1.9: Early Colonial Latin Americas (1521-1600 CE)

- Page ID

- 120730

Introduction

Christopher Columbus voyaged to the Americas several times between 1492 and 1502, inspiring other explorers to seek fame and fortune. Columbus initially landed in the city of Santo Domingo, the Dominican Republic. He believed he discovered the Indies and named the indigenous population "Indians." This term is controversial today; some scholars continue to use the word, especially in the discussion of history. Indigenous and Amerindian are other terms currently used to describe the native people of the Americas.

Taíno is specific to describe the Indigenous cultures of the Caribbean, the people Columbus encountered. The Taíno community did not consistently focus on the arts because the chiefs did not demand goods and services from their people. However, a few of their exciting crafts of pottery and carvings were considered "minor arts" by the Spanish. One surviving element was a vessel decorated with spirit faces, called a zemi figure (1.9.1), used in the ritual of ancestral worship. Since these objects were used in a pagan form of ritual worship, the Catholic Spanish conquerors destroyed many of these objects. However, some of these unique vessels survived the conquest simply because the objects were considered "curiosities."

_MET_DP295635.jpg?revision=1)

By 1496, Spanish missionaries and colonists permanently settled in the Caribbean. Conquistadors from Spain made their way to the Continental Americas to discover their wealth and prove their military strength in the conquest of Latin America.

The Colonial Era

In Europe around this time, Michelangelo was working on his monumental statue of David. Leonardo da Vinci used his knowledge in the arts of anatomy and science to inform his works of art, and Raphael was creating the beautiful paintings of the Vatican. Beyond the High Renaissance in Italy, the Mannerist style of art emerged as artists focused on deception. Artists in the High Renaissance tried to disguise their works of art by creating illusionistic scenes. Mannerists focused on the unreality of the world presented by emphasizing deception. Subsequently, Mannerist artwork found patrons of high social status. The letterpress, discovered in Germany, allowed artists to match the printing press's advancement and technology with graphic art mediums, including woodblock prints and engravings. Artists from Flanders were also advancing arts by creating highly realistic works of art with the newly discovered forms of oil paints. Large altarpieces in both Flanders and Spain assisted the Catholic viewer in understanding complex doctrines. Known for his reconquest of Spain from the North African Moors in the name of the Catholic religion, Flanders came under the control of Charles V of Spain in the 1500s. In 1517, the Reformation was sparked by Martin Luther, leading to a split in the universal Christian church into Protestantism (the reformed religion) and Catholicism. Spain was profoundly Catholic, and Charles V and his son Philip II wanted to make the world Catholic. The events, wars, and art changed and heavily influenced the art in Latin America during the colonial period.

The Aztec and Inka were unique cultures because they prized the arts and had permanent stone architecture.

Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Aztec Empire, was conquered by Hernán Cortés of Spain in 1521. Cortés conquered the Aztecs due to alliances with other local tribes who disliked the Aztecs, Doña Marina, and diseases the indigenous population who had no immunity. Doña Marina had a facility with language and spoke the Indigenous languages of the Maya and Aztec. She also learned Spanish quickly and translated between the indigenous and European languages, helping Hernán Cortés with the Spaniard's most famous ally – the Tlaxcalans, enemies of the Aztec who helped him conquer the Aztec. In less than two years after Cortés, he defeated the Aztecs after he first saw on Tenochtitlán.

The Aztec territory became the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the namesake of Spain. Viceroyalty referred to the political unit during the colonial period. Today, we know it as Mexico City, built on top of the indigenous cultural center of the Aztec world, Tenochtitlan. The area is one of two original regions where support and money were sent during the colonial period. Cusco, the capital city of the Inka Empire, was conquered by Francisco Pizarro, known as the Viceroyalty of Peru. The region became Lima, while Cusco remained the artistic center in the colonial period. The indigenous societies of Latin America had great artistic traditions, as did Europe. What happened when these two cultures collided?

