6.18: Aztecs (14th – 16th)

- Page ID

- 31844

The Aztecs dominated from the 14th to the 16th centuries inhabiting Tenochtitlan and two other associated city-states. At its pinnacle, the Aztecs had a rich and complex cultural environment located in present-day Mexico, the swampy land of the area transformed into a large complex with a pyramid temple similar in size to the great pyramids in Giza. The society was divided between nobility, commoners, and the gods Tezcatlipoca, Tlaloc, and Quetzalcoatl and the support structures for the gods. About 20% of the population cultivated and provided the food for the Aztec Empire, while 80% of the population was traders, artisans, and warriors. Work from the artisans became an essential part of a source of income for the Aztecs.

Tenochtitlan was built on the modern-day site of Mexico City, based on a symmetrical layout dividing the city into four sections with the Great Pyramid as the centerpiece. Houses were made of wood and clay with woven reeds for the roof while the temples and palaces were constructed of stone. They built canal systems rivaling Venice, Italy, to irrigate the terraced areas of farming, in swampy areas they raised the land and separated areas with small canals. Connecting causeways to the main island, built by driving pylons into the wet marshy land and covered with stone and rock, provided travel capability on foot.

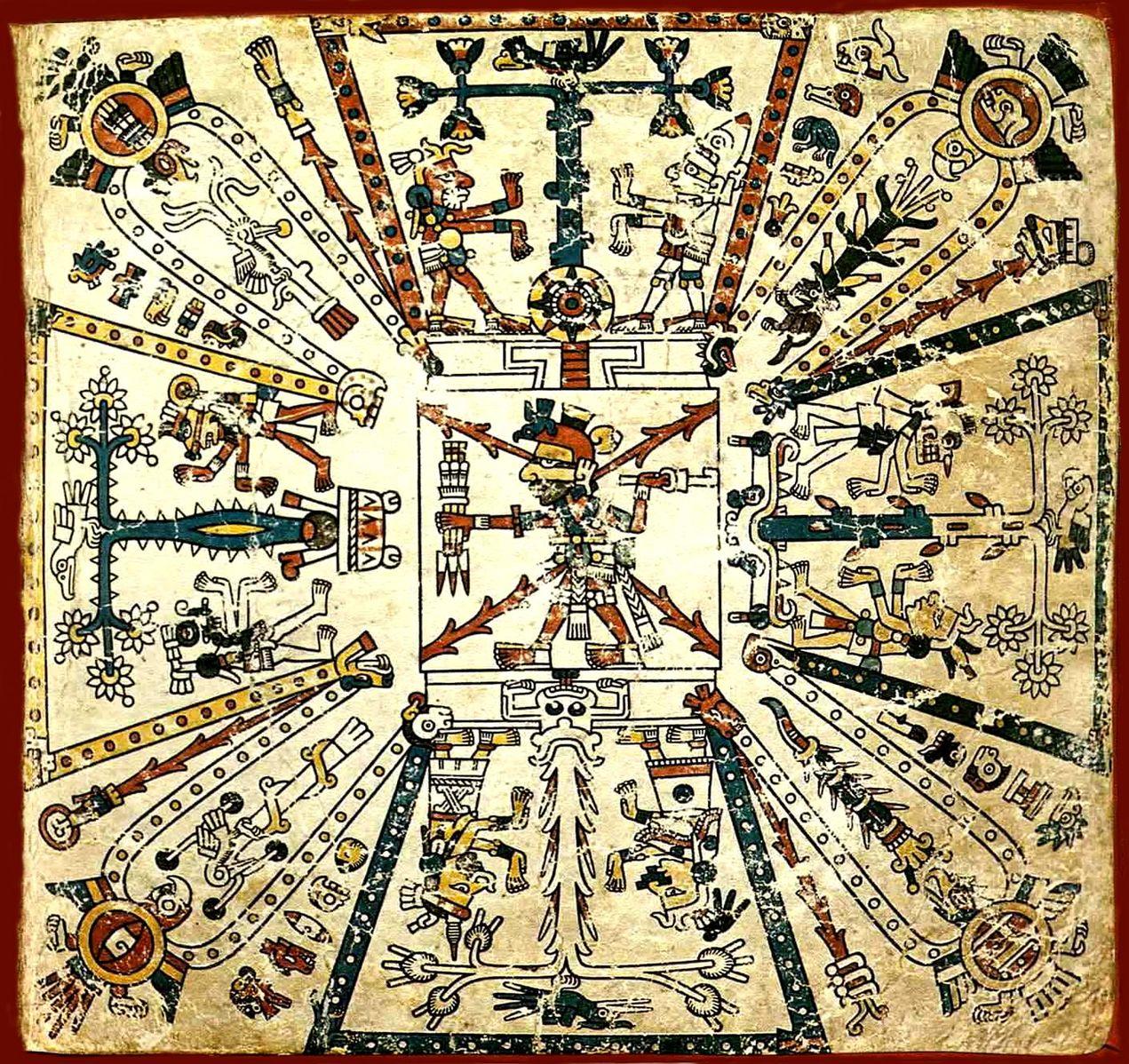

Songs, music, and poetry were highly esteemed in the Aztec empire and supported the arts with contests and performances by actors, acrobats, and musicians. Poetry and the words had multiple meanings that supported war and the gods alongside natural objects like flowers. Many of these poems still exist today, and although the Aztecs did not have a complete writing system, they did use logograms. The drawing (6.86) represents the lord of fire standing in the center; logograms of the cosmos are portrayed around the center.

Metalwork was a specific focus of the Aztecs using gold and silver to create rings, earrings, pendants, and necklaces, all decorated with eagles and tortoiseshells made by lost-wax casting and delicate filigree work. Unfortunately, very little survives today because the Spanish gathered up all of the precious metal and melted it down to carry back to Spain. Stone sculptures did survive and were replicas of one of the many gods the Aztecs worshipped. The sculptures would be seated, standing, or in other positions, a