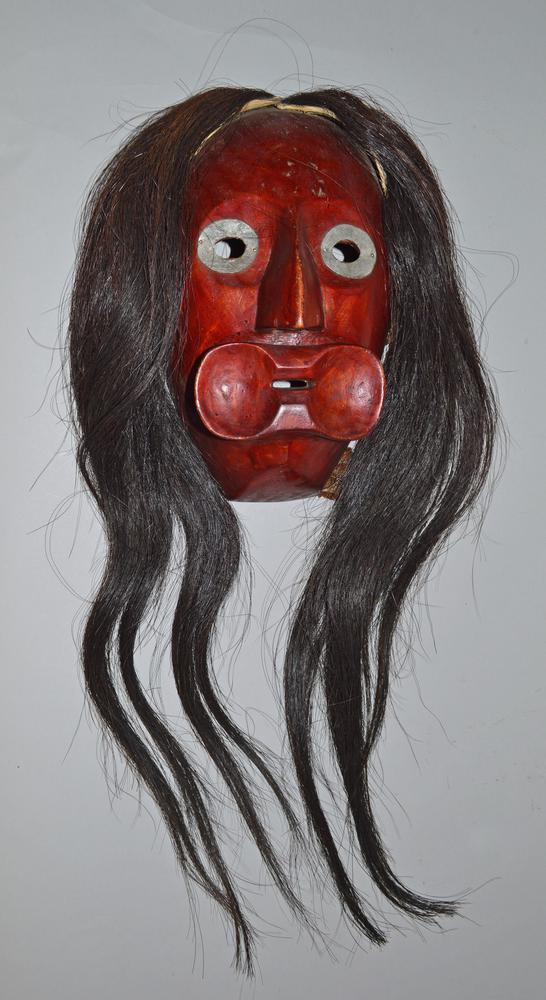

The False face mask (2.7.9) was used during ceremonial and healing rituals. Different types of masks were made for each of the ceremonies based on the type of illness a person was suffering from and which spirits needed to be driven away using the appropriate mask with an exaggerated nose, no eye sockets, or a distorted mouth. The mask creator searched through the woods until he came to a tree representing a spirit and carved the wooden part of the mask from that tree. Masks were painted red if they were created during the morning or black when they started in the afternoon. Horsetail hairs were used for the masks, and before the Europeans came, they used corn husks.

Southeast

The Southeast culture was based on agriculture in the fertile region, growing maize, tobacco, and beans. Living in villages, their houses, burial sites, religious sites, and storage facilities were frequently constructed in the shape of mounds. They each developed hierarchical societies with powerful chiefs as rulers and those in leadership positions. From this area came names familiar today; Cherokee, Chickasaw, or Seminole, and others. Large numbers of people perished from diseases introduced by the European settlers, and by 1830, only about 100,000 Native Americans lived in the territory. However, the European colonists wanted to expand their farms to grow cotton. The Indian Removal Act forced the relocation of most of the native people into the plains areas, a journey called the Trail of Tears, reflecting on the human toll and misery of the relocation.

The lidded basket (2.7.10) was made from the canes growing in thick forests along the rivers. The river canes were gathered, and the hard-exterior parts split into strips, ready to be woven. The lidded basket has diagonal lines along the base, darker triangles around the sides, and rectangles decorating the top. Some patterns were based on the natural colors of the canes, and other strips were dyed with walnuts or berries to produce specific colors. Baskets were an important part of life both in mythology and practical uses in life.

Tobacco was native to South America and grown throughout the Americas, an important ceremonial plant for most native peoples. Tobacco grew well in this territory; however, if tobacco did not grow in a region, it was obtained from other people through trades. Tobacco was an integral part of ceremonies where smoke carried prayers to the heavens. It was also used as a medicine for multiple ailments, included in medicine bundles, and was smoked in social situations by both men and women. Depending on its purpose, the pipes used for smoking might be considered sacred during rituals or an everyday item. The pipe (2.7.11) was made of steatite or black pipestone. Originally a light gray in its natural state, steatite turns deep black when carved and polished with wax or oil. This stone was a common material used by Native Americans for their pipes, soft enough to cut and shape and hard enough to support intense heat.