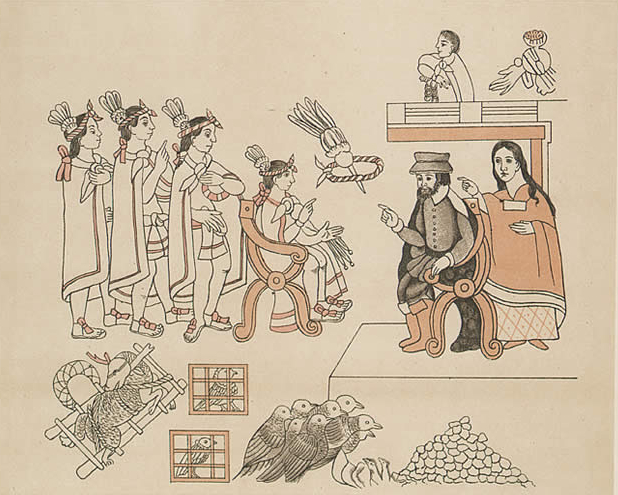

Colonial Manuscripts

Doña Marina, pivotal in the conquest due to her interpretation and translation abilities, was nicknamed La Malinche – the traitor. Although she is seen as a traitor because she aided the conquistadors in their conquest of Mesoamerica, she is also seen as an influential figure, rising from slave status to a powerful female who bore one of the first mestizos, Cortés' son. In the image Tenochtitlan, Entrance of Hernán Cortés, Cortez and La Malinche meet Moctezuma II (1.9.2), she is translating a conversation between Hernán Cortés, wearing European style clothing with Moctezuma II in his indigenous royal Aztec garb. The style of art is a complex mix of European illusionism and indigenous symbolism. The image of a building-like throne is indigenous in concept, with proportions of figures similar to those in European Renaissance art. The text itself is a mix of European and indigenous influences. Since so many Indigenous records and manuscripts were destroyed after this conquest, the post-conquest manuscripts give modern viewers a sense of life in the indigenous world.

The more than 500 post-conquest manuscripts trump the small number of pre-Hispanic codices. In the Colonial period, the Indigenous artist-scribes used European paper and bound books. The missionaries and chroniclers realized early they lost a lot of information to convert the pagan indigenous cultures to Christianity. They started to re-document the Indigenous cultures by trying to document some of the Indigenous traditions. This resulted in "mixed" style codices that incorporate both Indigenous and European influences, glyphs, and figures on the white background of the manuscripts with better proportions and Arabic and Roman text. Some texts contained both the Indigenous language of the Aztecs, Nahuatl, and European writing/language.

Historians believe The Magliabechi Codex (1.9.3) is a copy of an Aztec codex, created during colonial rule and made from European paper. The influence of the European style is visible in the Indigenous subject of human sacrifice. One of the problems with the Spanish depiction and record of human sacrifice is the number of people they claimed was sacrificed. The Indigenous groups participated in human sacrifice, and records exist in pre-Columbian manuscripts of Indigenous human sacrifice. One of the controversial aspects of human sacrifice in the Aztec Empire is the question – just how much human sacrifice occurred? The Spanish chronicled the sacrifice they witnessed. Depending on the source, some post-conquest manuscripts claimed there were 20,000 human sacrifices a year, while other chroniclers documented 40,000 human victims were sacrificed in 4 days. Although the topic of human sacrifice is controversial, it is well known the Aztecs performed human sacrifice on a much larger scale than any other culture of Mesoamerica. However, sacrificing thousands in a few days only using flint knives appears an excessive exaggeration recorded by the Spanish to hide their destructive behavior. Bloodletting and human sacrifice were intended to please the gods –sustaining the cycles of the universe and opposing forces. Although the Catholic Spaniards viewed these sacrifices as part of devil worship, they were an integral part of the Indigenous culture. The religious belief of the Aztecs was based on the need to offer human sacrifices and please their gods to have the sunrise the next day. Sun and rain supported the crops and sustained life throughout the vast empire.