few of them had a hollow space carved in the chest of the sculpture to hold the heart of a sacrificed victim. Many of these sculptures were painted with bright colors, although the paint faded with time. Small sculptures were made in the form of local deities, especially agriculture deities (6.87). Turquoise rock was used to make mosaics to cover masks or sculptures, snakes were a common theme and used as a motif for artwork. Made from carved wood, the two-headed snake (6.88) was covered with turquoise, pieces of a shell for embellishments.

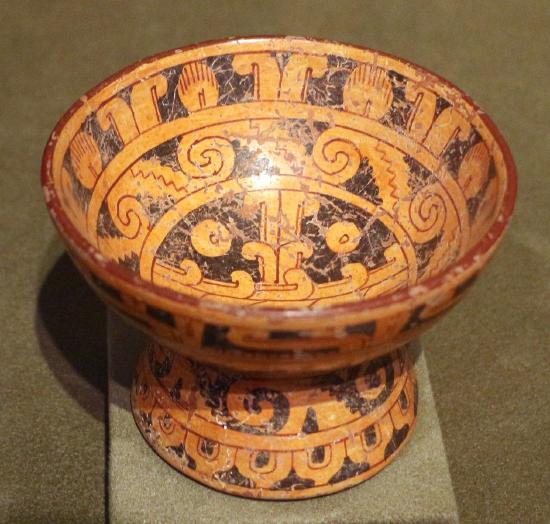

Miniature work was created with themes of plants, shells, birds, or any natural entity. They used jade, a highly valued mineral, and feathers from the quetzal bird and other birds cut up for decoration. Feathers were cut into fragments and glued to a strong feather base. Small layers of natural feathers were applied first then covered with more ornamental feathers with glue made from orchid bulbs. Feather artwork seldom survived, the feather shield (6.89) is one of the pieces existing today. Even though they did not use a potter’s wheel, the Aztecs made sophisticated pottery (6.90) with legs or spouts, handles, or unusual shapes. The vessels were created in the coil pot fashion with thin-walls and covered with red, black, or cream slip; polychrome ceramics had designs painted with black or brown. They also added exotic motifs of animals, plants, or geometric shapes.

Standing 2.7 meters high, the basalt statue of Coatlicue or the “Serpent Skirt’ (6.91) is generally considered the best example of Aztec sculpture. The statue of a goddess with two snakeheads, wears a skirt of snakes, a necklace made from dismembered body parts, human heart pendant, and clawed hands and feet. She a major Aztec figure and considered the earth-mother goddess and thought of as a fearful figure.

The Sun Stone (6.92) is one of the most recognizable pieces of Aztec art. The basalt stone measures almost four meters in diameter and is about one meter in width and represents the Aztec myths of the five worlds of the sun. The center of the stone has a relief carving of the sun god, Tonatiuh or the night sun, Yohualtonatiuh, all surrounded by other critical symbolic images.

The Aztec Empire swelled to 15 million people and when cultural hegemony control waned, so did the great empire of the Aztecs. Climate change, warfare, and the invasion by Cortes in 1521 lead to the fall of the Aztec Civilization.