Plains

The Plains area was a vast space across the country from the Rocky Mountains to the Mississippi, filled with mountains, plains, tablelands, and river valleys. Originally, the people were hunters or farmed in small communities, the regions filled with wildlife of all kinds. Many people moved throughout an area to follow the weather, water, fields they could cultivate, and animal food sources. When the Spanish came, they imported horses, and the local groups (Crow, Comanche, Arapaho, Sioux, etc.) used that resource to pursue the bison, adopting a more nomadic lifestyle. They made tipis from the hide of buffalos around lodgepoles, easy to assemble and move to follow buffalo or avoid danger. White traders' excursions into the area brought guns and disease to the people, and sport hunters exterminated most of the herds of bison until the people were finally forced onto government-run reservations.

Bison, deer, sheep, and antelope were abundant in numbers on the plains and the most important part for the life of the people, providing food and hides for their shelter, clothing, and other necessities. The thick, heavy buffalo skins were valuable as blankets in the cold winters, while the lighter weight and thinner deer and antelope hides were used for clothing. To make anything from the hides was difficult and complex. The men were the hunters, following the herds and bringing back the animals, and the women prepared the hides.

The women work to prepare the hides by removing the hair and tanning the skin. It is messy, hard work and requires muscles and brains—the muscles of the women, and the brains of the animal! In one tanning method, the hide is first soaked in water mixed with ashes for several days. Then it is put on a wooden frame and the hair is scraped off. Next, cooked brains of the animal are applied to the hide in order to soften it. The hide is then rinsed and stretched and pulled until—as one dressmaker says—your arms are "so tired, they feel like they will fall off!" This process is referred to as "brain-tanning" and is still done today to prepare hides that will be made into dresses, shirts, jackets, purses, and other items.[6]

The people of the plains regions have a history of decorating their clothing and other articles. Before the Europeans brought glass beads, they used paints, natural minerals, and fat from the plentiful bison. They found the hip bone in the bison very porous and able to hold paint, a useful tool along with grasses. Porcupine quills could be dyed for color, and other animal bones, teeth, or claws made attractive decorations or supported ritual meanings.

Made from native-tanned leather, the Sioux dress (2.7.12) was probably made for ceremonial purposes. The elaborate glass beading forms a bright blue background with meaningful symbols in green, yellow, red, and black beads across the top. The fringe was cut in small strips from leather as part of the sleeves and bottom and added to the dress, giving the woman another movement.

After the hide was cleaned and tanned, women adorned the clothing with sacred designs or symbols of life using paint or beads and porcupine quills. The robe (2.7.13) was tanned and painted with a traditional Arapaho design, a box-like structure in the middle filled with precisely painted triangular shapes. The outside edge is bordered by white and red lines reflecting Arapaho's use of dynamic colors.

All types and styles of bags were made and used throughout the different regions. The parfleche bag (2.7.14), made from hide, was shaped like an envelope used by men and women to carry pemmican or other dried foods. Each bag was decorated in an abstract style to symbolize the natural landscape of the plains, rivers, or hills or a family symbol. A hide was cleaned, tanned, and stretched into shape, then soaked and dried over a smoky fire to make the hide very hard. To make the design, the hide was incised, painted, and fringed.

The tobacco bag (2.7.115) was also made from hide and was used by males to transport pipes and tobacco for ritual ceremonies. The highly decorated bag was painted, then the hanging strips were covered with beads and horsehair.

Great Basin and Plateau

The people of the Great Basin (Shoshone, Paiute, Ute, etc.) lived in frequently barren areas and moved from place to place to forage. Their settlements were small, and housing was made from trees and brush, easily made and destroyed to move again. Horses from the Europeans gave them more mobility for a while; however, the discovery of gold and silver forced the people onto reservations.