.jpg?revision=1)

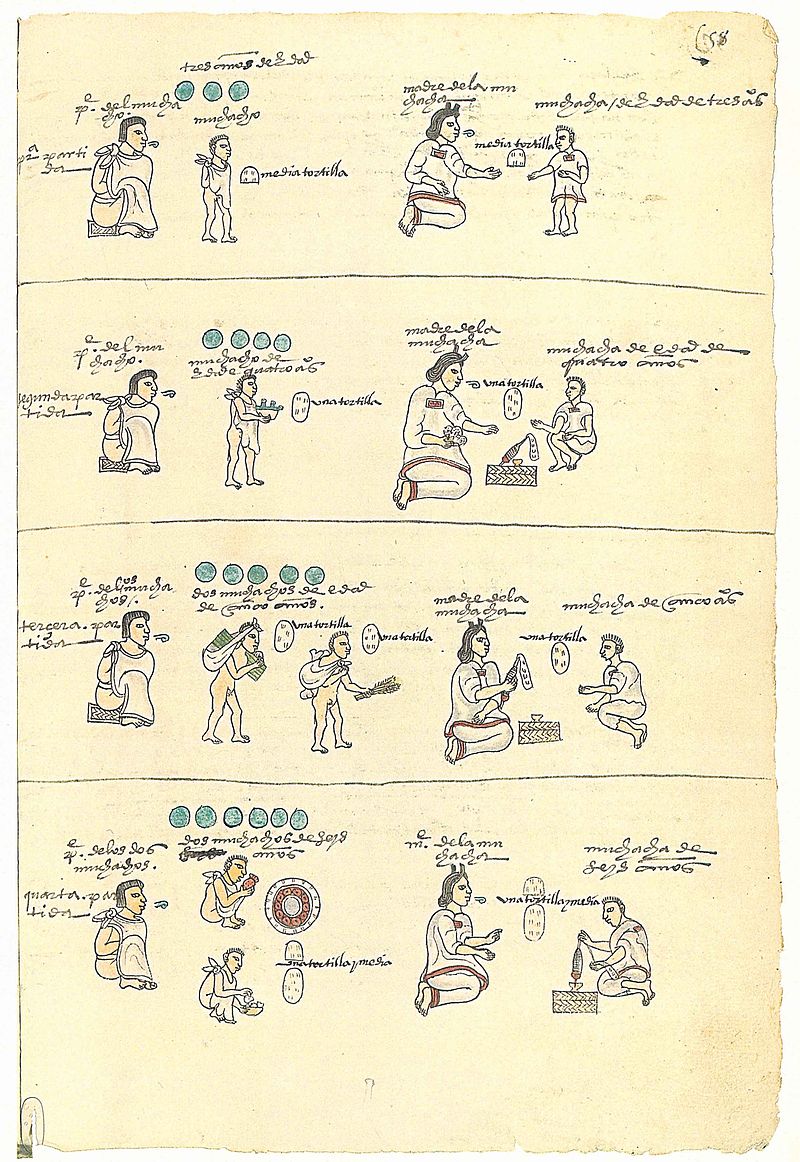

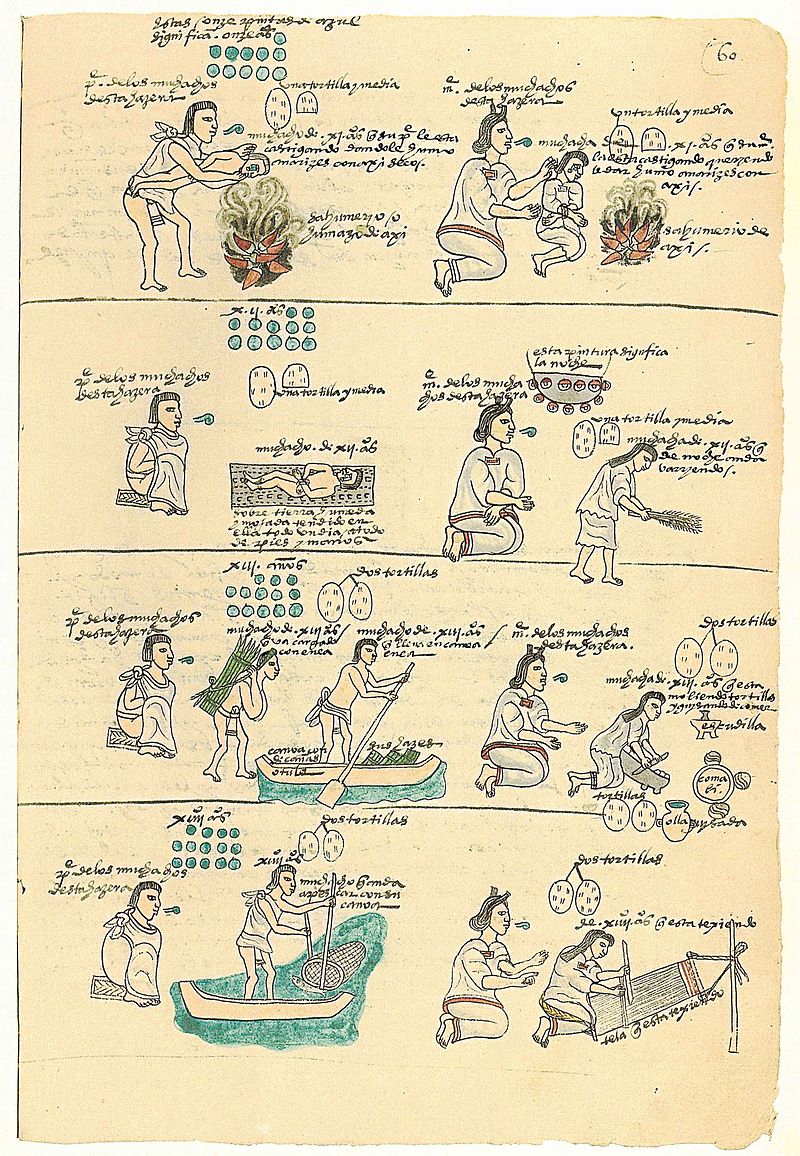

The Codex Mendoza (1.9.4) was another critical post-conquest manuscript created for Viceroy Mendoza (more realistic proportions along with Indigenous symbols) documenting everything from the history of beginning Aztec culture to scenes of everyday life. The post-conquest manuscript of the Codex Mendoza did not attempt to reconstruct the pagan religion.

The pages about raising children documented disciplines and chores assigned to children - basic everyday life (1.9.4 and 1.9.5). The figures are rendered in European style, the Indigenous influence of a blank white background still evident.