The Plateau region was smaller, less populated, and people (Klamath, Nez Perce, Flathead, etc.) lived in villages by rivers and streams. Natural resources provided food, and they did not have to travel far to survive. When horses came to the area, they expanded their territory; however, when the Lewis and Clark expedition arrived in 1805, other white settlers followed along with diseases. After a gold rush, the government took over six million acres of land. It moved the Nez Perce to a reservation triggering further battles to retake their land, only to be pushed and shoved into smaller areas, losing their homeland. At the end of the 1800s, the people were removed from their lands onto small reservations.

As with other native people in the plains and plateau regions, the Nez Perce who lived in the plateaus fashioned their lives after the same types of natural resources as those from the plains. The invention and use of the blanket strip occurred during this period. The changes started on the plains and moved to the plateau, demonstrating the creativeness of the women. The giant bison was heavy and hard to manipulate when the women tried to cut the skins from the carcass that lay on one side. They learned to cut the skin along the backbone and remove the one side before rolling it over and removing the hide from the other side. When they were ready to tan the leather, they sewed the two pieces together to make a robe. However, this left them with a seam that showed, so they designed a blanket strip (2.7.16) to cover the seam. The blanket strip was decorated and was so popular; other ornamented strips were added even if they didn't cover a seam. The designs on the strips were symbolic, generally holding a sacred significance.

Southwest

Some of the native populations in the area were farmers (Hopi, Zuni, Navajo, and others) who lived in permanent settlements and farmed crops of corn and squash. They used the resources of the landscape and built multistory pueblos and ceremonial centers. Others like the Apache were nomadic, moving around the region, hunting and invading their neighbors' crops. The Spanish were the major European power in the region and exterminated many people in wars or enslaved them. Eventually, most of the remaining population was resettled onto reservations.

Native Americans in the Southwest have a long tradition of art, masters of weaving and pottery. The Pueblo people grew cotton and began weaving with a backstrap loom around 700 CE. The people stayed in the area, developing their skills based on the different natural resources available. Historians believe Hopi and Navajo weavers learned the skills from the Pueblo people around 1650, and each of them perfected their patterns, colors, and styles. Pottery was another art form highly developed in the area created on long traditions of techniques passed through the generations. Clay was abundant, and natural materials for paint were made by grinding rocks or using a wide variety of plants.

Kachinas were a specific form made by Hopi for use in religious practices, icons made from the indigenous root of the cottonwood tree. The Kachinas, used for generations, were carefully painted to resemble figures representing different aspects of mythology and religion. Kachina figures (2.7.17) are small. They resemble the shape of a human, carved, rubbed with sandstone to smooth the figures, then painted with pigments made from natural materials, ready to be used in ceremonial activities.

%252C_probably_late_19th_century%252C_04.297.5575.jpg?revision=1)

In the southwestern region, cotton was grown and an integral part of weaving to make clothing. When the Spanish came with their sheep, the Navajo adopted the techniques of producing wool, incorporating it as an important source of materials. Weaving traditions and patterns were reflected in the horizontal, diamond, and zigzag themes using vibrant colors. A significant item of clothing was the blanket. The striped wearing blanket (2.7.18) was woven with undyed wool, fleece dyed with indigo, and unusual raveled bayeta. During the Navajo trade with Mexico, they obtained a red flannel material named bayeta, a fabric getting its red color from a specific insect species. The Navajo stripped each of the fibers from the bayeta and re-twisted it into new yarn to use the material.

Later, blankets (2.7.19) were made with vividly colored yarns and patterns of diamonds, zigzags, and stripes, a contrasting single strand of yarn used to highlight the design.

Zuni women generally made the pottery, gathering clay, sifting it to remove impurities, and mixing the powdered clay with water. They used the coil method to shape the pots (2.7.20) and smoothed the sides with a handmade tool. The designs were based on clan designations and events in their life, painted with natural dyes and brushes created from the yucca plant, then fired in kilns. Firing the pottery followed a ritual, using respectful, soft voices or even silence; the women carefully placed the pottery on the fire, allowing the voice of the clay to emerge.

The Apaches moved throughout their region, not building permanent housing in the area, requiring lightweight and portable methods to store food and other items. They perfected basket making; a tradition passed from mothers to their daughters. Regional natural materials in trees, grasses, and roots were common to use in a basket. The large jug-shaped storage basket (2.7.21) could be waterproofed with resin from pine trees to hold liquids, or it might be used to store food or firewood. The basket was made from the shoots of the willow tree, root of the yucca, and a plant called the devil's claw, forming the intricate pattern based on symbolic beliefs. Frequently, the basket was carried on a person's back with a large strap across their forehead.

Northwest Coast

The climate of the Northwest coastal region was mild, and natural resources were abundant, especially from the ocean. Although they were hunter-gathers, they did not have to travel from place to place to survive; water sources provided a constant supply of fish, seals, and shellfish. They built permanent structures forming large villages and broad social networks. Europeans did not inhabit this region in large numbers until the late 1800s, so the native populations (Tlingit, Penutian Chinook, etc.) maintained their traditions until then. With the influx of Europeans, new diseases, and suppression of their social structures, the societies became fragmented.

The native people from the Northwest are known for their artistic traditions, design, and artistry. Many practices are formalized, and the "formline" became the primary design element that defines outlines and colors. The colors of formline painting were based on black lines, red lines, and additional blue and green tones. The different color pigments were mixed with dried salmon eggs as a fixative, and their brushes were usually made from porcupine hairs.

Artwork frequently defined kinship, spirit powers, or territories. Potlatches were ceremonial events to display objects of art and value. The crest had significant meaning, similar to heraldic art of England, portraying real and imaginary animals. The crests were added to totem poles, house fronts, or ceremonial clothing, a legacy from ancestors to descendants; the crest was a sacred object.

Most of the art was made by men who formed in groups and were supported by patrons. They made the crests, totem poles from the abundant trees; carved from whalebone, ivory from the walrus, or wood from the trees, natural materials were available everywhere for the artist. Natural forms of whales, eagles, bears, or other animals and spiritual or legendary creatures were used as patterns for their designs.

The grip of the Tlingit dagger (2.7.22) appears as an animal, staring with one eye made from a stone. The wooden carved face has deep ridges reflecting the early form line style. The techniques to forge iron are not documented; however, historians believe native smiths developed metalworking techniques well before the Europeans arrived. This dagger was generated from a whole piece of iron using the hot chasing process. Holes along the top of the head were pierced, and the eyes and spaces were between some teeth. Many historians believe the dagger was made by the female metal smith Saayina.aat because of its proportions and signature design. Most of the daggers had long blades, however, the blade of this one is broad and short, with two ridges down the sides, reflecting her style.[7]

One of the unique styles for weaving blankets was done by the Salish, who lived along the coast of British Columbia. Robes were made with a process called twining. In the usual weaving process, the single thread of the crossing or weaving weft stays perpendicular to the installed warp. Twining has a pair of weft threads that switch back and forth as they move along the warp threads, twisting the warp and creating the diagonal slant. The warp thread had to be sturdy to survive the twisting, and the Salish used nettles or the bark inside the cedar tree. The Salish robe (2.7.23) is made with natural dyed material of reds, blues, black and brown along with undyed yarns, all made with patterns of checkerboards, zigzags, geometric shapes, and lines.

The Tsimshian lived in British Columbia and Alaska, a matrilineal society with a clan system based on four different totems; the eagle, a wolf, a raven/frog, or the orca. A person belonged to their mother's clan, and the ceremonial chief could be male or female. The raven rattle (2.7.24) was a standard instrument for shamanic rituals, so the beak pointed towards the ground to guide the shaman. The figure has the face of the wolf, perhaps identifying the owner of the rattle. The rattle was carved in two different pieces, filled with seeds or pebbles, joined with wooden pegs, and then painted in traditional colors. An artist might adorn the rattle with feathers, beads, or other natural decorations.