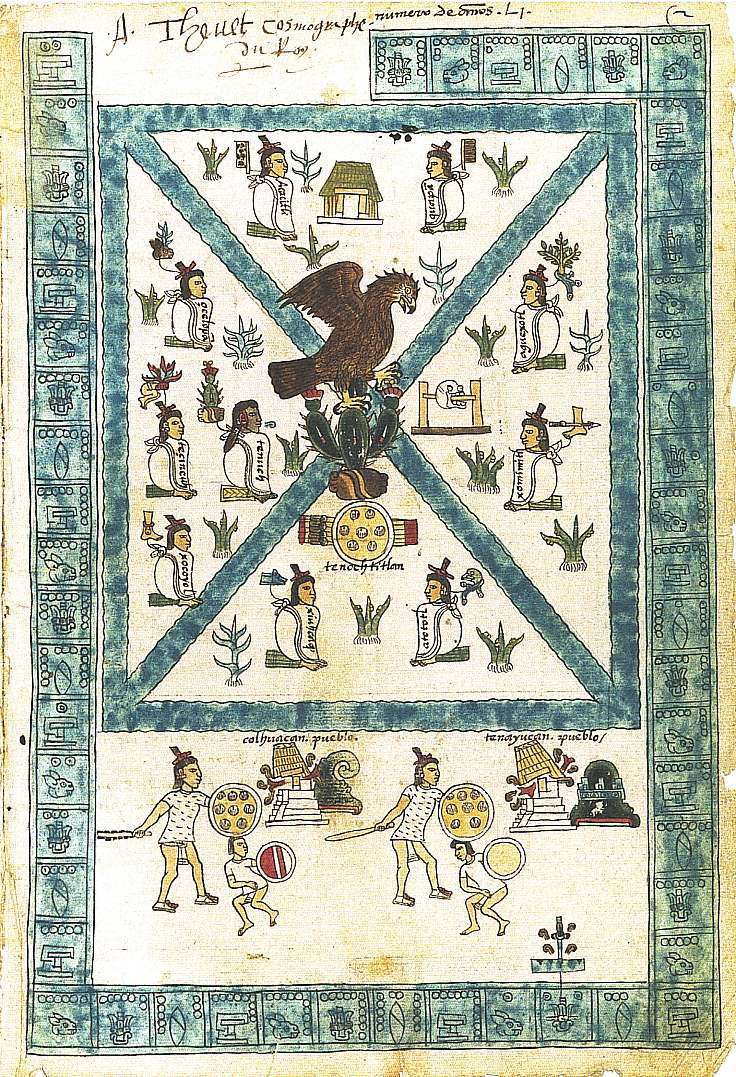

One of the most remarkable pages from the Codex Mendoza is the frontspiece, "The Founding of Tenochtitlan." (1.9.6), an eagle on the prickly pear cactus with a rock as the center – with all four corners of the world emanating from the symbol. On the frontspiece of the Codex Mendoza are battle scenes at the bottom, the four corners of the Empire of the Aztecs, and a temple at the top of the page. The temple depiction was interpreted as the Templo Mayor – or the Great Pyramid, a 39.6 meters high stepped pyramid with two temples on top. The two temples were dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlalac, the god of war and rain, respectively.

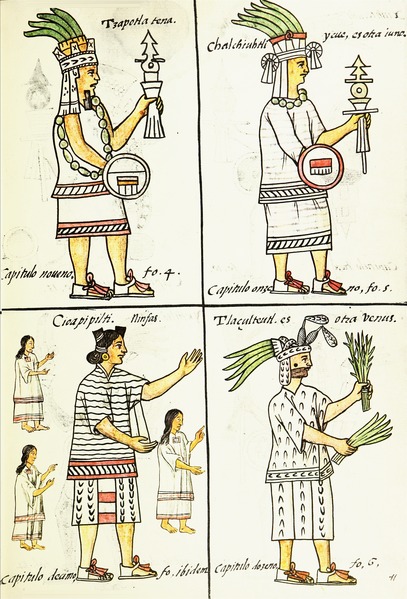

The Florentine Codex was a manuscript documenting the Aztec empire and preserving the memories of the Indigenous. Bernardino de Sahagún hired Tlacuilos (tri-lingual Indigenous artists) to illustrate and write the Florentine Codex. The manuscript page (1.9.7) documents Aztec deities, with the text, "Tlalcihuatl is the other Venus." This connection between Greco-Roman deities and Aztec deities demonstrates how there were moments in time when the Spaniards tried to connect and relate to the Aztecs by focusing on the similarities of polytheism between the great classical cultures of Europe and the Aztecs.

At first, many Indigenous traditions continued under European rule. However, missionaries sent from Spain to convert the newly discovered pagan cultures to Catholicism used Indigenous artists to help create and build a new society and create new art forms. This was a time of artistic interchange, resulting in some scientific labels describing the assimilation of art forms and cultures. Syncretism/ Convergence described what happens when two different cultures make use of a single symbol.

Early Colonial Architecture

One of the missionaries' first tasks was to document information about the Indigenous cultures and how to convert them to Christianity. Sometimes, missionaries were quite sympathetic to the Indigenous, and other times they were extremely hostile. One of the first missionaries who arrived came Europe was quite sympathetic to the Indigenous and set up a school to educate the nobles and their children. Twelve additional missionaries followed him to Mexico, documenting the Indigenous cultures and constructing churches to aid in the conversion.

The Ex Convento de San Miguel in Huejotzingo (1.9.8) reflected the new style of religious architecture, including several different cultural influences. Catholic Spain had recently been reconquered from the Moors of North Africa by Charles V, the Spanish King, and each time Spain advanced in its conquest, buildings were built with a defensive style, including battlements. The church façade is topped with battlements and gave the structure a defensive appearance, underscoring Spain's military posture in their conquest of Latin America in constructing the fortress church. Most of the stones came from nearby Indigenous structures. The elaborate and intricate designs on the stone façade are similar to the plateresques style in Spain and the bi-relief sculptures of the Indigenous.

Several other influences were common on the exterior of these early Christian churches (1.9.9) in New Spain. At the Ex-Convento de San Miguel in Huejotzingo, the side door has decorations called Alfiz – an architectural adornment of molding – usually rectangular and surrounding an arched walkway. When the Moors controlled Spain, architecture was based on Islamic-style architecture. The style was incorporated into the new buildings.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Side view of the Church of San Miguel de Huejotzingo (16th century) CC BY 3.0 - by Manuel de Corselas

Another interesting development in New World church architecture was a new form of chapels, specifically, open-air chapels. Although Europeans worshiped inside their churches, the Indigenous pagan rituals were conducted outside. When the missionaries tried to convert the Indigenous, it was easier to keep them comfortable with something familiar. They developed outside worship spaces or open-air chapels, Posas (1.9.10) (chapels) in an atrio (courtyard) – were placed in corners of a courtyard, and participants walked around and stopped at each posa for religious instruction.

In the Viceroyalty of Peru, churches were also constructed with many cultural influences; unfortunately, many early structures were destroyed by earthquakes. A 17th century church in Peru, Church in Andahuaylilas (1.9.11), is one of the most famous churches from the Colonial era in the Viceroyalty of Peru. The interior is painted in unique repetitive patterns resembling textiles.

Early Colonial Sculpture

In the center of many atrios, or courtyards of the open-air fortress churches, were stone crosses. The Cross at Acolman (1.9.12) demonstrates the complex mixing of cultures. At first, it appears like a cross; however, a face emerges from the center of the cross, while the rest of the cross is covered in foliage. The Indigenous sculptor created the cross of Christian imagery with the symbolic language of the vegetation that the Indigenous people understood. In Indigenous manuscripts, a common subject was the world tree connecting the underworld to the heavens. The cross appears to be a mix of Christian symbolism and Indigenous symbolism, an example of syncretism. If an Indigenous person looked at the cross, part of their Indigenous culture and religion with evident in the foliage. If Europeans looked at the cross, they might think the Indigenous sculptor misunderstood the actual meaning of the cross. It is still unknown if the mixing of influences was an act of defiance and deceit or acceptance and understanding by the Indigenous sculptors.

Baptismal fonts also combine European functions, for example, baptism, with Indigenous references. At the Monastery of San Miguel Zinacantepec, the baptismal font (1.9.13) has an upper border of a Franciscan cord, with an inscription in the Indigenous Nahuatl language. There are also medallions representing Christian themes, such as the Annunciation and Flight into Egypt. Between the medallions are scenes possibly representing the heavens in the Christian religion or the heavens with Indigenous birds and references to the Indigenous heavens, a connection between the Catholic religion with a functional baptismal font, and imagery recalling the Indigenous past. Sometimes, the success of translating ideas from Europe by an Indigenous sculptor was lost.

The lion fountain or feathered coyote (1.9.14) is a decorative sculpture at the Rollo demonstrating how an Indigenous sculptor interpreted, visually, a lion. The artist was asked to create a lion (the symbol of the Spanish monarchy). Because the Indigenous carver had never seen a lion, he made an animal similar to an Indigenous feathered coyote.

Early Colonial Painting

There were numerous influences to create new forms of art. However, one of the most significant influences from Europe to Latin America were simple woodcut prints and engravings. The easily portable and inexpensive art forms were used in Indigenous education, teaching the Catholic faith's religious stories.

At the Ex-Convento de San Miguel in Huejotzingo (1.9.15) are wall paintings painted by Indigenous artists in the illusionistic style of Europe, the black and white images copied directly from European prints. All the prints traveling from Europe during this period were black and white, the Indigenous painters painting what they viewed in the European prints. In Germanic and Flemish prints had decorative borders also painted by the Indigenous on church walls. It is believed the missionaries and friars of the churches supported the black and white imagery isolated from the colorful imagery of the Indigenous paintings. In the image, the Virgin Mary stands on the crescent moon below God the Father. Symbols of her purity float in the clouds beside her with important saints, who promoted the devotion of the Mary's Immaculate Conception.