California

In the late sixteenth century, it is estimated California had over 300,000 people with many different groups (Miwok, Pomo, Serrano, etc.), all speaking different dialects. The population was one of "the largest and most diverse in the Western hemisphere is exhibited by the no fewer than sixty-four distinct languages they spoke…Before white contact, California had more linguistic variety than all of Europe."[8] Despite the diversity of languages, most native Californians practiced similar live styles, organized around small groups as hunter-gathers who traded with each other. As the Spanish colonized California, they brought disease, forced labor, brutal religious practices, and nearly exterminated the native populations.

Basketry was the primary art form of the Native Californians, each varied according to the local group with different designs and uses. Baskets were used for "gathering food, sifting acorn meal, storing tobacco, gambling, cooking, and even transporting water. Native Californians could weave so tightly that their baskets held boiling water—heated by hot rocks—without leaking."[9]

The Chumash, who lived in the southern part of California, made the tray (2.7.25) of sumac shoots and juncus stems, forming a set of concentric circles of geometric shapes, alternating with a triangle pattern and parallel bars. The Miwok extended from the valley to the mountains through the state's middle and had many types of natural materials for their baskets. They could split small sapling trees into strips or use grasses like the carex barbarae root for the lighter colors.

Baskets were so well made and so familiar; making pottery was very rare.

A basket (2.7.26) incorporated dark brown or black using ferns or dyeing material with ashes, pulverized manzanita, or the bark of the black oak. The primary tool was an awl made from bone to pierce the material while making the tightly coiled basket.

The Pomo basket (2.7.27) from the northern part of California followed the tradition of including multiple patterns in the basket. A substantial portion of the design is the dau or spirit door to allow good spirits into the basket, made by leaving a small opening or turn in the stitching. The Pomo also had many natural materials available, and willow shoots, river canes, and sedge roots were the most common. The materials were cleaned and dried and, if needed, split or dyed. Males constructed baskets for fish and bird traps, while women made the baskets for food storage and religious rites.

By the end of the 1800s, most of the tribal lands were taken, and the Native Americans who lived on those lands for centuries were moved to reservations, splitting up tribal groups and customs.

Chief Joseph said in the famous statement attributed to him;

…My people, some of them, have run away to the hills and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun not stands, I will fight no more forever.[10]

The traditions of Native American art changed, and their art became a commodity, sold to outsiders and tourists, divorced from the people and its meanings. Many works by Native people were meant for sacred ceremonies, not displayed in museums. Today, in both the United States and Canada, a few museums are starting to honor these beliefs and remove sacred items or grave goods from their displays. There is still a market for different groups to recreate the art of the past for sale. However, today there is a resurgence in their artistic traditions by Native Americans in North America, bringing their cultural backgrounds into their modern styles.

[1] Reed, Fran, "Embellishments of the Alaska Native Gut Parka" (2008). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 127. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1127&context=tsaconf. 29 January 2019.

[2] Kopper, P. (1986). North American Indians, Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C. p.113.

[3] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collec...p=20&pos=1

[4] Vastokas, J., History of Indigenous Art in Canada (2018). In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia....-art-in-canada

[5] https://books.google.com/books?id=uh...ensils&f=false

[6] National Museum of the American Indian, A Life in Beads: The Stories a Plains Dress Can Tell,

Retrieved from https://americanindian.si.edu/sites/1/files/pdf/education/NMAI_lifeinbeads.pdf

28 January 2019

[7] Torrence, G., (2018). Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[8] Retrieved from https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=23548

[9] Retrieved from https://calisphere.org/exhibitions/e...pre-columbian/

[10] https://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/peo...hiefjoseph.htm

[11] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plai/hd_plai.htm) (20 April 2020)