There are numerous black and white images towering up the stairways at the Ex-Convent of San Nicolas de Tolentino Frescos (1.9.16). They are completed in an illusionistic style, with a sense of perspective. An interesting inclusion in this series of paintings is the Indigenous men depicted with the church's friars. Although copying imagery from Europe, the Indigenous painters seemed to have some say in the overall fresco program of the monasteries. It also demonstrates how the church officials were often lenient with the Indigenous workers.

One of the more intriguing paintings completed for a church is the murals at Ixmiquilpan (1.9.17). The series of paintings were completed on the walls down the central aisle in the church's nave. Unlike the black and white images seen at Huejotzingo, these paintings are richly colored. The subject matter is far from anything expected in a Catholic church with anthropomorphic busts. These human figures are dressed in Indigenous warrior clothing or jaguars, who battle European-inspired monsters. There is a unifying bright blue acanthus scroll flowing throughout all of the images down the nave. The acanthus scroll is standard in classical art; however, the color of the murals indicates they were not direct copies from European prints.

Additionally, Aztec knightly orders wore costumes and animal hides as painted in the paintings, not traditional European depictions. It is unknown why the church authorities allowed a battle of Indigenous figures with animal skins and weapons of the Aztecs to be painted down the main aisle of the Catholic church. Most scholars believe the Christianized Indigenous of the region painted what they knew as a representation of good and evil.

Virgin of Guadalupe

No discussion on the early colonial era of Latin America would be complete without a discussion on the Virgin of Guadalupe and her importance and an event between December 9-12, 1531, ten years after the conquest of Tenochtitlan. According to legend, a dark-skinned Virgin Mary, dressed in a blue garment dotted with stars (some scholars say the stars resemble the constellation in the skies at that time), appeared to a Christianized Indigenous man named Juan Diego. He was just north of Mexico City on the site of an old Indigenous temple to the Goddess Tonantzin, "Mother of the people." The Virgin spoke to him in the Indigenous Aztec language, Nahuatl, and asked Juan Diego to approach the bishop to build a church in her honor at this location. Unfortunately, the bishop did not believe Juan Diego. Juan Diego attempted to go over the hill again to meet his sick uncle, and the Virgin appeared to him again. He explained the bishop did not believe him. After the third attempt, he explained that the bishop wanted evidence. On December 12th, the Virgin Mary told Juan Diego to gather roses from a rose bush, not blooming in the winter or the rocky terrain, and to bring the roses to the bishop as a sign. When Diego opened his cloak (1.9.18) to show the bishop the flowers he gathered, the miraculous image of the Virgin of Guadalupe appeared on his cactus fiber tilma (cloak). It is believed the original cactus fiber tilma is on view during the Virgin of Guadalupe's feast days in December each year, even though the cactus fiber cloak should have disintegrated after 20 years, even surviving a bomb attack in 1921. Although some question the authenticity of the religious relic, far more people have complete faith and devotion in the Virgin of Guadalupe.

The first painted reproduction of the Virgin of Guadalupe, called a Guadalupana, was in 1606 by the Spanish immigrant Baltasar de Echave Orio. From this point forward, every time an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe was created, it was made following the exact depiction found on the cactus fiber tilma relic in the Basilica of Guadalupe. Except for the medium or skill, the image presents the dark-skinned Virgin in a red dress and blue mantel covered with stars, standing in front of a ray of light, her head bowed. A bow is tied around her waist, and she stands on a crescent moon supported by an angel.

In the immediate years after the Spanish conquest of the New World, social, historical, and artistic changes in the Viceroyalty of New Spain and the Viceroyalty of Peru were unprecedented. The powerful influence and control of the Catholic church and Spanish government changed the cultural and religious environment of the people. Using black and white prints from Europe, Indigenous artists created new and different architecture and art under the direction of the new conquerors while still incorporating local traditions.